The South East Arête Of The Nesthorn

By Geo. T. Lowe.

(Read before the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club, November 27th, 1906.)

The summer of the year 1895 was nearly run and late in August I was still without any definite plans for my annual holiday. Just when I had begun to think seriously about the question a letter from Slingsby, like ” a bolt from the b1ue,” settled the matter for me. “Would I like to join him to meet the Hopkinsons at the Belalp for some easy climbing ?”

Of course I liked, but felt doubtful about the “easy” as applied to climbing by our President. I joined Slingsby in London on Thursday, the 29th of August, and next morning we travelled straight through to Brieg, in the most delightfully clear weather. With a little difficulty we hired a porter and mule to carry our luggage to the inn on the Belalp, and arrived there very sleepy at 11 o’clock on Saturday night.

Next morning found us much fresher and at breakfast I met the late Dr. John Hopkinson and his family and two brothers, Dr. Edward Hopkinson and Mr. Edwin Hopkinson. The awe-inspiring feeling which one experiences in “the presence of great amateurs who climb without guides soon passed away and I felt relieved. I had been worked up to a high pitch of excitement on the outward journey by our jovial and ever youthful President who never sets out to the Lake District, Norway or other climbing playground without a nice little climb or two up his sleeve, which only requires doing, the Dent du Requin, or Mouse Ghyll, to wit. The “doing ” may be severe and so you’ll find ; but you’ll arrive all the same.

I will not dwell on the few days we spent on various expeditions, including the first traverse of one of the many Rothhorns, the culminating point of the Fusshörner ridge, from the Triest Glacier to the Oberaletsch Glacier. From the Rothhorn the Fusshörner looked wicked enough to dismay the most enthusiastic rock-climber ; but on Friday, September the 6th, Messrs. J., E., B., and J. G. Hopkinson made the first ascent of the middle point.[1] The steep western ridge of the Rothhorn was a most exciting climb, terminating in a chimney by which we gained the glacier, more like the Great Chimney on Almescliffe than anything I have seen in the Alps. Slingsby was lucky enough to find a fine crystal, a fitting souvenir of the climb.

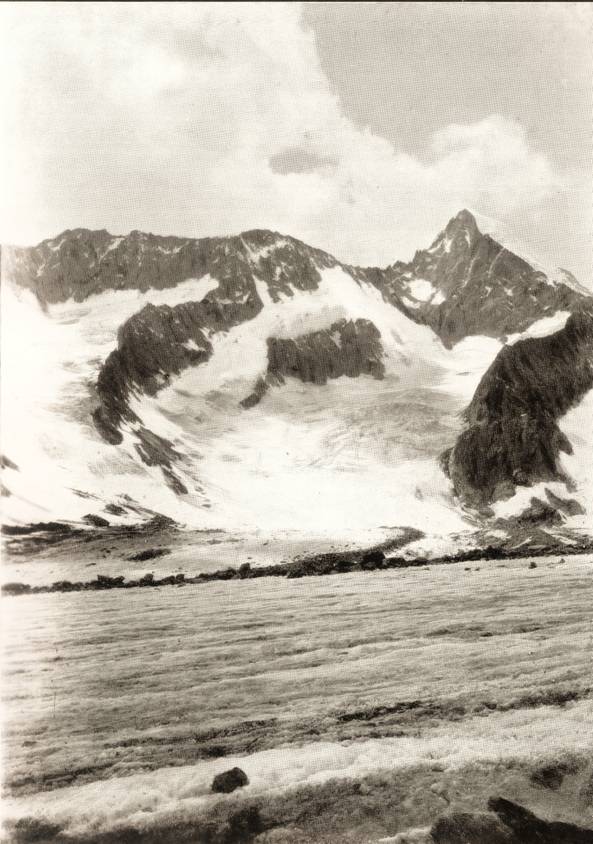

On Wednesday, the 4th of September, we were up at 3 o’clock, and at 4-25, in the chilly darkness the Hopkinsons, Slingsby and I, with a local porter, descended the rocky path round the foot of the Sparrhorn on to the Oberaletsch Glacier. A little before we reached the ice the shrill whistle of a marmot attracted our attention, but in the morning mist it was impossible to catch sight of the little animal. For the same cause we were not able to enjoy the magic effect of the sunrise on the mighty peaks, the most delightful and entrancing effect a lover of the Alps can experience. Soon the air cleared and bright warm weather favoured us as we began to move up the almost uncrevassed glacier, which provided very easy walking over comparatively level ice, broken by small pits and narrow channels for the most part like the limestone terraces of our Craven Highlands. As we advanced towards the Nesthorn at the S.W. corner of the valley the surface became more rugged and broken and frequent moulins suggested the pot-holes of our Yorkshire fells. On the right the broken ridge of the Fusshörner, then almost unclimbed, stretched like a huge wall guarding the north,[2] and on the south the jagged ridge extending from the Unterbachhorn to the Nesthorn seemed to challenge our efforts.

From the Sparrenhorn to the Unterbachhorn the ridge has been climbed, and on August 29th, Messrs. J. and B. Hopkinson had been along the Unterbachhorn ridge towards the Nesthorn almost to the gap marked 3533 on the Siegfried map.

Leaving the glacier, we approached the Nesthorn from the first couloir from the Beichfirn. The gully was steep and narrow with séracs commanding the top on both sides, and evidently avalanche-swept, for great heaps of broken snow marked the centre, and, higher up, the tottering humps seemed ready to follow. Far above on the upper snowfields two parties, including ladies, were swinging with sinuous motion towards the summit. One of these was in charge of the guide Imboden.

From the couloir we used the steps of the advanced parties, or relied upon spikes screwed into the soles and heels of our boots : three in each sole and one in each heel. On the névé we found them splendid holdfasts; but for this purpose the snow must be of the right consistency, not soft enough to clog the boots and not too hard to prevent them sinking to the leather. I am decidedly of opinion that light crampons easily and securely fixable are useful aids on many snow mountains.

Several very steep and long snow-slopes brought us to a steep icy precipice which curved at the bottom to a rocky ridge and then down over beyond sight. A glorious view burst upon us over the Gredetschjoch, peak on peak in endless range, and far away to the south-west Mont Blanc in all his majesty:

“High o’er the rest, displays superior state,

In grand pre-eminence supremely great.”

Our leading party, consisting of the three Hopkinsons, had turned from the beaten track and struck along the p face of this cliff, cutting steps for the feet and tureen shaped holds for the hands. Slingsby, who had not been in his usual form during the ascent, now seemed to revive suddenly at the prospect of some excitement, and for the reminder of the expedition was very much alive. He cheerfully observed as we commenced to crawl along the traverse, ” If you slip here we shall all go to eternity ! ” Sic itur ad astra, indeed! The downlook was uncanny and the “starward-way” appealed more strongly to my fancy. However his inspiring observation braced me up. Beyond the wall of ice we followed the fringing rocks through a shallow trench to the rounded summit, which we reached at 10-30 a.m.

Just before we arrived at the top, Imboden and his lady climber stopped on their way down to have a few words with Slingsby.

On that Olympian height one would have thought there was no room for envy, hatred and malice and all uncharitableness! Wherefore “grieving cruel Juno ” should have twitted Æneas, our great President, I cannot tell. Or was she ” disguised Iris ” intercepted in arcu montis eager to wreak ” Saturnian Juno’s ” vengeance on the tiny ” Trojan band ” ?–Thus she accosted us–” I thought you were climbing without guides! Why use our footsteps instead of cutting your own ? ” Tantæne ‘animis cælistibis iroe? We trembled in that awful presence like guilty children conscious of our misdeeds, and, Slingsby with a mighty effort succeeded in suppressing his risibility. Imboden uttered kind soothing words and referred to his own ascent of Skagastölstind. Slingsby’s Norwegian reputation is pretty wide among mountaineers and the implied compliment was very gratifying.

Nothing was said about our plans and no reference was made to our deviation by the ice-wall overlooking the Gredetschjoch. We had had our “dressing down ” and fled to laugh at her twittering.

Over the snow mound of the summit we stepped on to a sun-warmed ledge where we spent upwards of an hour and enjoyed

” To sit upon an Alp as on a throne,

And half forgot what world or worldling meant.”

Here we lunched and admired the wide-extending view which included the untrodden aréte. Just before high noon we removed the spikes, re-roped, and began the new work by descending the steep granite rocks down a shallow couloir on a projecting ridge. The rocks were dry and sound, and afforded good holds. Great care was needed on account of the small loose stones which however were occasionally dislodged as the rope had to be frequently hitched. I managed to make a few small cairns on the ledges while waiting my turn to move. Slingsby in the rear skilfully performed the part of “player in hand.”

At the foot of this couloir a gully ran downward to the north and our porter, who was leading, could not manage to cross it. I told him to stop and Slingsby came up to him while I got over and once more we resumed the old formation. A little beyond the gully Dr. John Hopkinson unroped and came back to us and pointed out the way over loose rocks to the south-west face to the foot of an awful chimney, high and narrow, which required back and knee work, until we reached the main ridge itself above the Gredetsch Thal. The rattling of the stones as we crunched them down the terrible precipices is to be remembered with awe even now, rnore than ten years afterwards. The other side was evidently climbable by zigzags and Slingsby tells me a difficult pass has been made since, from the north-east to the south-west.

For some distance the aréte was pretty good and we made fair progress, but not equal to the Hopkinsons, who were moving in first-rate style. About half-way between the Nesthorn and Unterbachhorn we came to a dead stop in front of a lofty pinnacle haud partem exiguam montis – “No trifling chip of the old block,” which appeared impassable on the south side. On the north we saw the tracks of our leaders. The porter moved forward and found the steps cut into hard snow standing up as a huge flake a little apart from the gendarme. The little l crevasse formed by the snow shrinking away from the sun-warmed rock afforded a safe anchorage for the right arm.” With this purchase he got past and up into an opening beyond the rock spear and protected from the long fearful slope which extended sheer down to the Oberaletsch Glacier. I followed and when I got half way the man was “chuntering” like one possessed. He was simply lying down and had not made fast in any way. I had all the rope Slingsby could spare and remain in a secure position. There was nothing else for it, he had to move up towards me, to enable me in turn to get to the porter, pass him and get a safe hold while Slingsby joined us. Slingsby’s vigorous expostulations had failed to arouse him to a sense of insecurity or to induce him to take action. For my part I did not like the incident and I have never climbed in more uncomfortable circumstances. It was the porter’s first big expedition and though he went remarkably well the unusual surroundings and conditions at close quarters unnerved him.

We got along better after the last episode. The ridge, in places very narrow, was exceedingly rough and the gendarmes numerous; but we kept moving and no serious obstacle intervened. This portion of the climb reminded me strongly of Crib Goch. The rocks were loose and we had to cling with three limbs as each of us in turn dislodged stone after stone the clashing of which produced distinct sulphurous fumes. The ridge seemed interminable though exceedingly interesting and night was falling fast.

“Night, sable goddess ! from her ebon throne,

In rayless majesty, now stretches forth

Her leaden sceptre o’er a slumb’ring world.

Silence, how dead ! and darkness, how profound !”

The porter piloted us splendidly but kept up a continual T grumbling which only ended when we got off the mountain.

At last we reached the top of the Unterbachhorn and beyond, it appeared practicable to descend to the glacier to the south, but there seemed to be plenty of opportunities of getting crag-fast and a night out was not an inviting prospect as the darkening shadows obscured the face of the mountain. Even the company of our president, an expert in such affairs,[3] did not make me look forward to this delightful event with any pleasure.

We shouted to the Hopkinsons who had already reached the glacier marked Unterbächen on the map, and they struck some matches and yelled instructions which the rising moon enabled us to follow and by 8 o’clock we were off the rocks on the level glacier and on an easy line for home. We unroped and had a snack of food, and revelled in glacier water at every pool. Never have I had a more awful thirst ; like the Yorkshire farmer Who rode up to a village inn famous for its brew, sampled two quarts, decided it ” wor gooid stuff,” dismounted, and then went inside ” to hae sum.” At 10 o’clock we arrived at the Belalp Hotel, arvo optato, thoroughly tired out.

The last portion of the aréte consisted of very loose volcanic rocks which tore the lining all round my Norfolk jacket, and my knickerbockers were like unto those affected by our ardent pot-holers. A kindly porter at the hotel effected some repairs and for the remainder of my holidays I rejoiced in the possession of two blue patches staring from the neutral brown of my Harris tweed continuations.

The memory of the expedition is almost as vividly fresh in my mind as at the time it was accomplished, and writing this account of the incidents of the climb has renewed the pleasure I experienced on that memorable day–

Hoc est

Vivere bis, vita posse priore frui.

“The present joys of life I doubly taste,

By looking back with pleasure on the past.”