Damavand And Alum Kuh

by Glyn Edwards

Damavand is an extinct volcanic cone 5,671 metres (18,600 ft.) high and lies in the sun some fifty miles east of Tehran from whence it can easily been seen in the morning.

Peter Standing, Peter Livesey and I left Tehran during the heat of mid-day. Steven Craven had kindly offered to take us to Damavand in the expedition Land-rover, accompanied by Harvey Lomas. The road to Abe-Ali was taken and soon the hustle of Tehran was left behind in the dust of the road. Beyond Abe-Ali we slowly crawled behind huge ‘Macs’ up a winding pass. The Iranians were busy erecting snow tunnels over the road which is the main route to the Caspian Sea. The top of the pass offered a superb view of the volcano and we took the opportunity to photograph it. From here the road dropped steeply down to the village of Polur, where the main road was left and we ventured into a complex of dirt tracks. As usual the wrong one was taken and we eventually ended up at a Kurdish village on the west side of the mountain. On our left the fabulous Yakhar river flowed 1,000 ft. lower down in its gorge between us and the lesser peaks to the west. The usual route starts from Reyre on the east side. Obviously we were off route but we decided to attempt an ascent by this unfrequented west route because of the late hour. We could see the summit and the way up seemed straight forward. From the village we plodded up a dusty zig-zag track steeply, wondering which way W. T. Thomson climbed when he made the first ascent in 1837.

We walked for two hours until the shadows of darkness overtook us. So far we had seen no water, running or still, so our pint and a half was rationed until we did. A fairly comfortable night was spent bivouacked inside a ring of stones. In the morning we were up before the sun had climbed into the sky and a long thirsty ascent followed. Soon we left the steep valleys at the base of the mountain and ventured onto the cone itself, walking, scrambling up cindery scree. It was not altogether monotonous for as the air became colder and thinner the view became proportionately finer—all the more reason to stop and rest. Around lunchtime we thirstily arrived at the snowline where we dined on the crystal water and rested. The volcano was beginning to look more rugged and mountainous with the advent of the snow. We climbed up a series of small snowfields, where the sun had serrated the snow into a sort of staircase. There was the odd rock to scramble up as well as deep snow in places and we arrived on a rocky shoulder which we estimated was no more than 3,000 ft. from the summit. It was here we intended to spend the night as one is supposed to visit the top only in the morning because of the sulphur fumes—the springs are activated by the sun and presumably frozen at night. We spent the rest of daylight shelter-building and cooking until the sun dropped low and water began to freeze. The wind summoned gusto for its nightly dance—a signal to hide deep inside sleeping bags and wait for the reinforcements of dawn. Livesey awoke us in the morning with lifegiving hot lemon tea and so we broke the ice enshrouding our sleeping bags and slipped on frozen boots.

We climbed a steep snowfield capped by frozen rocks chilled by an icy wind, thinking that for the ascent of high mountains one should be properly dressed with windproofs, balaclava and duvet. We reached the sulphurous yellow rocks of the summit with surprising ease. It was really an anti-climax. We traversed around the snow-filled shallow crater, the cold stinging and obliging us to shelter behind rocks wherever possible. We saw pumice stone and the sulphur springs smoking, but did not inspect them too closely. The view was hazy but gave an impression of height. One remarkable sight was the shadow of Damavand thrown miles onto the western hills—it was a perfect triangular cone and we looked to find our own shadows on top of this! We were glad to descend and decided our route was dangerous without ice axes. We paused for a meal at our shoulder bivi and carried on down into the heat. We got a lift and were in Tehran that same evening.

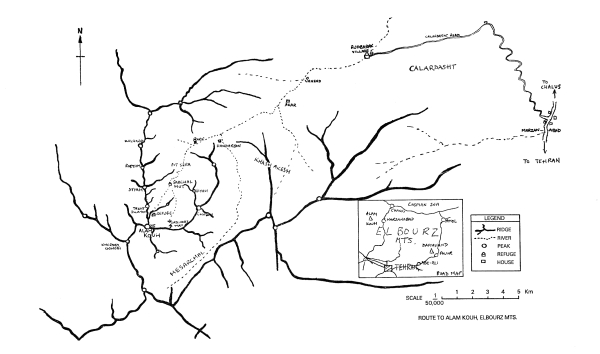

The day after Damavand Standing and I contacted the Iranian mountaineering federation. They supplied us with a map and information about Alam Kuh (about 14,000 ft.). We decided to attempt the German route which is the large buttress to the right of the North Face. We could then do a traverse of the summit ridge and descend by the ordinary route. We were assured that this was a rock route with some pitches of grade V but mainly III and IV, and that a bivi would be necessary on the way down.

That afternoon we were on our way to Marzan Abad by bus. We arrived there at dusk and had the greatest difficulty finding transport to Rudbarak. A bus took us to Calardasht where we eventually slept in a kindly two-roomed house owned by a little man and his family, the only furniture being superb carpets and bedrolls. A small pipe-stove warmed a corner of the other room, into which moved all the lovely children and their good parents. It is quite futile to travel by night (unless, of course, already booked).

We rose early and walked to Rudbarak, arriving there at eight o’clock. We found the mountaineering federation hut, where we had intended to spend the night, but a large sign deterred us from entering. It was the price list for guides and pack mules—very expensive—and we hadn’t the time to explain that we wanted neither. We walked some two miles beyond Rubarak on a good track (suitable for cars) before it turned into a footpath. The houses were built of logs and Standing said they were similar to the sherpa’s homes in Nepal, and occasionally there was a modern bungalow—the holiday or summer house of the Tehran rich, newly built. In the narrow valley, washed by the fast flowing glacial river, we stopped for breakfast proper, where we found a dead porcupine in the lush grass. Cattle wandered freely and there were many herds of sheep looked after by goats and small boys. We continued beside the still rushing waters following the deep valley. Seemingly we made good progress but we had not yet begun to climb. At Mandaboro, where a bungalow lay, pointing the way, we followed the right hand fork in the river and left behind the last homely house. We traversed the shoulder of a fairly deep gorge and below us the river fell in cascades. Steeply now, climbing, packs growing heavy. Surprised, we came upon men with strange hats (like Hendrix sheepskin wigs of varying colour) dipping sheep into the river. We zig-zagged up the valley side beginning to feel very tired. The last section from Marir to the Sarchal Hut is very steep and rugged. Time to rest, and we arrived at Sarchal after nine hours’ hard walking which I consider good time (Iranians allow twelve hours). The hut is little used and in bad repair but we made ourselves at home and cooked dinner. Afterwards soon retired with thoughts of a pre-dawn start and the German route.

It was quite light as we ventured out in the morning. A petrol stove fire all ablaze delayed our departure and nearly destroyed the hut. On our sacks we carried bivi gear, climbing gear and food; in our hearts, joy, of walking on the wildside. The terrain was rugged moraine boulders as we forced a way directly towards the junction of a low ridge with the main face and the start of the German Route. It took nearly two hours to reach the ridge top, the rock was shattered and extremely loose. The ridge itself proved hard going with tottering gendarmes and gaps but we were presented with a magnificent view of the North Face and the ice field sweeping away from its foot. The sun just peeping over the top causing minor avalanches. Directly below we could just discern the ‘Refuge’. We continued, free climbing easy slabs and all of a sudden we knew we were on route. We passed belay slings and a large blue arrow accompanied by Iranian graffiti. We concluded that this must be a ‘trade route’ for artists. A wall presented itself, so we had second breakfast on a convenient ledge, then roped up. Standing led off, it was a v.s. pitch on remarkably good rock, just being warmed by the sun. I led through, the climbing was superb and the next pitch was topped by an overhanging aid move well supplied with slings. Superb, with birdseye view of snowfields down below. Life is good. The next pitch was disappointing, just scrambling, so were the next three or four rope lengths. We didn’t mind as rapid progress was made. Obviously too rapid, for I led off round a corner into a couloir where the sun never shines it was plastered with powder snow and underneath in some places, ice. It became very cold and unfriendly; progress slow and painful without gloves or axes. We seemed in a dangerous situation, even when I arrived at a reasonable belay, for the next pitch necessitated a traverse across the couloir. With aching fingers and fear I watched Standing proceed carefully. He was across and I joined him, snow biting fingers, frightened. The difficulties eased, and soon we were able to laugh again. About six or seven more 150 ft. rope lengths saw us on the summit ridge. There was one pitch with an easy tension traverse and a few others of interest, otherwise the climbing was around V. Diff. The sun shone on the summit ridge and the other side plunged away in a mass of boulders, screeing down to distant snow fields. The summit itself was a mass of tottering blocks and rocks and here we lunched as it was 1 p.m. Afterwards we traversed along the rotting ridge towards the ordinary route which we were to descend. The day was not yet won and the descent proved, in many ways, more hair-raising than the ascent. We dropped onto a shoulder and then into a world of splintering spires dissected by splintering gullies. A gully was chosen and we descended, delicately, the objective dangers being great. A rope was not used as no belay was sound. After what seemed a long time a scree run was found which deposited us on hard snow and we were then soon walking across the icefield towards the Sarchal Hut.