The Northern Alps Of Japan

by R. Gowing

The islands of japan occupy an area of 142,338 square miles, of which probably eighty per cent, could be classed as mountain or hill country. Of this a great part consists of either tree-clad hills or active and dormant volcanoes, offering a wide variety of scenery to the hill walker and motorist, but little to the climber.

Most of the peaks of interest to the mountaineer belong to the several groups of Japanese Alps, so named by Weston, in the prefectures of Saitama, Yamanashi, Shizuoka, Nagano and Toyama in Central Honshu. They are largely of granite, though they include some volcanoes, both extinct and active. Outside this area there are a few isolated peaks of interest to the climber and, as in any country, there are outcrops to’ be found in many places. None of the mountains is above the level of permanent snow, but during the winter the possibilities for snow and ice climbing and for ski-ing are quite extensive.

Though mountains have long been climbed in Japan for religious reasons, mountaineering as a sport dates mainly from the explorations of the Rev. Walter Weston, an English missionary who was active at the turn of the century. He helped to found the Japanese Alpine Club, which recently celebrated its 60th anniversary, and wrote two classic English-language books on mountaineering in Japan: Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps (1896) and The Playground of the Far East, besides other books of a more general nature on Japan. Information in English on the Japanese mountains is scarce, apart from journal articles; the Rev. W. H. Murray Walton’s Scrambles in Japan and Formosa probably completes the published bibliography. The Japanese mountaineer is well provided with a comprehensive range of guide-books and maps. The latter, once one has had the Kanji place-names transliterated, are very helpful, with all walking routes marked with the time required.

Since Weston’s time, mountaineering has grown into a popular sport. Every university and district has its alpine club and hiking clubs are as numerous as in Britain. Japanese climbers have won international repute dating from Maki’s pioneering of the Mittellegi ridge of the Eiger in 1921 to more recent exploits in the Andes and Himalaya, including the successful campaign on 26,668 ft. Manaslu and many other difficult peaks (see, for example, Alpine Journal, LXX, page 213). Japanese equipment is excellent, often betraying a welcome reconsideration of the principles behind its design; it is reasonably priced and with a few imported items, such as the ubiquitous Bleuet stoves and cylinders, is available in sports shops in most towns. Our local sports shop is run by Yoshino Hattori, one of the leading young Japanese climbers, with considerable experience of difficult routes in the Japanese and European Alps.

The mountains are readily accessible, though the unmade nature of most of the non-trunk road makes reaching them take longer than the map would indicate. Many of the more touristy hills have fine “sky-line” toll-roads, funiculars and cable-cars. All the hills and mountains are well provided with paths, very necessary in the prevailing vegetation, and huts where one can live Japanese quite cheaply.

Tokai, where I was working on the commissioning of the British nuclear power station, is on the Pacific coast, near the northern edge of the central, or Kanto, plain. Northern Ibaraki has some pretty hills, 2,870 ft. Tsukuba-san offers good views of Kanto and the surrounding hills, but the nearest mountains are a good half day’s drive away.

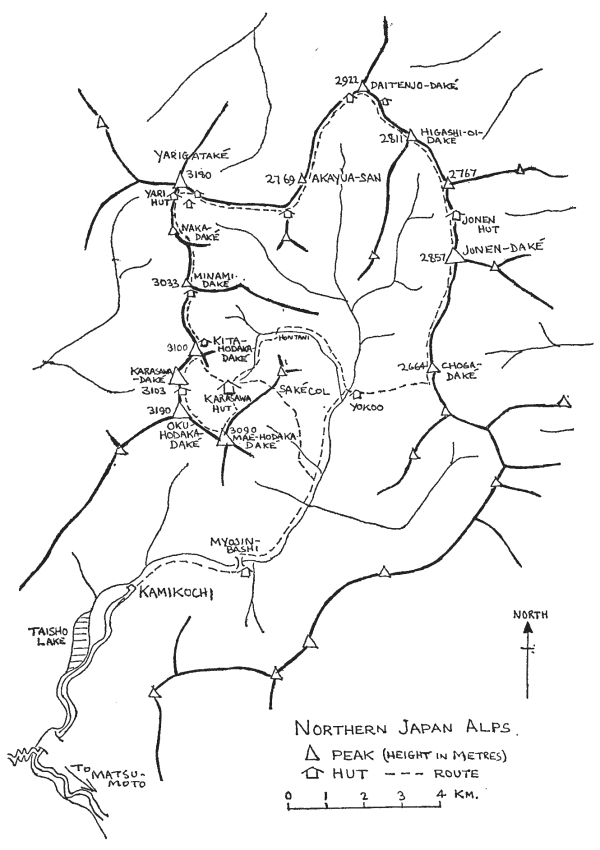

Early one Saturday in September, 1965, 1 set off with three colleagues, Tom Gerrard of the Rucksack Club, Kevin Viehoff and Joe Day, for a week’s walking, climbing and exploring in the Northern Alps. Since in the notes which follow about our activities during that week I have unavoidably used local Japanese names, the brief glossary which follows will help to interpret their meaning.

| San, yama | : mountain. |

| Ken | : prefecture or county. |

| Kanji | : Chinese-Japanese characters. |

| Mura | : village. |

| Ryokan | : Japanese style hotel. |

| Tatami | : thick straw matting which completely covers the floor of Japanese living rooms. |

| Futon | : bedding—both mattresses (rather thin, laid directly on the tatami) and quilted covering. |

| Dake | : peak. |

| Bashi | : bridge. |

| Cryptomeria | : Japanese cedar tree. |

| Sanso | : mountain hut. |

| Minami | : south. |

| Kita | : north. |

The drive to Matsumoto, at the foot of the Northern Alps, occupied the whole of Saturday. A mixture of surfaced and unsurfaced roads took us to Takasaki, on the edge of the hills, where we lunched on prawns, rice and coca-cola in a small restaurant on the main street. A good road led us in heavy traffic over the 3,300 ft. Usui-toge pass to Karuizawa, a popular tourist resort at the foot of the active volcano Asama-yama, and down to the town of Ueda. From Ueda we followed a rough but scenic road over another 3,300 ft. pass to Matsumoto, which we reached towards 5 p.m. After briefly exploring the city, which has a fine castle, one of the few original remaining in Japan, we enlisted the help of the information office at the station to book us into a ryokan, or hotel, in a spa a few miles out.

First day. We set off at 7 a.m. on a Sunday morning of low mist and drove down into Matsumoto where we picked up three of our Japanese colleagues, Ohtake, Nakano and Tanaka, before setting off for a very scenic and quite exciting drive up to Kamikochi. The road is very rough, the crux being a single track tunnel that requires bottom gear, from which we emerged to a grand first sight of Hodaka, a high, jagged ridge mirrored in the Taisho Lake. Shortly afterwards we reached Kamikochi, hot spring resort and, at nearly 5,000 ft., principal centre for the Northern Alps, where we left the cars.

Here we loaded up with climbing and camping gear and a week’s food, then we set off along a broad track through the woods to Myojinbashi, where we stopped for a drink at the inn. We crossed the suspension bridge and followed a path through tall cryptomerias and waist-high bamboo grass. The path was good, and pleasantly shaded; here and there it diverted around fallen trees, or crossed a stream by a plank bridge. At Yokoo we crossed a tributary which flows down from the Hodaka group, and took a path ascending above its left bank. Above, on our left, rose the steep rock wall of Yokoo Dani; past this the path crosses the stream by a small wire suspension bridge at Hontani. We now split up to allow the fit men to go ahead and pitch camp, while Viehoff and I pottered up in the pleasant company of two girls. After a steep ascent up a moraine we reached the Karasawa Hut in failing light to be greeted by our colleagues, Hiraoka and Kuzushima, who guided us to our camp. This was a pleasant spot at 8,500 ft. in a broad, flat-bottomed corrie surrounded by the peaks of Hodaka. The cool mountain air was a delight after the heat of Ibaraki; after a light meal we turned in for a comfortable night.

Second day. It rained in the latter part of the night. Early in the morning we were woken by the occupants of neighbouring tents doing their morning exercises “ichi, ni, san, shi . . .” prior to setting off. We breakfasted and waited awhile to see what the weather would do, then retired to our tents. Our neighbours of the Aoyama University Alpine Club soon returned, and soon after we too gave it up and beat it to the hut.

The Karasawa Sanso is a fine example of a Japanese mountain hut, being closest in pattern to the Club Alpin Francais style, modified to accord with Japanese custom. The big living room has a picture-window and a central oil stove; the kitchen and the tatami version of the usual ‘matrazenlager’ open off it. There is room for self cooking or one can have the meals provided by the hut staff; our Japanese colleagues did not recommend these, so we chose the self cooking method. We spent the day in great warmth and comfort, with occasional sorties to divert water from the tents and to collect food. We bought rice and ate our tinned salmon and bully with it, we drank numerous cups of green tea as we sat around with our Japanese friends. Towards evening we cooked dinner, then those of us who were not flooded out retired to the tents; by this time it had stopped raining and we even saw a few stars.

Third day. The day started overcast but not unpromising with the odd patch of blue sky. We set off at 7.30 a.m. up the cwm over boulder fields, then steeply up to the south east on scree and on a path bordering a scree/neve gully leading to Go-Roku Koru (5-6 Col) on the NNE ridge of Mae-Hodaki, which we reached in an hour from the hut in clearing mist. We climbed the ridge, covered in shrub pine, to Point 5. From here pleasant scrambling on good granite led us to Point 4 in half an hour from the col. Hiraoka, who knows these mountains, took charge at this point and led us up by steep but quite easy scrambling reminiscent of the Cuillin, to Point 3, over Point 2 and, in two hours from the col, to the 10,140 ft. summit of Mae-, or front, Hodaka-dake.

We were now in mist which continued the rest of the day, damp and at times drizzly, to remind me even more of our day in 1961 on the Cuillin Ridge. We continued along the Tsurione or Hanging Ridge; Gerrard and I followed the crest for a while, which was quite interesting but soon we decided to accompany the rest of the party on the track which, like that on Striding Edge, mostly contours just below the crest. In this way we reached at midday the 10,450 ft. summit of Oku, or back Hodaka-dake, the highest point in the Northern Alps and the third highest in Japan, with a panorama indicator and a small shrine. From here twenty minutes of descent, on a good track well marked with paint splashes, led us to the Hodaka-dake Sanso on the col.

Resisting the temptation to pass the time of day with the pretty occupants of the hut we pressed on. Forty minutes from Oku-Hodaka we reached the multi-cairned top of Karasawa-dake, then chains led us down a gully as we followed a descent somewhat like that of the Hornli. We walked and scrambled on in the mist and caught up the leaders just below the Minami-mine (south peak) of Kita-Hodaka. Some of the party then went down while the rest of us visited the main top (10,160 ft.) of Kita-Hodaka, the actual summit of which, like Sgurr Dearg, is a little pinnacle just to one side. We descended the south east ridge of Mina-mine, a path following the ridge at first, then a rocky rake towards the main south east gully of the mountain, down which it zigzagged through the vegetation.

We came out of the mist a few hundred feet above our camp, which we reached at 3.15; I do not think I was the only one feeling very tired. We went to the hut and had a good meal of Ramen, Japanese noodles produced from packets by Hiraoka, then he and the other Japanese members of our party set off down. We spent a happy evening standing beer to the hut warden and his associates, having just enough Japanese and English respectively to converse simply.

Fourth day. Wednesday dawned fine; we left the hut towards 7 a.m. to retrace our steps to Kita-Hodaka. As we climbed among the flowers and scrub pines the views opened out, of the Hodaka range, of smoking Asama and, far beyond, of the unmistakable shape of Fuji-san. We reached the top of Kita-Hodaka in two hours, to be greeted by the sight of Yari-gatake, the Spear Peak, some miles to the north. Away at 9.15 we followed a path descending steeply to the NNW, bounding the steep but loose looking Takidani walls. I stopped to photograph the blue-flecked yellow gentian which grows profusely on all these mountains. After descending thus to about 9,200 ft. we followed a pleasant rocky crest, with the route well marked by chains, yellow paint and nail-scratches, meeting several parties, to Okirido Col at about 9,000 ft.

From Okirido we had an interesting scramble up the rocks of Minamidake, 9,951 ft., the final crags being turned by an easy path to the left. We reached the rock peak soon after 11 a.m. and spent half an hour enjoying the fine views before continuing past a hut to the rounded summit. A fairly steep descent to a col was followed by a zigzag ascent, decorated by small blue gentians, to the 10,105 ft. summit of Naka-dake. Throughout the trip I was impressed by the beauty and variety of the alpine flowers at this late season and very much regretted that my Reflex was at the makers for repair. From Naka-dake it was fairly level to the main Yari Hut which we reached at 1.30 p.m.

After a brief rest we left our sacks for the grand climax to our day and to our trip, the ascent of the mighty Spear Peak. Avoiding the paint marks, chains and other aids with some difficulty we made our way up the steep rather shattered rocks. Some ten minutes later we were on the 10,433 ft. summit of Yarigatake. The fairly roomy top was shared by an indicator, a small shrine, a symbolic spear and a considerable amount of litter. Seated upon the indicator to rise above the stink of the litter I enjoyed the extensive view, of mountains, of steep sided valleys and of Fuji-san 92 miles away. We strolled down and lazily examined Koi-Yari, the impressive pinnacle on the north west side of Yari, rejecting our only chance to use the ropes which we carried throughout our tour. We booked in at the hut, pottered around outside enjoying the views, dined on dried potato and bully and soon after the beautiful sunset retired to a fairly comfortable night among the futons.

Fifth day. On Thursday we rose as usual soon after first light. The clouds were high but ominous and a strong wind was blowing. We set off about seven and followed a path across the south east face of Yari, past the upper hut on the east ridge. The path wound through vegetation on one side or other of the ridge as we descended to the Mizumata Joetsu col, an hour from Yari Hut. Soon afterwards the rain started: we put on waterproofs and continued climbing fairly steeply to the Nishi-dake hut, in whose porch we stopped for a bite and. an extra sweater. We went on in the rain over 9,085 ft. Akayua-san, on a path of granite sand which gave good going. It was quite windy and cold and the sections of path in the lee of the ridge provided welcome respite. Numerous flowers, the blue-flecked yellow and the purple gentian and a pretty eye-bright amongst others, and a family of ptarmigan, diverted our minds from the rain. Three hours out from the Yari Hut we stopped for a break outside the Daitenjo Hut, on the col below Daitenjo-dake.

Viehoff and Day followed a path turning Daitenjo-dake to the right while Gerrard and I took the alternative path contouring it to the north and struck up its north west ridge of loose granite. Fifty minutes from the col we reached the 9,587 ft. top of Daitenjo-dake, crowned by a shrine with a little stone image in it.

The path continued easily along a pleasant ridge with various flowers, including the frondy-leaved, peculiarly shaped pink, ‘dicentra pusilla’; we also observed ptarmigan, iwari-bari (rock-bird) and other small birds. I think the ornithologist as well as the botanist could have a good time in these hills. We crossed the 9,222 ft. Higashi-Oi-dake soon after midday and went on over Point 9,078 ft. to descend steeply through pine woods, reaching the Jonen Sanso at 1.10 p.m. This was our objective for the day and we were not sorry to get there.

The warden and his son welcomed us with the customary green tea and we changed into what dry clothing we had, hanging our wet things round the wood stove; fuel is no problem in huts in these tree-clad hills. We spent a pleasant afternoon sitting round the stove, watching T.V. and drinking our hospitable warden’s coffee and best Suntory whisky. Later on a few more people came in out of the rain including a teaching dentist from Osaka Dental School who spoke quite good English.

Sixth day. Next morning we rose to find mist clinging to our col and everything looking very damp, and we left in rain which steadily worsened as the day wore on. The warden saw us off at 8 a.m. for a hard plod up 9,373 ft. Jonen-dake, whose shrined top we made in under an hour from the hut. We followed the ridge which wandered about the 8,500 ft. level, much of it through trees and vegetation which would have been pretty on a better day. Eventually the path climbed out of the trees to 8,740 ft. Choga-dake (Butterfly Peak) over whose wind-swept top we continued 300 yards south to a slight col where we spotted the track going down westwards. It soon brought us into the forest and at 11.45 we reached the main valley beside the Yokoo Hut.

From here we followed the familiar path to Karasawa in rain and wind of increasing severity, which was blowing the waterfalls horizontally from the crags of Yokoo Dani towering above us. We went straight to the camp site which we reached in a fury of rain and wind, to find our tents flattened and Tom’s damaged. We bundled them together and carried all the remaining gear to the hut where we hung up the tents to dry and started on the job of drying ourselves and clothing. My sack had not resisted the rain but fortunately I had left enough dry clothes at the hut. The rain had eased off when we turned in for a comfortable night on foam-rubber filled futons.

Seventh day. To some scepticism Tom announced that it was clear but a glance out of the window showed that it was indeed so. We breakfasted, packed up and, with fond farewells and presents of matches and towels, started on a rising traverse, following a rather precarious path through the trees to reach Sake col in threequarters of an hour. We lingered to enjoy the fine views of the Hodaka peaks and of Yari on the one side and of the Kamikochi valley on the other side of the col; I waited for Oku-Hodaka to clear so that I could photograph it.

Then I set off down the cwm to the south east; the path giving good swinging going at first but later becoming very difficult with roots and boulders. I contoured into the lower reaches of the next cwm, where I had to follow the stream bed for a while before picking up the track again and got to the valley in just under three hours from Karasawa.

The track led on through the cryptomeria forest, past the suspension bridge Nimura-bashi; I stopped about noon to lunch beside a stream which sparkled in the dappled sunlight filtering through the forest. When I had finished I followed the path, pushing through waist-high bamboo grass, to a collection of huts where I crossed the river by Myojin-bashi then, spurning a touting taxi driver, I walked the long 3 Km. of road to Kamikochi. After a wash in the river I joined the others for a meal at the fine new tourist restaurant, a substantial and reasonably priced meal of fish-and-vegetable soup, pork cutlet with salad and rice.

We then packed up and tried to set off; Day’s old Hillman was reluctant but after help from a bus crew—Japanese drivers are most helpful towards their fellow drivers in distress—we got away, Joe leading, Kevin and I tailing him. We stopped at Matsumoto Station, where we had agreed to part, Tom and Joe preferring to press on for home while Kevin and I opted for a night in a ryokan before driving back on Sunday. We accordingly returned to our hotel in the nearby spa and soon were enjoying a soak in the big tiled bath.

After a week of living out of our sacks we were ready for anything and hungrily tucked in to the varied and unfamiliar dishes set before us. (The Englishman in Japan normally lives in a little world of his own, living western style and eating western type food). Used by now to sleeping Japanese we spent a comfortable night and drove home next morning by way of Tokyo. This route took us between the Central and the Southern Alps and past Fuji-san, but it was a hazy day so we saw little of the hills.