The Eisriesenwelt.

(The Giant Ice Cave of Austria)

By. J. W. Puttrell, F.R.G.S.

Austria is a perfect Elysium for all kinds of sport, but as a cave-man one envies the Austrians their large limestone areas, containing innumerable ice and stalactite caves of rare size and beauty.

On my way through Austria and Jugo-Slavia to the famous caves of Adelsberg, I saw probably the largest and finest ice cave in the world, and will endeavour to take you in imagination to and through the Eisriesenwelt (opened 1920) a wonderful undergound palace.

As a student of caverns, I had read works on glacières or freezing caverns, notably those written by Mr. E. S. Balch, of U.S.A., and by the Rev. G. F. Browne, M.A., but scarcely thought that I should ever see such strange natural phenomena. In the list of towns and villages to be visited was Werfen in Salzburg, a summer resort of repute, situated 1,720 ft. above sea level, on the left bank of the swift-flowing Salzach, 30 miles south of Salzburg. Our party of Yorkshiremen had travelled from Innsbruck, and it was after ten, cold and starless, when we stepped from the train at Werfen. Over the bridge and into the village we trudged with our heavy rucksacks, where at the Hotel Post mine host soon provided supper and homely accommodation. At six o’clock next morning we were astonished on looking out of the bedroom window to see a heavy fall of snow.

Had we been on a ski-ing expedition this Christmas weather would have been doubly welcomed, but we had arranged for the Eisriesenwelt that day, necessitating a climb of several thousand feet up the steep face of the Tennen opposite. The storm abated after breakfast, so we started off at 7.45, and crossed the Salzach higher up. It snowed slightly, but the outlook improved as we ascended through fir woods and green pastures, dotted with typical chalets. The sua now began to shine, and a grand view of the Schlossberg appeared, with Werfen far below to the left. This fortress of Hohenwerfen, 2,200 ft. above sea level, was built in 1076, about the same period as the Peak Castle, Derbyshire, immortalised by Sir Walter Scott in Peveril of the Peak, and like the latter, it would doubtless be impregnable in those days of primitive warfare.

After half-an-hour, we passed a picturesque klamm, or gorge, tremendously deep, spanned by a frail bridge; here are wooden gangways with handrails, to facilitate progress. Soon we reached a rast-hutte (3,433 ft.) where we were glad to stop and refresh ourselves. The herr spoke a little English, the result of an enforced stay in England during the war, and after gathering interesting news about the cave and its early explorers, we set off again by a red-marked route, passing a green-marked track from Tanneck, 1½ hours below. The steep path bent and doubled repeatedly to avoid precipice and rock-entanglement. Meanwhile the sky had grown very dark, and eventually a snowstorm burst upon us, blotting out the entire landscape for a time, but the sun soon asserted itself again, revealing the cave-hut in a clearing, and high above, the cold grey crags of the Tennengebirge. Evidently there had been several snowstorms lately, for all was covered in white, whilst icicles decorated the roof and fringed the tables outside the hut ; the inside was spotlessly clean and warm, and we feasted right royally on hot soup, meat and vegetables, an unexpected pleasure.

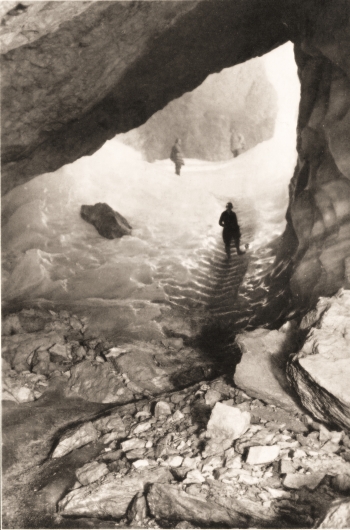

Having obtained our tickets for the cave, 3 schillings and 50 groschen, equal to 2S. 2d. in English money, we recommenced the climb under beetling cliffs and across deep ravines, with the guide, Lotter Moser. In thirty minutes the cave entrance was reached, an oval water-worn opening, like Thor’s Cave in the Manifold valley, about 100 ft. high and broad ; altitude, 5,436 feet. Unlike Thor’s Cave, however, the rock face continued several hundred feet up to the skyline and one wished time had allowed for an inspection of the region above the cave, to examine its physical features, for geologically the cave is most interesting. It belongs to the Tertiary period, when mighty rivers flowing from higher lands ruthlessly cut through the lower sedimentary rocks, leaving tell-tale passages and caves innumerable, and such gorges as the Salzach.

Acetylene lamps having been served out, the party clambered up the rock-strewn slope, then dipped downward about sixty feet, following a joint, which, narrowing, brought us to a palisaded gate, the real entrance to the cave. Gradually daylight faded, and the entrance chamber with its iced floor was seen to advantage, and beyond, beautiful frozen cascades, to us marvellous, but all this was nothing to the wonders yet to be revealed. We now ascended a steep arched chamber, over ice and scree, then by a wooden stairway skirted the nearly vertical edge of a frozen river, a novel sight. Here the guide climbed ahead behind a 40 ft. pinnacle, where with magnesium he displayed its rich emerald colour. Across to the right was another massive frozen cascade. Thus for two hours we explored grotto after grotto, gallery after gallery, with undiminished interest. Here for example is the Hymir Hall, a large place, with graceful ice curtains hanging from the roof; there, the resplendent Ice Chapel, and, hard by, a beautifully rippled icefall, which, on illumination, reminded me of the rich green tint of a choice Arizona stalactite in my own collection. Then in the Donard Dom is a pair of majestic ice pillars linking roof and floor, with a crystal stalactite between, a full yard long. Looking up, you see the cleft (replica of many others) through which water from the mountain top has drained for centuries, to be by King Frost so magically transformed. At the farther side are other ice pedestals and figures so wondrously fashioned by nature that even a Chantrey or a Michael Angelo would scarcely imitate them.

The Mork Hall, the largest grotto shown to visitors, is fittingly named after Alexander von Mork, the first man to explore the Eisriesenwelt, in 1913. This daring explorer (aged 27) unfortunately lost his life in the War, September 1914, and was buried in a soldier’s grave, far from home.

Ten years after, remembering his wish to be buried in the cave, his body was brought home, cremated, and the ashes placed in an urn and reverently deposited here. On arrival at the niche, we removed our hats in silent homage to the pioneer, and in memory of one who died for his country. Von Mork was no ordinary man, and his no ordinary task to initiate the exploration of this vast ice cave, and we who survive and enter into his labours, readily recognise his worth and work. The Mork Hall is 230 ft. long, less than half that of the first chamber in Gaping Ghyll, and no pillar supports the roof which reaches 165 ft., or 55 ft. higher than the Yorkshire pot-hole. When the brilliant magnesium light shone forth, the crystals in the dome scintillated like another Milky Way, myriad facets twinkling and reflecting the light from the darker background ; a starry effect, and a fine feature of the cave. The crossing of the Ice Sea, or Lake, with its glassy surface, was amusing. We linked together, arm in arm, and shuffled and slid across the smooth ice, first one, then another nearly tripping, but with the help of the steadier members of the party all ” landed ” safely on the other side.

Traversing an intervening passage provided a change of entertainment not so well relished by some, at the time. Before reaching the spot we heard a strange noise, which increased to a terrible roar as we approached. Naturally, we expected to see a rushing torrent or a miniature Niagara, but on entering the passage were nearly blown off our feet, and to make ‘ confusion worse confounded,’ all lights, save one, were extinguished. Instinctively we edged up to each other in the darkness and steered for that single point of light, which turned out to be an electric torch carried by the guide. As it happened I had a safety matchbox, but after creeping warily along, we reached a place where the harsh winds ceased, then relit our lamps and regained our composure. This peculiarity of ‘ Windy Corner ‘ is interesting, if only that it illustrates the varying local atmospheric conditions and pressure. My discovery, by the way, of the Cave Dale entrance to Peak Cavern, Castleton (a wind-hole connection with the Great Chamber, 150 ft. below) was through a knowledge of this simple law of nature.

The party now examined the ice walls, here coated with powdery snow or hoar frost, as though coarse salt had been sprinkled; doubtless this disintegration is caused by the sand-blasting action of fierce air currents, which are seasonal in their nature, and derive their force and direction from alternations of temperature. Throughout the winter the wind sweeps into the cavern with hurricane force, and in summer, owing to the rise in temperature, it rushes out. Another grotto which one naturally called the ‘ Crystal Grotto,’ was the limit of our journey. ” Beyond,” said the guide, ” are long stretches (18 miles) of galleries, etc., greater than any you have ever seen.” It was tantalising that time and circumstances did not permit further investigation. This Crystal Grotto exhibited a rare cluster of perfectly clear stalagmites, Indian club shape, the whole resembling a glass and china department of a large shop, and when the guide, Moser, placed his light behind the glassy pillars, it refracted most dazzingly through and on to the wall beyond. Looking distantly to the right, across an abyss, there were taller columns, exquisite in form, and ghostly white.

Reluctantly we began the return journey by another route, and I was glad that this did not exclude ‘ Windy Corner.’ In passing I tried my best to maintain a light, but alas, ‘ Boreas rude ‘ was against me.

At the entrance of the cave we enjoyed the splendour of day and the alpine breeze, then, further refreshed by a cup of tea, and still full of the wonders of the nether ice world, we made tracks for Werfen, arriving at the Hotel Post at dusk.

The public owes much to the efforts of Dr. E. Angermayer of Salzburg, and other noted Austrian explorers. For example, we climbed one of the great ice banks by a stairway in five or six minutes, but Dr. Angermayer, on his first ascent, succeeded only after eight laborious hours of step-cutting.

[Martel, in Spelnnca 1930, refers to this cave as the greatest cavern and natural ice-cave in Europe, 27 km. = 17 miles of known galleries. How far this figure of the proprietors is dependent on survey is not stated.—Ed.]