Cave Exploration In South Wales

by D. M. Judson

(1) Dan-yr-Ogof

The spring of 1966 heralded the beginning of a new era in South Wales caving; our knowledge of the caves of the Swansea Valley and of the Upper Neath has been increased enormously and continues to increase almost weekly. The impetus given by the dramatic discoveries at Dan-yr-Ogof on Sunday, 20th March, 1966, has continued ever since. So much is happening, and at such a pace, that this report is likely to be quite out of date by the time it appears in print. However, I will attempt to relate the recent happenings and to precede them with a short history of the cave prior to 1966.

`

Exploration: 1912 to 1940

“Careful map study showed that beside the Mellte-Heppste-Upper Nedd region, there was a big rising at Dan-yr-Ogof near the head of the Tawe, the Swansea river, . . . [1]

Dan-yr-Ogof was first systematically explored in June 1912 by a party of local men, T. Ashwell Morgan, Jeffrey L. Morgan, Edwin Morgan and Morgan R. Williams (keeper) [2] They explored the enterance series and traversed three lakes in a coracle but were turned back at the start of “a watery passage”.

No further exploration seems to have been made for almost 24 years. It was in September 1936 that our own Ernest E. Roberts came to be walking over the Vans; he noted the major stream sink at Sink-y-Giedd and eventually came down the steep dry valley to the rising at Dan-yr-Ogof. He called at the Gwyn Arms and learnt of the 1912 exploits. He had been fired with enthusiasm!

The first assault came in May 1937; Roberts contacted Gerard Platten and G. S. Gowing and quite soon they were able to reactivate T. A. Morgan. After several trips throughout the summer of 1937, a fourth lake was found and crossed and a whole series of passages discovered beyond. Morgan, with Roberts, reached Shower Aven in September and on the final trip in October a party led by Platten penetrated a considerable way into the “Long Crawl”. They could hear a distant waterfall but found the going too tight to continue further.

Shortly after these exploits a new entrance was made above the river exit and the upper passages as far as Bridge Chamber were opened as a public show cave in the summer of 1939. The cave was closed at the outbreak of war and, due to a series of prolonged legal squabbles, was not opened again until June 1964.

The Present Phase of Exploration

An agreement was made between the South Wales Caving Club and the cave management shortly after the re-opening of the show cave. Thus began the present phase of exploration. Efforts were first concentrated on the river passages; siphons were passed in a side passage just prior to Lake 4 and access was gained to a fifth and to a sixth lake. A forty foot dive led to Lake 7, to date the farthest known point of the total Dan-yr-Ogof River.

A fair amount of scaling pole work and small-time boulder choke prodding was done in the summer of 1965, but it was was not until October that Platten’s Long Crawl again became a source of interest. The distant sound of falling water and the amazing strength of the outgoing winds made it a talking point in the Gwyn Arms throughout the winter.

It was on Sunday, 20th March, 1966, after a long wet winter had precluded entry to the system, that Eileen Da vies came to push the Long Crawl. Drawn through a series of sinuosities by the distant roar, she arrived at the head of a short pitch opening through the roof of a large sand-floored chamber. A small trickle of water fell down a tiny parallel shaft. The party possessed no ladders and were compelled to turn back. It was not until 12th April, Easter Tuesday, that the weather again permitted entry.

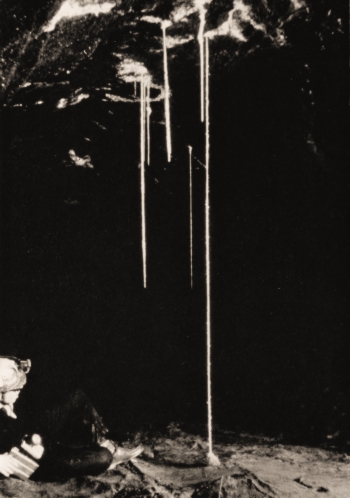

Miss Davies led a party of five through the crawl. An 18 ft. ladder descent brought them on to a sand bank at the side of a very spacious passage. Although they did not know it at that instant, over 1#half# miles of virgin cave lay ahead of them, just to be walked into! The first part of this passage became known as Gerard Platten Hall, after the man who had done much to inspire its discovery. Going left from the foot of the ladder they passed a great hole leading to a lower series of passages, and turned left at a beautiful crystal pool ten feet across, almost the width of the passage. Beyond a sandy section the roof lifted to over 30 feet and they followed the Grand Canyon, a meandering keyhole section passage about 150 yards in length. After a short bedding plane of stooping height they burst out into the Red Monk Hall. This was even larger than anything before it, superbly decorated with groups of pure white straws scattered at random across its arched roof. There were straws up to 10 feet in length.

More thrills were to come; a large boulder fall on the left and on the right a lofty aven containing a thundering cascade. A 15 ft. climb at the side of the boulder fall and they set eyes on a clear green pool; it disappeared round a corner, the walls severely undercut beneath the water line. It was said to be 40 feet deep but a recent survey showed the deepest point to be 8 ft. 3 ins. to a soft mud floor. They halted at this Green Canal, but investigated a hole through boulders to the left. Here was an enormous dull void, larger even than the Monk Hall. “The Hangar” was a great muddy cavern, 30 ft. wide and equally high, almost straight and finishing abruptly after 250 feet in an avalanche of clay and boulders. Taking the other passage at the Crystal Pool they entered Flabbergasm Chasm, a high level oxbow with breathtaking straw formations. They went on to have a quick look down the great hole, where they found a lower phreatic and very complex zone, before going out with the glad tidings.

Progress continued feverishly throughout the summer, when the weather allowed. The Green Canal was crossed, and a series of high passages led back to a river passage again, but this was a much smaller river with only a fraction of the flow seen in the Lakes. The river passage headed north, upstream, but after only 250 feet turned abruptly south west and finished in a sump. Above this ‘Rising’ the passage was at least 80 feet high, but no easy climb presented itself. A lower loop was found, with extensive ramifications; this formed a by-pass to the Green Canal. This was a region of relatively small streams and stagnant sumps and gave no clue as to the whereabouts of the main river.

Eventually, by combined operations on the week-end of 24th/25th September, 1966, the wall above the Rising was scaled. Once up the first 25 feet of open wall an easier rift climb was followed until entry was gained to a small windy crawl, ‘Windy Way’, at about 60 feet above the Rising. The winds here were stronger even than those previously encountered in the Long Crawl, a sure sign of further large passages. Down a rather tricky chimney, the party set out along a narrow rift passage, obstructed in places with large slabs of calcite, fallen from the vein along which the passage had been formed, and decorated almost continuously with myriads of tiny tortured helictites. The passage ended in a pitch. Through a narrow slit in the floor they peered down over 40 feet to where a stream flowed placidly in a large river gallery. This must be one of the most rewarding pitches in British Caving.

Downstream a large silent sump presented itself; upstream lay a river passage of majestic proportions. It continued for just short of half a mile, on an almost constant bearing of ll° North. This, the Great North Road, is a most remarkable passage, it is formed for most of its length along a number of mineralised fault planes. In two instances there are high caverns where fault planes are exposed for the full length of both walls.

There were many climbs made over or through mounds of boulders, often of dubious stability, followed in each case by a section of fine lofty river passage. After the last and largest of these boulder falls, which forms the termination of the cyclopean ‘Pinnacle Cavern’, the river passage leaves the fault line and takes off westwards. Two superb 180° meanders follow, before the passage again turns northwards and heads into its final catastrophic boulder fall.

On their way back the explorers entered a large high level oxbow to the east of the main passage. This turned out to be a calcite wonderland, ‘The Mostest’, with crystal pools and a continuous flowstone floor.

Over six months elapsed after the discovery of the Great North Road; the boulders were toyed with but did not yield. On 8th April, 1967, the writer traversed the Great North Road with a large party of visitors, mainly Northerners. After several hours in the boulder fall attempting to push the choked stream course, and later attempting to make a route through the boulders above it, I concluded, along with Edwards and Arculus, that the situation was pretty hopeless. We decided to have a second look at The Mostest on our way out. At precisely the point where everyone started to gaze down at the beautiful crystal floor, Edwards chanced to look up at the roof. He saw a spacious aven, previously unnoticed.

Within minutes the whole party had climbed 40 feet to the top of the aven and were making rapid steps along the high passage which lay at its head. We climbed over boulders and crossed deeply crevassed expanses of white sand before descending once more to the stream, now on the far side of the great boulder fall. Clambering over more rocks we suddenly burst out through the side of a large square passage. But here there was confusion amongst the pack; the passage looked equally promising left as right. Both directions were upstream! The party split; the right hand passage was followed as a low stream passage with some interesting high avens, but became impenetrable after 500 to 600 feet. It was the left hand passage that really produced the bonus.

Starting as a 20 ft. square stream passage, it became larger and larger until we were standing at the foot of an enormous boulder pile in a cavern 60 to 70 feet in width. The roof was just one bed of limestone, dipping slightly to the south-west. This was surely the largest expanse of cavern to be found in any of the South Wales caves, Agen Allwedd included. We pressed on over the boulder pile and across the deeply crevassed sands which overlaid it, into another boulder strewn passage. All the while the stream had been gradually fragmenting, with small inlet passages and showery avens. Whilst the passage size became larger, the stream became less. Clearly the passage must predate the stream which now makes use of it. Another 200 feet and we were halted by a great avalanche of mud and boulders spilling out from the roof. A more final end to our explorations one could hardly have conceived.

We looked more closely at a number of large avens on our return to the Great North Road. They all possessed great promise but none were free-climb material. All had heaps of rock at the foot, mainly sandstone containing large quartz pebbles. Some were several feet across, seemingly larger than the avens down which they had apparently fallen. These avens present a challenge, which at the time of writing still remains. Here perhaps is the opportunity to discover another overpass to an apparently final boulder fall; time will tell! The passages above and beyond the North Aven, discovered on 8th April, 1967, have now become known as “The Far North”. Because of their comparative remoteness they still remain very little visited.

A sketch survey is in existence of all the known passages, but this is for the most part only to C.R.G. Grade II or III, with distances paced out and rough compass bearings taken. In September 1967 the writer began the laborious task of producing a Grade 6D survey of the whole system. This work was started at Boulder Chamber in the 1937 section of the cave; an acceptable survey already existed of the earlier passages, from the entrance. By March 1968 the survey had progressed through the Long Crawl, across the Green Canal and had reached the Rising, the end of Dan-yr-Ogof II.

At this stage it was considered that, rather than flog in and out daily through the Lakes, the Long Crawl and the Green Canal, a better way to expedite the completion of the survey through III and the Far North would be to set up a camp at Bat Chamber, just before the Rising. This was optimistically planned for Easter. Through some strange miracle the weather co-operated perfectly and allowed the event to take place in full. The survey party spent five nights below and spent 4^ working days on the survey. The work through and over the boulders up the Great North Road proved to be a very slow and tedious task. While trying to draw accurate cross-sections, new avens and roof passages were found and entered and of course the survey halted while these were explored.

The most significant find was the “Pinnacle Spout Series”. A series of passages at various levels from 50 to 150 feet above the main stream level was first entered on 16th April, 1968, from an aven above Pinnacle Cavern. This linked with a large passage discovered next day which is really a continuation of The Mostest, leaving the main passage just above ‘The Spout’ and running first east, then south and eventually running into the north end of Pinnacle Cavern at a high level. The survey reached the top of North Aven, the start of the Far North, and that is still the limit to date (26th April, 1968).

In all, the Easter camp proved to be a great success. Thirty-three man-nights were spent below and, in addition to the survey and exploration, valuable water tracing and water analysis work was carried out, as well as Alan Coase’s photographic work. We had a telephone link with a strong and very valuable surface party and were greatly assisted by many members, and also non-members of the South Wales Caving Club.

The more that we find out about Dan-yr-Ogof, the more fascinating does the study become!

Bibliography :

|

Coase, A. |

June 1966. The Dan-yr-Ogof Discoveries. C.R.G. Newsletter, No. 101, pp. 22 to 27. Dec. 1966. Dan-yr-Ogof. Further Exploration. C.R.G. Newsletter, No. 104, pp. 6 and 23. Sept. 1967. Some Preliminary Observations on the Geomorphology of the Dan-yr-Ogof System. Proc. of the B.S.A., No. 5, pp. 53 to 67. |

| Coase, A. Lumbard, D. Roberts, E. E. Roberts, E. E. |

Jan. 1968. Dan-yr-Ogof. 5*. Wales Caving Club, 21st Anniv. Publication, pp. 57 to 73 and survey. 1938. Caves and Caving, Vol. 1, No. 4. 1938. Dan-yr-Ogof and the Welsh Caves. Y.R.C.Journal, Vol. VII, No. 23, pp. 52 to 61 and 85 to 86. 1947. Dan-yr-Ogof. Y.R.C. Journal, Vol. VII, No.24, p. 181. 1949. Fluorescein Results. (Dan-yr-Ogof—Sink-y-Giedd), Y.R.C. Journal, Vol. VII, No. 25, p. 274 |

(2) Ogof Ffynnon Ddu—Britain’s Deepest Cave System

After many years of speculation and effort by members of the South Wales Caving Club, Ogof Ffynnon Ddu II was entered from Hush Sump on 24th July, 1966, by a party of four divers. A complicated series of passages, shafts and boulder chambers was traversed before rejoining the main stream. Several long and gruelling dives were made subsequently, in which the stream passage was followed for over 2700 yards to a 20 ft. cascade and eventually a constricted bedding plane sump.

Magnetic location checks were made in a large boulder cavern, the Smithy, in the new series. This established a horizontal distance of only 130 feet between the Smithy and the great boulder fall at the end of the Cwm Dwr Quarry Cave.

A dry connection was briefly established with Coronation Series in Ogof Ffynnon Ddu I, but after several untimely collapses and some very near misses on personnel it was thought best to leave this alone.

In April 1967 the predicted connection with Cwm Dwr (Jama) was made and tourists trips up the new stream passage became a regular thing. A few weeks later, after several maypole attempts towards the top end of the stream passage, a small tributary stream passage was entered at about 80 feet above the main stream. This was the start of the discovery of an extensive maze of high level passages, now known as the Clay Series. In order to make further progress in the Clay Series trips of 16 hours and more were becoming necessary, and arduous trips at that.

After concentrated efforts in May and June 1967 (particularly a 38-hour camping trip), clues were picked up in one of the larger passages in the Clay Series, in the form of snails and flies. Action with the magnetic device followed swiftly and produced the astounding result of 15 to 20 ft. cave to surface! A very exciting day’s digging and the new entrance became a reality.

With the new entrance in use, exploration of the Clay Series could be carried out in comfort and leisure; the first priority being to re-discover the stream beyond the top sump. In the autumn of 1967 a way was pioneered north-eastwards, up boulder slopes, down boulder slopes and along some interesting traverses, to reach the stream once more; O.F.D. III. After a couple of cascades had been traversed at the outset, the route became a large meandering river passage mostly 80 to 100 feet high. The old dream of a connection with the Bifre looked like becoming a reality. However, after following this fine stream passage for about 600 yards, a large boulder cavern was found. The stream issued quietly from the base of the boulders. The cavern contained great quantities of silica sand and large sandstone pebbles. Is this cavern directly beneath the Bifre? At the time of writing nobody knows the answer to this question; attempts with the magnetic location device have so far proved negative.

The connection between O.F.D. I and O.F.D. II in the Coronation Series has collapsed again of its own free will. Trips have been made from Clay Series Entrance, up to the final boulder chamber in II, down the stream in II and out at the original entrance to I, by Grithig Farm, a vertical traverse of over 800 feet.

Little did Ernest Roberts or Gerard Platten realise with their meagre discoveries at Cwm Dwr Quarry Cave in 1937 and 1938 that they were sitting on the key to Britain’s deepest cave system.

(3) Little Neath River Cave (Bridge Cave)

Dismissed in two lines by Roberts after his visit there in May 1937; “At the Pwll-y-Rhyd bridge we were disgusted by the quick finish of the Bridge Cave, in which we heard water loudly.” [3] From a shake-hole on the east bank of the Upper Neath, within a few yards of the bridge, 50 yards of passage ended in a sump. In normal weather the River Nedd disappears in its bed a few yards below the bridge and in dry weather a good way above the bridge. This was all that was known up to January 1967.

On 28th January, 1967, three members of the University of Bristol Speleological Society dived the terminal sump in Bridge Cave. After 150 feet they emerged into a large stream passage, which they followed for almost a mile to another sump. Subsequently an inlet passage to the east was followed for about 1000 feet to tree roots and then daylight. The new entrance, now known as Flood Entrance, is a few inches above the normal river level, on the east bank about 200 yards above the bridge.

In all 12,000 feet of passage have now been surveyed, Sump 2 has been dived, 150 feet, followed quickly by Sump 3, 240 feet, with 150 feet of large river passage before a fourth sump.

This is now a very fine example of an active river cave and is easily accessible to non-divers in reasonable weather conditions. It seems to have much in common with parts of Goyden Pot and New Goyden Pot in Nidderdale.