Glimpse Of The Drakensberg

By G. S. Gowing.

For some time prior to my departure for an eighteen months’ stay in the Union of South Africa I had been busily reading the glowing accounts of mountain exploration in that country as set out in the Journal of the Mountain Club of South Africa. Full of enthusiasm, I had pictured climbs on Table Mountain, among the numerous rangesof the Cape Province, in the Drakensberg and even perhaps a visit to Mount Kenya or Kilimanjaro on the way home. But a very few weeks in Johannesburg, amid the monotonous scenery of the high Veldt, many miles from the nearest mountains, soon sufficed to dispel these dreams. The visit was not a holiday, time off was scarce, there was a lack of climbing companions which rendered any mountaineering prospects somewhat slender. So month after month passed and all I had seen of the mountains of South Africa were a few brief glimpses from the train between the Cape and the Rand.

Towards the end of my stay, however, at long last a companion arrived in the shape of a colleague on a short visit to Johannesburg, and one Thursday morning he dashed into my office and announced that he had the week-end free and “ what about some climbing? ” A short discussion followed and it was agreed to make a shot at the Drakensberg ; after which the rest of the day was spent in hasty preparations, the most important the finding of a trusting soul who would lend us a car to carry us over the three hundred odd miles of indifferent road separating the Rand from the best climbing centre in the Drakensberg. Thus the following morning saw me, just before dawn, picking my companion up at the Rand Club, complete with food, drink and a borrowed car.

Our destination was the Natal National Park in the Drakensberg. This range of mountains forms the eastern and south-eastern rim of the great interior plateau of South Africa and stretches from the Eastern Province to the northern Transvaal. The whole interior of the country is formed of ground some 5,000 to 6,000 feet above sea level and, just before this plateau falls away to the coastal region it lifts up to form a range of mountains, rising in places to 10,000 or 11,000 feet. The range as a whole can be followed for some 1,000 miles, but the part for which we were heading was that at which the boundaries of Natal, Basutoland, and the Orange Free State, all meet and which is actually the highest of the range.

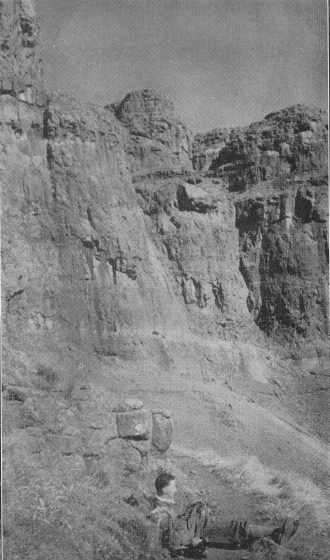

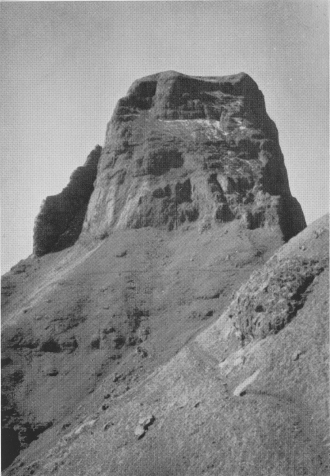

Our route in the car from Johannesburg lay through the Transvaal as far as the Vaal River, then through the Free State to Harrismith, after which we crossed the Drakensberg by a most appalling road over Oliver’s Hoek Pass and dropped down into the National Park, which lies at the foot of the Berg on the Natal side. As we drove up to the National Park Hostel, at which we were to stay, the geography of the mountains became apparent. The main range stretches eastwards and northwards in an almost unbroken escarpment of about 5,000 feet and the angle between the two directions forms a vast cirque of magnificent cliffs. On the Natal side the escarpment is precipitous, while on the Basutoland and Free State side the land slopes up more gently, the actual highest point in the range, Mont aux Sources, lying somewhat behind the edge. The cirque appears to have been formed by the cutting back of a river, the Tugela, which at present comes over a fall of 3,000 feet from the top of the Berg into the valley below. The whole country is igneous, the upper parts of the range being basalt, while the lower parts are volcanic sandstone, which forms strangely fretted ridges sloping down from the main escarpment.

Mont aux Sources itself, which is the highest point in the Union, is not a peak in the strict sense of the word, but merely the highest point in an area of high moorland and is, as mentioned above, some little distance back from the edge of the escarpment. The points usually climbed are spurs which, projecting into the skyline, form prominent objects in the view for miles around. The two of these which are nearest to the Hostel are 10,740 and 10,530 feet above sea level and are called the Sentinel and Beacon Buttress respectively. They lie together at one end of the cirque, while at the other is a series of towers of about the same height, composing what is called the Eastern Buttress. After some consultation we decided to have a shot at the Sentinel and accordingly set out from the Hostel at six the following morning—just before dawn, since it was almost mid-winter. Our climbing kit was, to say the least, sketchy, for neither of us had managed to raise even a pair of boots and we had, perforce, to do the whole trip in city shoes, an experience that the writer does not wish to repeat. In fact all the equipment we had was a folding lantern and it was lucky that we had this, for without it we should not have been able to get as far as we did. However, not to be deterred by such minor details, off we went. From the Hostel, the route follows a pony track all the way to the base of the Sentinel, a distance of about thirteen miles, rising some 5,500 feet, At first it lies along the valley of a tributary of the Tugela, through almost sub-tropical vegetation; and then climbs out on to a spur of the Berg, where there is nothing but the sparse grass of the veld. After reaching the main ridge, we contoured for what seemed endless miles on the Free State side of the escarpment, looking out to north-westwards over mile upon mile of bare brown rolling moorland.

It was past midday before we reached the base of the Sentinel, where only some 700 feet of easy rock separated us from the summit. And here comes the sad part of this tale, for we were both so completely out of training, so tired from our tramp, and in addition so affected by the altitude, that the rocks were too much for us. In our state and with our inadequate footgear we were obliged to allow ourselves to be repulsed by a little rock climb that would hardly be classified as “ difficult ” in the Lakes. We tried to console ourselves with the reflection that anyway the rocks were iced and had patches of snow on the stances ; they were, but had we been really fit we should have scarcely noticed it. So we gave it up and had some food and then I lazed and watched the view while my companion climbed, with the aid of a chain ladder conveniently erected in a gully, to the top of the Beacon Buttress and was rewarded by some photographs of the cirque. The view was certainly a grand one, for in the clear air one could see far away over the Free State into Zululand and pick out the kopjes around Ladysmith and Majuba.

The return journey was a slow and, with our dreadful shoes,a painful process. Dusk overtook us before we left the high level path, and for the last four hours we made full use of the lantern. Fortunately the air was still and the somewhat flimsy contraption served us better than it did on one memorable New Year’s Eve, when it failed miserably to light our way from Wasdale to Seatoller at midnight in a blizzard. Suffice it to tell that we reached the Hostel some fifteen hours after setting out, for the last half mile guided by a friendly Kaffir, having missed our way almost on the doorstep.

The following day, far too stiff for anything very energetic, we contented ourselves with strolling up the valley of the Tugela, to look at the end of the cirque. The clouds were lying low over the Drakensberg and we congratulated ourselves that we had not reserved the main expedition for the second day. The way up the valley was extraordinarily pleasant, leading as it did through dense patches of bush, filled with maidenhair ferns, cycads and other strange plants, these patches alternating with bare sandstone ridges covered with proteas and other kinds of shrubs. At the top of the valley the sandstone walls close in and the river runs through a narrow winding gorge, so nearly closed in overhead that its name, the Tugela Tunnel, could hardly be more appropriate. The river fills the gorge in places from side to side and wire cables had, at one time, been fixed over these pitches to allow the more adventurous tourists to pull themselves along, precariously suspended over the water in a “ bo’sun’s chair.” Now only the somewhat frayed lengths of cable remain, but by means of some ingenious engineering with these and sundry tree trunks found lying about, we were able to negotiate the gorge without a complete wetting in the ice-cold water of the Tugela. Altogether a trip distinctly reminiscent of pot-holing! After a brief stroll at the far end of the gorge we successfully made the return passage and wended our way back to the Hostel.

The following morning we set out for home, this time keeping east for a while in Natal, through Ladysmith, past Spion Kop and on to the main Johannesburg-Durban road at Majuba; then past the smoke of the Newcastle collieries and into the Transvaal at Volksrust. Next the long dreary run over the veldt, mile upon mile of dusty road, until at last We saw the low line of hills that marks the Witwatersrand, with little trails of smoke from the mines on the Reef, and so past the rattle and roar of the stamp batteries into Johannesburg and our trip was over.

The Mont aux Sources region of the Drakensberg is certainly a place worthy of a longer visit; as it is an ideal centre for mountain tramps. Although there are plenty of rock climbs mentioned in the guide book, we gained the impression that the rock is mostly rotten and in many places quite unjustifiable. But the scenery is good and hotel accommodation in the little thatched roundavels all that could be desired. Altogether we certainly suggest that any Yorkshire Ramblers visiting South Africa should not fail to include Mont aux Sources in their itinerary.