Early Explorations In Ingleborough Cave, Clapham

By J. A. Green

The following correspondence resulting from the paper on Ingleborough Cave, Clapham, printed in the Journal (1901 Vol. 1, No. 3 page 220-228), calls for an equal amount of publicity. From its perusal not the slightest doubt remains in my mind that the place which my companions and I named the Canal had been previously visited by two parties at least, and I desire that our unconscious egotism in assuming that we were the first shall be, so far as it may, atoned for by a ready acknowledgment of the prior visits of Mr. James Farrer so long ago as 1837 and 1838, and of Prof. Hughes in 1872 or 1873.

It is regrettable that the arrangement of the correspondence and this acknowledgment were not prepared in time for inclusion in number 4 of the Journal, but a long illness which rendered me incapable of doing this will perhaps be accepted as a sufficient reason.

The correspondence taken in order explains itself.

GIGGLESWICK SCHOOL,

NEAR SETTLE,

16th April,1901.

To

J. A. GREEN. Esq.

DEAR SIR.

I have been reading with interest your account of the Ingleborough Cave.

You, in turn, may be interested to hear that a similar exploration was made a good many years ago by the late Mr. John Birkbeck, Junr., Prof. T. Hughes, Mr. Tiddeman, myself and others. I don’t remember the date, but it was not very long after-the great storm which changed so considerably the far end of the cave.

At that time what you call the Cellar Gallery was fairly dry and could be managed, though not very comfortably, by ladies.

The Giant’s Hall was easy of access; we searched in vain for other exits besides the one you used, but we found your slit of some six inches high more convenient than it was when you were there. We had to crawl a considerable distance and then came to the water. After trying other ways we took to the water and followed it until it deepened and narrowed, and until the roof came down nearly to the water itself.

Four of us were roped and I think the man who went furthest was in the water up to his shoulders.

Prof. Hughes would be interested to see your account, and he would, no doubt, be able to give you a more particular account of our expedition,

He published somewhere or other an account of the great flood to which I have referred.[1]

You refer to the swimming of Mr. Farrer. If I remember rightly Mr. James Farrer told me that this happened not very far from the mouth of the cave, beyond the barrier now cut through.

I once tried going up the stream that issues close to the cave. We could not get very far; the roof came down to the water.

Most faithfully yours

G. STYLE.

21, BRUDENELL GROVE,

LEEDS, 15 th May, 1901.

To the REV. G. STYLE,

Giggleswick.

DEAR SIR,

I was pleased to receive your most interesting letter of the 16th ultimo.

It would certainly appear from the general description, that your party reached the point at which we were stopped. The one thing which strikes me as being strange is that you do not mention the remarkable characteristics of the water channel, which I think could not fail to strike any one entering it – perfectly straight and uniform in breadth, and with an arched roof of marked regularity. Did you notice this?

I think also that it might be possible to wade along the channel if the water was very low. A second journey which I made on the raft, equipped with a primitive apparatus of string and stone for taking soundings, resulted in my finding no greater depth than about seven feet, and, while I am not prepared to say that it is nowhere deeper, I do not think it can be. The average depth was about six feet, so far as I could judge roughly.

You do not say anything about our passage to the left – the dry and very low one. Did you see it?

The Editor of our Journal, Mr. Gray, who was of the party, suggests that the pool in what is now known as the Cellar Gallery may easily have been caused by a dam being formed by the silting up which has altered the level of the floor of Giant’s Hall, and that the drippings from the roof in the gallery would keep a supply of water in such a place.

For my part, I am of opinion that this part of the cave is frequently under water. Each time I have been in it there have been horizontal lines of foam on the walls at varying heights.

If you are right about Mr. Farrer’s exploit having taken place not very far from the cave mouth, then Prof. Phillips in his “Rivers, Mountains and Sea Coast of Yorkshire,” pp. 31 and 32 must be wrong. I should like to get to the bottom of all this. If you can tell me anything more I shall be glad.

It would be well if we could clear up some of these old tangles and place on record a correct account of the various happenings in the exploration of this cave.

With thanks for your most interesting letter.

I am, very faithfully yours,

J. A. GREEN.

To which Mr. Style replied as follows:-

GIGGLESWICK SCHOOL,

NEAR SETTLE,

17th May, 1901

J.A. GREEN, ESQ.

DEAR SIR,

Prof. T. McK. Hughes, F.R.S., Clare College, Cambridge, will I have no doubt, be able to give you a better account of the features of the furthest passage in the cave, than I can.

I have had a conversation to-day with Mr. Farrer, the present owner of Ingleborough, who throws some doubt upon the authenticity of the stories that are told about the early visits to the cave; he tells me however that his uncle Mr. James Farrer, who took very great interest in the early exploration of that, and other caves, has left in manuscript records of what was done, and Mr. Farrer intends to try and find these records.

If you get an account from Prof. Hughes, you may very reasonably pass over my incomplete notes of our scramble.

Most faithfully yours,

G. STYLE.

21, BRUDENELL GROVE,

LEEDS, May 23rd, 1901.

PROF. T. McK. HUGHES,

Clare College, Cambridge.

DEAR SIR,

I enclose for your acceptance a copy of No. 3 of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club Journal. It contains an article by myself on some exploration in Ingleborough Cave, Clapham, which was done by a party of which I was a member. Further, I am sending for your perusal copies of some correspondence which has been evoked by my paper.

If you will be so good as to verify, correct or extend Mr. Style’s remarks, I shall feel indebted to you. To those of us who have spent much time in the exploration of the caves and pot-holes of Craven, it has been a matter of regret that the early work has in many cases found no permanent record. So far as we knew, up to the time of receiving Mr. Style’s letter, we were the first to have passed Giant’s Hall bent on serious exploration. This not being so, it is my wish to accredit those gentlemen who preceded us, and if at the same time new facts of interest can be traced and added so much the better.

I hope later to obtain from Mr. Farrer the MSS. which Mr. Style speaks of. They are bound to be of great interest and it is sincerely to be hoped that they are still in existence.

I am, dear Sir,

Faithfully yours,

J A, GREEN.

To this Prof. Hughes replied so fully and added so much that is of interest to cave explorers generally, that in itself it forms an able disquisition on the formation of caves, and is therefore printed verbatim.

18, HILLS ROAD,

CAMBRIDGE,

October 29th, I901.

J. A. GREEN, ESQ.

DEAR SIR,

I forward herewith some notes on the far part of Ingleborough Cave. I have tried to get more exact information respecting the date, &c., of our early exploration, but without success. If I can assist you any further, pray command my services

Yours very faithfully,

T. McKENNY HUGHES.

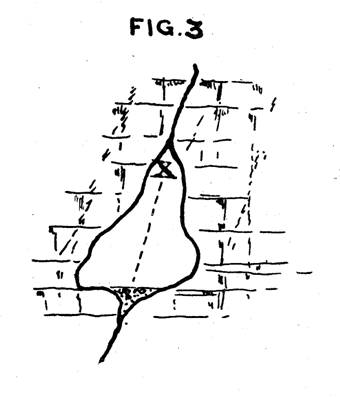

“I cannot give the exact date of the early exploration of Ingleborough in which I took part, but it must have been before the great thunderstorm of July, 1872,[2] a description of which I published in 1887.[3] The cave was so altered by that flood that I believe it has never since been possible to reach all the parts beyond the Giant’s Hall which we then explored.

As we meant then to make only a preliminary examination in order to learn whether there was any considerable cave that could be explored beyond the Giant’s Hall, and intended to return and carry out a more systematic survey later on, we kept no exact record of the directions or the distances traversed.

We were two hours walking, wading, and crawling under ground through new passages, and, therefore, the effort to remember the way out again did impress the turns and general direction upon our minds. I have here endeavoured to indicate by a sketch the impression left upon my memory of the part we then explored, based upon a plan of the old cave drawn by Mr. Farrer.

There are two kinds of cave well developed, perhaps we may say about equally well developed, in the under ground water courses of Ingleborough; namely the bedding caves and the fissure caves, with of course all combinations of the two, and, for the sake of easy reference, I will shortly explain what I mean.

In the bedding caves the water finds its way along the nearly horizontal divisional planes due to the original stratification. The exact horizon where these have been opened out have been determined by many accidents. For instance, the occurrence of a band of more impervious rock such as shale, or of less soluble rock such as dolomitized limestone, or it may be the knobbly faces of some contiguous beds caused by concretionary action, or the manner of delivery of the water supply on to the bedding face and so forth.

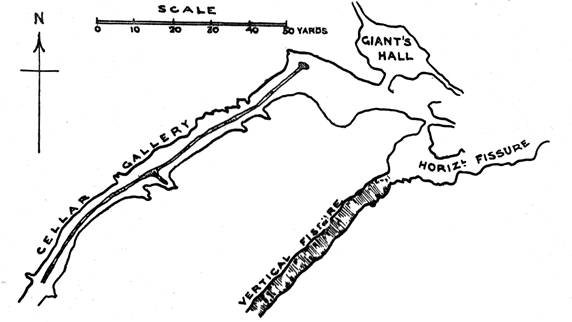

Whatever may have been the combination of circumstances which determined them, a very common feature is an irregular lenticular opening coinciding in general direction with the bedding of the rock as shown in Fig. 1.

Of course where an unsupported roof is extended too far by the slow lateral work of the water it will sag and touch the floor or break down, while sometimes the fallen masses, travelling on, will be wedged under it in narrower openings and act like props or walls in a mine.

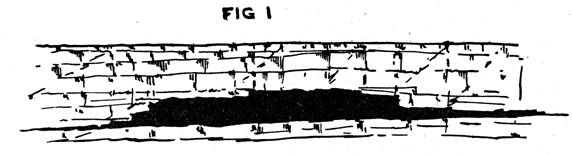

The other common and simple form of cave is that due to faults or master joints. In this case the cave has usually a greater height than width — see Fig. 2. It is apt to thin off into an Ogee arch above, as shown at X. in Fig. 3, and owing to the action of the water being more frequent and continuing longer on the lower part, the cave not uncommonly has a pear-shaped section with broader end down, as also in Fig. 3.

When a fissure-cave tapering downwards is clean swept it is very difficult to get along it, because ones body, knees, and feet get stuck between the converging sides; but it often happens that a great mass of debris is jammed in the narrowing fissure and provides a rough but safe path.

The intersection of more or less vertical fissures with nearly horizontal lines of weakness along bedding planes, see Fig. 4, gives rise to innumerable varieties of form and is generally the explanation of large chambers and sudden expansions.

All of these forms and many different results of combinations of them with various conditions affecting the feeders, outfall, etc., are met with in Ingleborough cave, and it will facilitate reference and save repetition to have drawn attention to them.

The lower cave where the water now usually issues and the “Second Creeping Place” in the upper cave are good examples of the bedding cave illustrated in Fig.1, which, as we shall see immediately, is well illustrated in the new part of the cave explored by us. The upper cave near its mouth is also of the same character but it communicates at once with a series of fissure-caves or caves of mixed character, every variety of which may be seen before we get to the Giant’s Hall, which is the end for most explorers. The parallelism between the fissures transverse to the general trend of the cave should be noticed as they offer a suggestion as to the probable direction of openings which may be useful in future explorations further in. It will be observed that the “Stalagmite Gallery,” the “First Gothic Arch,” several other arches between that and the “Second Gothic Arch,” and the “Second Gothic Arch” itself are all approximately parallel and indicate an important system of master joints and fissures.

We were not able exactly to identify any of these with the cross fissures in the long water gallery.

The party consisted of Mr. John Birkbeck, Rev. W. Mariner, Rev. E.T.S. Carr, Mr. Tiddeman, Rev. G. Style and myself and, having rapidly traversed the old cave, we descended to a lower level at the South East corner of the Giant’s Hall. Bearing away first to the left, we found that this part of the cave belonged entirely to the bedding-cave group, Fig. 1. We crept for a considerable distance through broad but very low passages; indeed we found the roof and floor often approached one another so closely that it was only by squeezing our way through in contact with both that we could get on at all. Sometimes there was a good deal of sand which we were able to push aside with our hands and feet and so press forward.

There were many similar lateral openings so that we felt that we must be careful to observe, and leave marks along our route with a view to our return. Along the line where we advanced farthest the roof and floor got nearer and nearer together until our progress was quite barred, but we saw several directions in which it seemed possible that a little digging might open a passage.

We then returned, keeping as close as we could to the left, until we came to a deep fissure running as we thought towards the mouth of the cave. Along this, although it was somewhat rough, we travelled easily for a time, which was due, as well as I can remember, to its being filled with boulders and sand. By-and-bye however the fissure-cave was more clear of debris and we could see that it tapered downwards. It was then so full of water that we could not find the bottom, but Mr. John Birkbeck swam and climbed a long way beyond the rest of the party. The water was moving slowly in the direction in which we were going i.e., as we thought, towards the mouth of the cave. We were about two hours in these passages, but suffered more from the coldness of the water than from anything else.

The two types of cave which I have distinguished above were well exemplified. When we turned to the left after descending to the lower level from the Giant’s Hall, we travelled entirely under the low flat roof of a cave belonging to the first type, but when we turned back and followed it to the right we came into a long cave of the second type. Experience tells us that in that district the caves of the second type carry us much further than those of the first type, and therefore are better worth opening up and following.

Large caves of the first type however generally indicate strong feeders of the second type, and a careful record of the exact position of each would probably lend much help to those who propose to explore the under ground water courses of Ingleborough.”

As it appeared possible that Mr. Farrer could throw some light on the exploration made by his uncle in 1837 and 1838 he was approached, and the following interesting communication was received from him :-

INGLEBOROUGH,

LANCASTER,

April 23rd, 1902.

DEAR SIR,

Your letter interested me much.

As my uncle’s explorations occurred in the years 1837 and 1898, neither Mr. Style nor Prof. Hughes can have been with him at the time.

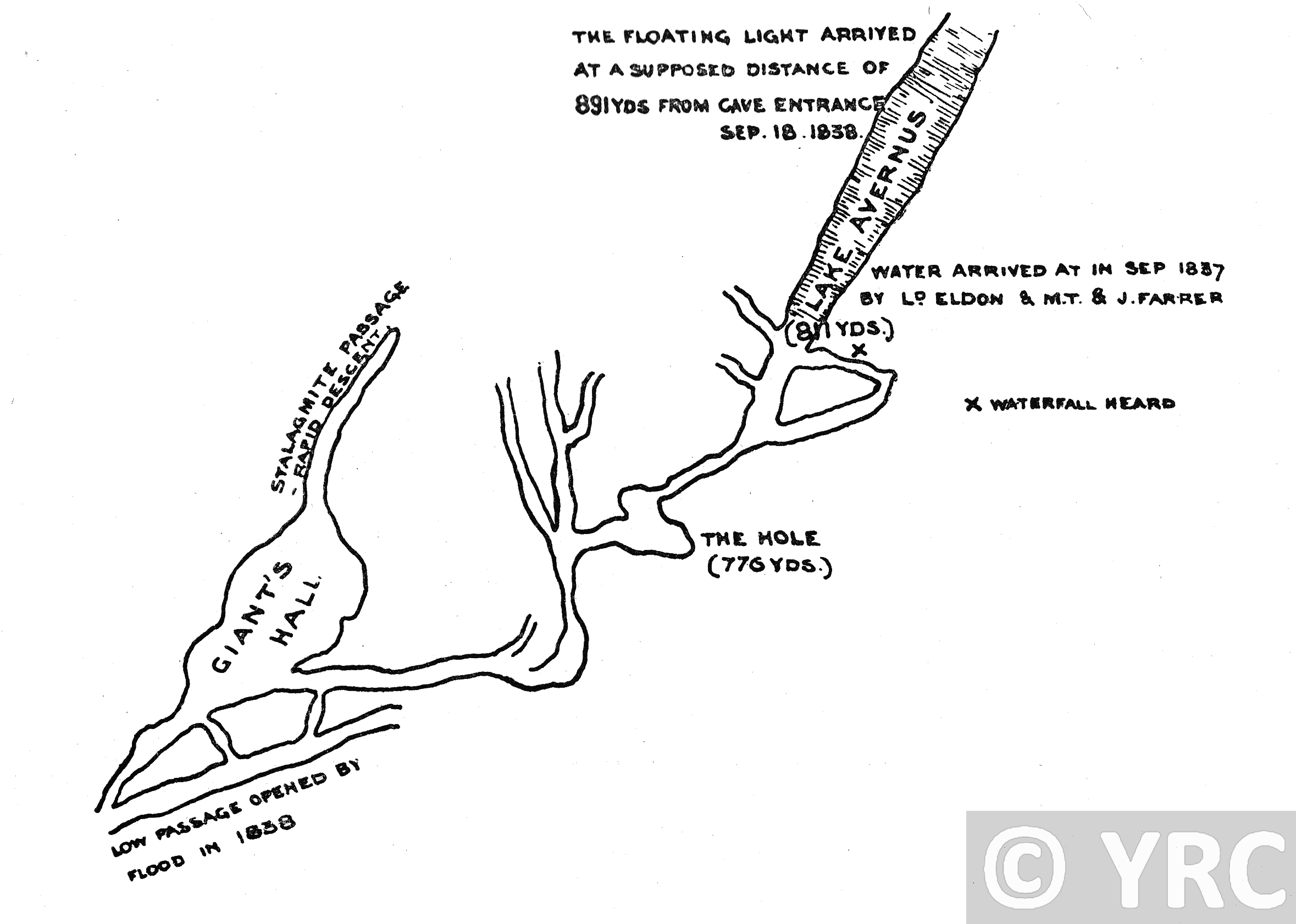

But Mr. Style is right about my uncle having left a written description of the cave as first discovered. It is inserted in his own handwriting in a book kept by my grandfather called ‘the Cave Book’. It fills about 3 pages. It contains no direct allusion to swimming, but references to variations of depth at different places are suggestive of swimming. For instance, at about 910 yards from the creeping place he alludes to a passage turning to the left with a sudden descent, at the bottom of which the passage continues in a straight line for about 40 yards when it becomes “so low with such depth of water as at present to defy further progress.”

This place (wherever it is) I think he may have tested by swimming. For my grandfather’s journal for October 11th, 1837, referring to that day’s exploration, says of my uncle and father and two others: “they prosecuted their discovery till they were stopped by a depth of water, which James (my uncle) fastened by a rope tried to fathom, but it was too deep and he regained his party safe.”

This does not look as if the swimming on that occasion amounted to much. My grandfather was himself in the cave that day, but appears to have kept behind the others. A note by Lord Encombe (my uncle’s half-brother) referring to the same day says: “James, M. T. Farrer, and Encombe, accompanied by Wm. Hindley passed through the shallow water-fall and reached the deep water at the distance (supposed) of 940 yards from the entrance gate. Here James swam with a rope attached.” I have often heard my father refer to the same event, and I think it proves that my uncle did swim somewhere on that day, but from my grandfather’s account I should doubt if on that day the swimming was long continued.

As to what point this refers to I am in ignorance, but there is in the same book a plan of the cave made by my uncle of which I enclose a rough copy. It appears, I think to show that it was somewhere beyond the Giant’s Hall.

The distances are stated to have been ascertained “by lengths of balls of twine used as guides for returning.”

So much for the year 1837, that of the cave’s discovery. Now for 1838. Prof. Sedgwick (see his Life v. 1, p. 519) refers to a visit he paid my grandfather in October of that year, when they went to the cave. “We endeavoured (at the distance of about three-quarters of a mile from the entrance of the cave) to make some new advances …. we wriggled our way about 200 yards when the roof became more lofty and the water more deep. We were provided with a cork jacket, &c. We sat on a low ledge of rock …… l and solaced ourselves with a cigar, a luxury our floating friend could not enjoy while he held a large candle in his mouth to light his way over the waters. After running out 100 yards of rope the chamber closed, and the water seemed to escape through many narrow sink-holes. So the voyager came back, and we all returned as we could, &c., &c. (October 5th, 1838.)”

My grandfather’s account of Sedgwick’s visit fixes the date to October 5th. “After breakfast we all went to the cave with our guest Sedgwick.” The party lunched in the Giant’s Hall, and when the ladies returned home after luncheon James and Matt (i.e. my uncle and father) led Sedgwick down below the Giant’s Hall. . . The result is that Sedgwick and the rest were satisfied that no other caves are within reach on that side.” The swimming on this occasion, vouched for by Sedgwick, but not mentioned by my grandfather, must, I think, have been done by my uncle, and at a point apparently some way beyond the Giant’s Hall; since the distance of the latter is given as 702 yards, whilst the plan speaks of 891 yards for the further point.

My uncle was of course frequently in the cave, and may have swum about on several unrecorded occasions. I certainly gather that he did so when Sedgwick was there. It is odd that you should have written to me just now, as I only chanced on the passage in Sedgwick’s “Life” last Sunday.

I notice that Mr. Green, on p. 224, [Club Journal, Vol. 1 No. 3] speaks of a place where apparently the party might have swum, and would have swum if they had had ropes with them: possibly this is where my uncle did swim.

As his plan was clearly made in 1838, and bears special reference to explorations made on September 4th and 5th of that year; and as his written description seems to be explanatory of the plan, I should say the latter was written in 1838, and that on those occasions also he may have done some swimming, before the occasion related by Sedgwick.

Perhaps I had better quote his own words for what they may be worth. I start from an allusion to the long Gothic arch, which I think means the Giant’s Hall. “This part of the cave is rather narrower, and is most beautifully inlaid with stalactites of different forms and sizes, and finally, after about 30 or 40 yards, terminates in a low narrow point where the arch has evidently been blocked up by stones and sand and accumulated stalagmite. The supposed distance from the small pillar to which the string is attached is about 910 yards–(he first wrote 310, and then seems to have changed the 3 into a 9, which makes a difference.) The passage which turns to the left now becomes very narrow, and the descent very sudden; on reaching the bottom, the passage continues in a straight line for about 40 yards, at which point one end of the line of string terminates; it is here so low with such depth of water as at present to defy further progress. Returning therefore about 40 yards, the cavern turns to the right which leads to a small but deep round hole (marked on plan) sufficiently high to admit of standing upright. Proceeding to the left again the passage becomes very low, and the water the current of which becomes much stronger, is of a dark colour, and has every appearance of having passed over the fell. Near this part another passage leads to the left, still very low with but little water. This passage remains yet unexplored; in some places the bed of the stream passes over solid rock, in others stones and sand intermingled form the course over which the stream flows. Here the noise of rushing stream becomes much louder and after creeping about 30 yards further we enter a high but narrow passage, probably about 4 feet in width, into which the water falls; the water which is very rapid near the point where the stream joins the still water, is within a distance of nine yards very deep; the cavern is supposed to turn to the right, but nothing is known further at present owing to the depth of water. There is no under-current; the stream rather turns to the right, and the water almost immediately becomes very deep. There is here neither stalactite nor stalagmite, nor is there apparently any lower level of water. The distance to this deep pool of water from the commencement of the descent is supposed to be about 150 yards, but owing to the numerous turns and passages this calculation is obviously very uncertain.”

I don’t know how far this can be made to tally with the Ramblers’ explorations on the same spot, but I should think that the great storm of 1872 might, to some extent, have altered the configuration of this portion of the cave, as it affected other parts.

Yours sincerely,

J. A, FARRER.

As I said before, it seems quite certain from the foregoing correspondence that two parties at least reached the Canal (or Lake Avernus as they termed it) before our party. The sketch plans of Mr. Farrer, Prof. Hughes, and one made by our own party do not differ much in their main features, but in the direction in which the Canal is placed and its distance from the Giant’s Hall there is much difference. This is just what one would expect from the very winding route followed. It is regrettable that we made no careful survey; but the fact that these most uncomfortable passages ended so disappointingly rather quenched our ardour. We still hope to go over the ground more carefully, and with compass and line.

The main feature of difference in the condition of the cave is the silting up of the Giant’s Hall entrances. At the time of our visit it was only with great difficulty that we could force passages into and out of it owing to the packing of sandy debris which filled up the approaches.[4] Prof. Hughes simply remarks: “we descended to a lower level,” which would indicate that at that time the difficulties were much less than at the time of our visit.

As a last word I would say that the pleasures of our work were as great as though we were really, as we supposed ourselves to be, on unexplored ground, but this does not cause us any the less willingly to give up the honour of the pioneer work to Mr. Farrer in 1837 and 1838, and to Prof. Hughes in 1872 or 1873.