In Memoriam

Web Note: While the names and locations of the battles of the Great War would have been well known to readers in 1921, they are possibly less well known these days. Click Here for a few maps and comments for the modern reader.

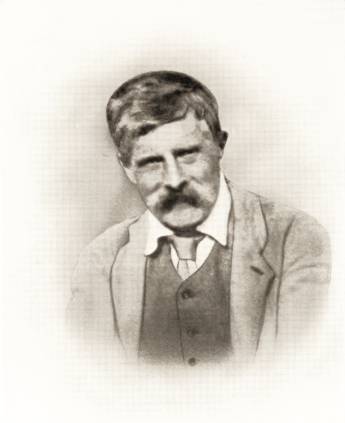

Charles Alexander Hill

On August 24th, 1914, the Club lost a Vice-President and one of its keenest members. Hill was educated at Rugby School and Trinity College, Cambridge, and took his M.A., M.D., and D.P.H. He joined the Club in 1902, but he had done a considerable amount of climbing before then; he at once became an enthusiastic pot-holer, despite his height, which was at times a handicap to him. His record for Ingleborough pots is probably second to none; in 1904 he assisted at no less than nine first recorded descents, these including Rift Pot and Jockey Hole. Hill’s articles on Scoska and Clapham Caves (the latter being published after his death) will not be forgotten by the Club.

Although more inclined to cave work than climbing, he had climbed in Norway and the Rockies, but he always returned with fresh vigour to the caves. Minorca, Ireland, Derbyshire, Somerset, and, last and best, Yorkshire, all knew him well. During the last two years of his life he was enthusiastic in the excavation of Fox Holes, although during that time he was suffering severely. Many members of the Club will have happy memories of the summer months of 1913 and 1914, which he spent at Clapham with his wife and children, to whom the deepest sympathy is extended.

Hill was well known in Masonic circles, being (at his death) P.P.G.W. of West Lancashire and Secretary of the West Lancashire Province; he was also a member of the Liverpool City Council, a position which he had held from 1907.

Hill had many friends among members of other climbing Clubs, among which may be mentioned the Wayfarers (Liverpool), of which he was a founder, the Fell and Rock, and den Norske Turist Forening (Hon. Sec. Brit.). He was a member of the British Association and read several papers on caves at the annual meetings.

After a heavy day’s work, either on the fells or underground, he was never satisfied until all records had been written up for future reference.

To those who met him for the first time Hill might seem reserved, but those who knew him loved him for his sterling worth, sympathy, and good-fellowship. The Club has lost a member and those who knew him best have lost a friend whom it will be hard to replace.

H. B.

Oscar James Addyman

Oscar James Addyman was killed in action between Zillebeke and St. Eloi on 5th February, 1915, aged 23. The second son of the late James Wilson Addyman, of Starbeck, he was educated at Aldenham, Leeds University, and Sandhurst, joining the Y.R.C. in 1910.

He was gazetted Second-Lieutenant, 1st Bn. East Yorkshire Regiment, but transferred to the 2nd Battalion, and joined at Calcutta in time for the King’s visit. A keen young officer, Addyman entered the Signalling School at Kasauli, and was personally complimented upon the excellent way in which his signallers passed their examination.

At the end of 1914 he returned to England with his regiment, and after three weeks’ preparation at Winchester, went out to France with the 28th Division. The regiment took its first turn in the trenches in February, and upon the 5th, the last day, he was observation officer and with Captain Wilkinson was observing the German trenches when a shell burst immediately in front of them, killing Oscar instantly and so severely wounding his companion that he died in the ambulance.

Devoted to his duty, Oscar Addyman worked hard, but he also played hard for his schools and his regiment at cricket and football, shooting in the Himalayas during his Indian leaves, and spending happy holidays, among the fells and pot-holes of Yorkshire, or climbing the great rock ridges and gullies of the Lake District.

We remember his presence on the first ascent of the Giant’s Crawl in 1909, at Gaping Ghyll the same year, and in the depths of Mere Gill, Hole in 1914. The Yorkshire Ramblers will recall his tall, handsome figure and the pleasant charm of his modest manliness, with unceasing regret, and will keep alive in their hearts the remembrance of a brave comrade, a, good son, and an affectionate brother, who has given his life for all that they love and cherish.

John Geoffrey Stobart

Geoffrey Stobart is one of the bright memories of the years before the war. The two youngest of the Club were the first to fall, both near St. Eloi in that first winter. Brief their days, the Club mourns their loss and their companions dwell lovingly on their great days on the hills.

The Club first saw Geoffrey as a guest at the Chapel-le-Dale meet of 1910, and the next day he and Kentish were among the five who broke out through the debris from Sunset Hole into the Braithwaite Wife Sink. He was then going up from Malvern to Cambridge, and in 1912 he joined the Club. That March he camped with his brother and Erik Addyman by Meall ant’ Suie on Ben Nevis in the wildest weather.

In September, 1912, he appeared at Wasdale, and his first day on the rocks was Keswick Brothers, Broad Stand, Scawfell Chimney, and down Moss Gill. A few weeks later he was at the Horton meet and descended Penyghent Long Churn, penetrating into its furthest recesses.

At Easter, 1913, we drove in his little cycle car from Darlington to Dunbar, and broke down there – a blessing in disguise – for as we saw next morning beyond Loch Lomond, the snowfall had been such we could never have got over Dalnaspidal, By the end of that week in the Nevis group Geoffrey was an expert on snow. On our only visit to the top of the Ben, with Ewen and Brierley, we burgled the Observatory, and saw the interior just as it was left 20 years or so before.

The world is smaller now these three, with many another comrade, are dead. We drove back from Dunbar on the Sunday and after tea he drove off. I never saw him again – so Fate willed.

In August, 1914, he was gazetted Second-Lieutenant in the Durham Light Infantry, and fell in a night attack with the Rifle Brigade at St. Eloi, on 15th March, 1915 a steadfast soldier and mountaineer.

E. E. R.

William Simpson

William Simpson died on 20th March, 1915, at Settle, in his 56th year. He was elected a member of the Club in 1905.

Until middle life he lived in Halifax, and in his youth came under the influence of the local group of naturalists who have left so strong a mark in Yorkshire scientific history. His chief hobby was the study of geology; he had written extensively on the subject of Millstone Grit, and was made a Fellow of the Geological Society in recognition of his work.

For several seasons he was engaged in research work on the Folgefond icefield, Norway, one of the largest glacier areas in Europe. He served for some years on the Committee for observing and recording glacial boulders, and was also a member of the Committee which investigated the underground waters of Malham and Ingleborough.

A man of many and keen activities, he possessed much social charm, and will be greatly missed by the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club and his numerous friends. A list of his papers will be found in Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society, Vol. XIX., p. 325.

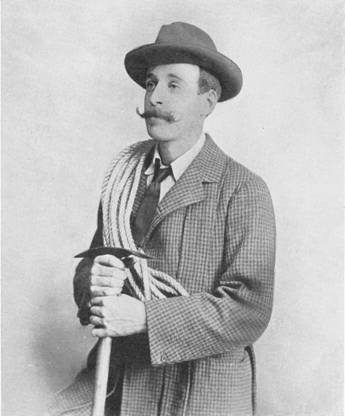

Arthur Morris Slingsby

1885-1916.

Amongst the many gallant young Yorkshiremen who have given their precious lives in the late horrible war, for as noble a cause as ever man fought and died for, the Yorkshire Ramblers deplore the death of Captain Arthur Morris Slingsby, the second son of Mr. J. Arthur Slingsby, of Carleton, near Skipton, who has suffered terribly by the war, having lost two other sons, one in France and the other in the Battle of Jut1and.

Morris fell on 8th March, 1916, in the battle for the relief of Kut-el-Amara “while most gallantly leading the final rush of the 56th Rifles. . . . On this occasion, as usual, he had worked his way to the head of the attack, and was leading on his men, although as Adjutant his place might well have been further in rear. Still the men trusted him and he knew that they would follow him.”

Brilliant though his military career has been, the especial interest of our Club is centred upon his magnificent mountaineering in the Himalaya.

In 1909 he joined Dr. T. G. Longstaff, a brother Yorkshireman, in exploring the unknown maze of the Eastern Karakoram (A.J., Vol. XXV., pp. 38 and 485). With Dr. Arthur Nevè they crossed the main range in June by the Saltoro Pass (18,200 ft. ), and discovered the immense Siachen Glacier, 48 miles long, and to their astonishment piercing the main range, and a feeder of ‘the Indus basin.

Recrossing the Saltoro, Longstafl and Slingsby continued their exploration when Neve turned homewards. The problem of escape from the Saltoro valleys was solved by Slingsby, who discovered the Chulung La (18,300 ft.). Longstaff writes –

“On Slingsby and his two orderlies, ably supported by Abdal Kerim, fell the trying task of assisting the coolies to face the steep snow slopes, now softened by the heat of the day. Few men would have succeeded as he did . . . . The glacier soon degenerated into a maze of crevasses concealed by a deceptive covering of new snow, through which the heavily laden coolies were constantly breaking. I quite expected we should have to spend the night on the Korisa Glacier, but just as it got dark Slingsby found a way off through difficult séracs.”

After this they set out on the ascent of a mountain well over 25,000 feet, but were beaten by persistently foul weather when high up the peak.

It was natural that after this successful Karakoram expedition and the experience gained in battling with glacial difficulties at great altitude, an enterprising young officer like Morris, endowed with robust health, great strength, and a born and proved leader of men, should wish to attempt one of the giants of the Himalaya. With bright hopes of success he set off in May, 1911, to attack Kamet (Gahrwal), 25,400 feet. The issue is described in his “Attempt on Kamet” (Y.R.C.J., Vol. IV., p. 19), but read also his letter quoted in the Alpine Journal, Vol. XXX p. 3 35. The records of mountain adventure show very few examples of such hard struggling under adverse circumstances. Not only did he lead his party up 1,500 ft. of especial difficulty during 11½ hours, not only for five hours was he, unaided, hacking coal-scuttle steps in hard ice, or hauling up heavily laden coolies, but all this herculean work was done in the thin air of 20,000 ft. above sea level. Morris himself could not have done this unless he had, by hard work and self denial, and by much training, attained absolutely perfect condition. He was the only one of the party of eight who was perfectly fit. Thanks to Mr. C. F. Meade, the col (21,000 ft.) up which he dragged his men will always be known as the “Slingsby Pass.”

In 1913, Morris obtained leave to make a second attempt on Kamet. I quote the following from his long and exceedingly interesting letter, descriptive of a most plucky attempt and marvellous endurance:-

“Since the first week in May, I don’t think we have had four fine days consecutively. . . . . I set off on May 29th with six sepoys and two coolies. We spent two nights at 19,600 ft. in that awful storm. We had very good Whymper and Mummery tents, which we had the greatest difficulty to prevent being blown away. They got nearly full of snow inside, and our bedding froze to the floor. During a lull in the hurricane we fled to Ghastoli after two nights of misery.

“On June 8th (1913), we made another start and in clear weather reached our first camp. Then it snowed again (goodness knows where the snow came from, as it has no business to monsoon up here till July 15th). It was fine again next day, but snowed again at our 19,600 ft. camp. We crossed the pass, which Meade honours me by naming ‘Slingsby’s Pass,’ and camped at about 22,800 ft. That evening it snowed hard. That night – ugh! I’ve never known such cold.

“Next morning, full of hope, I looked out at 4 a.m., but had little encouragement. We struggled up fresh snow towards the Gendarme, but at 23,350 ft. I was obliged to order a retreat, and really, though you may not believe it, my route is possible and not too difficult. The snow slope was nearly completed and the rocks of the Gendarme so near, but yet, under the conditions beginning to prevail, so far away. Oh, how miserable I felt after all that effort, and all in vain! Clouds came down on the Gendarme, the wind was fearful, and four of us had frost-bitten feet. We could but sit down and rub them, and then the storm came on, so what use would sitting down be under that awful sky?

“The storm which it brought lasted nearly ten days and finished with snow at 12,000 ft. We ran down and got into our sleeping bags for half an hour, and then went on again to our 19,600 ft. camp. Next day, fearfully done, we descended to Ghastoli. Two years ago I did it in four hours. It now took us eight, and we drank bucketsful of nasty glacier water, and, having eaten very, very little for four days, we were very done.

“I was unconscious for the whole of the following day. The doctor, who happened to be 40 miles away, came up as quickly as possible, but only saw me four days-after. I had started on my trip with influenza, so I imagine I was really too much run down to do what I attempted. I did not know this, and as an example to spur up my men I had carried a 34 lb. load on the glacier. Anyhow, whatever I had, it was very severe, and so far away from any European friends, I was apparently very fortunate to live through it. I am now quite it again and on my way back to my regiment.

“I am afraid you will think me a farce, but I really have a good excuse for my second failure. First, Todd going lame, then myself, and the horrible weather. . . . But we’ll get up yet, and by my route. I studied it carefully this year, and know the character and position of the difficult places.

“During the last two years, Kamet has put out buttresses where before she had slopes, she has inserted valleys, changed cornices into garden terraces. In fact, she has done her best to alter her general appearance. Deceitful creature! . . . A. MORRIS SLINGSBY.”

Upright, honourable, fearless, he has left behind him a reputation few can equal and none surpass.

W. C. S.

Wilfrid Ernest Waud

Waud was the youngest son of the Rev. S. W. Waud, Rector of Rettenden. He was born 28th July, 1875, and educated at St. Peter’s School, Eaton Square, from which he went to Weymouth College.

He entered the service of the Yorkshire Penny Bank at the age of eighteen in 1893, and remained with them until his death, 7th July, 1916, which, as far as is known, took place at Fricourt on the Somme Front. It is not known where he is buried as his body has never been identified. He joined the army 9th January, 1915.

“Your brother died leading his men to the assault, and how can a man die better, if die he must, than with his face to the foe and his men behind him . . . Let us pray that our sacrifices are not in vain.”

My first acquaintance with Waud was at the head office of the bank in Leeds in 1894. He was appointed my assistant and proved to be a most efficient and valuable helper. This business relationship led to frequent chats on many matters of mutual interest, and he was my companion on many a ramble. He soon became a welcome addition to our Saturday afternoon walking parties, and he joined the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club at my suggestion. From the first, in spite of his slender build, he showed himself to be very wiry and an indefatigable walker. His love of the hills was ardent and his enthusiasm in the work of the Club led eventually to his becoming a member of the Committee. He was in the Gaping Ghyll party of 1903, knew the North Riding and Pennines intimately, and had tramped, cycled, and climbed in many districts and ranges.

Waud was a man of strong views, sterling worth, a staunch friend, and a most dependable comrade. Under a restrained and calm demeanour there beat a warm heart and generous nature. To those who knew him best there will ever remain the memory of a man of the type our Club has been so successful in bringing together: men who have done so much to make the members value the good fellowship of the Yorkshire Ramblers. A tablet to his memory will be found in St. Michael’s Church, Headingley.

Harold Edward Kentish

(1886-1918.)

The last Yorkshire Rambler called to make the great sacrifice fell in action near Amiens on 30th March, 1918, and by his death the Club lost one of its most promising members. The son of Major Kentish, of the 14th Hussars, Harold Edward Kentish was educated at Clifton and at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich (1904-6), passing out ninth. He was a fine athlete and won the Officers’ Mile Championship, 1910. He also played Rugby for Richmond.

He joined the Club in 1910 and was very keenly interested in its underground explorations. Previously he had worked with Mr H. E. Balch and the Mendip Research Committee, in Somerset, with great success.

At the Club Meet in September, 1910, Kentish was one of those who broke out of Sunset Hole into Braithwaite Wife Sink-hole. In 1912 he accompanied E. A. Baker to Ireland, a visit which resulted in the opening out of an extremely interesting group of caverns near Gort.

In 1913 Kentish joined Baker and Wingfield in another Irish expedition and an account of their work appears in the Club Journal, Vol. IV., pp. 128, 138. Shortly after he went to Nigeria, and on the outbreak of the war he was on the West Coast of Africa, and received the special commendation of the Admiralty for his work on the railways.

In December, 1915, he was married to Miss Cicely Bailey, and in 1916 went out to France to command the 281st Army Troops Co., R.E., a command he retained to the end. He was mentioned in despatches and awarded the M.C.

In the great German offensive, several R.E. companies were formed into an infantry battalion with Kentish second in command, and on March 30th, at a village about 11 miles from Amiens, he was shot through the head.

Kentish was one of a number of the younger members of the Club to whom we looked for future guidance and leadership, and their loss will be greatly felt and deeply regretted. They have been claimed by a higher and greater duty, and though the Yorkshire Ramblers grieve for the loss of dear friends and pleasant companions, they know that their glorious and unselfish sacrifice has not been made in vain.

Charles Pilkington

A famous name in the annals of rock climbing in the British, Isles and of guideless climbing in the Alps is Charles Pilkington, President of the Alpine Club, 1896 to 1899. In the Coolins he was not only pioneer cragsman, but the first to map the group correctly. Abroad his name is inseparably connected with the Meije. The mountaineering world has to regret his death in 1919, and the Club has lost in him one of its earliest honorary members. The Alpine Joumal, in Vol. XXXII., No. 219, has a full memoir of this great mountaineer.

Frank Payne

All who knew Frank Payne must have heard with deep regret of his untimely death. He was only 56 and in full bodily and mental vigour, when he suddenly fell a victim to pneumonia, on 16th November, 1919, after four days’ illness.

Payne was educated in Geneva and Dresden. He made the ascent of Mont Blanc when only sixteen, and a few years later had climbed the Matterhom and Monte Rosa. One of his most stirring Alpine adventures was the first attempt to climb the Täschhorn by the Teufelsgrat, led by the ill-fated guide Clemens Zurbriggen, an attempt which was baffled only by violent and prolonged storm, during which the party had to cut steps down an exposed ice-slope to the Kien glacier. (Mummery’s party successfully forced the Teufelsgrat not long after this attempt.) It was during his residence in Geneva, in visits to the caverns of the Jurassic Limestone, that he acquired his keen zest for underground exploration.

Payne was married in 1891, and his married life was one of ideal happiness, for he found in his wife a comrade who shared his love for the mountains, and who bore him company in almost all his expeditions and adventures.

Though Payne had in early manhood become an expert mountaineer, circumstances in later years precluded regular visits to the Alps. Most of his brief holidays were spent in climbing at,Wastdale, Pen-y-gwryd, and in Yorkshire. He had also visited Scotland, and he used to say that an Easter ascent of the formidable Gardyloo Gully on Ben Nevis was the most memorable experience he ever had – a red-letter day in his mountaineering calendar. This was in 1911, and his daughter Dorothy, who has inherited her father’s skill in climbing, was one of the party. Wastdale was perhaps his favourite haunt and he was familiar with most of the best rock climbs there. Despite his somewhat short reach, Payne was a very capable and careful rock climber and a first-rate loader, especially under difficult conditions. He, in fact, possessed all the qualities of the competent mountaineer: skill and confidence in leadership, readiness and resource in emergencies, and a cheerful, imperturbable temper. On one memorable occasion in 1908, after a successful guideless ascent of the Finsteraarhorn, we witnessed from the hut the narrow escape of a party of five, who in attempting a sitting glissade brought down an avalanche in which they were partially buried and sustained severe injuries. Payne was quickly on the spot, rendered most efficient first-aid, and remained at the crowded hut tending the wounded for two nights, until their removal on sledges. Another party he rescued in ingenious fashion in the gloom of a winter night from the iced rocks of Scafell. A damaged climber he brought home safely from a Screes Gully.

Payne last visited the Alps, with his wife and myself, in 1914. The, weather was wretched and our only ascent was that of the Tsanteleina. The outbreak of war detained us some days at Val d’Isere. All the able-bodied men had been mobilised, and Payne got together a strong party of visitors to help the women get in their hay. He toiled all day, carrying on his back down the steep hillside huge bales averaging about a hundredweight.

Payne was a man of wide reading and many interests, an entertaining talker, and an original thinker, with a genius for invention and considerable skill in mechanics.

Frank Payne possessed a serene and cheerful disposition which, adversities were powerless to disturb. Owing to his lovable and wholly unselfish character, and absolute sincerity, he possessed in a remarkable degree the power of winning the affection and esteem of those with whom he came in contact. A shrewd judge of character and quick to detect insincerity and pretence, he was at the same time the most charitably minded and tolerant of men, slow to take offence and quick to make allowances, or with a touch of good-natured irony to condone an affront. In fair weather and foul, Frank Payne proved himself ever a staunch comrade, a true unselfish friend, and a most delightful companion. Those who are left to mourn his loss feel that there is a gap in their lives which can never be filled.

H. C.

When Payne came north to Chesterfield, in 1901, he soon got to work on the caves. A camping trip was made to Edendale and Ribblesdale to explore the ground, Elden Hole and Alum Pot descended; Somerset and Eastwater Cave were also visited.

The fifth descent of Gaping Ghyll was made in August, 1904, by hand haulage over a pulley fixed at the end of Jib Tunnel. From 1907 his enthusiasm, confidence, and persistence held together the parties of the successive Whitsuntide Camps by Mere Gill, broken only by the Gaping Ghyll Flood camp of 1909, till complete success was reached in 1912. Then followed Little Hull Hole, and in 1914 the second descent of Mere Gill. His last conquest, long deferred, was Hardraw Kin in 1919.

Payne loved camping, and was an expert in light and efficient outfit for all conditions; in the prime of his strength a tremendous weight carrier and tireless worker. Ever cheerful, confident, and resourceful, it is difficult to imagine the sense of safety to the men below in the knowledge that Payne was above. Inspirer of expeditions, the enthusiasm, which caught its spark from him has sent his followers to many a cave and many a climb. Though he be absent, his spirit will long be with us.

E. E. R.

Frank Horsell

Frank Horsell died suddenly on 14th December, 1919, at the age of 56. He was for many years a member of the Club, and although not taking a very active part in the work, he was a great lover of our Yorkshire hills and dales. Those of us who remember how strenuously he fought his way up the ladders of Gaping Ghyll, on some of the early descents, will always respect his courage and strength.

A man of many and varied interests, of a genial and generous disposition, the Club has lost a faithful friend.

FREDERICK BOTTERILL

During Whitsun, 1920, Fred Botterill passed quietly away before any of us realised the end was near. Used to open-air life, the close confinement of war work led to an untimely end, as certain as though he had been a victim of the battlefield.

To chronicle his many rambling activities would be impossible here and, perhaps, unnecessary, as many of our members have at one time or another shared with him the joys of crag or pot-hole.

His earlier efforts in the sport may be deserving of mention and, being younger brother, the writer was pressed into sharing them. Ingleborough was the first conquest within our limited means. Fare, Leeds return, 1s. 6d., the writer at half rate. Provided with “alpenstocks ” made from cart shafts (they were heavy!), we gaily rushed the “scenery” and saw Ingleborough Cap from Twistleton Scar. After a valiant struggle straight up the face the summit was won.

Later, Fred passed a long period in London where his love of mountains had to be satisfied with the lovely but inadequate Leith Hill.

In 1901, Fred came north, and thenceforward never lost an opportunity of indulging in his beloved sport. Most week-ends we cycled to Ben Rhydding to climb in Rocky Valley, not then being aware of the possibilities of Almescliff. Our first visit to the Lakes was accomplished on bicycles, via Ribblesdale. It was then that the charm of Stainforth first attracted Fred’s notice – charm which later led to his taking a cottage there. “Kern Knotts” will be remembered by the numerous friends who have had pleasant pot-holing excursions from it.

Fred spent a fortnight in Switzerland in 1902, and climbed the Dom, Sudlenzspitze, Nadelhorn, and Zinal Rothorn with Alex. Burgener, and without guides the Jägerhorn and Cima di Jazzi. He was in the Oberland in 1906, and spent a long season in a chalet at Arolla in 1910.

The doings by which he made history at home may be briefly stated-

1903. – Botterill’s Slab, Scafell, and Slab Route, Slanting Gully, Lliwedd.

1904. – With Payne, a large party taken down Gaping Ghyll without ladders or windlass.

1905. – Hunt Pot (second), Cove Hole (first descent).

1906. – Pillar Rock, North-West Climb.

1907. – Camp at Coruisk.

1909. – The Caravan at Wastdale Head; Abbey Ridge.

After the fatal accident to Rennison, Fred, then at the height of his powers, appears to have climbed but little.

Shortly after the outbreak of war he joined the army and had charge of the K.O.Y.L.I. Records Office at York, with rank of sergeant. When attempting to transfer to the Flying Corps, to Fred’s great surprise he was rejected on medical grounds, and subsequently discharged. He then went on to munition work at a shell factory, which completely broke down his health.

Coming between the earlier school of rock climbing, which culminated in O. G. Jones and the later sensational ascents of the rubber shoe devotees, Fred Botterill was entitled to rank as one of the foremost rock climbers of the period.

One of those who had climbed behind him says, “The thing which marked him out as in the super-class of cragsmen was his extraordinary power and the big margin within his limit of safety. His views were those of the safest climbers. On one occasion he summed up by saying that if he climbed as near the limit of his powers as some men he would stay at home, and on another occasion he expressed his confidence in his judgment and reserve of strength by the remark that he did not feel lonely till he had run out 100 feet of rope.”

He will be remembered, however, less for his achievements than for his unflagging bright spirits and resourcefulness under difficulties, and most of all for the helpful hand ever ready to aid a more weary fellow. These remembrances will always be dear to us, but We are fortunate in having a fitting memorial in one of Fred’s articles in the Y.R.C. Journal (Vol. III., No. 9).

In these extracts from the log of the caravan, we have a quiet style and an irresistible charm which make each reader wish it had been longer. One feels to be on the verge of discovering a complete philosophy of life.

“When our thoughts turn to the city of bricks and mortar, it seems like a maze, and we on one of its walls wondering why people fail to find a way out.”

Fred has found the great way out and we are left the poorer for his loss.

“And now . . . . all these things are past and gone. We have had a peep into a wonderful world, and it seems as if the edge of a curtain had been lifted and dropped again.”

M. B.

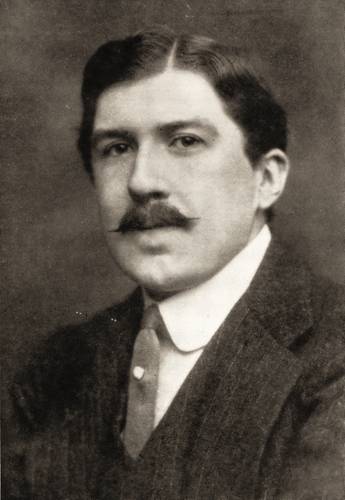

Reginald John Farrer

Born in 1880, Reginald Farrer was the eldest son of Mr. James Anson Farrer of “Ingleborough,” Clapham. Brought up in such a home it is little wonder that Farrer’s genius took the bent it did. He did not go to a public school, and it may be that by his upbringing he escaped that uniformity of outlook which, to some extent, mark a public school training.

He went to Balliol and there, like his father, he had a distinguished career and took a good degree. After leaving Oxford he travelled in Japan, Corea, and Manchuria, returning by the Canadian Rockies. His travel-book, “The Garden of Asia,” marked the beginning of his life’s work – travel in other lands in search of rare flowers, particularly Alpines, to enrich our English gardens, and the recording of his journeys for the pleasure of his friends at home.

The mountain limestone district of Yorkshire has always been celebrated for its flora, and Clapham is one of the most favoured places, with a range from almost sea level to over two thousand feet. In the glen running down from Ingleborough Cave, an artificial lake has been ‘ made with a steep limestone crag overhanging one shore. Here Farrer established a rock garden and brought thither botanical treasures from many lands. With the surplus of his plants he founded a nursery garden in the village for the sale of rare flowers.

By his books, “In a Yorkshire Garden” and “My Rock Garden,” he became known to a wide circle of flower lovers and captured a position of unique distinction in the realm of garden literature. The story of his Alpine wanderings is told in two books, “In the Dolomites ” and “Among the Hills” (Cottian and Maritime Alps), with a scientific accuracy and a wide human interest that marked a new era in botanical writing, for he writes as a lover or even as a devotee of his flower-friends in their Alpine sanctuaries. “In Old Ceylon” was the fruit of a journey to that lovely island in 1908. The call of the East had always been strong upon him, and in the mild religious teachings of the Buddha the obstinate questionings of his spirit found their completest answer.

In general literature Farrer made several adventures; three novels. “The House of Shadows,” “By Sundered Streams,” and “The Anne Queen” (Queen Anne Boleyn), and two plays, “The Dowager of Jerusalem” and “Vasanta the Beautiful,” came from his pen. They are all marked by much power and beauty. He was an ardent admirer of Jane Austen and declared somewhere in one of his books that her novels would be the very last piece of luggage he would discard in an emergency, not even excepting his brush and comb. Almost the last of Farrer’s writing is a memoir of her in the Quarterly Review in 1918.

Farrer intensely enjoyed congenial society, but he could be equally happy in solitude and travel, and he was ready in pursuit of his quest to abandon for long periods the luxuries and pursuits of home and of town. A hundred years ago another young Yorkshire squire did the like – Charles Waterton, of Walton Hall, Wakefield. So Farrer journeyed in the pursuit of knowledge into a far country; the outbreak of war found him in the far West of China on the wild borderland of Tibet, where he had the great good fortune to elude the followers of the bandit “White Wolf.” “The Eaves of the World” is full of keen observation and kindly human interest, and is brimful of his enthusiasm for the flowers he sought and found there.

Returning home he was rejected for active service but found work at the Foreign Office, under whose orders he visited our Western Front, of which he gave a vivid description in “The Void of War,” the last of his published books. His last journey was to the Alps of Upper Burrnah, to collect specimens for Kew Gardens. Circumstances deprived him of an intended companion, and on October 16th, 1920, he died alone, of diphtheria, at Myitidi, far beyond ordinary civilisation.

Farrer was not a man of strong physique, and we are the more compelled to admire the courage with which he compelled an unathletic frame to carry out the work it did. In a paper written for “Blackwood” and reprinted by permission in this Joumal, he describes with almost painful vividness his descent of Gaping Ghyll by the old rope ladder, a. trying experience for one of his build. This is, incidentally, the best description of the great pot-hole.

In conclusion we may say, with a very near relative, “He got a great deal out of life in his forty years and enjoyed it to the last. He could hardly have done otherwise or better than by travelling, as there was not scope enough for his energies at home.” We are indebted to him for bringing into our grey Western life some of the light and glamour of the East, and some of the colour and glory of the flower-strewn slopes of the high places of the earth, and the world is poorer by the loss of one whose sunny personality and enthralling pen did something to lighten the dull pilgrimage of his fellow-men.

J. J. B.

We are indebted to the Gardeners’ Chronicle for the loan of the block of Mr, R. J. Farrer’s portrait. – Ed.