Mountain And Sea III

By Matthew Botterill.

That men should spend all the time they can spare from everyday life, uncomfortably striving up mountains, crawling wet to the skin in gloomy pot-holes, or tossing in wild seas a prey to the elements, and moreover treasure their achievements therein more than those of everyday life, seems incredible to such as are not Ramblers.

It is only this break away from civilisation, however, which can give to at man a true perspective of life. It seems to me at this moment that rambling is as important if not more important than the petty round of our communal life; for the true rambler, be he of, or outside a club, is preserving for the race some of those essential qualities which mankind will require when this temporary civilisation, now rotting from a surfeit of knowledge with too little wisdom, finally passes.

So, carry on, Ramblers, this Joumal is of more importance than newspaper or political organ.

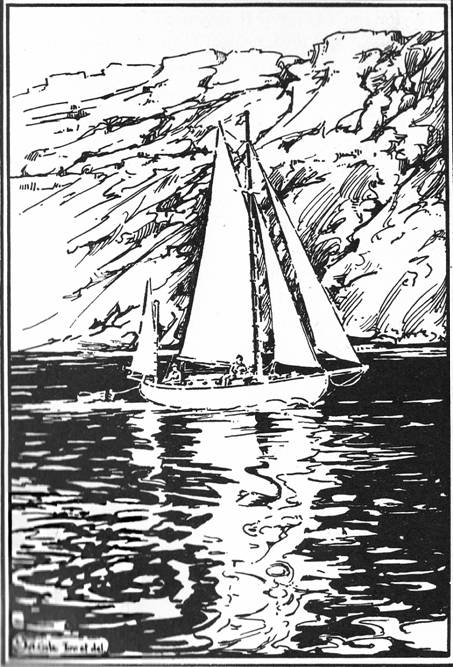

The Cobbler. ‑ In May, 1922, the Yacht Molly, after some preliminary cruising, is working up Loch Long towards the mountains. We are favoured with a fine day and very beautiful are the views of snow-covered peaks, including Ben Lomond and that elusive Cobbler. Having founded Knap Point, the beauty is marred by a torpedo testing range. To avoid these experimental death dealers we run Molly close to Ardgarten Point and thus get aground. From this situation we are finally pulled off by the launch used for retrieving torpedoes, and find ourselves towing alongside two fizzing and blazing specimens.

We had just laid our anchor in a little bay convenient for climbing, when the chief Torpedo Officer arrived alongside in a powerful pinnace, to assure us they had piled up torpedoes in that very bay; that he could not guarantee the direction of experimental types; that a torpedo striking the yacht would go straight through; and that anyway it was very squally just there; and would we not prefer a buoy he would have cleared for us a quarter mile up the loch; all in the most courteous manner possible.

It was clear that if we had come to see torpedoes we were not welcome. We accepted the buoy but declined the proffered tow at I2 knots, to show our independence and keep our shirts dry. After tea we used the engine and ran up to make fast to the buoy, which we were very glad to have. The next day Skipper and Steward climbed to where they supposed the Cobbler was, for a thick mist obscuring everything soon turned to an equally opaque and very heavy rain. The final part of the ascent was not unlike Deep Ghyll, Scafell, and contained new snow on old ice, thus requiring more than ordinary care. On descending from the summit (it was probably the Eastern Pinnacle) we were so wet that a sitting glissade on the lower slopes of the rapidly melting snow could not make us more so.

A very wild night was succeeded by a still wilder day, and it was necessary to shackle chains to the buoy to replace thick warps nearly sawn through. We were glad of that buoy.

On returning down Loch Long, when just above Whistlefield we were struck by a whirlwind, made visible by the column of water it was raising from the sea. Our staysail was nearly lost in the scrimmage which ensued. It is these little occurrences that make Scotch cruising so full of incident.

Caisteal Abhail. ‑ Some few days later Molly proudly sails into Loch Ranza, so that we may renew our acquaintance with the “Sleeping Warrior.” At 2.45 a.m. I awake in pitch darkness with a presentiment that all is not well. Dressing quickly, l look out and, by the very first gleam of dawn, see we are rapidly drifting towards the reef which bars the eastern opening. Fortunately the engine condescends to start and we pull back to safety and renewed sleep after laying out three anchors. How it does blow in these hills!

For our ascent we enjoy a perfectly gorgeous day and set off by the Glen Sannox Road. Having left the road we find it exhausting work to walk over those abominable grass tussocks to Upper Glen Sannox. Near a little tarn we surprise an unusual bird (probably a Crested Grebe). The heather is of extreme length and so covers boulders and holes as to render going very treacherous.

Skipper and Steward roped, ascended the gully leading to the eyes of the Warrior’s profile, traversed his features and descended by the warts on his neck, thus completing the ridge walk we had contemplated on our previous visit. But what a difference; gone are the bottomless precipices, gone are the endless chimneys; for they were but tricks of the mist! And what a compensation ‑ clear like a map, Ardrishaig, Tighnabruaich, Rothesay, Millport, Galloway, Ayrshire, Ben Lomond, and the Argyll Mountains.

Suilven. – Becoming more ambitious, Molly set sail in June, I922, with only Skipper and Steward aboard, rounded Cantyre and Ardnamurchan and put into that offensive little hole Mallaig, where she was jostled by trawlers.

Skipper of Molly (to Trawlerman shovelling mackerel into baskets on the deck high above).‑ “Are those fish likely to fall on my clean decks?”

Trawlerman (reassuringly). ‑ “No, sir!”

Skipper. ‑ “If half a dozen did you’d never get them back.”

Timed with a stop watch it took 7 seconds before that Scotchman saw the joke. The fish came over immediately afterwards and they were good!

We gladly left Mallaig with its half ton of decaying fish offal as a permanent feature of the pier, and coasting the whole length of Skye, entered Loch Broom less than a week out from Tarbert. There was so much rain on this journey that the day of our entry into Loch Broom was a red-letter day. It was perfect; the hot sun was tempered by a beautiful sailing breeze. We stood into Gruinard Bay and the collection of islands and rocks (Summer Isles) provided a scene of ever-changing beauty. So delightfully warm was it, that whilst Molly sailed herself for miles without attention, her crew sat with their feet dangling in the sea, smoking and yarning. Anchored comfortably off Ullapool, we saw this magnificent day finish off in the grand manner, the magic of the setting sun transforming Carn Dearg into a crimson giant towering over his attendant purple satellites.

Two days later Molly’s Bo’sun arrived and we set sail immediately for Loch Inver. It was clear enough on our entry to see that wonderful peak Suilven, but soon clouded over and turned to a depressing, soaking downpour.

June 19th, 1922, was unusually clear and sunny up in the north with a rather violent north-westerly breeze. Bo’sun and Skipper enjoyed the seven-mile walk up Glen Canisp and then lunched by a stream. We found it subject to ebb and flow with intervals of one minute; max. range, 5 in. This interesting phenomenon was caused by a large lake whose waters were in periodic oscillation.

Suilven has a well-marked horizontal band and we made for this and traversed on it, but were held up at its westerly extremity by the excessively violent wind, so that we dare not venture on to a sort of mantelshelf which seemed the only continuation. We retraced our steps to a prominent buttress consisting of decrepit rock, moss, and very steep grass. I am continually being surprised at the steep angle at which Scotch grass and alpines will flourish. The climbing required a good deal of caution and occasional stretches of steep clean rock were indeed welcome.

From the summit there was a good view of the innumerable tiny lochs which dot the country round almost to Cape Wrath. To the south we distinguished many mountain ranges, the foreground being dominated by those isolated peaks, An Stac and the Culs; but the impressive view was that of the eastern peak of Suilven which from the western peak presents an incredibly steep looking pinnacle. We descended on easy ground between the two summits.

There follows in the log an account of the voyage from Loch lnver to Little Loch Broom, where we anchored about a mile from Dundonnell Inn, which is the centre for much of this northern climbing. The distances of some peaks from this centre are such that if they had to be walked it would surely leave little enthusiasm for climbing. The An Teallach Range, though, is quite near and this was our objective. Very unsettled weather overtook us and the only result of a sortie was that we got half-way up, had an inadequate glimpse of distant crags and a wetting, more than satisfying.

The bad weather followed us down to Loch Torridon, save that we had a day of light airs for our entry therein. The outer loch is wide and affords no clue to the existence of an inner loch. The entrance to the latter is a narrow passage hidden by rocky promontories and it opens out with dramatic suddenness, revealing an unforgettable sight of mountain and sea. Molly drifted rather than sailed into Ob Gorm Beg (Little Blue Creek), an anchorage chosen from the chart, which proved intensely beautiful and well sheltered, and in which we found fresh water falling into a fern-clad sea cave ‑ a veritable fairy grotto. A hot humid atmosphere with almost continuous rain made the slightest physical effort painful on the next day, so that here again climbing was missed. We managed to stagger as far as Torridon village to a place marked on Bartholemew as “Pub. Ho.” but which in reality was a post office.

And now Molly was to bid adieu to the mountains and cleave, what were to her, new seas. Changing crews at Tarbert, with Wingfield as a most efficient second in command, we sailed her to the south coast, where she was to slip across channel many times (always with different crews), visit the (Channel Islands, Normandy and Brittany, and finally in June, 1923 to be put to the great test ‑ a gale in the Bay of Biscay:‑ and to lose the faithful little punt which had followed her so many thousand miles. Her many adventures belong rather to the sea than to the hills and so we must omit them. This 1923 season has been one monotonous round of indifferent and heavy weather, so that the sunshine we sought in the south has been denied us. September saw Molly once again gladly turning her bow to the magical northland, and she now lies in Tarbert waiting the first breath of Spring to begin anew the search for joyous adventure.