Goyden Pot, Nidderdale

By H. Yates

Goyden Pot is situated in the dale of the Nidd north of the village of Lofthouse, 210 yards north of the farm called Limley, 22 miles from Harrogate.

Strictly speaking it is not a pot; it is simply a cave of engulfment into which the waters of the Nidd flow in flood time. During the drier months of the year the river sinks into its bed just above Manchester Holes, 400 yards further north of Goyden Pot, and can be followed a considerable distance underground in a southerly direction, by entering them. During flood times the water, besides sinking at Manchester Holes and in at least two minor sinks, plunges into the main entrance of Goyden, thunders into the Main Chamber via the Window, races along the main stream passage, and disappears at the end to reappear in the newly discovered lower stream passage down which one can follow it for about 120 yards to a walled-in pool, and only comes to light again at Lofthouse, about two miles south.

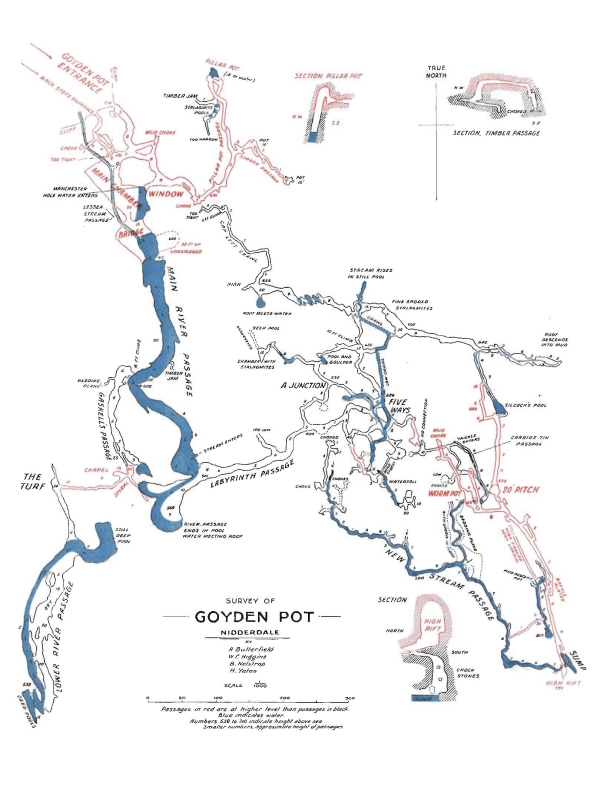

A close examination of the map will greatly help one to follow the underground meanderings of the Nidd, and the maze of passages formed by its tributary.

The first record that has been noticed of anyone exploring Goyden, is found in ChambersJournal,May5th,1888. The author of this article (unsigned, but known to have been by Mr. G. V. Gaskell of Chapel Allerton) describes his visit as a fourth exploration. and relates how he and a friend (the Captain and the Skipper) went into Goyden, climbed down a rope—fixed beyond the Bridge—into the Main Stream Passage, and followed it to what he considered to be the end. He must have kept to the right hand wall when the roof flattens out, otherwise, he could hardly have failed to find the Labyrinth Passage. (A lantern slide of a plan by the late S. W. Cuttriss shows that he and T. S. Booth were the first to enter the latter). On the return trip he describes how he found and explored a passage reached by climbing about 12 feet up the wall of the Main Passage. He describes it as sloping upwards and extending in a southerly direction to finish in a pool of extreme depth, near an almost circular shaft going up into obscurity.

Unfortunately the article gave no hint as to the position of this passage, neither as to its distance from the entrance nor on which side of the Main passage it was. Consequently the Gaskell find lay undisturbed for 43 years, to be rediscovered as shall be described later.

The next important event in Goyden’s history was the rediscovery of the Labyrinth Passage and the exploration of the Labyrinth by F. H. Barstow, R. F. Stobart and others, in June 1912, which resulted in a very useful map being published in the Y.R.C. Journal, No. 15 (1922). An accompanying article by the Editor, mentions a Y.R.C. meet at which at least 15 men invaded the Labyrinth in October, 1921, but, beyond the release from a timber jam of the direct route to Five Ways nothing new was found.

There is no record of any Y.R.C. men visiting Goyden for seven years (although a party of Gritstone men almost met with a catastrophe owing to the waterworks letting loose a quantity of compensation water and nearly drowning the party), until a detachment from the Wath Meet in 1928 went as far as “ Pillar Pot ” in the upper passages. A second visit in the same year unsuccessfully searched for Gaskell’s Passage. These two visits are mentioned in the Y.R.C. Journal, No. 18, p. 331.

On March 23rd, 1929, the Club held a Meet at Middlesmoor, at which only four men turned up, E. E. Roberts, C. E. Benson, G. C. Marshall and I. During the course of the day Goyden was visited and two of the party went as far as the Window and were so impressed by the appearance of the cave that they decided to come again in the near future.

Accordingly on June 16th of the same year a party consisting of W. V. Brown, J. Hilton, G. C. Marshall, E. E. Roberts and the writer entered the cave and went via Five Ways, Ten Foot Climb, and “ Chert Nodules,” to High Rift, the most southerly point of the cave then known. During this visit the nebulous chamber near the Twenty Foot Pitch, drawn with a dotted line in the Editor’s version of Barstow’s plan, was verified and furthermore was found to have a passage going out of it, which near its end gives a peep down into Carbide Tin Passage. This chamber has since been called “Worm Pot ” and the passage, “ Worm Drive” because a number of live earthworms have been found in that district, indicating a connection with the surface.

I have no notes about my next three visits, but if I remember correctly, the first party, A. Butterfield, myself, and about 20 friends and acquaintances met to explore a belfry a few yards south-west of Five Ways. Two ladders were taken in, one of the party climbed the belfry, fixed a ladder to the top, and the rest of the party followed. The chamber we reached was not a large one, and the party was, so something had to be done. We overflowed into a most inconspicuous little passage which after becoming still less conspicuous and then positively minute, opened out into a small chamber in which three men could sit comfortably, and in this chamber there was a pitch! As the bulk of the party was by this time down the ladder and preparing to make off, and as it would have been a good two hours job to disconnect the ladders from their belay and fix them up on our new pitch, we decided to call it a day and return some time in the near future to complete the job.

It was not long, and this time H. & W. Armstrong, A. Butterfield, B. Nelstrop and I, complete with two ladders and a suitable quantity of rope, made the second attack on this particular department of Goyden. As before, one man climbed the belfry and fixed the ladders, and the rest of the party came up with ease. The ladders were next rolled and made into parcels as flexible as possible. By dint of easing and coaxing they were brought through the tight and spikey crawl, and forced into the small chamber. The question of belay was answered by a hook made of rock, in exactly the right position and amply strong enough to hold the weight of a man and ladder. The pitch was found to be about 20 feet deep, but in the floor of the chamber in which one arrived was the top of the next pitch. The ladder, which had piled up was thrown down and a man followed. A glance at map will show where we came out! Disappointing—but all new stuff ! A short account of both this meet and the next is to be found in the Y.R.C. Joumal Vol.VI., p.77.

The latter occurred sometime in 1930. Butterfield, Nelstrop and self decided to force “Cap Left ” passage to a finish. We arrived at Cap Left via A junction and the Ten Foot Climb, as being probably an easier way than via Five Ways. Cap Left is about 50 yards of unadulterated crawling to a watersplash, in which one has to get wet, followed by about 20 yards of walking and crawling mixed. The passage finishes by sub-dividing, one branch too small to follow and the other stopped by a boulder choke.

We were all wet, through crawling past the watersplash, so we decided to go and have a look at the Twenty Foot Pot and see if we could find where the water, which drips from the roof, disappeared. We found that the water sinks into the stones a few yards down Carbide Tin Passage, but, more important still we found that an opening, marked down in 1929, could be entered at this point, and along it one could move in a westerly direction.

It started with a pool which if I remember rightly I negotiated fairly dryly (ever since I have got wet at this point). Shortly the route turned south and became rather more commodious, and soon the leading man was able to hear the roar of distant water. The morale of the party immediately mounted to hitherto unknown heights; it seemed almost certain that this was the Nidd we heard! I remember one member stating that should anything happen to turn us back before we witnessed the rushing waters, he would cry ! The noise became greater and on turning down a low “ side crawl ” we found ourselves in the roof of a passage about 8 feet high down which was flowing, not the Nidd, only a minor tributary of that river. Hopes were still high, for surely the stream must flow into the Nidd, which we believed was not very far away; accordingly we walked and crawled down stream for what afterwards was measured as being approximately 90 yards, past two tributaries, to a finish where the stream dropped 2 foot into a sump of “ unplumbed depth.” We amused ourselves by throwing stones into the sump in the hope of finding shallow water somewhere, but the splash always replied with the same deep bass boom!

We returned upstream, past the passage by which we had entered, now walking, now crawling, along stream-washed passage, loose boulder jams, pebble beds, past as many as seven passages on our right side, all less imposing than the one along which we crawled, a slow painful progression for 140 yards, finishing in a choked bedding plane which the survey shows to be within a few yards of Labyrinth Passage. The return journey was as uncomfortable as the journey there, but in due course we saw daylight—at the entrance.

On April 11th, 1931, four of us, Dean, Higgins, Nelstrop and I went down the bedding plane into New Stream Passage and along it to the Sump. Dean and I roped up, climbed round the corner, and gained a ledge a few feet above the Sump and south of it. From here it was possible to climb up a muddy rift about 30 feet directly above our heads, materially helped by two chock stones which tended to rotate when trodden on. As we climbed we seemed to be traversing back over the Sump and quite suddenly we found a firm floor under us and the rift, which had become a passage, becoming narrower. There was, however, next the roof a kind of miniature bedding plane along which we crawled with one leg in the crack until we suddenly found ourselves in a fairly large chamber. This turned out to be a passage of fair dimensions along which we walked at a good pace, passing a descent into a pot on our left-hand side, and we were delighted to find that the passage was growing larger. It seemed as if it would go for a long distance and we were eager to follow it to the end, but then came the thought of the other two of our party wet through, sitting on a wet stone in New Stream Passage, patiently (?) waiting for our return. We held a consultation, and decided just to go a bit further—it was fortunate that we did !—for about 20 yards further on we came into a chamber with water dripping from the roof, andaropehangingdowntheoppositewall. We were back again at the Twenty Foot Pot. It must be remembered that we thought our position was about 200 yards further west, that is, in the neighbourhood of the Nidd. We had been following an obvious tributary of the Nidd, downstream, and I think, had reasonable excuse for thinking that it would flow towards that river instead of flowing as it did, constantly getting further from the main stream. However, having re-assorted our ideas, we returned to the place from which we had entered the upper passages and shouted down to the people below to return to the Twenty Foot Pitch by the way they had come and we would meet them there.

[The Sump has recently been passed under drought conditions, but the passage beyond immediately closes to a mere crack.-EDITOR.]

We next visited the adjacent Mud Pot and followed the passage out of it, down which the water flows to another sump at the end. We thoroughly examined this pool and came to the conclusion that nothing could be done with it. Higgins, however, noticed a small “ rabbit-hole ” on the west side of this passage, about 8 feet up from the floor. He disappeared into this hole, head first, reappeared, reversed, and went in feet first, for this is the only way that this particular part of Goyden can be done. No one followed him down this rabbit-hole, but on questioning him afterwards about it we learned that the procedure is as follows.

You enter the rabbit-hole feet first and after one yard, you slide as gently as possible down a precipitous face, coated with mud, hanging on to a leaf of rock, and then climb back about 8 feet of muddy overhang into a second hole on the other side of the leaf. The rest is a crawl and you finish in New Stream Passage. Nothing more was done that day.

On May 3rd a goodly party assembled, but the heavens were unkind to us for they had chosen to loose a quantity of surplus water, and consequently Goyden was flooded. Some of the party, by dint of keeping well on the east wall, at the commencement, managed to get just below the bridge and could have gone on further. One important fact was learned on this occasion, namely, that in flood time the water enters the Main Chamber via the Window and not at all by the rock slopes down which one climbs.

It had been in our minds for a long time to make a detailed survey of Goyden, bringing up to date the plan made by Messrs. Barstow and Stobart, already referred to. Considering the short time which was taken over it, the Barstow-Stobart plan is a remarkably accurate piece of work, but considering the complexity of Goyden, we thought it deserved a more detailed and accurate map. Accordingly, a week after the flood, Butterfield and I armed ourselves with appropriate tackle and began surveying from the entrance. The whole of Main Chamber and Main Stream Passage and Labyrinth Passage as far as Five Ways was completed that week-end. The low sandy crawl going north from Labyrinth Passage was followed as far as was possible and we had to turn back within a few feet of running water (obviously the same water as that which enters the Nidd just north of Labyrinth Passage). As we were coming out of the Main Chamber, a few yards before we turned the left-hand corner which brings daylight to view, a small hole choked by a boulder was noticed in the floor. We wrestled a bit with the boulder, got it unstuck and rolled it away, and thus were able to descend a steep slope, at the bottom of which a short crawl started, ending in a short pitch, another horizontal passage, and—a fair sized stream. I am not at all certain if I have given the details of the descent into this stream correctly; the effect was most perplexing and we felt that there was some doubt whether we would be able to find our way out, consequently we did not spend much time in exploring, but concentrated our attentions on getting out. We experienced no difficulty but I feel sure that our route down and our route up again, differed considerably in places. .

On Saturday evening, May 30th, the same two with Roberts carried on the good work and explored further into this latest stream passage (since named Lesser Stream Passage). We were soon through the boulders and went first of all downstream to find out if, or where, it joined the Nidd. For the most part the passage was low and in at least one place the water very deep. In two places we experienced difficulty in keeping our lamps lit, owing to a full-blooded waterfall coming from the roof. Shortly after passing the last waterfall we suddenly found that we had come into a large chamber which seemed to extend indefinitely into the distance. Hopes and enthusiasm were high until somebody remarked that he recognised it as the beginning of Main Stream Passage. We had entered Main Stream Passage from underneath the bridge, by a passage of a fair size which had never been noticed, lying hidden behind a waterfall. Then, with considerable difficulty we followed Lesser Stream Passage, upstream. lt is not the usual type with smooth washed walls and pebbly floor; far from it, it is merely a track which can be followed with difficulty among falls of roof, finally subdividing into a submerged bedding plane from which the stream flows, and a high crack impossible to follow. It was midnight when we came out, and we were pleased to get into our sleeping bags, and listen to the rain which had started before we went underground, beating on to the roof of the tent. It had been arranged that the next morning we were to explore more carefully the New Stream Passage and particularly the Sump; but what is the use of arranging things beforehand, for the weather only comes and spoils all the plans? So the next day, instead of exploring Goyden, we just went a walk.

On July 5th, Butterfield, Nelstrop and self continued the survey, concentrating on Pool and Boulder and Five Ways districts. Higgins was occupied in showing the beauties of the cave to three other men who came with us. A word of warning will not be out of place; whoever takes it upon himself to camp at Goyden Pot at this time of the year, for his own sake should being some anti-midge preparation, though we found that the smoke from smouldering clothing was quite effective.

On July 26th, we again continued the survey and succeeded in completing all the cave below the Ten Foot Climb with the exception of the system of passages near the entrance of the pot, and of course Gaskell’s Passage, which had not then been discovered. While looking round among the rocks at the entrance for a suitable place to deposit a tin, Nelstrop made the very interesting discovery of an alternative way into Goyden, which might be useful in flood time. The hole had to be enlarged somewhat before we could get in, and even now it is a tight fit. Owing to the curious manner in which this passage descends, Nelstrop coined the name “ Back Steps Entrance,” which name it bears on the map.

While we had been diligently exploring and surveying the pot, another absolutely distinct party composed of men from the Pudsey Ramblers’ Club had become interested in Goyden. On August Bank Holiday, 1931, Messrs. G. N. Daley, K. Smith, and W. S. Farrar entered Goyden with the idea of searching for the passage entered by Gaskell in 1888. The Pudsey party passed it just as Gaskell himself and everyone else had done, and only noticed it on the return journey. They climbed the wall to it, and up the spiral 25 ft. climb and mud slope at the end (a horrible place well plastered with very wet mud and decaying vegetation), then up a 27 foot “ Spiral,” by both good luck and good management finding the small chamber which they named “ The Chapel.” The finding of the Chapel is the key to the whole situation; it is by no means obvious and entails a short traverse with a knee on each of two ledges, actually returning in the direction from which one has come. From the Chapel a winding passage leads to “ The Turf,” a vertical pitch of between 40 and 50 feet, 31 feet ladder climb, and it speaks very highly for the men of the Pudsey Club that they should tackle it with such a small party and just one rope. Farrar was lowered down and found himself in a fair-sized passage, a short distance from the Nidd. He followed the Nidd downstream but must have kept too much to the right-hand-wall, for apparently he completely, missed the dry passage running parallel to the stream, and finished lying on his back in water with his toes touching the roof, The return journey up the Turf seems to have given a great deal of trouble; two men working in a confined space have not much spare power to haul a third man up a 50 foot pitch over many points of friction. Eventually somehow or other they managed it, and with the rope coiled up two hot and tired men and one cold and shivering man made good speed towards the entrance.

Knowing nothing of the Pudsey discovery, Butterfield, Nelstrop and I on August 30th, again found ourselves in Goyden with the survey work in hand. A short time previously a cloud-burst had occurred in the district but no debris had been left to jam Goyden’s passages. There was evidence of the interesting fact that practically the whole of Goyden was subject to flooding (very interesting to any one down at the time), Anyhow, on the expedition in question, we had arranged previously to keep a sharp look-out ,along Main Stream Passage for Gaskell’s, and saw it about 12 feet above stream level on the right-hand bank. The passage starts in a most promising manner with plenty of room, for one to stand up, but after about 40 yards becomes much lower and eventually finishes in a steep decline down to a pool in which a fish was swimming about. Just before the decline, in the right wall of the passage is a low opening which leads to the belfry mentioned by Gaskell. At the time it looked a difficult but possible climb, and as the survey work had to be done, the belfry was left till another occasion. It is curious how Gaskell’s Passage had remained undisturbed since 1888 to be rediscovered in 1931, twice in the same month. The survey on this occasion included Cap Left Passage and the passage connecting it with Silcock’s Pool.

On 8th November, 1931, E. E. Roberts, Heys, and the regular Goyden party entered by Back Steps Entrance (as a torrent was going down the main hole for the third or fourth time), and went straight to Gaskell’s Passage. The Belfry was climbed without any trouble and we found a passage at the top leading to a small high chamber, from which one climbs the “spiral,” a curious, almost vertical “S” bend, well plastered with sloppy mud. Higgins and I followed the obvious continuation, a low narrow crawl which becomes higher but narrower, until we reached a point at which we deemed it advisable to stop. On returning to the top of the spiral, had we carried on with one knee on each of the two ledges, instead of going down, we should have come to the chamber named by the Pudsey Ramblers, “ The Chapel.”

In 1932 we continued our survey by two all-night shifts in February and March, but decided that on our next visit we would have a look at the system of passages which is a direct continuation of the entrance passage. Accordingly on March 20th, Higgins, Nelstrop and I, after an evening meal at Lofthouse, entered Goyden and went straight to the timber jam at the end of the entrance passage; it was surprising how easily we forced our way past the jam, it being all compressible material. We followed the passage thus reached to its end in a 15 foot pot with water of great clearness and considerable depth.

About three yards from this pot we found a low crawl along which we proceeded for some yards and eventually branched off along a still lower crawl to the left, which finished in a narrow passage descending and becoming at once higher but narrower. A trickle of water enters this passage and a few yards further on it becomes about 3 feet high, only one foot of which is of use, the other two being too narrow. Where this passage eventually finishes I don’t know; it is one of the most painful but most promising of Goyden’s passages and I will take off my hat to the man who eventually follows it to its conclusion. The fifteen foot pot we have named Pillar Pot because of its fine pillar of eroded stalactite, but this last passage which I have described defies naming, or at least the name which one might, give it defies printing; the point we stopped at is named the “ Sacrificial Stone.”

About mid-way between Pillar Pot and the timber jam is a chamber from which starts a low crawl, in mud, decayed vegetable matter, and fungus. This crawl finished uncomfortably in a shallow pot of about 4 ft. deep, but about half-way along its length is an aven, difficult to enter and difficult to climb. From the top of this aven is a passage leading round right-angle bends to the top of a 15 foot pot with no other exit.

Surveying was continued on April 23rd, at “ Break through possible” (I considered this to be a bad misnomer, but the Editor says it was broken through twice in one day in 1921), and then the upstream part of the New Stream Passage was tackled and completed though none of the side issues were surveyed nor, I think, will they ever be. We next surveyed the short piece of passage near Ten Foot Climb from which the stream flows which passes through Five Ways and gets into New Stream Passage.

On June 4th, the whole of the Pillar Pot system was surveyed, and the next day we made a tour of inspection during which High Rift in the far south was climbed about 20 feet, but no passage was found.

On September 24-25th, we had another nightshift to survey Gaskell’s Passage, and after a short search found and surveyed The Chapel and the winding passage leading to top of “ The Turf.” We rigged “ The Turf ” pitch with the bobbin ladder (a device composed of wooden bobbins threaded at regular intervals on a half-inch rope), and Higgins and Nelstrop descended and explored the passages beyond. On our way out Butterfield and I surveyed Lesser Stream Passage for about three quarters of its length (the rest on the map being merely guesswork) but absolutely failed to find the way by which we had first entered the passage, so had to retrace our steps to its junction with Main Stream Passage and return in the usual way.

The evening of October 1st was spent in surveying Back Steps Entrance, and on the following day Roberts turned up and we all made an excursion into the Gaskell area. We had two ladders and consequently were all able to get down to the lower Nidd which we surveyed, and, we hope, explored completely. It terminates amid fine rock scenery in two flooded joints. Jammed by flood waters in the roof of the second joint, as if done by expert miners, are two large and two small squared timbers. These are part of the debris of the crane once encumbering the entrance, and in some marvellous way havepassedthroughthesinkofMainStreamPassage. Another squared timber has passed Ten Foot Climb to near Silcock’s Pool .

The horizontal survey of Goyden was now completed but owing to some Y.R.C. men crying out for a few vertical readings, we felt it incumbent upon us to provide them with some, so in December Higgins, Nelstrop, Mariner and I, armed with plans and the Club aneroid, descended Goyden and took the first reading at point 9 of the survey (the hole down which we climbed when we discovered Lesser Stream Passage). Twelve readings were taken including two at point 9, one going in and one coming out, which showed a difference of 41 feet between the two readings, a deficiency which was divided out as accurately as possibly over the twelve readings, assuming an even fall in the barometer.

This aneroid survey will probably be inaccurate and I should like someone to re-survey it some time and check over our results. One obvious inaccuracy was in the relative heights of the place where the Nidd eventually disappears and the place at Lofthouse where it reappears, the difference being 33 feet according to our readings!

There is still work to do in Goyden for anyone thin and energetic enough to do it. There are several connections to be made. Pool and Boulder passage is waiting to be connected directly back to the main stream passage ; we have found what we consider to be the two ends but have been turned back in one case by a timber jam and in the other by a well of deep water. There is the connection by mining between Cap Passage and the entrance to be made. Labyrinth Passage should be connected with New Stream Passage and Carbide Tin Passage with the Five Ways System. A continuation of the low crawl in the Pillar Pot district will certainly yield interesting crawling if nothing else. There is still the large opening going east from just south of the Bridge in Main Chamber; all it needs is a 15 feet plank to bridge Main Stream Passage. There is also the barely accessible passage opening in the Chapel, which will probably need a wooden ladder. So we have left quitea lot for the next man.

Our thanks are due to Mr. Rose, chief resident engineer on the Bradford reservoir works, who took a lively interest in our work and assisted us enormously by keeping us well posted as to weather conditions, a most necessary factor in the exploration of Goyden Pot.

It is a fallacy that Goyden is all crawling ; it has its share, but I don’t think it is any worse than chunks of Gaping Ghyll, and it has the advantage of needing hardly any tackle.

There are two special features which ought to be mentioned as being peculiar to Goyden. Firstly, its chert nodules. Never have I seen in any other pot such an abundance of perfect specimens of these phenomena, some of them actually bridging the passages in which they are found. But a word of warning is necessary, many of them are rotten and absolutely unsuitable for belays.

The other special feature is the curious way in which the stalagmite formation is being eroded. It is obvious that at some time a drastic change has occurred which has stopped the natural building up of these stalagmites and has caused them to be worn away into the curious shapes in which they are found, still exhibiting the concentric lines of deposit in the same way that carved wood shows its grain. I think that this change has been brought about by the building of the farm above the cave, causing the acids from the manure to percolate through and eat away the stalaginite deposits. I have mentioned this theory to a chemist and he disagrees but does not submit any alternative theory.