THADENTSONYANA BASUTOLAND, EASTER, 1951

By C. W. Jorgensen

During a restful week-end on the coast near Durban, the talk went on about high mountains in South Africa. My host, Desmond Watkins of the Natal Mountaineering Club, outlined an expedition into Basutoland which would take four to five days on foot. In 1949, he, Barry Anderson – a surveyor – and a small party surveyed the Makheke and established that peak as the highest in Basutoland (11,360 feet). This computation was accepted by the South Africa Survey Department last year. During later expeditions to Basutoland a still higher peak was thought to exist and the object of our proposed journey was to locate this and by survey establish its actual height. As the Drakensberg Escarpment is less than 11,000 feet generally, Basutoland can in any case claim the highest hills in Southern Africa, apart from Kilimanjaro and Mt. Kenya.

Imagine unsurveyed heights only 100 miles from Durban as the crow flies. I was only too pleased to join and when the final party met on the Thurdsay before Easter it consisted of Watkins as leader, with Anderson assisted by Roy Goodwin as surveyors. The remainder to act as cooks, bottlewashers and scarecrows.

About 95 miles from Durban we branched off the main Johannesburg road at Nottingham Road Junction where we left the tarmac and continued on a secondary road with earth surface. Taking into account that there are only 2½ million white people altogether in the Union the road system is good. Off the beaten track one finds roads with tolerable surfaces over which one can travel fairly fast and get to really remote places.

To give us the most of the views en route, we camped early that evening on the Amanzamyana (River of the Black Waters) by the road side. The views we enjoyed next morning certainly were worth waiting for. The road rises to 6,200 feet in one place before dropping into the Loteni valley. The Drakensberg mountains guarding the approaches to Basutoland looked fine. After branching up theUmkomaas river valley, we finished our 63 miles of secondary road motoring at the last trading station. Here we left the cars at 4,500 feet and donned our rucksacks. Anderson was blessed with his precious Swiss theodolite which was quite a load in itself.

The track lay through the southern foothills of the Drakens berg Mountains, and on through their fortresses by way of the Mohlezi pass into Basutoland where we expected to be next day. It led us first through Black Wattle plantations, leading later out onto the bare hillside as it climbed towards the pass along the Umkomaas River. On the first day we passed some .derelict farms and found striking examples of how rainstorms can erode unused roads to gullies with potholes 5-6 feet deep in many places. Although this was the track, it is only used by the packhorse trains to-day and these get round such obstacles easily. We were fortunate enough to pass such a trading caravan on our ascent. It consisted of packhorses, mules and long haired donkeys, carrying back supplies of mealie meal, sugar and salt, after bringing out the Basuto wool clip to be marketed at Durban or East London.

The Basuto is a mountain man. Generally his questions are as with most natives, set in a certain order :- Where do you come from ?” ” Where are you going to ?” He is proud of his country, of its constitution and of himself. Although the great irrigation schemes are meeting with success, the re-afforestation of this bare, eroding country is not progressing well, As we ascended we lost the company of the Widowbird. This tiny black bird has an absurd long tail which makes its flight seem almost impossible. Camp was made just after 4 p.m. at 7,700 feet. By 7 p.m. all daylight had gone and the moon shone on what looked remarkably like Harrison Stickle – part of the mountain rampart above us.

In the morning we were delighted by a small herd of the big Eland buck, grazing above our camp. After striking camp, Steinbok were disturbed and fled lightfootedly as we laboured up the steep slopes leading to the Mohlezi pass 9,200 feet high. Before noon we were in Basutoland. In front stretched high undulating tundra-like country, with flat-topped hills sur rounding the horizon. The Mohlezi river flowed as a’small stream in the wide shallow valley guarded by the Redi massif to the east and Thadentsonyana to the west. The Zulu’s version is Taianeng Hlanayane but research after the trip proved the Basuto naming to mean ” Little Black Mountain “; probably due to the cloud that generally surrounds it and it was officially named as such.

Camping that night on the Mohlezi river at 9,800 feet we had a wonderful singsong round the camp fire of both native and European songs, in brilliant moonlight and rapidly cooling air. Fuel here consists mainly of horse droppings which are in plentiful supply. Wild horses were grazing everywhere and herds of cattle were shepherded by Basutos on horseback. Merino sheep and Angora goats were grazing right up to 11,000 feet. One had come to grief on rocks near our camp. The white-necked crows had already pecked out its eyes and the party had begun ; 12 vultures were joining in. These birds take little heed of humans and look unpleasant enough, standing two feet or so off the ground. The natives arrived shortly after noticing the birds from their farm a good few miles up the valley and took the dead sheep back to their kraal where ” high ” meat is considered a delicacy.

On Easter Sunday we were favoured with good weather and the clouds which had prevented us the previous day from surveying the top, did not return. After striking camp we .toiled towards the high grass ridge, the crown of which was Thadentsonyana – the object of the expedition. It certainly was not impressive – merely a flat top to a huge grassy slope. Was it going to be higher than Makheke ? The party was excited and I was in any case extremely happy to enjoy the impressive panorama and mountain scenery. Seventeen miles away to the North lay Makheke ; 14 miles away to the N.E. we could see Giants Castle the popular Drakensberg Mountain. In the east the plains of Natal were visible miles away through the pass up which we had come. To the South Hodgson’s Peak loomed high and behind us to the West lay the Mokhotlong valley. All this country is only vaguely mapped at 1/25,000. Consequently much of it is incorrectly portrayed-and almost unknown. The Basutoland Administration is. at present undertaking a survey of Basutoland, basing its work on recent R.A.F. air mapping of the country. It is interesting to reflect this mountainous British Land lies here, surrounded on all sides by the Union of S.A. Needless to say there is no desire for amalgamation as this is an all-native area. The isolation of the protectorate is no doubt due to its altitude and diffi culties of approach but it must be remembered that we came through the most remote corner of Natal to its counterpart in Basutoland. There are other, easier ways into the country from the Free State.

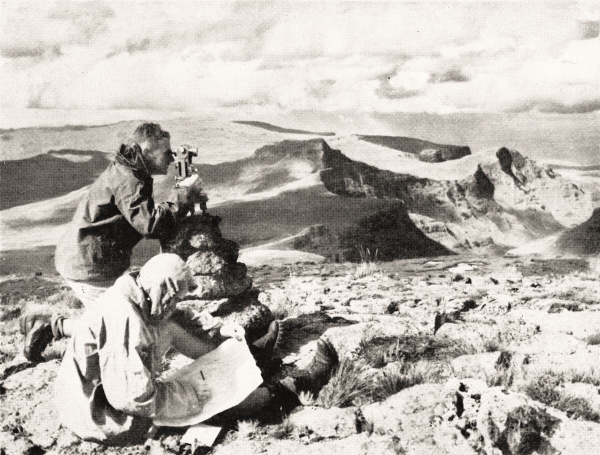

When we reached the top of our mountain, the surveyors got busy shooting angles to known landmarks and engaged in ritual, usual whenever they reached a high point from which they could take a round of angles. As high clouds drifted across the sun, cold struck us and sleet added to our dis comforts. That night we camped just over 11,000 feet on the Senhonghong river. Although an electric storm was going on to the South and far below us, we had brilliant moonlight during the night. At the camp fire, I marvelled at being able to sit on grass at this altitude in the autumn. In Europe would be snow and ice all the year round, while the shelter of a mountain hut would be indispensable. On the tents, next morning, we did find a thick layer of powder frost – presumably dew. It was also interesting to reflect that the river we were camping at was a tributary to the Orange river and would thus end up in the Atlantic Ocean in spite of rising only 100 miles from the Indian Ocean on the East Coast. In all these high rivers, we found masses of tadpoles and frogs.

It was decided to return via the Manguang pass which is trackless like the Umkomaas pass. But whereas the former descends at less than 9,000 feet, the latter starts at about 11,000 feet with a steep rocky scree gully that would not ” run.” Before we began the descent, we cast a last glance back to our peak – now again a mere grassy hump in the north. To the south the extreme end of the swampy Sani plains could be seen a couple of thousand feet below. This is another easier way into Basutoland. Descending through the pass to Natal, rock pigeons, rock-rabbits (dassies) and baboons were our only company. Late that night the main party was back in Durban at sea level and in stifling heat.

Throughout the highlands the vegetation was colourful and varied in spite of it being autumn. In spring, I am told there is a veritable carpet of flowers that follow in the wake of the snows of the winter months. Ski-ing on these slopes would be delightful. Even heather was found at all levels, rich in scent and honey. Much work remains to be done in classifying the flora out here, a rewarding rask for Naturalists and Hill-lovers alike.

The geology in Natal is readily observed due to the tremen dous escarpment and to the kloofs or gorges. Granite is the foundation of this area and runs up to 2,000 feet, followed by beds of Table Mountain Sandstone, Dwyka Tillites (Glacial and estimated to be about 200 million years old). Above these are the Ecca Shales and the Beaufort Beds, composed of sandstone, rich in fossils. At 5,000 feet the Red Beds are found, followed by the Malteno Sandstone. This is the so-called “cave level.” Being soft, the rocks have weathered away leaving the overlying Cave Sandstone as roof. It is in these caves that the well known Bushman Paintings are found. Above these layers there are two distinct layers of Igneous rock. First the Dolorite, estimated at 70 million years and then the Basalt which forms the Cap. These rocks are said to have been created in four great outpours, the last occurring about 60 million years ago. Basalt was then 4,000 feet thick and covered the country to the seaboards. Since then, time and weather has eroded away all but what is left in the Drakensberg, Basutoland and elsewhere with contours over 7,000 feet.

Note.- Thadentsonyana worked out at 11,425 feet above sea level, therefore the highest next to Kenya and Kilimanjaro.