The Ogre

by Clive Rowland

At 23,900 ft. Biantha Brakk, or the Ogre, as it is known in climbing circles, is the highest peak in the Biafo glacier region of the Karakoram.

Although the glacier had been tramped several times by Westerners in the last 100 years and mapped by Shipton’s party in 1938/39 very little was known about individual peaks and good photos were virtually non-existent. In the late fifties Pakistan closed the area to foreigners and it wasn’t until 1970 that it was re-opened.

In 1971 I was a member of the Yorkshire Karakoram Expedition. We applied to attempt Gasherbrum IV, then the highest unclimbed peak in the world. Three weeks before we were due to leave Britain we learned that our application had been turned down but we could attempt Biantha Brakk, “if we wished.” The next two weeks were frantic to say the least, meetings with Shipton and others who had been to the area and visits to the Alpine Club library. All produced surprisingly little. One photograph taken about 1610 from 1,000 miles away on a Brownie! However from information gleaned it seemed that the North Ridge was our only hope as the rest of the mountain was “appallingly steep.”

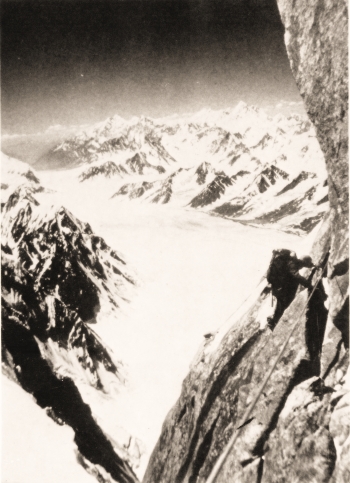

My first view of the Ogre came after six days of walking. First we walked along the Shigar and Braldu valleys for five days and then during the first day on the Biafo there it was. Most of the south side could be seen. Magnificent granite walls, beautiful blue ice and steep, steep snow.

After another two days’ walk we bypassed the South Face and carried on up the glacier to Snow Lake. Here we turned right and headed for the North Ridge. We never did reach this ridge. After days of floundering in wet, often chest deep snow, falling into hidden crevasses and rivers, we gave up.

Our only hope was to return down the Biafo and look for a route on the South Face. After negotiating the tortuous Uzunn Brakk Glacier the whole of the south side came into view—it was indeed incredibly steep apart from one weakness. A 3,000 ft. spur, rather like one of the Brenva Face routes, ran to a huge saddle (S.W. Col 20,500 ft.); from here the angle eased slightly and there looked to be several possible routes to the top. Unfortunately my enthusiasm for a “go” wasn’t shared by the other team members and we came home.

In 1975 another British team attempted the Ogre from the north, but alas they shared the same fate as ourselves. They failed to reach the ridge because of the atrocious snow.

Doug Scott, Ronnie Richards, Rob Wood and I met this team on their way out in Askole, the uppermost village in the Braldu Valley. We were on our way to attempt the beautiful 21,000 ft. Sosbun Brakk also on the Biafo. “Well,” I told the lads, “after we’ve dealt with Sosbun let’s do a proper recce of the Ogre’s South side. I’m sure it’s the way it will go first.”

No, we didn’t deal with Sosbun Brakk, it’s still not been dealt with. Have you ever tried swimming up a glacier with 70 lbs. on your back? We did and our three porters (Crosby, Stills and Nash) did and they couldn’t even swim. After three days and still a mile from the peak, we conceded and returned to drier lands. At this point our Balti friends decided to desert us. Of course we couldn’t blame them—we didn’t pay ’em either.

For four days four men ferried forty kilogram loads. They were fed up! A camp was set up on the Uzunn Brakk at about 15,500 ft. from which we intended to recce the Ogre and attempt some of the beautiful peaks to the south.

A majestic 20,000 footer which we named the Biafo Spire was attempted by the four of us. Being opposite the Ogre and offering what promised to be excellent climbing it was an obvious choice. We climbed alpine style and carried no tents. Digging snow holes was hard work but they are usually warm and safe. I don’t much care for camping on those big eastern hills. They have a tendency to keep falling down carrying tents and occupiers back to base which, when one is intent on going upwards, is a bit frustrating.

At the end of the second day’s climbing a storm blew in. We were only about 800 ft. below the summit but had to retreat. This venture had not been in vain however—from our high point we ascertained that indeed the centre one of the Ogre’s three summits was the highest and there was a feasible route to it.

Six days of snow and a million brews later, found Doug and I up under the Ogre’s south face oggling and boggling at the magnitude. “Shall we have a go?”—eventually—”No, we’ll come back in ’77.” It was during this walk about spell that we decided to have a closer look at the Lattoks—three superb mountains between 22,000 and 23,500 ft. Not thirty minutes walk away from our camp was the conflux of the Uzunn Brakk and Lattok Glaciers. There to our amazement, tucked in the V of the Junction was a beautiful alp, an oasis amidst all this rock and ice. Gentians and edelweiss were everywhere and a crystal clear stream flowed through the meadow into a small lake.

“And to think, we’ve been camping on bloody ice for three weeks,” I remarked. Doug and I and my piles were pleased with this find; it was an excellent site for our future plans.

Later in ’75 and again in ’76 Japanese teams attempted the Ogre. The latter attempt reached 21,000 ft. and their route to the South West Col was via the same spur we recced the year before. Good news, at least the Ogre’s lower half will go. Bad news, they had two camps swept away by avalanches! —Good news.

Doug and I picked our team carefully. Chris Bonington, because he could get as much free Bovril as we’d need. Mo Anthoine because he manufactures ice axes and other useful gear. He also knows everyone at our embassy in Islamabad. Paul (Tut) Braithwaite because he has a gear shop and he’s a painter and decorator by trade, which would be very handy for marking a route up the glacier. Finally Nick Estcourt because he likes Bonington and Bovril.

The 10th June ’77 saw us setting up base camp. It was pleasing to realise the Japs hadn’t found the meadow during their two previous attempts. Not a can or grain of rice to be found anywhere. Captain Aleem, our Liaison Officer was very pleased for just round the corner were the British Latok team. Their Liaison Officer and he were old friends. I was happy too, all this team were from Sheffield and I’d known and climbed with them for years. On the 12th, Doug and I started to blaze the trail to advanced base. It was still early in the season and the deep snow was very hard going. We reached the proposed site after eight hours—later, we did this walk regularly in two and a half hours carrying big loads.

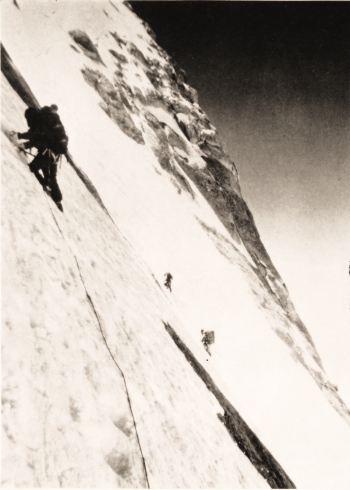

After three days of humping loads to advance base, Chris and Nick attacked the spur whilst the rest of us continued to ferry loads. They climbed 600 ft. which they fixed, and then returned to camp. Two days later Chris and I pushed further up in search of a site for camp 1. There was only one possible safe place, a niche in the ridge under a vertical wall. As our route at this point was on the left flank avoiding the steep crest, it meant a 200 ft. detour to reach the camp, and so obviously a 200 ft. abseil every morning before climbing could commence. However it had to be, there was nothing but 50° / 70° ice and rock until the South West Col.

Chris and Nick, Mo and I climbed, jumared and abseiled for seven days until eventually Mo and I reached the Col on 25th June. The past week had been trying but gratifying. Awake at 1 a.m., shivering until the first brew goes down. Trying to force down unpalatable, plastic that expeditions have to live on and eventually donning all the paraphernalia. First descending then ascending the ropes to the previous day’s high point, then at last starting to do some proper climbing until about 9 a.m.—then dropping the gear and fleeing—trying to reach camp 1 before noon. The express trains are roaring down the line by then, the grand pianos are being hurled from the summit and “God am I thirsty.”

At the outset of this trip, Doug and Tut had decided they wanted to try the South rock pillar of the peak, alpine style. It was away to our right and soared vertically for 2,500 ft. A gigantic icefield above led eventually to the summit rocks.

Occasionally we four would catch glimpses of two small figures climbing the steep couloir to the foot of the wall, or trudging up and down the glacier. One afternoon we saw them descending, very very slowly. Something was wrong, no matter how tired, these two guys move faster than that.

On the 26th June Chris and Nick left camp 1 with five days’ food. They were hoping to make an alpine style push for the summit. Having pushed to the col the previous day, Mo and I were tired. We decided to go down for a rest and see how our two friends were. Advanced base was deserted, which was very odd indeed. Doug and Tut weren’t on the hill but why should they go down to base when all the food and equipment for their climb was now up here? We had no choice but to go down and find out.

We ran down the moraine into base camp. Doug and Tut were there along with Pat Fearnehough and Tony Riley of the Latok team. They told us the sad news that Don Morrison, their leader, had fallen into a crevasse and disappeared. The three Yorkshire men had been ferrying supplies up to camp 1. Paul Nunn and Pat Green were still pushing out the route around 20,000 ft. unaware of the accident. They descended three days later when they ran out of food and rope and realised something was amiss.

Our assumption that something had happened to Doug and Tut in the couloir was proved correct. Tut had been abseiling, when a large boulder came down and crushed his leg against the wall. He and Doug were resting at advanced base when our camp cook brought up the message about Don. Obviously they descended straight away to offer any assistance that might be needed. Tut’s leg was now very swollen and bruised, he could hardly walk. This was, in fact, the end of the climbing for him—it never got any better. It was only after the trip, when he returned home, that he discovered he had a blood clot.

Doug, Mo and I now joined ranks. I proposed that, instead of heading for the summit “the easy way” that Chris and Nick were attempting, we should climb direct from the South West Col to the South West shoulder, straight up the pillar to the West Summit and then traverse to the main summit—this was accepted. Three days later we were at the Col. We dumped our loads and abseiled back to camp 1. The following day we dismantled the camp and prussiked back to the col. “I’m sick of the sight of these ropes,” Mo said. “Thank goodness that’s the last time we’ll be climbing ’em.” I, the pessimist added, “Don’t bet on it mate.” Two days later, back in advanced base, I reminded him of his words. His reply was a terse imperative.

Chris and Nick were three days overdue on their climb. Meanwhile we three had pushed from the col to the South West shoulder and made a tent platform and dump there. However we were worried about our two friends and decided to abandon our attempt to search for them, starting the next morning. Whilst still snug in our pits, there was a knock at the tent door—enter Bonington and Estcourt. “Well did you get up it?” says Scott. “No” says Bonington. “Good” says I. Mo laughs.

They had in fact made a fine effort. They’d been climbing for a week and had got to the foot of the 700 ft. summit tower. Then they decided they hadn’t enough gear or woomph to tackle it, so traversing left they had ascended the easier South West Summit.

Chris and Nick were still keen to have a try for the main summit via ‘our’ route. From what they had seen, it was obvious that we neither had enough food nor gear with us at the col, so once again we all descended to base camp. Nick decided eventually that he was still too tired to attempt the summit again but he would help carry gear back to the col. Tut also agreed to do the same, his leg was feeling a little better.

Mo, Doug and I set off once more for the three day climb to the col. The others were to follow two days later, when they should have been fully rested. Four days out, we three reached our previous high point, the South West Shoulder at 22,000 ft. The following day we started work on the steep 1,000 ft. pillar above. The climbing was very steep and strenuous, mainly chimneys and cracks full of ice. After three days’ work, Mo and I eventually reached the top of the pillar and climbed a 500 ft. ice gully which led to easier ground. Elated, we set off down the ropes to the shoulder.

The day after, the three of us were festering in the camp, watching a weary solitary figure prussicking up towards us. It was Chris; Tut and Nick hadn’t been fit enough after all, to make the carry. Chris had carried as much food as he could manage. However that, plus food in camp, only came to four days’ supply. With a bit of luck we estimated we could just about do it, three days up and one down—optimists.

Next morning we were off. It was 11th July and not a cloud to be seen, sacs not too heavy yet. We left the tents behind, intent on snow-holing. Moving quite swiftly up the fixed ropes on the pillar picking up gear which we’d cached on the way, we reached our previous high point by mid-morning. At 5 p.m. after climbing easy, yet exhausting snow, we were under the South West Summit and dug our first cave.

No need for alarm clocks here—no doubt even brass monkeys would suffer. Mo and I led off across steep, hard water ice, after the traverse, directly upwards to the ridge, 500 ft. below the South West peak. Time for a brew and a smoke before Doug and Chris took over to climb the steep broken rocks to the summit. This summit is around 23,600, a personal height record, it felt good. No time to linger though, we had to descend the ridge, traverse the snow field and hope to find the cave that Chris and Nick had dug two weeks earlier. We found and enlarged the cave, cooked, then slept.

“Do you know what today is?” said Mo. “Pay day?” I asked sarcastically. “It’s the 13th” and—”You don’t believe in that do you” cutting him off in his prime. “No, but I usually don’t move from the fire and telly on a 13th!”

We were traversing the slope to the foot of the final tower. Doug and Chris were an hour or so in front. We were deliberately so far behind, for Mo, who was making a film for the Beeb, wanted some film of them on the final tower.

At four in the afternoon, Doug was pegging up a vertical wall 200 ft. below the summit. A hundred feet lower down Mo and I realised that, even if Doug and Chris reached the top, no way would there be enough time for us to get there in daylight. Sadly we started to descend but determined to have a go the next day.

Eight p.m., I was lying in my sleeping bag, it was nearly dark now. An hour earlier Mo and I had seen Doug and Chris reach the summit. “I’ll just go out for a final call and see how they’re doing,” Mo announced. He was standing in the cave entrance, then “Oh God no—he’s gone” he screamed. “What, who’s gone?” I yelled but I didn’t want to know, I feared the worst. Joining Mo in the entrance I could just pick out two figures in the gloom. Fortunately “he hadn’t gone.” It was Doug—in descending he had traversed about 130 ft. when he slipped on ice. He penduled at great knots and smashed into a gully wall. In the fading light Mo hadn’t seen the rope, hence his immediate reaction. We could hear them talking very clearly now. Doug, quite correctly as it turned out, diagnosed two broken legs. Mo and I returned to the cave, our friends dug out a ledge where they were, it was dark now.

The morning of the 14th was clear as usual. At 6 a.m. Mo and I were off across the snow field laden with ropes to fix a hand rail for Doug. Having spent the night without down or tentage, they were frost-bitten and tired.

It took us six hours to get back to the cave. Mo out in front fixing lines and hacking buckets across 60° slope for Doug to crawl in. Me behind clearing the ropes and retrieving the pegs. The peg situation was critical, when Doug took his fall he turned upside down. The bandolier carrying nearly all our gear was lost. We now had only four rock pegs, two ice pegs and eight karabiners and 1,200 ft. of abseiling before we reached the fixed ropes.

It was an odd sight inside the cave. Mo’s feet up my jumper, Chris’s feet up Doug’s jumper and me massaging Doug’s feet. And all the while brews and yet more brews were consumed. We had one meal left and decided to eat half now and the other half the following evening, when we should be well on our way back to the South West Shoulder. “What time is it?” Mo asked, shaking me awake. It was pitch black and I could not be bothered. “Christ, I can’t breathe. Put on the torch” he demanded. I was fully awake by now, I couldn’t breathe either. No wonder, the cave entrance was blocked solid with snow. We cleared it away and to our amazement and utter dismay, there was a raging storm blowing. Our curses awoke our friends and after a confab., we decided we should try to descend.

Of course, the Ogre being what it is, in order to descend, we first had to ascend the 500 ft. 60° slope to the South West Summit. I volunteered to try and break a trail. Stepping out of the cave I was hit by a horrendous wind, with spindrift making it virtually impossible to see. Within minutes my goggles were iced over. I removed them but my eyelashes iced and welded my eyes together. I tried to keep moving upwards but in this raging storm and chest-deep snow I was losing and knew it. I returned to the lads. One hour I’d been gone and only achieved eighty miserable feet.

The rest of the day was spent playing cards. Every 45 minutes or so we had to unblock the entrance as the storm raged on. That evening we ate the last of our food, instant potato and soup mixed. All we had left now was tea bags and curry flavoured stock cubes (revolting).

When I ventured out early on the 16th, the weather had slightly improved. The wind was still blasting but it wasn’t snowing, though the continuous spindrift was troublesome. Leading on a 300 ft. rope I reached a rock buttress after a two hour struggle. The rope was anchored and Mo jumared up. I led off again as Doug set off from the cave. During my frequent rests, I’d watch Doug jumaring on his knees.

At last the South West Summit—it had taken me four hours to reach it. It would be another four before Chris at the back arrived there. From now on it was all down hill. Mo went first rigging the abseils, chopping off the ends of the ropes for spike and chock belays, rather than leaving the precious rock pegs.

At around 6 p.m. we found our snow cave of the 11th but it was virtually full of snow and had to be re-dug. The weather had steadily worsened all afternoon and the cold was soon unbearable. None of us could wait any longer and we abandoned the digging and piled in. The roof was far too low and the stove’s heat melted it. Mo and I, under the lowest part, had our sleeping bags soaked.

In an effort to keep out the driving snow, I piled all the rucsacs and any excess gear up to the entrance. We awoke the following day under a foot of snow and half the gear buried. Mo lost a crampon which we never found. Doug crawled on. At mid-day we reached the gully at the top of the South West Pillar. Only 200 ft. below was the start of the fixed ropes, which went all the way to our tents on the shoulder. I drove in the last peg and fed the double rope down the gully. Mo, Doug, then I abseiled. Nearing the bottom of the ropes, I noticed neither end was tied off to anything. One however was twenty feet or so longer than the other and reached the first fixed rope. I penduled across to.a spike on the left and tied the long rope off, then continued down to the fixed rope. I waited for Chris to warn him about the short rope. In the driving snow he didn’t notice it and my shouts were lost in the wind. He shot off the end, bouncing twenty feet until he was pulled up by the one I had tied on the spike. This act definitely saved his life. As I told him later”, it was just an impulse, I could easily have left it and scrambled down to the fixed rope below but I decided “No, just in case Chris doesn’t see it.”

Later that day when we were all re-united in the shoulder camp, we learned of Doug’s incredible escape at the same place. Abseiling down the ice on his side, he flew off the ends of the ropes. The first fixed rope was in fact a horizontal one and Doug just happened to flop over it! (He never waited to warn me though).

The 18th July dawned worse than ever, the tents were virtually collapsed with the amount of snow that fell in the night. I ventured out with a shovel to clear it. This little episode cost me frost bite in the fingers. Chris’s voice had virtually disappeared overnight and he started croaking at me from the other tent (occasionally coughing up bubbles). He wanted to set off down. “We’ll die if we don’t.” “We’ll die if we try,” I told him. “I’m going back to bed to suck an oxo and smoke a tea bag!” and I did.

The 19th, our fourth day without food; strange how one’s body gets used to it after a while. Not like tobacco, I could murder a fag. Cloudy but not snowing, we packed the tents and headed down to the col. Mid-day found us at our old camp site digging for a bag of food we’d left there. After two hours all we had found was a bag of rubbish—exhausted we gave in. By now the clouds had disappeared, the sun was blazing down, the storm was done. We pushed on, it was half a mile across the col to the top of the 3,000 ft. ridge. Wallowing in deep wet snow it took us four hours. There we camped. Doug was still strong despite his legs. Chris on the other hand was getting weaker. His left hand had swollen, he had pains in his chest and he was coughing more bubbles than ever; in fact he had pneumonia, brought on by two broken ribs which he got during his fall. In addition, his hand was broken in two places.

We left early the next day, hoping to make advanced base. Mo went first to check the ropes and anchors and to assist Chris. Doug and I followed an hour behind. As we got lower down the ridge I kept looking for the advanced base tents far below. I couldn’t spot them and I was convinced the storm had carried them away. I then saw Mo and Chris arrive at the area of the camp, they lingered around a few minutes, then continued down the glacier. Doug and I arrived at the site some four hours later; there was absolutely nothing to be found. Roping down the ridge, Doug had been nearly as fast as the rest of us, but now, on the relatively flat glacier, having to crawl on all fours, he was painfully (literally) slow. Occasionally there was a steep section where I could run down with the rope pulling him along on his backside. Generally though I couldn’t help and it was his own strength and determination that kept him going.

Around midnight Doug crawled and I staggered into the meadow. It had been a long day, in fact it had been a long week, six days of it without food. Base camp wasn’t there any more. Just a pile of nougat bars and a note giving us up for dead. It was to be two weeks before we got back out of the hills, but that’s another story.