Swildon’s Hole And The Mendips

By Arthur Bonner, F.S.A.

Speleological work among the Mendip Hills is conducted by two Societies – (1) The Mendip Nature Research Committee of the Wells Natural History and Antiquarian Society, with Mr. H. E. Balch – speleologist, geologist, and “prehistoric ” archaeologist – at its head; and (2) The Bristol University Speleological Society, of which Mr. E. K. Tratman is the active Hon. Secretary and Organiser. The present writer’s membership of both these Societies is an excuse for this contribution to the Journal. By agreement, the second – and junior – Society concentrates on the caves on the northern section of the range.

For the senior Society the year 1921, with its record drought, has been rendered specially notable by the completion of the exploration of Swildon’s Hole. This cave has been known since 1901, when Messrs. H. E. Balch and R. D. R. Troup took the leading part in opening it up. Until 1914, exploration was not carried beyond a point about 170 yards from the entrance and some 120 feet below it, where a waterfall proved a barrier. In that year – as our Editor has stated (Y.R.C.J., IV., pp. 273-4) – he and three others descended this fall and penetrated considerably beyond it. Messrs. Roberts’ and Baker’s turning point on that occasion – at the twin pot-holes – was not again reached until 23rd July, 1921, although in the interval several attempts were made, in which the present writer took a minor part.

On one of these occasions, in 1915, a wooden “boom” – an ingenious idea of Mr. R. H. Chandler’s – was carried in in pieces and erected over the waterfall, and the rope ladder was suspended from its end, in the hope that explorers descending would be clear of the stream; but this hope proved illusory.

On 23rd July, 1921, Dr. E. A. Baker, with his son and cousin and Mr. R. H. Chandler, got over 100 yards beyond the fall, and Dr. Baker went on alone to a point 210 yards beyond it,

where he raised a small cairn. On this, as on some other occasions, the party suffered from insufficient numbers and equipment.

On 1st August, 1921, a well-equipped party of 15, led by Messrs. H. E. Balch, R. D. R. Troup, E. E. Barnes, and J. H. Savory, of Bristol, reached the extreme point of the cave, some 267 yards beyond “Baker’s Cairn,” where, at a narrow flue, the water touched the roof, and progress was effectually barred. At this point, the aneroid registered 460 feet[1] below the entrance; and the distance therefrom is about 647 yards.

On 1st October a second strong party, 20 in number, under the same leaders again reached this choke; Mr. Balch took a number of photographs, and Mr. Troup and another carried out a rapid survey.

On 12th November a third and last visit was made for purposes of photographing; and an additional chamber was discovered.

The first and best known part of the cave, while presenting no difficulty to the practised explorer, yet gives him some good sport and exercise, and it is notable for its beautiful stalactites and stalagmites and for its many remarkable specimens of eccentric developments of these phenomena. The first 20 yards affords quite a nice little study in wriggling and screwing; for the next 50 or 60 yards a wet route may be taken by those who desire; and a few yards short of the 40 feet fall there is a squeeze, in an ascending crawl of about 12 feet through a small tunnel in a stalagmite barrier, which may be specially commended to girthy explorers – as our Editor has hinted (p. 274, Vol. IV.). This last, however, could be avoided last summer by a crawl along the water channel beneath: a muddy alternative, despite the plank which was laid down.

The “new” sections reached last summer and autumn, proved to be of much interest, and to contain features of exceptional beauty. The drought had reduced the stream to vanishing point, with a mere sprinkle at the waterfalls, and the pools in the pot-holes beneath these were but some 12 to 18 inches deep. A little beyond the first fall, the limestone is considerably contorted or folded; the calcareous deposits are good; beyond the second fall (the “second pitch” mentioned on p. 274, Vol. IV., about 20 feet) the twin pot-holes, with their deep pools and fine scenery, are impressive; and the scenery generally is attractive. The twin pot-holes, by-the-bye, appear to have more than 6 feet depth of water, and they are climbed into and round by the aid of a taut rope. One of the August party got a sousing there.

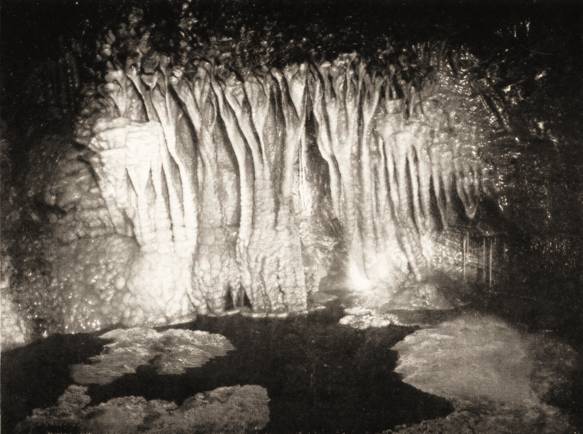

At 390 yards from the entrance, and ten yards beyond “Baker’s Cairn,” lies the entrance to “Barnes’ Loop,” the most striking of the discoveries of the August party. It is a branch from the waterway, entered by a narrow and irregular sloping ledge of stalagmite, which rises some 15 or 20 feet as it merges in a grotto-tunnel which soon descends and finally curves back to rejoin the waterway after a detour of 49 yards. Throughout its length, floor, walls, and roof are covered by calcareous deposit, its roof richly pendant with stalactites of very varied character and calibre, from the “straw” to masses with curtain or shawl attachments. The floor has many pools whose bottoms and sides are covered with coral-like “branched” forms, and whose clear water in several cases is, as Mr. Balch has expresssed it, nearly frozen over with crystals, leaving an opening in the middle through which the lovely interior is seen. The colour is uniformly white; the crystalline surface gleams and sparkles; and the whole grotto – or rather succession of grottoes – is of a loveliness so exquisite that one despairs of adequately describing it. Mr. E. E. Barnes was the first to enter this little paradise; hence its christening. Mr. Savory, of Bristol, an active member of the M.N.R.C., and an accomplished artist in photography, has taken some excellent photographs, some of which he courteously allows us to reproduce here.

The present writer, who was one of the October party, did not go beyond “Barnes’ Loop.” The information respecting the further portion is gained from Messrs. Balch and Barnes. Mr. Troup has provided the measurements throughout.

Beyond the Loop the waterway is not much decorated with stalactite, but is otherwise interesting, with pools and potholes and a chamber or two, boulder-strewn. A deposit of river sand and a tributary stream occur near the final mud choke. Some likely openings were observed hereabouts, including a chimney of some 80 feet height (Mr. Balch’s estimate). On November 12th – the third visit – while Messrs. Balch and Savory were photographing, a party led by Mr. Tratman gave attention to these and discovered another chamber, which proved to connect with this chimney. Mr. Balch has favoured me with the following note upon it –

“This place Mr. Tratman had succeeded in reaching, by climbing up on the south wall of the water channel. The climb was precarious and the slope in places rotten, but after a climb of about 30 feet, a good ledge marked the entrance of the new grotto. Entirely blocking the approach is a vast boss of stalagmite, so large that one does not realise at first that it is a boss of stalagmite at all, and indeed we debated for some minutes whether it were so or no. I think it may incorporate a bank of boulders in its mass, which is certainly 30 to 40 feet through its base. It is possible to pass round this to right or left, and on the left the approach is divided into an upper and a lower way, the latter partly blocked by stalagmite pillars and so far not passed.

Passing through the upper one the grotto is entered and before you a lovely group of pillars appear. They stand all round, some on the great boss already referred to, some on the left wall, and a large number away in the background. The surface of the great boss is covered with very fine branched stalagmite, and this also covers every one of thousands of fallen pencils and stalactites which carpet the floor in great profusion. Dropping down steeply, this floor is reached and it is seen that it drains from every direction towards a pit in the floor, from which a vertical drop of 80 feet occurs to the waterway below, from which, as before mentioned, it is visible. Standing in the middle of this chamber, to whichever way one turns, most beautiful stalactites and pillars appear.

From immediately overhanging the pit, a passage is visible, which can be reached without risk, and passing some very fine pillars, we entered it. Here are some strange and grotesque human resemblances, and from here one of the finest photographs was obtained. The floor ascends at a gentle gradient and is formed of dried and cracked cave earth. The floor was smooth and level and it reached upwards for about 50 feet or rather more. The termination is a pretty little archway looking into a grotto which has not been passed, as it is entirely filled with beautiful stalactites which would be destroyed in passing.

I estimate the total length of the grotto is about 70 feet, and its maximum width is slightly more than the great boss before referred to. It is very lovely, richer in pillars and stalactites than any other part of Swildon’s Hole, but entirely lacking the glorious whiteness which is the special virtue of Barnes’ Loop. The carpet of fallen pencils suggests to me that it is of great age and that on rare occasions of enormous flood a gale of wind must rage round the grotto and bring them down. It stands just at the right place for such a thing and I cannot otherwise account for it.”

The main stream at Swildon’s has now resumed its normal conditions, and when I saw it this Easter it seemed a little fuller than usual. When Barnes’ Loop and the Tratman Grotto will again be accessible no one can tell.

Elsewhere in the Wells area the main activity has been at Hill Grove, about three miles from the little city, where a “swallet” or swallow-hole has been for some years an object of interest. It lies in a wooded hollow rather less than 800 feet above sea. Mr. J. H. Savory has been a leading worker in clearing and excavating the swallet in the hope of gaining access to negotiable fissures etc. by which the stream makes its way down to join the waters from Swildon’s Hole and Eastwater Caverns to form the River Axe in Wookey Hole. Work here culminated in a special effort this Easter (1922), after which it was reluctantly decided to abandon the scheme – for the present at least. At Easter, 1921, Messrs. Bird and Bonner discovered a small cave in the cliff above and near Wookey Hole, which seems to be worth investigating. It is a simple rift of some 50 feet length, tapering in width from 3 feet at bottom to nothing, and 30 to 60 feet (?) height, with an earth-flooring of considerable thickness, which may repay digging for archæological finds.

The Bristol University Speleological Society exhibits the natural vigour of youth and maintains excellent activity. Its members are largely medicos, and women are admitted. Their most extensive operation, the discovery, opening up, exploration, and surveying of the Keltic Cavern, has been alluded to in this Journal (p. 267, Vol. IV.). A later and supplementary explanation of this cave is that it was a great rock shelter, inhabited, the roof of which fell and choked the sloping floor with boulders. The boulders are notable: one of them – supported at each end and called “The Bridge” – is exceptionally huge and must weigh some scores of tons. There is much calcareous deposition, and the stalactites include some interesting “eccentrics.” At the suggestion of the Ordnance Survey Department, the name “Read’s” is being substituted for ” Keltic ” Cavern. The Society is busily engaged on digging out the deep earth floor of a prehistoric habitation cave near Rowberrow, at the north-west corner of the range, at the junction of two hollows, near the well-known Dolebury Camp; and on similar excavations at Aveline’s Hole in Burrington Combe.