“The Big White Peak”

by G. B. Spenceley

It was someone’s exclamation of astonishment that caused us for a time to give up the struggle for sleep.

We had all been settled in for our first night at Base Camp; the last page in our story of the approach march was written in our diaries, the last candle was blown out, when these superlatives, spoken in a tone of wonder and awe, came to us from the outside world and caused us partially to emerge from our sleeping bags and open the flap. It was worth the effort. Across the glacier, appearing utterly remote and aloof, its base still swathed in cloud, was our 22,000 foot neighbour, Phurbi Chyachu.

We had seen it before only from the distance, still six days’ march away, as we crossed the shoulder of the Mauling Lekh before that dusty descent into the Belephi Khola. Since then we had been too deep in the gorges to see anything but the lower snows of our range. And that afternoon when we had reached the site we might as well have been on some Scottish moor, all heather — or something like it — patches of thawing snow, boulders and cold clammy mist: only the occasional roar of an avalanche warned us of the presence of high mountains, only the features of our Sherpas told us this was Central Asia.

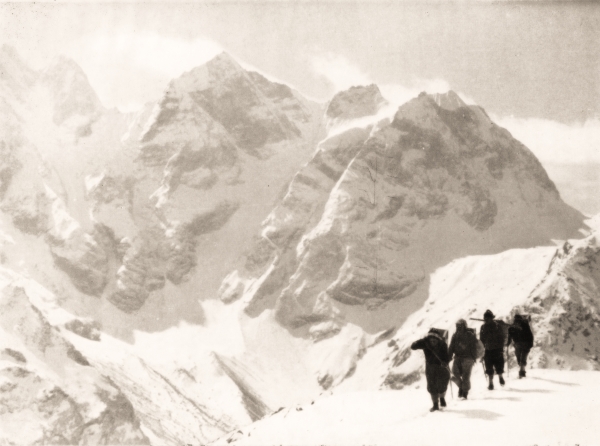

But now the cloud had gone and we could for the first time make out the appearance of this landscape which was to become so familiar. Our camp was pitched on platforms levelled out of a slope which fell with increasing steepness to the snout and moraine of the Phurbi Chyachumba Glacier beyond which we could see to the east a long line of peaks, not high indeed, but bold in feature, terminating at its northern end in one mighty upthrust of snow and ice which was Phurbi Chyachu. Above the camp to the west were a series of rock buttresses and Chamonix-style peaks which formed the ridge overlooking the Dorje Lhakpa Glacier.

The next day, 15th April, was a day of organisation. The Sherpas erected a kitchen — later to be much improved, while Anderson and Tallon, who almost alone understood the complexities of our stores, supervised their orderly packing. Fox and I took time off to search for a suitable Base Line, for survey must be our first duty.

Behind the camp was a steep knoll on which later that day we erected a cairn. This would be one terminal and two miles to the north-east we found another, a sharp pointed little peak rising a couple of hundred feet above the moraine and commanding a view up the glacier to the peaks already fixed by the Indian Survey. At our furthest point where we rested, we saw seven great eagles — later identified as Imperial Eagles, majestically sailing with motionless wings, migrating, so our bird book told us, from the heat of Central India to the plains of Tibet and Mongolia. We returned not over the boulders and rough ground over which we had laboured, but on a yak track, as yet partially concealed below beds of old snow. This was a useful discovery and our Sherpas halted to cairn its way.

It was hardly midday but already clouds were fining up the sky. We were to learn that this was the usual pattern of the weather. All but for one day the morning dawned fine, cold but with a clear sky into which the sun would soon climb to soften the snow. But these brilliant dawns, so full of promise, were something of a snare for usually by 10 a.m. the first wisps of cloud would come creeping over the ridge to the south-west to make us hurry with our task.

Full use of these early hours was vital to our work and this was uppermost in our minds when the next day Anderson and I with our Sherpas, toiled towards the first triangulation point. But though the need for speed was clearly in our minds, it remained there, and this urgency could not be transmitted to our limbs. Neither of us before had been quite so high and our lungs and muscles rebelled at every step. Already the sun was doing its damage and when we turned into a couloir more directly facing the east we plunged to our thighs at every step. A short rock scramble brought us to the crest of the ridge.

We were now on the ridge to the south-west of Base Camp and overlooking the Dorje Lhakpa Glacier. Our thoughts had first been centred on one of the Chamonix-like spires to the north which would have given us rays to both ends of the Base Line. But this was the Himalayas and their ascent could not be undertaken in quite the light-hearted manner we had at first thought. Over the hot valleys to the south already there were clouds and we must be content with a lesser summit nearby.

While the Sherpas built a cairn — a monumental structure erected with great creative zest — Anderson and I surveyed. We looked down on to the Dorje Lhakpa Glacier. At its head, but out of sight from our present viewpoint, was the ” Big White Peak.” This glacier would have given the most direct approach to our mountain, but not only was there no access to it from the Pulmutang Khola, but halfway along its length there was a quite impassable icefall which could only have been turned by a lengthy and hazardous traverse on the left wall, where the climber for a couple of hours would have been exposed to the dangers of an avalanche. Across the glacier we could now see, mounted on ice walls of great steepness, two of the peaks which form the trident of Dorje Lhakpa. We were sure the most bold and optimistic of mountaineers would fail here to find a route, so complete were their defences.

It was on these two points and Phurbi Chyachu behind, that we first sighted our alidade in order to resect our position. While I took a multitude of rays to all visible and noteworthy points, Anderson drew on square paper, supplemented by compass bearings, a panorama which together with the photographs would provide material for filling in the detail. Each point fixed and drawn was christened with a survey name. Such was the routine of each station.

We were not the only surveyors. Fox and Tallon were similarly engaged on the moraine summit that we had earlier spotted; the east terminal of the Base Lane. A good start had been made with the map.

But the brunt of the work that day had fallen on Jones and Wilson whose task it was to reconnoitre a route to a site for Camp I on the Phurbi Chyachumbu Glacier. They had followed our yak track for some way but had been halted by a broad snow couloir. Technically this was no problem, but it was dangerous. Once the security of its banks was left they would be the target for any chance missile. Accordingly they had mounted labouriously upwards until near its head, where the span was much reduced and a reasonably safe crossing could be made. But the entry here was less simple. A steep bank of glacial drift had to be traversed; easy enough when all was frozen, but when softened by sun, an unstable mass of boulders and half frozen mud. A fixed rope was used and it became known as “Dan’s Delight.”

A second couloir proved an easier problem and beyond snow slopes led down to the Phurbi Chyachumbu Glacier. It was here, close to the head of the lower icefall that, the next day, Camp I was pitched. It was a safe site, but objective danger lay all about. Above, but happily not directly above, lay a mass of tottering seracs, while stones and icicles from the soaring walls bounding the glacier, fell to within a few paces of the tents, which themselves were pitched on a crevassed floor in frequent and alarming movement. It was a noisy spot alive with creaks and groans and sudden startling cracks that pierced the silence of the night. It was a place with character and atmosphere but one did not alone wander far from the tents.

While the others were thus engaged establishing Camp I, which was that night to be occupied by Fox and Tallon, Anderson and I again surveyed. The most southerly point of yesterday’s ridge, a rock peak crowned with a square gendarme, had attracted us. It appeared a simple proposition from Base Camp; we could walk directly to it with a short and favourable looking climb at the end. But we were deceived, for just a hundred yards from its base we mounted a slight rise and there at our feet, separating us from the face we had come to climb, was a great cleft, a gorge indeed, cutting deeply into the slope and quite impassable. Perhaps a tortuous traverse might have been made round the head, but this was not for us.

How frustrated we felt ! It seemed for a moment we should have to go north to our previous summit and traverse back along the whole ridge, a most time consuming task, and we did not take kindly to the prospects of again labouring through the deep snow of the gully. Fortunately there was a more welcome alternative. Immediately to our north was the main feature of the ridge, a great rectangular rock buttress with a whole series of minor summits strung along its crest. From afar it would not have tempted us, but close at hand we could see it was not the unbroken granite wall that it elsewhere appeared. There were ledges and terraces, vegetation and patches of easy snow, and from where we now stood, a rake we could see, that would solve easily the first 500 feet of the problem.

We mounted upwards without difficulty, except of course for the difficulty of breathing and moving anyway, but the general angle did get steeper. When our rake gave out in a series of narrowing ledges we turned left and similarly mounted in that direction until further progress was barred by a savage gully. Upwards there was only rock, but good solid rock, split by cracks and chimneys. It was a climber’s paradise but we were not looking for sport. We were explorers and our minds were full of the serious purpose of the ascent. We were racing the cloud which once advanced would make our climb but a useless exercise. We were in no mood to be delayed.

And so we gave our attention to the first line of weakness. Lakpa Noorbu made it quite obvious he wanted to lead. There was no doubt about his enthusiasm, nor later did we doubt his ability, but we felt it hardly fitting, and so urged by myself Anderson started up the first rather confined chimney. It was not easy and for my part I should probably not have got up at all had a jammed ice axe not given me a hold at the crucial moment. The Sherpas were gifted climbers but they had not learned their craft in the best traditions. They had no inhibitions and with a rope above them they saw no reason why they should bother with the rocks. Up the rope they swarmed, hand over hand, while I, without belay, took their weight. Easier but loose rock led to an awkward corner which brought us to the top. We were relieved, for without a common language we found it hard to protect the Sherpas. They took it all in such a light-hearted fashion. They were supremely confident but without regard for danger; more than once confusion reigned, while their actions could be neither directed nor predicted.

Immediately we set up our instruments. It was a good station for at the head of the Dorje Lhakpe Glacier from which we could more firmly resect our position was the “Big White Peak” which yesterday had been hidden behind nearer summits. It was our first close view and we could now confirm that alone of all the great peaks of the Jugal Himal it could be approached with a degree of confidence. We could not yet see the col at the head of the Phurbi Chyachumbu Glacier from which the assault would be launched, nor could we see if from that col we should have to descend, or whether in fact we could traverse across the face without losing height. Of what we could now be certain was, that once established centrally on the face, given good snow conditions, we could climb it directly to the shoulder half-way along the summit ridge. The shoulder was the key to the problem; from it we knew a narrow snow aréte led in the best Alpine style to the summit. If this route failed then there was no alternative. Certainly from the col to the west of the peak there was an easy ascent, but this col, which could be reached only by the longest of routes, was defended by a difficult if not impassable icefall. All other routes if such there are, lie in Tibet.

Cloud once more put an end to our work and we returned, not the way we had come, but along an undulating snow ridge to our tracks of yesterday which we reached up a final slope of deep soft snow which took every ounce of our remaining energy. Soon however we plunged into the gully which we descended in a series of long wet glissades.

Fox and Tallon were having their first night at Camp I where on the 18th of April I should have accompanied Jones on a load ferrying job. But I was laid low with an attack of dysentery, a complaint from which I was periodically to suffer. I excused myself this task and so while Jones shepherded the Sherpas with another consignment of goods I went up the hill to the western Base Terminal where Anderson and Wilson were surveying.

On the following day with our Sherpas, Anderson and I set off for Camp I with the object of estabhshing Camp III on 21st April. On the way up we met Fox and Tallon returning. They had that day carried loads up to the site for Camp II. At this height neither of these men seemed in the slightest affected by altitude. It was not the same with Anderson and myself; although still at a modest height it was for all that a critical one. For my own part I could not eat, I could not sleep, I suffered abominable headaches and every step was an effort of will. I was grossly ill-tempered and not at all impressed by the challenge that had brought us so far. Anderson was little better and would occasionally halt to vomit quietly and uncomplainingly; he was not at all his usual energetic self, a fact for which I was profoundly thankful. Altitude I decided, was a great equaliser. It was in this frame of body and mind that we met these two boisterous and disgustingly healthy spirits romping along the track. They were, it seemed to us, horribly self-satisfied and actually boasted of their speed up and down the glacier. I am afraid that for a moment relations were slightly strained — such is human weakness. But once ensconced in our tents where we had nothing to do but lisdessly he back, while the Sherpas cared for our every need, we felt better and there returned both goodwill and enthusiasm. It was good to be camped on the snow again and feel the tent billow out with the wind.

No direct ascent of the glacier could from here be made, but in the corner where the seracs of the icefall abutted against the containing rock wall, a short rock chmb led to a more level surface. Down it there hung a fixed rope.

The next morning up this rope we hauled ourselves, but it was not the early start we had intended. Before 5 a.m. we had wakened the Sherpas. They are admirable fellows but smooth camp routine is not their best point. It was 7 a.m. when porridge was handed in and we were not away until 8.15 a.m. It was too late; the sun was pleasant indeed, but we did not welcome it on the cliffs above, festooned with threatening icicles. Beyond was an area heavily crevassed through which the best route was already marked. As yet early in the season, it troubled us little and soon we were slogging up slopes interminably tedious.

But to enliven the scene avalanches were constantly falling; small snow avalanches, loosened by the sun; they travelled only a little across the glacier. They caused us hardly to turn round, they were so frequent, but later, when we heard a great roar we halted — we were glad of an excuse. A mass of ice, in size like a small cathedral, broke away from close to the summit of Phurbi Chyachu and fell 6,000 feet down the face, filling the sky with a slowly mounting cloud of snow. We had never before seen an avalanche like it. Awe inspiring and magnificent, it made us realise the might of the forces guarding these inviolate peaks. So far however, except for the icy darts, our route was free from danger and we could stand back and admire these demonstrations of force.

At the site selected for Camp II there was force of another kind, gusts of wind that made the pitching of tents a tiresome task. This was a relatively minor demonstration, nevertheless we were glad to crawl into their shelter. We drank quantities of hot lemonade but for food we had little inclination. Each item of the ration box we carefully considered and each item in turn we rejected. Finally we had a few sardines.

It was a cold night, our sunburn oil became solid ice. Again in spite of an early call the Sherpas were reluctant to be out of tents before the sun brought some warmth to the world. We shared their reluctance but we had a greater sense of urgency. Our route was still straightforward with only an occasional area obviously crevassed. Higher up the glacier where it sharply bent to the west was the Ladies’ Peak whose crest formed the Tibetan frontier. A col on the right might have given us access to that land if we had been permitted to take it. We were to make our third camp somewhere near the lower slopes of the Ladies’ Peak at the foot of which we could see a wide corridor that would take us above much of the final icefall.

Two carries were required that day to supply the camp with sufficient stores. Anderson was suffering his last bout of altitude sickness and when we arrived at a level and safe site we left him there beside the dumped loads, for his presence on the second ferry was not required. He ensconced himself in duvet jacket and sleeping bag and lay warm and snug in the snow dozing until our return. The rest of us made a quick descent and we were able to refresh ourselves with hot drinks at Camp II which was now taken over by Jones and Wilson. With lighter loads and a more direct route back we cut down our time on the return by half an hour. Already the afternoon cloud was building up and with it, wind and flurries of snow. I thought of another occasion, of vital tracks that fast disappeared1, and I suffered a moment’s anxiety. Poor Anderson alone out in the snow, but we found him all right, almost covered in drift and fast asleep. Close by we pitched our third camp.

We were a sorry pair indeed, totally without energy, too listless even to get properly into our sleeping bags. In silent misery, side by side we lay. We enjoyed still each others company, but in conversation we took no pleasure. We could drink, but for food we had little thought — not that, at any rate, contained in our ration box. For my part I had a strange and passionate longing. It was something very simple I wanted, but I could not have it — a poached egg on toast. This longing returned at every camp. It was a blustery cold night and we slept fitfully. I was still troubled with dysentery and sometime after midnight the awful realisation came to me that I should have to go out — this was a regular performance that I had to repeat at most camps. Next day our task completed we returned to Base Camp.

During our absence the rest of the team had been most active. Camp II was well stocked and each day more and more loads had been carried to Camp I. That night with the whole party at Base Camp we celebrated. A luxury box was opened and we sat down to lavish helpings of tinned chicken with rice and curry sauce, blackberries and custard, Christmas cake, coffee and biscuits. We afterwards joined the Sherpas in the smoke of their kitchen and enjoyed till a late hour, a festival of western and eastern song.

The next day was one of rest and reorganisation and we drew up plans for the next nine days. The whole party was to be engaged in a big build-up on the glacier. Camp IV would be established and would be visited by each party in turn for the dual purpose of stocking and acclimatisation. We were to move up in three parties, the composition of which was now changed but each member retained his own personal Sherpa. Our marching orders read something like this:—

| Date | Party | Movement | Camp Occupied |

| 24th April | Jones Tallon |

Base Camp to Camp I | Camp I |

| Fox Spenceley |

Base Camp to Camp I | Base Camp | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Base Camp to Camp I | Base Camp | |

| 25th April | Jones Tallon |

Camp I to Camp II | Camp II |

| Fox Spenceley |

Base Camp to Camp I | Camp I | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Base Camp to Camp I | Base Camp | |

| 26th April | Jones Tallon |

Camp II to Camp III | Camp III |

| Fox Spenceley |

Camp I to Camp II | Camp II | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Base Camp to Camp I | Camp I | |

| 27th April | Jones Tallon |

Camp III, reconnoitre to site for Camp IV | Camp III |

| Fox Spenceley |

Camp II to Camp III | Camp III | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Camp I to Camp II | Camp I | |

| 28th April | Jones Talon Fox Spenceley |

Camp III, establish Camp IV | Camp III Camp IV |

| Anderson Wilson |

Camp I to Camp II | Camp I | |

| 29th April | Jones Talon |

Camp III to Camp I | Camp I |

| Fox Spenceley |

Camp IV, reconnoitre to head of glacier, survey | Camp IV | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Camp I to Camp III breaking camp | Camp III | |

| 30th April | Jones Talon |

Remain at Camp I | Camp I |

| Fox Spenceley |

Camp IV to Camp III remain in support | Camp III | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Camp III to Camp IV | Camp IV | |

| 1st May | Jones Talon |

Camp I to Base Camp | Base Camp |

| Fox Spenceley |

Camp III to Camp I | Camp I | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Camp IV to Camp III | Camp III | |

| 2nd May | Jones Talon |

Remain at Base Camp | Base Camp |

| Fox Spenceley |

Camp I to Base Camp | Base Camp | |

| Anderson Wilson |

Camp III to Base Camp | Base Camp |

The plan of operation was well drawn up. It gave, in the time available, the maximum lift to the greatest height achieved without imposing undue strain; altitude was gradually gained, no march was too long, no climb too abrupt. At the same time the plan provided for each party the opportunity of chmbing high, while for each high camp, there was ensured support immediately below. If all went well we should be in a very strong position at the end of this period. A day or so of rest and we should be ready for the assault.

On the 24th April after the mass carry to Camp I we left Jones and Tallon alone amongst a most impressive dump of stores to which the next day we substantially added. Now it was the turn of Fox and myself to occupy this camp and hasten to the ever creaking icefall. The next day after a night of snow we took loads up to Camp II. The fresh snow on the rock climb delayed us some time, so that we cast glances anxiously up at the rows of lethal darts precariously poised. Wind and limb were by now in better function and we made good speed. Those of us who had before suffered from a multitude of minor disabilities were now for the first time enjoying life. Loads seemed lighter and the pace was no longer the agony it had earher been. Gone too were the listless hours we spent tent bound. Our day’s march was not long, perforce the advancing snow would cut short further effort, and so we enjoyed much leisure, winch was not now wasted in silent self-pity as before. Our diary’s daily entry grew in length and when not thus engaged, or perhaps settling the profound problems of the world, we were engrossed in the great hterary masters.

Exerted by the frequent prompting of Fox, the pace of the Sherpas’ early morning preparations was now funereal and the next day, 27th April, we were out of tents by 6 a.m. We were still under. the shadow of Phurbi Chyachu and it was bitterly cold. The tiresome business of making up loads was sheer misery but once under way, stamping through fresh snow, warmth soon returned. No incident enlivened the tedium of the trudge except that once I broke through into a crevasse, a false step promptly corrected by Mingma Tenzing. He, of all the Sherpas, was the least casual with the rope. The crevasses hereabouts were well concealed and yet bridged but thinly. Later we learned, Jones had fallen some fifteen feet before Ang Temba with a handful of useless coils had checked his descent. Constantly we urged caution to our Sherpas for they refused to distinguish between difficulty and danger. But we suffered no great alarm on this Journey.

Survey was still priority and close to Camp III we left Fox thus engaged, hastily drawing rays before the usual clouds obscured the view. With the two Sherpas I descended for further loads. Half way down we met Anderson with their Sherpas toiling up to Camp III. It was a good effort for they had come up from Camp I heavily laden and were again to return there. We had not anticipated they would that day climb beyond the second camp but the fitness of Anderson, now recovered from his earlier disabilities and the determination of Wilson, who throughout showed remarkable spirit, caused them in their enthusiasm to take on this extra labour.

There were eight of us in camp that night. A day of good work lay behind us and we were a merry party. The camp was well provisioned, Fox had secured a vital survey station and the reconnaissance made by Jones and Tallon was successful. They had not reached the summit of the icefall; distances are deceptive in the Himalayas and after four hours of travelling, cloud had halted their progress. But the route they had taken presented no difficulty and at their furthest point, in an otherwise uncompromising locality, they had found a safe site for Camp IV which we would establish the next day. There was more snow that night and it was colder than we had known it before.

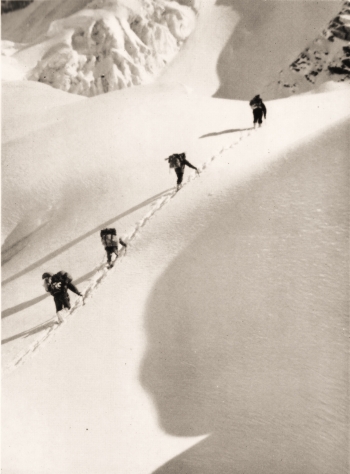

It was cold as well as the altitude that in the morning numbed our senses. It took us an hour with well gloved hands to scrape the tents free of the ice that had formed during the night and to make up the loads for the new camp. “We were away at 7.15 a.m. on two ropes of four, Jones and Tallon with their Sherpas on one rope, Lakpa Noorbu, Mingma Tenzing with Fox and myself on the other. The tracks of yesterday were almost obliterated and for the main in front it was desparately hard work. We took it in turns to lead and stamp a way through the exhausting snow but I think Jones and Tallon took the greatest share of this labour; they were both fit and not unduly affected by the altitude. At 8 a.m. we were out of the shadow of the frontier ridge where we removed sweaters and gloves and briefly basked in the sun. We had gained perhaps a thousand feet of height. The route was straight-forward but not without interest for we were now threading a way through a mass of intricate crevasses and the slope was steeper than any before encountered. It was satisfying to look back at the two tiny specks of Camp III down on the level glacier.

At last we reached the Corridor,” a level and uncrevassed highway skirting the base of the Ladies’ Peak. Anderson and I had spotted this earlier as the best route to avoid the lower barrier of the icefall. Had the slopes above been armed here with ramparts of ice then indeed this would have been the last route of our choice, but there was no such threat. Avalanches of soft snow were certainly falling frequently but before they could reach the level platform on which we walked, their force was spent. Only an exceptional snowfall would make this route dangerous.

Once on “the corridor” we could see the problem ahead. Beyond the point where we would pitch Camp IV the glacier abruptly narrowed and flowed between walls of fantastic steepness — it could be described as the jaws of the glacier. They might not be the jaws only but the fangs too, for here the glacier became steeper and more broken up, the whole area split by crevasses. We knew then that we should be lucky to find between these walls a route free from objective danger. But that was tomorrow’s problem; now we had thought only for the soft snow and our overburdened backs and the release soon to come at the end of “the corridor.”

Another hour or so, punctuated by many halts, brought us this release. “The corridor” which had safely conducted us above the lower difficulties of the icefall had petered out and here the glacier mounted to its height. Close by, where there was little else but seracs and great chasms, was a level bed of snow adequate for our camp. We might have preferred a site a little further removed from the bounding wall but we were on a slight rise and were additionally protected by a series of open and wide crevasses. We had little cause for fear. Wishing us luck, our support party left us alone and hurried down to Camp III. Soon the tents were up and the Primus roaring to give us hot lemonade for which we most longed. Already the weather was deteriorating.

There were still many hours of daylight, but it was too cold to read and write. We burrowed deep into our sleeping bags and talked of tomorrow’s plans. Fox for the first time suffered a headache, a discomfort from which almost for the first time I was free. But of that other plague I still had occasional bouts, and I had a return of it here. At about midnight I realised I should have to go out. For half an hour I pondered over this apalling thought and then slowly and panting for breath I struggled into all available clotiling. Outside it was unbelievably cold; still a wind blew and still we were in mist. When I returned to the tent I put too much weight on the side as I swung my legs over the still sleeping Fox and the rear end of the tent collapsed, carried away from the slim supporting hook from which it was suspended. How I blessed all tent designers ! With a length of nylon line again I went out.

The next morning we were not greeted by the usual sun and clear skies but by wind, snow and mist. There was nothing we could do and all day we lay up in our tents. Although we enjoyed no great degree of comfort, although for reading and writing we had httle inclination and for food even less appetite, this enforced idleness after the efforts of the past days was not altogether unwelcome. We lunched off soup and sardines; these last were frozen in their oil and had first to be thawed out in our sleeping bags. We talked of past days and of future plans.

There was some reason to congratulate ourselves. In the fourteen days since we arrived at Base Camp, no time or effort had been wasted. The survey required only one more station and that we hoped to complete the next day. Four camps had been established, this last at 19,000 ft. and we had a considerable buildup of stores at a high level. Tomorrow we should solve the problem of the final icefall and after two days rest at Base Camp, would begin the attack. Acclimatisation was progressing satisfactorily, we were a fit, united and happy party; with three weeks in hand we had every reason to be optimistic of success.

Of these things we talked and not for the first time I admired Fox’s leadership. He was kindly and considerate yet also a driver, or would have been, if there had been need. But if he had been prepared to drive, he drove himself harder and he took upon his own shoulders the tasks least pleasant and most demanding. He showed a single minded devotion to the enterprise and he was utterly determined to justify the confidence placed in the party by the Club and those who had given their support. He said that day “If I can get two men to the summit of our peak it will be the happiest day of my life.” As leader of a Himalayan expedition, the climax of a fine mountaineering career, he was completely fulfilling himself. As leader, mountaineer and as a man I admired him, as did we all; certainly there was no one whose company I should have preferred, tent-bound during a long day of wind and snow, than that of Crosby Fox, the dear friend and companion of many mountain days. Little did I then imagine that it would be the last we should share together.

April 30th dawned clear, gone were the troubled skies and the wind. We were out of tents just as soon as it was light. It did not take us long to gather the survey equipment; on this recon-naisance we needed to take little else. From the tents we moved round a serac more centrally into the glacier. We could see the jaws, but standing below them, all was too foreshortened to see the problem. We could not plan our route, we could but progress upwards hopefully, taking the route least tortuous, avoiding the bounding walls. We were still in shadow and it was extremely cold.

For several hundred feet we mounted keeping safely in the centre of the glacier. There were crevasses in plenty but so far they were bridged in some part of their length, although but thinly. We dare not romp across them and our pace was slow and cautious.

We were slow too for another reason; we were higher than we had been before, there was soft snow and Fox was for the first time troubled by altitude. It was this last that caused me to take over the lead somewhere through the icefall, a position I was to keep for the remainder of the day. Fox now came second, to give me security over the fragile bridges. That change in the order of the rope was the first link in the chain of circumstances responsible for my survival. For a little way more we climbed, moving in a zig-zag pattern, but safely in the centre of the glacier. But this was too good to last; suddenly we came to a series of large crevasses, unbridged and unbridgeable, spanning the greater width of the glacier.

There was one way round them, easy and short on the true left bank of the glacier. But here where we proposed to turn them, we were for perhaps ten minutes in the ascent exposed to the possibility of an ice avalanche from a series of ice cliffs high above. A snow avalanche we knew might well fall, indeed they were falling every day everywhere, but from that danger we had little to fear, it was like “the Corridor,” never were we sufficiently near to the bounding wall for it to be a serious menance; only the ice cliffs threatened. I say threatened, but in fact they looked uncommonly secure, there were no tottering seracs, no avalanche scars, at their foot no sign of debris. Yet had there been any other route we should have taken it; there was none, except one even more perilous on the other side. We were aware of the danger and gave it full consideration, but there was never any real hesitation or doubt, this was a justifiable risk. Already we had learnt that in the Himalayas some risks must be taken, not the risks which every mountaineer must take wherever he may climb, risks over which his skill and experience have almost complete mastery, but objective risks, dangers against which skill and experience offer no protection. One can only pray for luck.

We turned the crevasses and in ten minutes we were once more central in the glacier. We did it quite casually, time was not wasted nor did we desperately hurry; the odd glance we may have cast up at the seat of danger but we suffered no strain or great anxiety of mind. The odds were too heavily in our favour. Soon we were close to the summit of the icefall, only a few crevasses remained. What faced us now was a weary plod which was to continue for four hours. We rested often and at one of these we saw four tiny figures far below on “the Corridor.” It was Anderson and Wilson with their Sherpas corning up with further provisions to Camp IV. The big build-up was continuing, our position for the final assault becoming stronger. Already twenty-eight loads were at Camp III or above.

Distance had again deceived us. It always appeared that a few yards more and the angle would level out; it never did. Our pace was slow; we were all conscious of the altitude and the soft snow did not help. Fox remarked that never before had he suffered such a hard mountain day. We seemed to be immensely high; Phurbi Chyachu which soared so majestically above the Base Camp appeared from here quite insignificant. Over the col to the north of it we could now look, and beyond it in Tibet, were noble unknown peaks. In front, obscured partly by its eastern ridge was the “Big White Peak.” There was nothing in its appearance to suggest defeat and no longer did it fill us with awe as when first we saw it, as an aloof, utterly remote triangle of snow.

Still we plodded on but at last the angle did relent. Even so we were too far from the col overlooking the Dorje Lhakpa Glacier to reach it that day, for already wisps of cloud were hovering round the tops. If we were to survey, then we must do so while we could. It was 11 a.m. and for half an hour we worked in this cwm of great peaks until deteriorating weather put an end to our task. We lingered there no longer, the wind was rising and we were glad of an excuse to leave.

We were in good spirits; we had accomphshed almost all that we had hoped to do. The way, the only way through the icefall had been found, the last essential survey station had been taken, it had been desperately hard work, but we had not collapsed and now on our downward track the past exhaustion was forgotten. We had thought only for long drinks of hot lemonade and the relaxation and the pleasure of each others company which soon we should enjoy in the tents below. I doubt if either Fox and I ever in our mountain experience, felt more contented in mind than on that fatal descent. Great too was the relief to be walking downhill and we made a merry speed in keeping with our spirits, as fast almost as on lower mountains and we found now no need for rests.

But if we did not rest we did once pause and this sealed our fate. We had been in cloud almost from the summit of the glacier guided only by our upward tracks. A few crevasses warned us when we reached the head of the icefall but we had not now the visibility to know exactly our position. When we heard an avalanche for half a minute we stood and listened. We were not alarmed; it was close but not dangerously so. It was the usual small snow avalanche of the kind that every day we heard and saw; behind it there was no great force. This had not the roar of the great ice avalanche that we had seen come down the face of Phubi Chyachu, there was no boom to it, just a gentle swish of slowly sliding snow. When silence had returned we continued in our tracks.

A minute later we recognised our position. The crevasse on our right was the one by which to turn, we had that morning hazarded the icecliffs. Now on the descent, our moments of peril, if so they could be described, would be even briefer. We certainly gave them little thought. Soon we were at the furthest point, the point nearest to the cliffs. We turned the crevasse and were now walking back towards the centre of the glacier and safety, walking between two great crevasses. Thirty seconds more and we should be free from danger, but our thoughts were of other things and nothing ominous clouded them.

Then, just as the last man on the rope had turned the crevasse we heard it; a mighty roar from high above. There was no mistaking what it was or where it was corning. It was a great ice avalanche. We ran as fast as we could, every second the thunder swelling, but we could only make a few paces before it was on us. We knelt down, crouched, pathetically braced for the impact, as if with our muscles we could beat off its force. In the last second I looked round, on the upward slope was the gaping crevasse which gave a feeble hope, behind a great cloud of snow advancing and outlined against it, bent and braced as myself, three figures, Crosby Fox, Mingma Tenzing and Lakpa Noorbu. That was the last I ever saw of them.

I was in motion pushed by an irresistable force, then almost immediately I felt myself falling. I knew I was going into a crevasse, but my fall was not far. A great force of snow followed me which desperately with my arms I tried to ward off. Buried, or pardy buried I must have been for all was dark yet still with my arms I could fight.

How long I lay there I cannot say, but abruptly vision returned. All was strangely still and quiet. I was 25 feet down at the extreme end of the crevasse. Where I lay it was narrow, my body almost spanned the walls. Although still alive and apparently uninjured my position would have given me little comfort, but I could now see that in the centre of the crevasse where it was widest, the avalanche debris had formed a cone, mounting up to within a few feet of the lip of the crevasse. At least I knew I could get out.

I was still suffering from shock and it was some time before the full horror of the situation entered my dazed mind. I could not yet believe that Fox and the Sherpas were not just outside, unharmed as was I; the awful alternative I refused to grasp. When I had struggled free from the snow I tried to shout to them, but no sound could I make. I was gasping for breath as I had never done before and for some minutes I had to lean against the wall before I could make a second attempt. But my voice was lost, absorbed by the ice around me. I had strength now to move and I made a few steps up the slope towards the centre of the crevasse to be halted shortly by the rope. Before I had not thought to look for it; the rope that tied me to my companions 20 feet part. It was not broken. I followed it back to the little pit from which I had emerged. It descended vertically into the floor. Only a few feet could I pull free; no portent could be more ominous. I had now no axe and I could dig only with my hands. At first the snow was soft and a little of the rope I cleared, but soon I came to hard compacted snow and ice in which I could make no impression. I knew then there was no hope, below that solid floor no man could live.

I untied from the rope and climbed out. For some time I walked around trying to orientate myself. I peered into another crevasse, likewise filled with debris, one of the dark pits round which we had walked that morning, but I could see that no victims could be there. The crevasse into which I had fallen was immediately below the position the whole party must have occupied at the time the avalanche struck. All must have the same grave, yet with a fragment of hope I looked around and called out once more. It was an awful deathlike silence into which my voice feebly penetrated. Nothing relieved the whiteness around me. I felt very much alone.

I need not describe my descent nor the thoughts with which I was accompanied. Soon, a little below, I picked out our morning’s tracks which I hastily followed, now crawling over the more dangerous of the snow bridges. I stopped at the pathetically empty tents of Camp IV and found from Anderson and Wilson a message. They were having trouble with the Primus stove at the lower camp and had decided to return that day to Camp I. This was a blow indeed. I packed a rucksack with a sleeping bag and a duvet jacket; I felt strong enough then but some sort of reaction might follow before I could go so far. Again I set out.

Fortunately there was no difficulty and little danger. I was in a sorry state of mind but as I came down the last slopes leading to Camp III, imagine my joy to see, standing beside the tents, a figure in red windproofs; Anderson. The camp after all was occupied. Soon kindly hands were looking after me while I told my tragic tale.

Only I had seen the crevasse, I only knew there was no hope. With the others some slender hope still existed. Wilson with Pamba Tenzing immediately set off for Camp I to carry the news; a fine effort for they had already suffered a most exhausting day. We left behind could only wait for the morning. I was glad of the quiet comfort of Anderson’s company until later sleeping pills relieved me of that agony of mind from which; I suffered.

Prompt action was immediate upon Wilson’s arrival at Camp I. Jones and Ang Temba set off in falling light for Base Camp to collect the spades. After snatching a brief spell of sleep they, departed at 3 a.m. returning to Camp I from where Tallon and Pemba Gyalgen now took over and in the first light raced up the glacier, followed a little behind by the former pair. Wilson and Pemba Tenzing came up later with an additional tent and sleeping bags. With them there burned a feeble flicker of hope expressed by both Sherpas and Sahibs in this prolonged and hectic endeavour.

Anderson and I did not share this spur but we also were away early and were soon making our way along “the Corridor.” It was from this height that we first saw the others far below on the glacier, two pairs, as yet mere specks, but moving fast. Indeed we did not have long to wait at Camp IV before we were joined by Tallon and Pemba Gyalgen, and Jones and Ang Temba were not far behind. Their climb that day was a remarkable performance of speed and endurance which deserves the greatest credit. Only I knew it was to no purpose.

The sun was now fully on the ice cliffs, under which we should have to work. The possibility of a second avalanche was remote but nevertheless it seemed needless to risk further the lives of our Sherpas and accordingly only Anderson, Tallon and myself climbed up to the crevasse. Lhakpa and Pemba set to work to prepare a well deserved drink with which to welcome the arrival of Jones and Ang Temba.

When my companions saw the end of the rope from which I had untied and the solid floor of the crevasse in which it was embedded any hope they may have still nursed was soon shattered. We calculated that the two Sherpas must be buried under not less than 50 feet of debris, somewhere in the centre of the crevasse. In the narrow end, perhaps wedged between its walls, was Fox, buried under not more than 10 feet of ice and possibly much less. It was there that we set to work, one at a time, crouched in that confined space, digging into die ice. We changed places every few minutes, for we were soon gasping for breath, while one sat outside to give warning of an avalanche. For over an hour we worked, but so solid and hard was the floor that after that time we had gained little more than a foot. At least we could confirm yesterday’s judgement; death must have been instantaneous.

It was now midday and I felt we should no longer expose ourselves to further danger in this fruitless labour. We would come again tomorrow before the sun was high, but for the moment we would abandon the scene and join the anxious party waiting below at the camp. Indeed it was a melancholy group that sat disconsolately round the tents. They did not need to see our faces or hear our report to know that the miracle for which they had hoped and which had spurred them to such resolute effort, was not to be; our early return was evidence enough.

Perhaps the full force of the tragedy had not made its impact upon the Sherpas until that moment. Our return and the sight of the empty tents brought it forcibly home. It was natural that it should be as great a blow for them as it was for us. They came all from the same village; all had lost friends, some relatives. They are simple child-like people whose faces portray their emotions and now they were as quick to tears as before they had been to laughter. But it was not only for their own race they wept, Fox was loved as leader and man not only by ourselves, and his loss took some share of their grief. Lhakpa Tsering, the least sophisticated and the most lovable of our men, emerged weeping from the tent holding in his hands, plaintively, Fox’s few personal possessions, his face reflecting the desolation that filled all our hearts. In these solemn moments of mutual anguish the gulf between us of race, religion, language and culture was firmly spanned and we felt a close affinity with our Sherpa friends.

While soft snow avalanches fell leisurely down the slopes of the Ladies’ Peak, which we now watched with a fresh apprehension, we sat outside in the sun and discussed the mournful facts, while gaining some little comfort from each other’s company. No hope was there now in anyone’s heart and only a little hope was there of recovery of one of the bodies; yet to do this we would make one further effort and certainly the Sherpas must see for themselves the scene of the tragedy. This was to be done the next day, early too, before the sun could unleash further destruction. Jones and Tallon with their Sherpas stayed at Camp IV while Anderson and I returned to the lower camp where Wilson was waiting anxiously for news. Signals for next morning were arranged so that if necessary we could be called back. I reproached myself afterwards for this decision for it was really my place now to share also this second search, but I confess I shunned a further night in that tent of tragic association, still littered with Crosby’s possessions. If it was a breach of duty I was forgiven, but it was no pleasant night for the others either.

Again I was grateful for Anderson’s company. This time drugs left us unaffected; neither they or physical weariness could still our thoughts and we pondered long on future plans. For the moment we hated these mountains and there was little heart for further work. Certainly we could no longer attempt to climb the “Big White Peak”; not only were we now too weak as a party but never could we ask our Sherpas to carry loads up the glacier round the crevasse in which their friends were buried. We could not ask this even though the risk was reasonable. But if we could not climb there was no limit to the other work we could do. The map we had so carefully made was lost, this we must do again, and more; on both sides of this central glacier we could extend it to the very fringes of the Jugal Himal, even to the Langtang. A good map would be no mean memorial to Crosby Fox and while there were no peaks here we could climb, perhaps on some glacier to the east or west, a lesser mountain we might find whose ascent would reduce our failure. Only in work could be escape from our gloom. Discussing these plans some enthusiasm returned but this was not work in which I could for some time share. My own duty was clear; I must immediately and with the greatest haste return to Katmandu to report the accident.

To fulfil these plans no time could be lost. Certainly we should all be glad to leave the glacier, but before we could all retreat there was work to do, there were three vital survey stations to be retaken. Regrettably the remaining instruments were at Base Camp and there would have been a sad delay had not Anderson volunteered to get them. Accordingly early the next morning, while Wilson and I waited for the signals we did not really expect, Anderson and Lhakpa Tserring left on what was to be a further achievement of endurance. In eleven hours of continual marching they descended to Base Camp and returned to Camp III, this without the spur that had driven the others; they had just a sense of duty and superb physical fitness.

Wilson and I waited a few restless hours watching for the signals. This enforced idleness was no help to our spirits, but only added to our gloom. It was some relief to see at 11 a.m. four burdened figures on “the Corridor.” Camp IV was being abandoned. They had taken the Sherpas up that morning to the crevasse, a little further they had dug but all could see that their efforts in that hard ice and confined space were fruitless. The Sherpas were satisfied that nothing more could be done and were not anxious to remain longer. The ice will be their tomb, where forever they will be preserved and perhaps it is appropriate that this should be so.

In spite of the strain of the last two days and the fatigue obvious on their faces, Tallon and Wilson offered to remain two more days on the glacier to remake the map. And so I left them with their Sherpas, and Jones, Ang Temba and I made our way down to Base Camp where much work awaited me before I could depart for Katmandu. Even this journey, so often trodden, was not without its excitements for soon I was swinging breathless ten feet down between ice walls. I was grateful for Jones’ prompt action with the rope. A little below Camp II we met Anderson and Lhakpa Tsering returning and I was glad of the ice axe they had brought me, so that in the final icefall there were no more abrupt descents. We reached Base Camp in heavy snow,

The following evening Anderson returned soon to be glued for a whole day to the typewriter and on the evening of 4th May the whole expedition was safely at Base Camp. Successfully Tallon and Wilson had plotted the upper reaches of the glacier. The party with an interesting programme of exploration and survey was left in charge of Anderson and the next day with Murari and Passang Chittong I left for Katmandu on the saddest of all missions.