An Attempt On Kamet

By A. Morris Slingsby,

(56th Rifles, Frontier Force).

Kamet is a peak in Garhwal, some 25,442 ft. in height, on the borderland between Kumaun and Tibet. Though difficult to distinguish at a distance from its lesser satellites, it stands out boldly when seen direct from the glacier on its S.S.W. side, and is almost conical in shape. Seen from other directions it confuses the would-be explorer by the many shapes it assumes. From its northern slopes, which feed the Sutlej River, you look across to the great Kailus Range in the distance; its southern slopes augment the Alaknanda River, one of the great tributaries of the Ganges. From the summit the lesser ranges of the Himalayas are no doubt visible before they finally merge into the plains; indeed with a 9 in. heliograph one might perhaps communicate to the south with the distant military hill station of Ranikhet and with the Sutlej River to the north.

lt had never been climbed, or even seriously attempted, when Captain de Crespigny, of my regiment, and I set off early in May of 1911 from Ranikhet with the intention of making the ascent. We took with us some eighty coolies, as we had to carry stores for two and a half months as well as warm clothing for the coolies when at the higher altitudes. We also took two sepoys from my regiment and two servants to do the cooking, &c. As we had to change our coolies daily at each stage we also took two chaprasis belonging to the district in which we were marching, one of whom kept a march ahead of us to arrange for the next day’s supply. He also arranged for a supply of eggs and milk and chickens at each stage, as it was what is commonly known as the “foul” feeding season and meat was not easily obtainable.

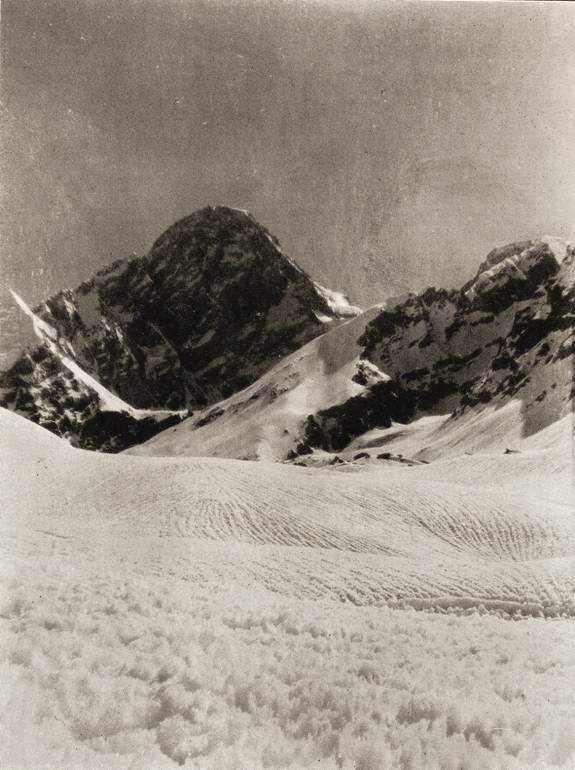

Some very hot marches brought us down to Kurn Prag on the Alaknanda River, only some 2,300 ft. above sea level, where we found the flies and heat very trying. Thence we gradually mounted up the valley to Joshimath, where the Rawul Sahib of Badrinath lives, a fat, squat little man with cataract in one eye, and of most unprepossessing appearance. He is a Madrassi, as it is the custom for the ruler to be a native of that distant province, for the man who first founded the temple at Badrinath came from there. With the help of his steward, an able and well-educated pundit called Bidiyadatt from Gwaldam, further south, though against his advice, as there had been a late and heavy snowfall, we got away towards Badrinath after two days’ delay, and, after spending the night at Pandukeswar, reached Badrinath the following evening. The devastating effects of the late snowfall were everywhere visible, the path was non-existent in many places, the telegraph poles bent double and the bridges carried away. At Badrinath we were delayed for fourteen days as no coolies were available, and we spent the time in attempting the Nalikanta and Satopant Glaciers, but were stopped everywhere by excessive snow. One day I spent in going up to Ghastoli, which is about 13,000 ft. above sea level. After fourteen days we began to get our baggage up to that place and to collect wood there, and at length, in early June, set off up the Ghastoli Glacier with ten picked coolies. Loads were reduced to 25 lbs. and every man was provided with clothes, sleeping-bags and boots. We managed to get the coolies along over the moraine, which they much prefer to snow, even when hard; and after some six hours reached an altitude of about 15,500 ft., where we camped. All night a cold breeze blew down the glacier, but we had Whymper and Mummery tents and were quite comfortable. We got away next day about 6 am. and found the going over the hard-frozen snow quite easy until the sun came peeping over the ridge below Kamet, when we soon found ourselves continually sinking in up to the knees. The melting rivulets on the glacier became noisy torrents and the coolies were much affected by the soft going. So far we had been going almost due east, but now, at a northerly bend, we rounded the corner and Kamet came into full view, looking so near and peaceful, with its ‘southernmost’ slopes still dark in shadow, that we thought our day’s trek nearly over. The glacier, however, seemed only to lengthen as we went further, the snow got worse, the coolies began to complain of the long march, and soon we had to look about for a place in which to camp; but we did not find one until we came in sight of two snow-fields at the head of the glacier, one obviously coming from the western slopes of Kamet, the other part of a lower range further to the west. Taking the easterly route we crossed over the centre of the glacier and pitching our camp on some rocky ground which turned out to be the first bit of moraine below the snow-field, sent back all our following except six coolies, the two sepoys and one servant, to our camp of the previous night.

We decided to stop here next day and prospect, but for some unknown reason we were most of us overcome with mountain sickness. Our camp was only at a height of 18,000 ft. and it was not very cold, but next day we found it difficult even to put one foot in front of the other and soon gave up any idea of reaching the col below Kamet. The following day saw us back at Ghastoli with all our stores.

A day in our comfortable camp, however, renewed my spirits and brought back that inexplicable longing for the mountains which all climbers feel, and two days later sent six coolies ahead and set off myself early the following day intending to reach our second or 18,000 ft. camp in one day’s march. I took with me one coolie and Gulab Khan, my Satti orderly, who accompanied Dr.Longstaffe and myself in the Karakorams in 1909. We climbed up to the first or 15,500 ft. camp in two hours, and passing the coolies, reached the second or 18,000 ft. camp in another six hours.

We stopped here for the night and started off next morning for the col at 6 a.m. I felt very fit and the coolies also seemed quite cheery. After two hours’ walking on the hard snow of the Upper Glacier, keeping on the east side of the great snow-field which stretches along the foot of the mountain so as to avoid the huge crevasses whose gaping sides overhung the Lower Glacier, we reached the foot of the col at 8 a.m. The snow-field had gradually narrowed until we now stood in a sort of amphitheatre of ice and snow and ice-covered rock, with steep sloping gullies stretching up to the col which lay to the north some 1,500 ft. above us, After an hour’s halt for the coolies to eat their food we set off up one of the smaller gullies, avoiding the main-gully I as it was, pitted with holes caused by stones which fell at intervals from a cliff overhanging the gullies diagonally to our line of ascent. I went first with three coolies on my rope and Gulab Khan followed with three more on his. A thin, crisp covering of snow over the ice sufficed for foot hold and saved us the exertion of step-cutting for some 300 ft., and then the surface hardened and the axe came into play. All went well for some two hours, though the coolies seemed to be getting very despondent. They were Bhutias, and hardy men, but, like so many natives, did not care about going where they had not been before. A thick mist now began to enshroud us, and I think this further terrified them, and, after three hours’ climbing, all but one were weeping bitterly and declaring that they would go no further. Go back, however, they dare not, as I had taken p off the rope and refused to let them go. By way of cheering them up I let them sit down and rest, and went on ahead by I myself and cut steps. We had now got above the snow and were climbing on a very nasty ice slope; the rocks also were coated with ice and I had to chip this off to make footholds before I dare let the coolies move. At every 100 ft. or so I hitched the rope to my ice-axe or round a rock and threw it down to the coolies and they came up one by one, hauling themselves along it. This method was necessarily slow, and the fog, which had become much thicker, made it increasingly difficult to keep to the route which l had mapped out in my mind from the bottom. We went on slowly like this until after ascending about 1,000 ft. we came, to more rocks and ice, where we had to cross over to the main-gully, and, after getting across it, climbed up by its easterly side. I had hoped the abundance of rocks would have made it easier, but they only added to the labour, for they were all covered with ice so hard that even at noon it was only with difficulty that I could chip off enough to get a foothold. Each coolie had to be carefully watched, for there would have been little hope of saving anyone who slipped, as there was nothing over which to hitch the rope. They were now very tired, dread of the unknown adding to their physical weariness, and it was only with the greatest difficulty that, with the help of Gulab Khan, after nine hours spent in climbing some 1,500 ft., we reached the top of the col (21,000 ft.) at 6.30 p.m. as the day was drawing to a close. The place was so steep that it was only with difficulty that I found a site for our Mummery tents. One coolie, overcome with weariness, sat down and, slipping his arm from the rope by which he held his load, stood up. Immediately and without warning the load slid away, and before we could stop it, went bumping down to the bottom of the gully, where we found it next day.

After settling down in camp I went on to the top of the pass and got a glimpse of Kamet and the country to the north. The mists slid away and the panorama before me was magnificent. Just below the corniced slope of the col a very high glacier, starting from the north-west side of Kamet, stretched away at our feet and curved gradually north until it merged in the low grey hills of the distant Sutlej valley. Beyond, the untrodden summits of the Kailas Mountains rose tier after tier up into the skies, girt here and there with long straight lines of hovering clouds, which seemed to add considerably to their height. Turning from this vast upland view of Tibet I looked eastward on Kamet. From the col a long snow slope swept up to a great rock-tower, itself a minor peak some 2,000 ft, above me, from which, if it were climbed, it would be necessary to drop down many hundreds of feet before again commencing to climb up the slopes of Kamet itself By going more to the east, however, and avoiding it altogether, it would, I believe, be possible to get on to a long continuous snow-slope and so to the top of Kamet. What manner of hidden crevasses lie between the col and this slope I cannot say, but the snow of course gets the full effect of the sun from early dawn, and here undoubtedly would be the greatest difficulty. To the south and west were countless small peaks and here and there a larger one that raised its head above, its fellows, their eternal snows flushing pale yellow in the rays of the setting sun. As I gazed on this sea of peaks, as yet untrod by man, the last parting rays of the sun lit up their upper slopes, the wind dropped, the peaks grew dim beneath the twinkling stars, the avalanches from Kamet ceased and over all a great stillness reigned.

Next morning, after a cold but windless night, I tried to get the coolies to come on, but they had all been somewhat affected by the altitude and their exertions of the previous, day and only one would accompany me. Though the reward of our efforts had seemed so close at hand, even within our grasp, I now began to realize that I could not go on and leave the coolies where they were, for they would surely have died. With the obstinacy of despair I went on up for about two hours to a height of I suppose some 22,000 ft., and then returned to camp. The snow was very soft and this served to confirm my misgivings of the previous evening as to the effect it would have had on our further progress. Before packing up our tents and commencing the descent I took the hypsometer readings and found the temperature at 10.30 am., in the shade to be still 2° below freezing, point.

We had some difficulty in getting down owing to the ice on the rocks, but eventually did so without mishap, and after camping at our 12,000 ft. camp again, descended the next day to Ghastoli. Thunderstorms and rain, the forerunners of the monsoon, came on, and further attempts at Kamet were obviously out of the question, and so, after a few days’ halt at Badrinath, we set off on our return journey to India.