Mountain and Sea – IV

By M. Botterill

Over ten years have passed, since the publication of the last article with this title. Many changes occur in ten years. Molly, 10 ton yawl, remains always ready to sail whenever her skipper wishes to explore some Western Isle, but alas, the years have taken toll of her crew.

For Skipper, some of the novelty has gone : gone too is that freshness of outlook which marks the novitiate stage, for which freshness experience will forgive the novice his faults and overstatements. Perhaps in rock-climbing I find the change most marked : experience cannot make up for diminished muscle and increased weight.

But since Mountain and Sea be both of them exacting mistresses, requiring ardent wooing, so too they will repay the devotee by displaying ever fresh charms and exciting unfailing interest until physical disability dulls the senses, and age leaves but the memory of the larger freedom won in youth.

With the years comes a useful caution enabling one to avoid many arduous and trying times. It is not usually the old hand who spends a night out on some precarious mountain ledge ; but at sea one has still to stand up to an occasional dusting, though experience render such occasions rarer.

The defection of Molly’s auxiliary engine at the end of 1934 has led to a recrudescence of one evil, i.e., nights-out at sea. As yet we have not replaced that undependable piece of ironmongery and as a result have been welcomed like the prodigal son, by the die-hards who won’t have an engine at any price.

In 1928 I climbed Cir Mhor with Rimmer by the Western Stone Shoot—” the climbing is more treacherous than difficult “—and also Caisteal Abhail by the Witch’s Step. Ben More in Mull was added to the bag in that year.

1929 was marked by constant rain and gales. Several abortive attempts were made on the Coolin. I had one good day with Cooper on the Dubhs and Alastair via the Gap, returning clown the Sgumain Ridge. Looking back over the years I have had bad luck with these hills. Out of seven days to be devoted to climbing there, on three it would be impossible to make a start; on two we would start and be turned back by heavy rain before reaching 1,500 feet ; on the other two, one would allow us to reach the summit and only get off with the greatest difficulty, and only the remaining one would be a real good mountain day.

1930.—Stormy spring weather with northerly gales caused Molly to arrive late at Fort William for the Club Meet. But we arrived in time to collect Fred Booth as crew and almost to lose other members who came to visit Molly in a sinking punt. We explored hills on Rum and S. Uist, Booth bringing luck in the way of weather.

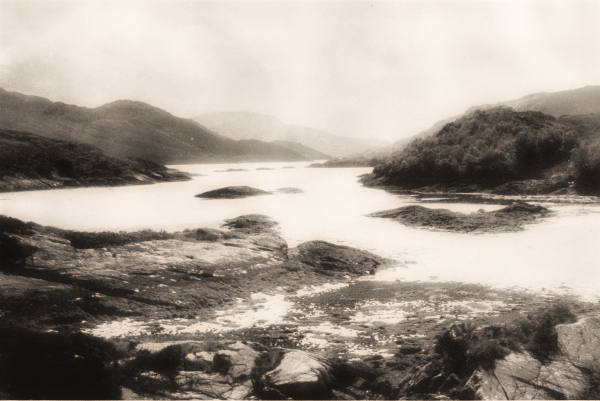

Later, more of the Outer Isles were visited and we even climbed the 1,500 feet of Benbecula, an otherwise flat island most of whose surface is water. A landing was effected on the difficult and extraordinary Shiant Isles, followed by a run up Loch Seaforth (between Lewis and Harris) in a gorgeous and unforgettable sunset. It is one of the most beautiful of the Scottish lochs and is only rarely visited.

Unsettled weather set in and so it was decided to take a run to France. The bad weather followed us all the way south until we reached Milford Haven on July 13th, some 14 days later than intended.

15th July, 1930 (St. Swithin’s).—Molly made 22 sea miles of the 100 which separate Milford Haven from Land’s End, beating under double reef until the wind became so violent no headway was possible, and we ran back in a gale with heavy rain, the dinghy sunk and towing under water.

17th July, 1930.—A second attempt was made under similar conditions and we were glad to reach the Haven again after getting only 10 sea miles south. The bad weather was so consistent I went home for a week and heard that it was very fine in Scotland !

Heavy winds still prevailed on my return to the yacht and we put in time with a run up the river Clwyd. We learned later that whilst we were having tea on the Molly in a sheltered reach, two people were drowned just round the bend where the full force of the wind was unobstructed.

30th July, 1930.—-Weather quietening down all day ; we were a month behind schedule ! It was now or never. At 9 p.m. we put out to sea, finding a light breeze against us, and a heavy sea running still. Progress was slow.

31st July, 1930.—Sea had subsided and the wind had gone lighter still. Barometer down 2 points this day and a nasty haze coming on towards evening. In the night we thought we detected the glow of some seaport on the Cornish coast.

1st August, 1930.—Barometer down a further 3 points, a dull menacing day and very poor visibility ! Skipper having foolishly taken coffee made from essence, when no milk was available, fell very ill. It’s poison ! In the early afternoon we sighted Pendeen Point, making our position some 10 miles north of it. We had made 80 miles, with only some 20 miles to go to round Lands End. The wind was freshening and unless its direction changed I knew we could not face it. A big sea got up and a mizzen stay carried away, but we repaired it. At 5 p.m. in a howling wind and with the sea rising all the time we had to take in our mainsail and heave-to.

There was only 10 miles to go to get into the English Channel but it was impossible. I decided to run back the 90 miles to South Wales and gave the necessary instructions from my berth, where I had been wedged in with cushions after a dose of medicine. I slept through a terrible night, having told them to keep watch until 6 a.m. when I was to be awakened. Molly sailed herself with only a small mizzen and a small jib and required no one at the tiller.

2nd August, 1930.—I took over at 6 a.m., having partially recovered, and sent crew below to doze. We were all hungry but even boiling a kettle could not be done in that evil sea. Water sluiced about the cabin. Cook managed to make some sardine sandwiches and put them in a watertight tin. It was great fun trying to get one out and eat it before a sea got it.

9 a.m.—Sighted Lundy Island, N.E. 10 miles, so I changed to port tack. We had made good 50 miles, without attention to the tiller. I judged that we should make 5 knots and therefore arrive back at the haven by 5 p.m., but this last 40 miles took us over some bad shallows so that the seas there were really dangerous. I dodged them all I knew (it’s a game I find very fascinating), but a nasty one came in aft and a large part went straight down into the cabin carrying the wet carpet forward and completely wrecking our last sandwiches. At 5 p.m. we entered the Haven, which seemed incredibly peaceful after 70 hours’ storm-tossing. After a square meal we slept the clock into its second round !

The French trip was abandoned and instead we ran Molly to Port Dinlleyn (Carnarvon Bay) where Burrow and Rimmer were holiday-making. Even there evil wind pursued Molly. On the 18th a bridge party came on to Molly but could not return—even the boatman would not put out to fetch them to their sorrowing wives until 7 a.m. next day ! I draw a veil over their sufferings ; an anchored boat is worse than one under way.

Again on the 20th Skipper entertained a party to tea, but on taking them off was himself unable to return, although Molly lay near the shore. I left her at anchor (not without misgiving), accepting dry clothes and a bed ashore. It was a terrible night; a yacht with six aboard was lost off Fowey. Molly rode safely all night without anyone aboard. And so by September of this stormy year Molly arrived at Glasson Dock and lay afloat all winter where Skipper could get to her.

In 1931 and 1932 we found that in sailing from Glasson for Scotland in spring, we usually had adverse northerly winds, and in returning in autumn adverse southerly winds, giving cruises more adventurous than pleasant. I skip new anchorages made in the north and fresh hills climbed, and visits to Northern Ireland, and come to the trip south in 1932, which must rank as our most unlucky year.

We lost main anchor and chain at Oban, our dinghy off the Chicken Rock, I.O.M. We had sails torn to ribbons in the Irish Sea and the vessel out of command all night—once on her beam ends—and finished by grounding in the Lune and nearly losing the yacht and ourselves. Jack Wright and Skipper sailed her off, water-logged, and beached her at Glasson. After these unhappy experiences I decided that if once I got back to Scottish waters safely I should want a lot to persuade me to look at the Irish Sea again.

In 1933-4 we sailed north and resumed lovely cruising again in Scottish waters (rain or no rain !), making many new anchorages, and visiting Ruttledge on his Island of Gometra. We even entered Loch Teacuis (Morven)—a rock strewn firth into which very few yachts have ever penetrated. At the end of 1934 a big-end made a complete end of the engine.

In 1936 Molly sailed north to Loch Laxford (nearly at Cape Wrath). One or two nights out could have been avoided had we had an engine. The year was marked by splendid weather up north, much better than in Northern England. In particular I remember a splendid view from the summit of Busbheinn (also called Bay-ish-ven and Bairsh-ven). This is an outlier of the Torridon Group and we could see the whole sea-way back to Laxford and pick out the various Lochs in which we had anchored.

Sutherland was suffering from drought, so much so that the streams were so reduced as to prevent the salmon running upstream for spawning. They were jumping out of the sea noisily enough to disturb our night’s rest. I met an old Scot ashore. ” Ye’re off yon wee yawl ? ” he questioned. I pleaded guilty. ” See the way the salmon’s jumping all round yer boat—you should be gettin’ some,” said he. ” But we haven’t a licence,” said I. ” It’s no a licence ye’re wantin’ ” said he, ” it’s a net! “

1937 by contrast was very wet up north. Such wet spells serve to enhance the wonder of the odd fine days that do occur and we had such a day basking on the Scuir of Eigg with marvellous visibility—the mountains of the mainland—the Coolins of Skye—the Chain of the Outer Isles with their hills—and the near-by range of hills on the Island of Rum.

Round about August ist we experienced a delightful spell of weather, but almost without wind, so Molly could not get far. I’m afraid the yachtsman takes a lot of suiting ! Almost our last ” sail ” was a very slow ” row ” to Crinan in one of those most wonderful Highland sunsets. The water was so still that it gave us perfect reflection of the mauve hills of Mull and the black-purple of Scarba and Jura, whilst through the Gulf of Coirebhreacken streamed the orange light over the Atlantic, where the sun had set. The middle distance was dotted with islands and islets var}dng in shade and colour as the sunset glow caught them. Only in Scottish waters have I seen such vivid colouring—a colouring whose very vividness blends with and is part of the seascape, producing a harmony which no artist can depict. And so with this lovely picture in mind I left Molly to hibernate.