June Days In Ross And Skye

By D. L. Reed

Alpha and Beta went up by road ; Gamma followed two days later to be met somewhere on the line between Inverness and Achnasheen. ” No one,” a commercial gentleman informed him, ” no one north of Aberdeen cares much about the time,” a statement borne out later by a roadmender near Little Loch Broom. He asked the time ; we told him. ” Will that be summer time ? ” he said.

The train was a couple of hours late at Inverness ; the others, half an hour late on schedule, chased an imaginary train all the way from the Cromarty Firth to Achnasheen and seemed to be getting further behind all the time. At last they found a porter who convinced them that the train they had been told about at different stations was going the other way.

The car was well provisioned, four dozen oranges, one Dutch cheese, ten packets of chocolate of ten different varieties, two pots of honey, besides commoner comestibles. We sampled them all on the way to Loch Maree. Here, or to be exact at Kinlochewe, we pioneered by staying at the Manse instead of the hotel. Virtue had its own reward, the minister claimed relationship with Campbell of Sligachan and we were made exceedingly comfortable. But it was at the hotel we heard how a stag came down off the moor, charged the clothes line and disappeared on to the Heights of Kinlochewe, bearing Mistress Campbell’s red flannel petticoat on its antlers.

Loch Maree is worthy of the Highlands, well set with wooded islands, Slioch on one side, Ben Eay on the other, notable at one time for the visits of Queen Victoria, later for botulism and at all times for midges.

Mist hung around the Central Buttress of Ben Eay (Bheinn Eighe) when we approached, mist that hid the distant view but gave the climb enchantment ; we felt that we had got value for our four hundred miles from Yorkshire, for we saw not a single cairn or nail scratch. The angle of the rocks was a magnificent approximation to the vertical; Gamma remembers this (and having the remains of a boil dressed before roping), the dark sandstone of the lower half of the climb, a broad, sloping, grassy terrace dividing it from the light grey quartzite above, and Alpha removing jacket and pull-over to tackle a narrow chimney. He remembers also a grand scree run of fifteen hundred feet or so on the descent.

We had some stirring descents this June, this and a gully on An Teallach, Dubh na da Bheinn in mist and a gale o’ wind, interminable scree on Blaven and a scamper from the foot of Collie’s on Alasdair down into Glen Brittle.

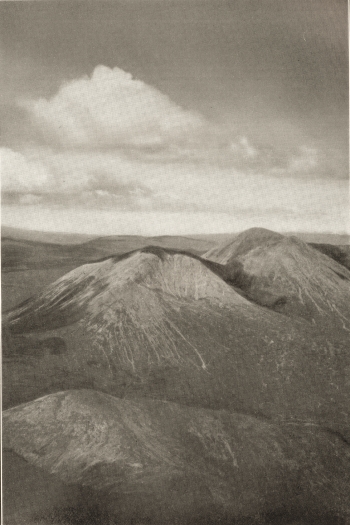

Next day Ben Liathach, that sets a worthy ridge between Ben Eay and the head of Loch Torridon, three thousand four hundred feet and hard going—some startling precipices on the north side, the top sometimes quartzite, sometimes sandstone weathered into curious ” fingers ” which looked like stacks of gargantuan chocolate biscuits, appealing sight to Alpha.

Fifty miles of narrow roads along Loch Maree, past Gairloch, Gruinard Bay and only just past a fishing party who had laid out a salmon on the road and were standing around it in solemn admiration, brought us to Little Loch Broom and a starting point for An Teallach, a complicated mass which showed its rocky summits for a moment before retiring into the clouds. We finished the honey and set off at two p.m., soon to meet mist and a cold wind. There was a quantity of sundew on that moor and a brilliant red heath grew in patches between the rounded grey quartzite stones that made up the last five thousand feet of scree—we thought it more at the time but five thousand is a reasoned estimate. The descent was worth the labour. Alpha found a snow gully, a thousand feet and perilously steep, rocks unclimbable on the right, slimy and loose on the left. We climbed into it and became a little frightened—no rope and would a pointed stone be as good a brake as an ice-axe ? Alpha commenced to kick steps, Gamma followed slowly wondering how he could steer for the side if he came off ; Beta thought about it. Step after step Gamma followed Alpha, till, at a place where the slope eased momentarily they turned round to look for Beta and were horrified to see him descending crouched instead of erect; he had no snowcraft. Alpha and Gamma felt that if once he got his weight on his bottom instead of his heels their job would make slip fielding to Macdonald look like catching shuttlecocks in a drawing room. Then Alpha tried a short standing glissade towards the haven of a rock wedged in the n”u .111-1 Eeti hed u|> under control in a species of Christiania, I” In I grcal joy. Thereat Beta was forgotten, the other two finding they could perform rudimentary Stems and Christies did the last five hundred feet of snow in dazzling style, a magnificent run, climbed back and did it again before Beta had descended by way of the rocks.

Heavy rain came on before we reached the car ; four hours we had on An Teallach, crowded ones ! It may have been because we were late and wet, or because the cars ahead were moving slowly, or perhaps the glissading had gone to our heads ; we were held up on the way back behind two big Bentleys.

We cruised off the next day through Achnasheen to Loch Carron over Strome Ferry, and over the Kyle to Kyleakin, and so by Broadford and Sligachan to Glen Brittle. Returning from the island we crossed Dornie Ferry as well, completing the ” three ferries ride.” Of these crossings it is said that whereas the ferrymen at one are incompetent and at the next uncivil, those at the third are invariably intoxicated. We had one or two landmarks to pick up, Sligachan of course— (presumptuous no doubt to criticise such a delectable hotel but the price of shandy really is out of proportion—” Do you wish beer, or do you wish ginger beer, or do you wish both ? ” said the meticulous waitress and charged according). Then the track to the Red Burn and Nan Gillean ; the house of the doctor whose maid knew no answer but ” Coo.” ” Is the doctor in ? ” ” Coo ! ” ” Is this the doctor’s house ? ” ” Coo ? ” ” Where is the doctor ? ” ” Coo . . .”

The place where W. casually drove his car off the road into the ditch, and the ditch showing its scars a year after the event ….

So we bumped down the Glen Brittle track ; the Coolin ridge was clear, I remember, and down in the glen the bank of gorse justified by its display our ministrations of the year before. We brought up at Mary Campbell’s ; she issued forth with greeting and behind came the hospitable aroma of the kitchen. We enquired of her brother, Ewan Campbell. Immediately, without word spoken, almost before the end of the question, some subtle change in atmosphere made us aware all was not well; Ewan Campbell was dead, he died in the winter 1930-31.

Having stayed once chez Mary there is pleasure in returning ; one arrives just in time for tea, always, and the welcome is real. Gaily we balance sponges on the tea-pots in the bedroom, toss with pennies for the right of sleeping alone, speculate how many men will be sharing the other bed. The holes in the sitting room floor are not mended, nor is the bed there made ; we might be returning from a day at the far end of the ridge instead of from a year in Yorkshire.

A dull morning and we set out late as usual. (Why is one always late at Glen Brittle ? Because it doesn’t matter what time you get back. Because there is no darkness). Over the moor and round the point we went, Gars Bheinn on the left, Soay on the right—the fishers there have deerskin rugs but there were never any deer on Soay—so into Coruisk. We climbed a thousand feet up the Dubh ridge before the weather broke, strong wind and driving mist ; we quickened our pace, the wind freshened, the mist got home at knees and shoulders. At first the chill moisture invigorated, and we raced up the easy slabs to Dubh Beag. There are a couple of pitches down from the summit of Dubh Beag ; we found them and got down but the rope was sodden and heavy, the troops sodden and tired of leaning against the wind. We chased up Dubh Mor, tiring a little, Gamma wondering how long he could sustain the pace, how many times we should take the wrong ridge off, how many times we should have to retrace our steps before attaining Dubh na da Bheinn. We reached the summit of Dubh na da Bheinn, with its indeterminate surroundings made more bewildering by the clouds which drove through our breeches. We remembered that other time, the first, light mist only and hours spent looking for the Tearlach-Dubh gap, till we found an exposed basalt dyke whose photograph was in the guidebook—its name would tell us where we were—turning the limp pages to find the title ” Vertical Face of Gabbro determined by a Basalt Dyke,” then returning dejected to Dubh na da Bheinn.

We aimed now at Coire a Ghrunnda. Any other Coire would land us at the wrong side of the ridge, further away from home It was important to find Coire a Ghrunnda ; visibility was twenty yards, every direction looked alike, but Alpha and Beta found it, Gamma fell off a crag right into it, only a six foot fall but clear through the air, lasting long enough to make him very frightened. Shortly we found the lochan, walked across it without getting wetter, slid down the slabs to the lower corrie and hastened out across the moor. The mist had crept down within four hundred feet of sea level. Our fellow lodgers, the Breezy Colonel and the Silent Scot met us at the door with a whisky flask. Eight hours, the last four spent right on the top line of exertion.

Thereafter it rained for thirty-six hours. Amusements got more strenuous as time went on; a crossword in three dimensions was constructed by Alpha and Gamma, solved by Beta ; Beta and Alpha found the names of the nine daughters of the nine mothers who each bought as many feet of cloth as it cost farthings a foot. After Gamma had found to his own satisfaction the locus of the mid points of parallel chords of a parabola the weather gave in.

As the clouds cleared we climbed the Cioch Direct to emerge joyfully into sunshine on the summit. We thanked God for gabbro and tricounis and double cotton cantoon[1]. We looked regretfully at the routes on the Cioch Upper Buttress for it was too late to tackle them, so we had to content ourselves by skating about down the great slab that looks so formidable to one who has not made a practical determination of the coefficient of friction of gabbro.

To have the weather clear up as one climbs is one of the delights of the Coolin. One starts beneath a grey sky wondering how long he will keep dry, climbs up into the mist, sees it moving, sees rifts, ” the clinging vapour slopes athwart the glen,” concentrates on a difficult pitch, belays at the top and behold the mist is gone ! Rum is there and Muck and Eigg, Soay and Canna, Loch Brittle shimmers in the sun, and riding the western sky are the Uists, Benbecula and Mingulay.

The traverse of Garbh-Bheinn, Clach Glas and Blaven was an excuse for dinner at Sligachan. More than a dinner, it was a brief return to civilisation after a week in the cottage and on the hills, a hearty feed after the long tramp down Glen Sligachan from the foot of Blaven. Taking Clach Glas from the north as we did one does not get the best out of the ” Impostor.” We left the summit by an ordinary piece of ridge work, and not until we had skirted his slabby side and looked back did we realise what a truly terrifying knife edge he seems from the right point.

After dinner we drove quietly back to Glen Brittle, Alpha and Beta recalling their dangerous, sleepy-headed drive a year before after having done the ridge from south to north during the hottest day of the summer.

We spent another day or two on Sron na Ciche and Alasdair, then left for Glencoe. We found the road down Loch Linnhe handed over to a happy band who had torn it up and made mud pies of it. Accordingly we proceeded from Fort William to Ballachulish in a series of front wheel skids, reminiscent of a ski-ing party in the Pennines where an unsuccessful manoeuvre may deposit the performer in a hedge or ditch. Up Glencoe we went, first on the foundation, then on the surface of the new road. We spent the night at Kings-house and the next morning set out for Buchaille Etive.

Votes were cast ; Gamma because of his idleness in Skye was chosen to lead Crowberry. Steep, firm rock, very pleasingly led to the little terrace before the piece de resistance. (Why is there no suitable English phrase for this sort of thing ? How impoverished ” bad corner ” sounds, compared with ” mauvais pas.”) Gamma, looking at the direct way edged towards the easier but less virtuous route up the side of the gully. Alpha pulled him back and chivvied him out on to the face of the precipice. There he stood, his toes firm in two adequate ledges, his hands resting on a smooth sloping mantelshelf, his heels poised, or so it seemed, directly over the bar of the Kingshouse Hotel.

” The longer I remain, the more comfortable I feel and the less chance I see of getting any further.”

Reprieve was granted, Alpha took his place ; “I agree,” said Alpha. Some minutes later the rope moving out, slowly, showed that the leader had changed his mind. Gamma brought the third up, recited a short prayer to Arthur Beale and edged out on to the cliff. Somewhat to his surprise he reached the mantelshelf, stood there as best he could and found it much more uncomfortable than the stance below. There was, however, a finger hold just out of reach that should make all secure. He reached for it, stretched for it, extended every muscle to get it, got there and found it slimy.

Later he joined Alpha, found him standing on wet sloping rock, the rope hitched over a microscopic protuberance behind.

” Now you’re here you might just hold the rope over that hitch in case Beta comes off,” thus Alpha. Doing so Gamma had time for reflection.

We did some notable eating at Kingshouse that night; dinner was lavish, but we were not going to be defeated by it after conquering Crowberry. Alpha led again in magnificent style. Post-prandial entertainment was on a royal scale befitting the place : internecine strife between two navvies on the road outside, in the drawing room a disquisition from a gentleman who that day had seen a snow avalanche as he motored up from the south. There was no mistaking it, he’d done a great deal of ski-ing at Miirren (his accent was perfect), and he was just as sun: of the avalanche as he was that the ending of all Russian genitives was spelt ” obb ” and pronounced ” of.”

Home next day, by the road already familiar, so few are roads in the Highlands, Bridge of Orchy, Tyndrum, Crianlarich, Callander, Edinburgh. Then, for it would be unseemly to spend the last day without seeing something new, we fetched a compass through the Border Country, by Selkirk, Hawick and by Note o’ the Gate to that lonely region at the head of the North Tyne. Down the Tyne and across at Corbridge, across the Derwent near Castleside, the Wear at Witton-le-Wear till, little by little, we left the hills for that smoky desolation that invests the Tees.

1. D.C.C. a tough windproof fabric used in the manufacture of Billingham type breeches.