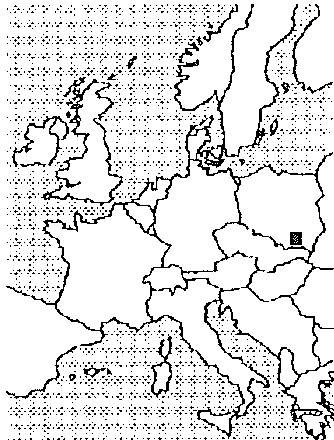

Polish Tatras

Ken Aldred

Anyone considering a change from the Alps may be tempted to visit the Polish Tatras. This part of the Carpathian Mountains has much to offer the walker who is content with the relatively low altitude. My wife and I had a botany trip in June, our choice of tiirring made with the intention of seeing the wide range of Alpine flowers. Unfortunately, it also corresponded to a veiy wet spell; heavy, vertical Tatra rain being indistinguishable from that of the Alps. We were advised that August was a better month but the problem then would be that the area is extremely popular and the prospect of joining a queue in order to chmb a mountain does not appeal.

Covering 27 x 10 km, it is a very compact area and is provided with numerous well marked footpaths, most of them colour-coded to match the information given in the cheap maps and guide books available in Zakopane and Kuznice, the two larger towns on the Polish side of the border.

The whole of the Polish Tatras lies within a National Park and enjoys the protection of extensive legislation. Visitors are not allowed to stray from the footpaths although it is possible to obtain chmbing permits for the granite, but not limestone, areas. Some of the most attractive parts he along the ridges separating Poland from Slovakia. Here walkers approaching from either side meet along the top and mingle quite freely, but are obliged to return to then own side of the hills at the end of the day. Parties of ten or more must employ a guide. Apparently, large parties are not allowed to get lost but smaller groups are not restricted by this bureaucracy. YRC groups could do then usual things.

We used several centres, the first being Schronisko Chocholowskie, a mountain hut built at the end of a metalled road in 1933. From the large stone-built hut a pleasant path climbed steadily through trees to a col, Grzes, then south along a broad grassy ridge to the peak Wolowiec (2063m). Primula minima was the most common flower along the ridge with dwaif pinus mugo providing scant protection from the elements as its maximum height was rarely more than a metre. There were many fine ridges and peaks to be seen from the summit, some of them over the border in Slovakia, but all promising more interesting days in the hills. In the meadows on the way back to the hut were the usual profusion of flowers, but none more colourful than masses of bright yellow caltha palustris, the common marsh marigold.

Our last centre was at Schronisko Morskie Oko, another large stone mountain hut built in 1908 above the lake of the same name. The weather was riot kind and we saw very few of the tops, and those seen were for a few seconds only as the clouds or mist parted for a fleeting glimpse. A path leads round the lake and climbs alongside a series of waterfalls to the upper lake of Czamy Stow pod Rysami. Continuing in the same direction for about three hours would bring one to the summit of Rysy, the highest summit in Poland, requiring ice-axe and crampons early in the season but infinite patience later in the summer when queues form below the surnrnit scramble. From Czamy Stow we climbed south towards the summit of Kazaluica but a mixture of sleet, thick mist and many alpine plants persuaded us that the saddle of Mieguszowieka would not offer us any greater satisfaction had we canied on.

The people of Southern Poland, whilst not being unfiiendly, do not greet visitors with the same enthusiasm as encountered in other parts of Europe. Perhaps then-experience of foreigners over the last 60 years gives them good cause to be wary but the best we could say about our reception was that it was of indifference to them. However, the exciting scenery, picturesque villages, (not the chocolate box Swiss holiday resorts), and the beautiful city of Krakow, an excellent starting point to the holiday, made this an area which can be safely recommended.