Spitzbergen

by Duncan Mackay

There was a great graunching sound as the propeller hit the bottom. The next wave carried the inflatable onto the rocks that stood like a row of teeth along the shore-line. By some fluke the boat did not puncture and we managed to scramble ashore practically unscathed. We were the scientific team of the Leys School Spitzbergen Expedition, arriving at our study area at the mouth of Gipsdalen. This was a continuation of our experience of the immediate past and an omen of what was in store for us. We had left London airport in a thunderstorm, our little DC9 flying through dark storm clouds amidst great flashes of lightning. As we flew north from Norway the whole of the Arctic was clothed in cloud as bad weather moved up from the Atlantic. Our landing at Longyearben was a little dodgy. The plane was the largest ever to have attempted a landing and theoretically the runway was barely long enough. The pilot slammed the plane down with a crash and slewed through 90° as the end of the runway and the fjord loomed closer. We were all very relieved to get on to terra firma, though we were still only half an expedition. The airline company had messed up our bookings, and as a consequence only twenty of our forty members had come on this plane. The rest were to follow on the next available flight. Our plans were modified to accommodate these changes and Ray Ward our leader altered his master plan to ensure that the flow of essential supplies suited this situation.

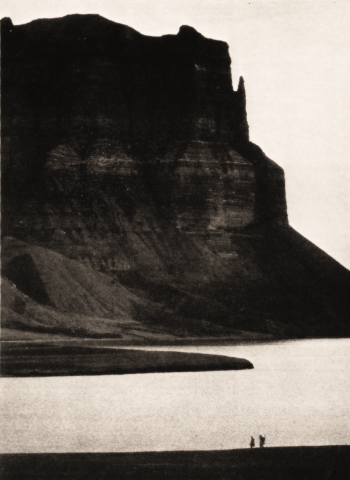

Ray was an economist by trade and the masterplan was a glorious tangle of technicolour arrows passing between squares which represented phases in the expedition. The master plan gave the ten members of the scientific team the first week in Spitz to complete their study of the vegetation of Gipsdalen. The supply team would continue up Isfjorden and prepare supplies at our main base camp, Brucebayen, ready for the arrival of the remainder of the expedition and also for our sledging trip across the icecap to the Atomfjellet peaks. A converted trawler called Copious had carried us all from Longyearben and now it chugged away from Gipsdalen, leaving Richard Hocking and me to run the various projects. Richard was an instructor from Brathay Hall and had a good knowledge of mountain plants in Britain. I had read a lot of papers on the arctic flora and between us we hoped to cope with the identification of most of the plants. Our main project was the mapping of the types of vegetation in the mouth of the valley. We hoped to find some pattern in the distribution of the plants which could be explained by the environment of the valley. Our site was ideal in every way. The little trappers’ hut on the headland gave shelter for cooking and driftwood on the beach provided fuel for the fire. We had a freshwater spring only, a few yards away and could walk easily to Brucebayen if the need arose. Across the bay Temple mountain towered above the blue water of the fjord.

Our week went quickly and we rapidly found that we had undertaken more than we could deal with in the time available. The plants were all new to us and quite unlike anything we had seen before. Some of the species did not occur in Britain and those that did were inevitably great rarities. It was with some amazement that we discovered that the buttercuplike plant, found growing in the marsh near our hut, in a great yellow carpet, was none other than Saxifraga hirculus. In Britain it is recorded in only a few sites, and is a real rarity, yet we found it everywhere in Gipsdalen. The same was true of the Oyster plant, which pushed its little blue flowers through the debris all along the tide line. Some of the plants, particularly the mosses, we could not identify at all. These we collected and brought back to England to study.

Amongst the moraine we came across other inhabitants of the Tundra. Ptarmigan squatted between the rocks feeding on Dryas octopetala, the mountain avens. Whole families of these birds allowed us to walk up and photograph them at close range . We found signs of arctic fox long before actually seeing them. Dead guillemots and scraps of fur showed where these voracious carnivores had made a kill. Yet they seemed far more wary of our presence than other animals and we only caught glimpses of them in the distance. Reindeer were the only large animals that were present and their antlers littered the beach. We came away with a number of fine specimens with as many as twelve points.

Other studies included the collection of invertebrates from the bog pools, the measurement of energy capture by algae in the various freshwater pools and a host of observations about the environment generally. Each evening we returned from some part of the Gipsdalen valley with bags of samples and further recordings. We relaxed around a driftwood fire and talked about the day, the place and the future. We wrote our feelings and the events of each day in our diaries; even those not normally accustomed to such pastimes had so much to remember, there was no alternative but to take some notes. Our food was also eaten around the fire, as the hut was far too small to hold all ten of us. Pieces of driftwood were used to form a barrier against the wind that blew from the north, cold heavy air chilled by the icecap.

Copious returned at the end of our week, bringing the second half of our party, fresh from England. She anchored off the headland and the inflatables came over to collect us for the next stage of the expedition. We had spent a happy and relaxed week at Gipsdalen and would have liked to stay longer. Yet the lure of the icecap drew us away and up to Brucebayen. On board Copious once more we all chatted furiously, the news from home, our adventures, the flight up, all came out in a bundle of eager words as the Nordenskiold glacier drew nearer.

Ferrierfjellet and Terrierfjellet, the twin peaks at the head of the glacier, guarded the route on to the icecap. In several days we were to haul our sledges past these peaks and on to the main ice fields that lay between them and the Atomfjellet range. This range of granite peaks lies in the middle of the icecap and contains the two highest mountains in Spitzbergen —Newtontoppen and Perriertoppen. Ray was pleased to announce that the supply team had done their stuff and established Half Ton Depot at the foot of Ferrierfjellet. We had several days to transport the remaining supplies up the glacier before setting out with the sledges.

At Brucebayen we found the supply team living in the luxury of four wooden huts, built at the turn of the century by the Scottish Spitzbergen Syndicate. They had come to Spitzbergen to prospect for coal and had drilled a number of bore holes close to huts. They did not find the coal seams that they had hoped for and left at the end of the first winter. Remains of their prospecting still lay around Brucebayen, even the old gas engine that powered the drilling rig stood rotting in a hut with its gas plant. Between the huts and the beach a small length of railway track survives. We made use of the little trucks to bring our gear up from the beach.

The huts had been repaired by the supply party, the leaks in the roof of each hut patched up with roofing felt. In the communal hut a log burning stove brought the temperature to an uncomfortably high level, that induced a drowsiness in the occupants. It was always a hard task to brave the rigours of the outside world after a snooze in the mess room. But wood had to be collected, supplies sorted, loads packed and the general odd jobs around camp finished. At the end of the day the large dustbin full of hot water, heated over a wood fire, gave us our first opportunity to get clean in comfort. Then to sleep in the spacious luxury of the wooden huts.

The carries up to Half Ton Depot were completed in two days. We then established our first ice camp below Ferrierfjellet about ten miles from Brucebayen. The intention was to load up the sledges here and haul them up the ice ramp that led to the flat ice fields beyond. Unfortunately we soon found that the hummock ice at this low level made hauling impossible. So the supplies were unloaded and carried to better terraine higher up. We had not expected the difficulties to begin so soon and when we found that the sledges would only move on the steep ramp, with twelve people pulling at once, we became seriously worried about our prospects. The ramp took three days to overcome and we were only four miles from Half Ton Depot when eventually the sledges began to run smoothly.

Ray decided that something had to be done to catch up with the schedule on the master plan. We had no hope of completing the Atomfjellet traverse unless we could make up the time we had lost. Eventually the party was split in two and a climbing group was sent ahead to establish a base camp at the start of the traverse. The remaining group would follow behind more slowly with the bulk of the food supplies.

One Two Three Heave …. became the familiar cry as we started our overladen sledges. A big initial tug set the load in motion and as long as it kept moving a much smaller force could be exerted. But inevitably somebody stumbled or the sledge hit a bump in the ice. Everything would come to a sudden halt and had to be set in motion again. In this way we slowly made progress, stopping now and then to eat or rest for a few moments. Each sledge was pulled by three people, the fourth member of each team walking behind and pushing when necessary. In this way everybody had a break at regular intervals.

Two events stand out from this period, which was otherwise just a matter of plodding onwards into the white horizonless mist ahead and setting up camp each evening. Both events occurred close together, though they were not really related. The first was the sighting of two Russian helicopters, flying low across the ice. We had no idea what they were doing up on the ice cap until we got over the next rise in the’ ice. We saw a small hut which was evidently being evacuated before our arrival, though we never discovered what it was used for. At about the same moment as the helicopters appeared, a figure came skiing towards us from the horizon. We assumed that this was a Russian coming to see what we were doing. We were quite wrong. The figure turned out to be a Japanese explorer who was completing a solo traverse of Spitzbergen. He had been alone on the icecap for three months and in Longyearben they had assumed he was dead. As he came towards us exposing his teeth in a broad grin, it was obvious that he was in very good shape. He marvelled at our overloaded sledges and wondered how we could pull them along at all. Then after he had photographed us we exchanged some Mars bars for some Japanese sweets and went on our way.

After three days’ hauling over more or less flat ground, the ice began to rise upward, slowly at first. Then suddenly it steepened and we could go no further. This was the start of the Atomfjellet peaks we reasoned, not knowing our exact position on account of the thick mist which had not cleared for several hours. We turned to the west and contoured along the side of what we assumed to be Saturnfjellet. After two further changes of direction we calculated that we must be under Jupiterfjellet and in the area where we intended to site our ice base camp. Everywhere the ice sloped away to the west and it was with some difficulty that we found a camp site which, though not perfect, was adequate for our requirements.

We had attempted to make radio contact with Ray’s party every evening. But we had had no success whatever in contacting him. Just as we were sitting down to our reconstituted beef stroganof that evening, the radio in the back of one of the tents crackled, followed by an indistinct voice: “Come in, Lima Hotel Sept Severn Juliette, this is Lima Hotel Sept Severn India.” Ray had at last made contact by mistake. We greeted him warmly and gave our position. “In that case we should be with you in twenty minutes” came the reply. We put on an extra brew and waited for their arrival.

The next few days were a real trial, as the weather worsened and we saw our chances of completing the traverse diminish. Snow, driven by a strong wind from the north, fell continuously. The whole camp vanished as several feet of snow built up around the tents. The wall we had constructed against the wind simply collected snow which pushed in on the tent walls. Periodically we had to dig this snow away as the tent walls sagged inwards under the weight. The penalty for failing to do this was ultimately the collapse of the tent. Several tents suffered in this way and the occupants had to move in with neighbours. All the movement in and out of the tent door let out the warm air and allowed flurries of spindrift to enter. Our problems were made worse by the fact that we were sleeping in hollows. The ice directly below each sleeping place melted leaving a depression in which condensation collected. Our sleeping bags became soggy and we became cold.

The storm left us as quickly as it had come. After three days a pale weak sun filtered through the mist. The first priority was to dig out the food supplies and search the snow for buried equipment. We dug out the collapsed tents and salvaged what we could of their buckled poles. Several people working along the lines of “When in the Arctic do as the

Eskimos do” built two large igloos. Inside we managed to fit twelve people for lunch. The thick walls cut out all sounds from outside and we had at last a quiet sanctuary from the howl of the wind and the flapping of canvas.

The time had come to make a move and attempt to climb at least a few of the surrounding peaks. Eighteen of us set off to climb Newtontoppen and the sun came out from behind its haze just as we crossed the col above our camp. A glorious view opened out in front of us—Phoebe, Jupiter, Wainflete and Astronom lay on either side of this remote and icy valley. Ray decided to go back to camp and persuade the rest of the party to come out with us as well. Meanwhile Steven Bugg and I climbed Jupiterfjellet and gave the Y.R.C. flag, that his mother had made, an airing at the summit. When we returned Ray appeared over the col bringing the rest of the party and a sledge with spare equipment.

Our journey to the summit of Newtontoppen was a shattering experience. Everybody started off in a poor physical condition, having spent long cold hours sitting out the storm. The mist didn’t take long to return and with it that cold wind from the north. I climbed the final snow slope to the summit relieved that it was all over. In fact our problems were just beginning. Jerry Jason, a student from Oxford, had become very cold and now he was unable to stand upright. Several of us carried him back down to the sledge whilst Ray waited for the tail end of the party. Somehow in our effort to help Jerry we managed to miss the top of the snow gully that led to the glacier. Our detour took about an hour longer and by the time we got to where the sledge should have been the rest of the party were about a mile away heading for home. They assumed that we were ahead of them but fortunately noticed us before it was too late.

We put Jerry in a sleeping bag and tied him to the sledge inside a bivi bag. Eight of us hauled the sledge whilst the rest went on ahead. We reached the first col and stopped to eat some of our meagre rations. Ray worked out a short cut across Fantastiquebreen, a quicker route to the camp. So we cut between Wainflete and Jupiterfjellet and then turned south. Continuing until we estimated that we should be close to the camp, we then spread out and searched for signs of the tents. We found none. Further on we tried the same technique, with the same results.

Now we were really in a bad way. Almost all of our food was gone and so was our strength. Fortunately we all carried sleeping bags and bivi bags so we stopped to get some rest. Two hollows were dug out of the snow slope and in these we waited, hoping that the mist would clear. We lay there for several hours as water trickled in and fingers of cold came up from below. Our plan was to remain where we were for twelve more hours and then, if the weather didn’t improve, we would head south and search for the camp in that direction. As we made this resolution our prayers were answered. The mist cleared for just a few moments. Huge towering cliffs were exposed that could only belong to Eddington riggen. This was exactly the information that we needed. We now knew that we were three miles to the north of the camp and we set off at once.

We found the tents without much difficulty and everybody was relieved when we arrived. I can remember sitting in a tent and being fed Ryvita butties with golden syrup and endless mugs of tea, feeling lucky to be alive.

Nobody wanted to stay much longer in this uncomfortable place. We spent a day resting and then began the long journey home, looking like an army in retreat. It was only when Terrierfjellet appeared on the horizon that our spirits rose and we hauled our sledges with enthusiasm. But the icecap was to play one last mean trick. We tried to cut down between Terrierfjellet and Ferrierfjellet, in a direct line towards Brucebayen. The first obstacle in our path was an area of soft slushy snow. We floundered for several hours before escaping from the other side. Then after running down a steep ice slope, we found ourselves hemmed in by crevasses covered with unstable snow. We were forced to leave the sledges and head on down to Brucebayen.

Half the expedition were now due to return to Britain and Copious lay anchored off Cape Napier waiting to take them to the plane. For the rest of us who remained the rescue of the sledges occupied some of the final week. A small group also managed to visit Gasoyane, the small island home of many sea birds, in the middle of Isfjorden. My final two days on Spitzbergen were spent photographing puffins, purple sand-pipers and arctic plants. These two days were pure delight, without responsibilities, surrounded by the beauty of unspoilt tundra.

In complete contrast, two days after leaving the rocky beach of Gasoyane, we were stuck in a traffic jam, trying to get out of London, in the sweltering heat of that “seventy-six” summer.