Peaks And Porterage In The Pyrenees

By G. R. Smith.

Aug. 8th, 1923.—-I cannot bear to write of that terrible night spent in a third class railway carriage between Paris and Bordeaux !………………… Another veil must be drawn over the journey from Bayonne to Pau. The carriages were so hot that one had to pad one’s seat all round to avoid being scorched. At every station the engine was abandoned by its staff, who went and paddled in the neighbouring river. At Pau, in a grocer’s shop full of electric fans, we bought supplies of bacon, tea, coffee, sugar, cheese, bread, candles and tinned food. Wafted out on a bacon-scented breeze, we headed gently through the scorching streets for the station. Here we caught a train for Laruns, the railhead ; that night we bivouacked outside the village.

Aug. 9th.—We started on an uphill tramp through pine-forests and over long stretches of open road which flung back a blistering heat in our faces …. We tried in vain to quench a most terrible thirst. Each was carrying an enormous weight. In addition to a necessary change of clothes, shorts and espadrilles, cardigans, sweaters and mufflers for warmth at night, we had a tent (which just held three), ground-sheets and army blankets ; two saucepans, a frying-pan, knives, forks, spoons, plates and mugs ; lanterns, cameras, mackintoshes ; and food, a very heavy item, since it consisted chiefly of tinned meat and tinned fruit. Villages out there are few and far between, and we had to get in Sufficient food at a time to last us for at least five days.

We passed through Eaux Chaudes and Gabas, and at length pitched our tent beside a waterfall above Gabas. After a bathe and dinner we went through the ritual of turning in, covered the food with mackintosh squares and placed with it some dry wood for the morrow’s fire, donned a vast amount of extra clothing, and crept one by one into the tent.

Aug. 10th.—We breakfasted by lantern light, intending to climb the Pic du Midi d’Ossau (9,600 ft.). Our French guide-book had labelled this ascent impossible without a guide, but we were anxious to discover whether this statement was true.

We started in the half-light up a very stiff path through the woods. The track soon disappeared and for the best part of an hour we had to scramble through thick undergrowth and fallen trees. At last we reached level ground, and the trees fell away on either side. In front of us stretched undulating grassland, reminiscent of English downs, which climbed to the rocky foot of a pass. The line of the pass and the Pic du Midi ahead of us were free from cloud, and had that clear-cut look which the early morning atmosphere always lends to hills.

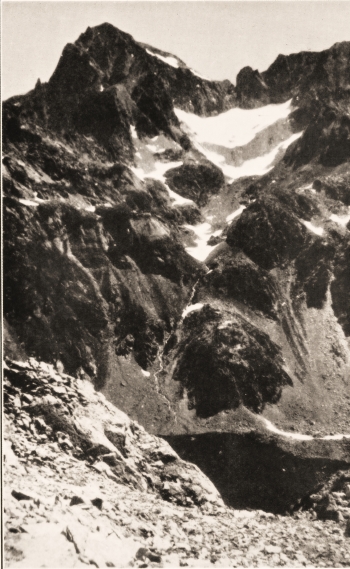

We followed an ill-defined track, skirting a low forest of stunted bushes, and finally reached a broad belt of loose boulders and broken rock. The sun was well up by the time we had reached grass again and we were on the sunny side of the pass. Although the hour was only 9.30 the heat was overwhelming, and we were completely exhausted when we arrived. From here the Pic stood out in all its grandeur. On the south-east side it rose in precipitous cliffs from its very base, and towered above us, its buttresses and pinnacles glowing red against a deep blue sky in which some eagles were slowly wheeling.

We clambered to the foot and tried to find the route recommended by the guide-book; but failing in this we struck up on our own over some rough rock, rather like the rock on Crib Goch (Snowdon). This deteriorated into scree which, combined with the intense heat of the sun blazing on our backs, reduced us to a terrible state of weakness.

Near the top we ran into some snow and filling our hats with it we staggered to the cairn at the summit and collapsed. After a meal we extended ourselves along the rocky ledges on the shady side, overlooking France, and slept. Fortunately none of the clouds, which filled all the valleys below, rose during our siesta and we awoke to find the summit still clear.

The descent was very easy, since we discovered the correct route, which consisted of three chimneys fitted with crampons (Pyrenean for spikes or pitons). The idea of taking a guide up such a climb seemed ludicrous ; the rope was not once needed, and we had left our axes with the rucksacks below. We had the same experience in all our subsequent climbs, until the ever-recurring phrase, ” guide indispensable,” became a byword.

11th.—We struck camp and returned to Gabas, where we collected provisions for the next five days. These consisted of two enormous loaves of bread, like millstones in size and shape and not unlike them in substance, and numerous tins of sardines. Thus fortified we followed the road up the Val d’Ossau which we left towards evening, striking off up the Val d’Arrius, a trackless, wooded pass. That night we camped above the woods at a height of 6,000 ft.

12th.—-After a terribly hot climb up the Col d’Arrius, we pitched the tent just above the Lac d’Artouste, in whose waters we bathed and vainly fished. Heavy rain drove us back to the tent which we found surrounded by standing water and looking like Noah’s Ark. So we decided to try and find the Refuge of Arremoulit. This was not marked on the map, and the clouds were down, but as anything seemed preferable to sleeping in a lake, we packed up and attacked the Col d’Arremoulit. From the top of the Col, and a little above us we saw some stone walls without a roof which we reluctantly decided must be the refuge. The clouds had lifted and were piled in yellow masses on the peaks : it was a wild world of grey stone into which we had entered, not the broken jagged rock so much as the smooth worn stone of antiquity, pierced by narrow lanes of grass which radiated in all directions. Deep glassy lakes, linked by waterfalls, reflected the cloud light ; blocks of stone lay about like ruined temple pillars. It was a land without life ; only water, rock and bleached grass.

We reached the refuge, which stood on a narrow strip of rock separating two lakes, the one about twenty feet higher than the other. After clearing the floor of what was left of the roof, we spread our ground sheets and blankets, and prepared ourselves for a very cold night.

13th.—We packed up early and continued over the Col d’Arremoulit. At the top, the frontier between France and Spain, we lunched, one foot in either country, then scrambled down an almost perpendicular slope, viciously studded with unsteady boulders till we arrived at the edge of a deep-blue lake bounded by straight, yellow cliffs. Here we pitched camp.

14th.—Laden only with the essentials for a climb, we attacked the scree slopes at the foot of Mont Balaitous. It was still twilight, but after an hour’s climbing we noticed the peaks behind us blazing with vivid ochre light. Away to the South the hills of Spain bloomed like pale roses in a bed of lavender.

Meanwhile we had reached the snow-covered lake which we crossed, jumping the deep-green crevasses. Continuing over more snow on the farther side, we reached a couloir, up which we had to cut steps. This brought us to the foot of a loose boulder climb up the side of an arete. Here was every variety of flower, stonecrop and heather nestling in clefts of rock, gentian, pink, forget-me-not and violet, crowding together with white and yellow daisies, dwarf thistles and thyme.

At the head of the arete we rested, and watched the mists in the valleys dissolving before the sun’s rays, grateful to be on the shady side of the mountain ourselves. Then came the ” Grande Diagonale,” whose merits were so enthusiastically extolled in the guide-book, though in the words of M. Soutiron, ” il est indispensable de garder tout son sangfroid.” It proved to be an unpleasant scree-path traversing the steep northern face of the mountain. The showers of stones we dislodged clattered down below out of sight. During a pause for breath, we heard a renewed fall of stones below us, and peering over the edge, saw an izard bounding over the scree. We plugged away at the track for another hour and then decided to abandon it and take to the rock on our right. This proved to be thoroughly sound, and within half-an-hour, without having to rope up, we were at the summit. It was like an English summer’s day on top, the sun shining with pleasant warmth. We were 10,300 feet up, higher than most of the neighbouring mountains which were thinly veiled in early morning mist. Westwards we saw the bold outline of the Pic du Midi dominating the surrounding hills.

After a long rest and a meal we started down the southern side. Loose scree merged into snow and rocky terraces. The climb down to the jammed boulder at the head of the Breche Latour was distinctly difficult. We had to rope up and go cautiously down an arete which ended in a precipitous drop to the valley on the other side. Below us, half right, lay the black gulf which was our objective, while facing us were overhanging, unassailable cliffs of rough, red rock, deep in shadow. A traverse from the arete brought us to a point above the boulder, whence we were able to climb straight down, on rather insufficient hand-holds. The boulder lay at the apex of two steep couloirs, and we expected to find glaciers reaching up to this point on either side, but not a sign of one could we see. The exceptional heat had caused the ice to melt, leaving behind an extremely narrow and very steep gully full of loose stones. I went first to explore, and got as far as a wedged boulder : flattening myself against the side to avoid the shower of stones which hurtled past, I awaited the others. Peering over the boulder we saw the glacier, but it was forty feet below us at the foot of smooth cliffs down which descent was impossible. The only thing to do was to go down on the rope : I was the first to be lowered, then my brother, then the rucksacks and axes, and lastly A., who came down on a double rope. Roping up again, we cut steps down the steep couloir, until, on reaching the easier gradient of a large snow-field, we were able to glissade. The remainder of the descent was uneventful: we again crossed the lake, and halted for food and rest at a point whence we could overlook the Lakes d’Arriel, beside one of which was our tent, a white speck on the green grass. We got home at 4.30, bathed, shaved (for we hoped to enter civilization on the morrow) and had tea.

That night we re-read with enjoyment the directions for the climb in the guide book. Therein Mt. Balaitous was immortalised, in fulsome language, as ” le plus attirant, le plus grandiose et le plus loyal des sommets pyreneens.” We turned in with the comfortable feeling that we must be “pyreneistes exerces non sujets au vertige,” by whom alone the peak was assailable.

15th.-—We struck camp and set out for the Spanish village of Salient. After four hours’ scrambling over rocks and slithering down deadly scree, deprived of all sense of balance by the devilish loads we carried, we reached the river Agua Limpia. Here we finished off all that remained of our provisions ; the banquet consisted of half a very stale loaf of bread, one small piece of cheese, in size and substaenc suited only for a mouse-trap, and one lemon.

Our next obstacle was the passage of the Paso del Oso (Step of the Bear). The guide book was singularly vague in its directions. For three hours we toiled through thick grass and hemlock waist high, while the stream raced through narrow walls of rock 300 feet below us. The farther we went, the narrower and more thickly wooded did the gorge become. Just as we were thinking we should have to camp there and subsist on berries, we found an opening which did not end in a precipice, and following this soon came to open grass land. Somehow or other we covered the remaining six miles to Salient, and collapsed in the square, flagged hall of the inn owned by Enrique Bergeur.

16th.—We got up joyfully conscious of the fact that for once we had not got to prepare our own breakfast. Lighting a fire with damp wood, lying flat and blowing it till one’s lungs are full of smoke, and then gloomily watching some case-hardened bread being fried in sardine oil to be rendered edible, are some of the under-emphasized joys of camping- out Our bill being made out in Spanish money, we had to convert it into its French equivalent. All the chocolate-sipping patrons began to work the sum out : competition ran high, as in all paper games. All the answers being different from one another, we chose that of a corpulent, white-clad gentleman who looked like a banker.

We took the road for Panticosa and bivouacked that night just beyond the village.

17th.—On entering Bains di Panticosa, a modern watering place, we were immediately adopted by a ruffianly ancient, toothless, blear-eyed and loquacious. He wore a felt hat, green with age (though undoubtedly belonging to the civilized family of black hats, it was a cross between a bowler and a shovel hat), a sort of braided Eton jacket, a red cummerbund, shorts with coloured laces at the knee, stockings and sandals.

……………………. That night we camped on a high grassy plateau overlooking the town.

18th.—We spent this day and the next day in camp, gas-tronomically indisposed. The goat is omnipresent: you meet him in the hills, and you taste him in all your food— milk, bread, cheese and even wine, for a gourd is made of goat-skin, with the result, as Belloc sagely remarks, you are never tempted to vinous excess. Our only visitor was a bearded, bespectacled professor, carrying his coat and trousers over his arm!

We took three days over the trip from Bains di Panticosa to Gavarnie, by way of Bujaruelo. At Gavarnie we pitched our tent on the top of an open bluff, encircled by low bushes which gave it privacy without in any way obscuring the view. Behind us were high woods which climbed steeply, in front a distant view up the Port de Bujaruelo, on our left the majestic Cirque surmounted by a line of famous landmarks, on our right Gavarnie, and below at our feet the ever-crowded road connecting the town with the Cirque.

Smoking our after-breakfast pipes we lazily watched the crowd of trippers streaming up the road. From our Olympus we could command the whole kilometre route from Gavarnie to the Cirque : every day, from ten o’clock in the morning till five o’clock at night the road was a crawling mass of black, relieved here and there by the bright colours of parasols and dresses.

23rd.—After making ourselves as presentable as possible we dropped down and walked into Gavarnie, in the opposite direction to that in which the solid stream of humanity was progressing so laboriously. It was a quaint crowd which we met, composed chiefly of typical trippers attired in their uncomfortable best clothes : all carried newly-purchased walking-sticks, labelled in florid lettering with the name Gavarnie. A few of the wealthier carried long, spiked alpenstocks, branded as souvenirs even more obviously. The real plutocrats rode on mules or ponies : fat women, held in position by muleteers and pony-girls, jogged along; jolly, corpulent priests, with cassocks tucked up to their waists, bestrode minute donkeys, giving a Chaucerian effect to the procession. Everyone seemed to be in a frantic hurry, which was strange considering the appalling heat, the roughness of the road and the immobility of the Cirque.

24th.—We left the camp for four days to climb as many peaks as we could in the time. The plan was to spend two nights in the Refuge of Tucquerouye, ascend the neighbouring mountains and then returning by the Val d’Arazas, famed for its beauty, to stop a night at the ” casa ” there, re-entering France by the Breche de Roland, and thence into the Cirque.

With much difficulty, owing to low clouds, we reached the Hourquette d’Allans. After a few hundred yards it became impossible to advance further as we could not see more than a yard or two ahead. At one time it looked as if we should have to spend the night out under a rock. The cold was intense and we had very few extra clothes : without a view of the Borne de Tucquerouye we were absolutely at sea. Suddenly the grey bank of clouds melted and flew into the upper air like spray off a gigantic wave. With a shout we dashed from our chilly retreat, and scrambled up an almost unclimbable scree slope at an amazing pace : there before us was the Borne de Tucquerouye like a colossal Cleopatra’s Needle, and round the corner to the left we hoped to view the Refuge. Alas for our hopes ! Before we had floundered to the top of the bank, which moved bodily with us each time we stepped forward, the clouds came down again. Determined not to be outdone, we bore to the left round a face of rock and cut steps up a glacier; this led into a couloir, which necessitated further step-cutting. We realised we were getting somewhere near the top, for a howling gale, such as one only meets close to a summit, was driving clouds past- us at a furious pace, screaming up the gully and tearing at the rucksacks. Using hands and feet we went straight up steep rock and ice, not bothering to traverse ; at last we discovered, with thankfulness, that we were climbing the right gully, about which we had been uncomfortably doubtful hitherto, for a glittering trail of sardine tins told its tale. After an interminable grind the supreme moment arrived when a square lump loomed up through the clouds, which was undeniably the refuge : with a final burst we reached the top and tumbled into the black interior.

What a banquet we might have had, had we been those pompous, pot-bellied people imagined by Rabelais, who ” live on nothing but wind, eat nothing but wind, and drink nothing but wind.” As it was, half-gassed by the smoke which belched forth from the fire, we choked down some toasted cheese and semolina.

25th.—We had intended to walk round the four-peak ridge, climbing the two Astazous, the Marbore and the Cylindre, but at six o’clock the clouds were still racing over the lake whence we had to draw our drinking water, 300 feet below us. The Refuge is built in a narrow gap in a long wall of rock. The steep couloir on the north side reaches up to the back wall and the ground, within a few yards of the front, drops precipitously to the lake. High columns of rock tower up on either side.

We got away by 10.30, having decided to climb only the Marbore and the Cylindre. Dropping down to the lake, we bore to the right, scrambling over big slabs of rock : here we found several roots of edelweiss. We continued climbing towards the head of the valley up a snow-slope, passing the Pics d’Astazou on our right. Then, having gained sufficient height, we crossed to the far side over a ghastly mile of scree. Here there was a glacier, leading to the foot of the Marbore, up which we did a series of zigzag traverses and arrived at what looked like an easy gully. All went well at first, though we very soon had to rope.up. The first few pitches were not difficult, though the rock, which seemed to be shale, was Very insecure, and came away in handfuls. We arrived at an almost unclimbable, overhanging wall up which we had to push the leader and then lever him up with our axes. We ourselves were none too secure, balanced on a sloping ledge of extremely loose scree. We did our best to anchor ourselves in case A. should fall, but as there was no rock to which we could belay ourselves, we had to dig our fingers and heels into the scree. After about half an hour, during which time showers of stones whistled past us from above, A. shouted to the middle man, to unrope himself. A seemingly interminable age followed, while we sat and watched the rope, now slowly disappearing, now remaining motionless for five minutes at a time. A.’s grunts got fainter and fainter till, having reached the end of the 100 feet rope, he told us to join him. I unroped, my brother attached himself, and went up, pulling pretty heavily. Last man in a climb is nearly always unpleasant, and I soon began to feel very sorry for myself, left behind with all the kit and no rope in a place where the slightest movement started the scree moving underneath me. It was disgustingly cold. The only sounds were the moaning of the wind and the occasional sharp rattle of falling stones : I knew by heart every detail of the valley below. I shifted my position once or twice to avoid the route most favoured by dislodged pieces of rock, but as each new position felt less secure than the previous one, I stopped searching for a quiet corner, and flattened myself as far as possible against the back wall. The stones, I thought, seemed to have a very long way to fall after they had hummed past my head and disappeared over the edge. After another eternity, a shout from above warned me that the rope was coming down : it ran over me and, catching it in one hand, I very gingerly attached the three rucksacks and the axes. Up they went, swinging well away from the cliff, returning to it just in time to foul an overhanging lump. For some time they stuck, and it looked as though either they would part company with the rope, or else the rock itself would descend on to me. Fortunately those up aloft decided to lower the impedimenta, and start again—this time with complete success. Now at last came my turn. The rope had several shots at finding me : it needed an accurate throw to reach me, hidden as I was and unable to move in any direction (except downwards). In the end I caught it, and with great difficulty, owing to numb fingers, tied on. To save time, I was instructed by directions, mainly inaudible, to come straight up. Thrice did I attempt to comply with these instructions : the first time I removed large chunks of rock with both hands and slid gently back to my starting point: the second time, I had almost succeeded when something gave and I dropped four or five feet and swung out on the rope, which mercifully held : the third time, feeling like a fly on a ceiling, gripping everything and anything with finger and toe, I managed to surmount that horrible, overhanging lump, and lay gasping like a fish out of water on the top (with feelings about as mixed as these metaphors). The rest of the hundred feet up to my companions was quite unpleasant enough, with a lot of exposed slab, and I was filled with unspeakable admiration at the achievement of the leader, who had done this without the aid of a rope. Our reunion, after several hours’ separation, was most hearty, and we all agreed there was a greater sanguinary element in that climb than in any other we had ever done.

An easy scramble ensued, which brought us to the summit in about half an hour, by the arete which we ought to have joined much earlier. Needless to say, we had missed the route described in the guide-book, and had come perforce by one which only a potential murderer would recommend. It was five o’clock when we reached the top (10,650 feet)—we must have taken about five and a half hours over our few hundred feet.

We sunned ourselves by the cairn and ate a belated lunch, looking out over a most marvellous view. Immediately below us yawned the gigantic chasm of the Cirque de Gavarnie. The horseshoe ridge all round it dropped almost sheer down into the cirque, with steep snow and scree slopes clinging to its terraced side. Beyond that and away to the south we seemed to see all Spain. We could certainly see as far as the central plateau, which lay like a blue wall, rising to a lofty mountain in the east. Thin bars of cloud split the distance up into layers of blue and white.

We could not afford to spend more than half an hour over lunch, and soon were slithering down towards the Cylindre on rust-red scree. Traversing the south side of this mountain, we reached a glacier, more icy than most we had hitherto met. We halted to decide whether we had sufficient time to climb the Cylindre. A. was lost in thought, conning the map, when the question was decided for him in an uncomfortably sudden manner : he lost his footing, sat down heavily and, clutching the map in one hand and his axe in the other, left us at a colossal speed. We watched his alarming descent, which consisted of a series of sharp cannons from one stone to another, interspersed by a few straight runs which accelerated his pace. His axe was useless as a brake and merely stirred up the snow in clouds behind him, like the slip-stream of an aeroplane taking off on a snowy day. We were tremendously relieved to see him get slowly to his feet on arrival at the bottom, for he had dropped about 300 feet in height, which represented a considerable distance on the surface of the glacier. We hastened to rejoin him, glissading cautiously, and arrived at the bottom without mishap, where we found that the only damages sustained were bruises and the permanent disfigurement of a pair of beautiful breeches of which he was veiy proud.

Fate having decided that we should not ascend the Cylindre, we skirted its base and climbed laboriously up a long scree valley, which ended in the Col de Mont Perdu (10,009 feet), whence we obtained an excellent view across the valley of the refuge, a black dot against the distant mountains, poised midway between an olive-green lake and the jagged crest of the ridge. To the south lay the Spanish hills, suffused with the llaming red and gold of sunset: the valleys were tilled with deep blue shadow. Low on the misty horizon hung the great primrose disc of a full moon.

We descended across two broad fields of neve and then down the precipitous glaciers, sometimes on the ice itself, sometimes on rock. We were very fortunate in finding the correct way down : any other route is impossible on account of the sheer face of rock and ice. By the time we had negotiated this descent and the bergschrund at the bottom the light was failing. Though the brilliant colours had faded, a pale, misty rose still clung to the peaks and the moon glittered high in the heavens. The glaciers we had left reflected the light in all the colours of the rainbow, and their columned steeps seemed to be encrusted with gems.

We crossed the valley again and skirting the lake arrived at the foot of the climb to the refuge in broad moonlight. Moon and stars and glaciers lay reflected in the black water. The refuge at the top was in deep shadow, except for the head of the Virgin, carved in the rock, which captured a stray moonbeam. The wonderful peace and quiet were in tremendous contrast to the stormy turbulence of the previous night.

26th.—We said good-bye to the Refuge, after having labelled and corked up what was left of the drinking water, and made our way over the Col de Mont Perdu. Dropping 1,000 feet to a lake, where we left our rucksacks, we began the ascent of Mont Perdu. The climb, which was up loose scree, took less than an hour. The view from the top was magnificent, Mont Perdu’s 11,000 feet overlooking all the neighbouring peaks. All northern Spain lay spread out before us, a dim blue line on the horizon marking the central plateau some 200 miles away. To the west rose the Cylindre, with its V-shaped belt of strata, and beyond it the glistening Marbore. The ridge bore right-handed in the form of a horseshoe and joined the two Astazous, thence running into the peaked wall which held the Refuge of Tuequerouye. The limestone Val d’Arazas which we were to enter, lay at our feet in a snake-like coil.

……………………….. After hours’ hard going we

reached the Saut de Gaulis, a sort of cirque at the head of the valley. Descending by iron spikes, we found ourselves in green fields. We followed the stream down, past caves with overhanging arches like cloisters, through a silver birch forest dappled with white light and dancing shadows and then into the twilight of pine woods. Out of these we emerged into flowery meadows—long avenues of silver birches—cows, pigs and human beings, the whole scene lit up by the rays of the setting sun. We secured beds at the low white inn known as the Casa di Ordesa.

28th.—Our route back to Gavarnie lay up the northern cliffs of the Val d’Arazas, through the Val di Salarus, thence up to and through the Breche de Roland, down into the Cirque de Gavarnie, and so home. A stiff climb through thick pine trees, then up open slopes covered with every kind of wild flower, brought us to the foot of the cliffs. The climb was fitted with iron crampons, so we were soon in the Val di Salarus. At the end of this we came in sight of the peaks above the Cirque : on the west the Taillon, then further east the ” fausse breche,” then the Breche de Roland, then the flattened Casque ; the ridge bearing right-handed led on to the glittering Marbore, the Cylindre and Mt. Perdu . . . A high bank of scree, cut in two by a horizontal band of snow, rose steeply to the foot of a long black wall of rock. A rectangular opening, said to have been made by Roland’s famous sword Durandal, formed the breche, and we made for this point up a precipice of balanced boulders. A howling gale was tearing through the gap when we arrived. The narrow walls towered up on each side to the racing clouds, the western one looking like a tall ship heeling over to the wind with bright snow piled up around its black bows.

We passed through the Breche (9,165 feet), and glissaded down the glaciers into the cirque. Rapidly losing height, we had magnificent views of the vast, perpendicular walls, which descended in terraces connected by steep bands of snow and scree : large black fissures appeared here and there like doorways to the underworld. This titanic masonry merged on the eastern side into the fantastically striated slopes of the Marbore, whence dashed the famous cascade, which falls 1,300 feet in three gigantic leaps. After falling some way the water is blown away in clouds like smoke, and on this particular evening the setting sun encircled it with a perfect rainbow.

That night a terrific thunderstorm burst ; the crashes of thunder went on reverberating in the deep valleys till drowned by the next peal. Rain poured through the tent. So continuous were the lightning flashes that we could have read books had we not been employed in holding the tent to the ground with hands and feet and trying at the same time to keep as much under the blankets as possible.

In the morning we emptied our boots of water, wrung out our clothes, squeezed the bread, and ate.

In the evening we left the mountains in cloud and rain.