Colola An Ascent In The Apolobamba

by M. Smith

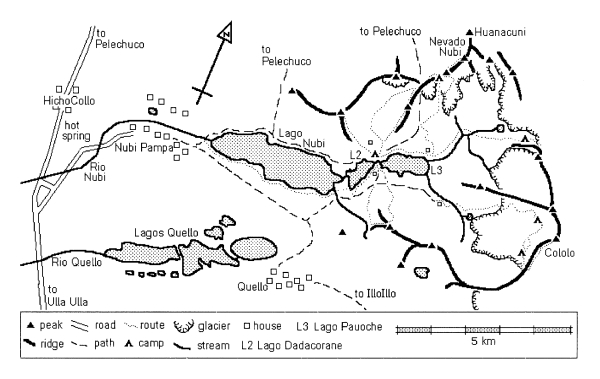

An account of the ascent of a new route on Cololo, also called Ccachuca. The climb was part of the 1988 YRC expedition to Bolivia.

Morale was not at a high point, as the sun set on the first day of August. The entire day had been spent cooped up in a truck. We were hot, dry and dusty and had been bounced about to the point of numbness. Any discussions with the “maestro”, as the driver called himself, had reached the point of stony silence. We had repeatedly requested that he turn right along one of two vague tracks across the pampa. He was sticking to his employer’s map. An old envelope bearing two words and four squiggly lines was all the information available for a 270 km route which he had not travelled before. We finally arrived at a place we had not wished to visit.

The morale of the expedition was at an all-time low. One member was recovering from dental surgery and another suffering from altitude-induced headache. A puncture and muddy splashing from driving through part of Lake Titicaca were additional elements which made for a depressing day.

In the adobe (mud-brick) village of Hichocolo the local schoolmaster proved to be our salvation. Despite an ailment which confined him to bed, he was, between bouts of coughing, able to confirm that one of the tracks we had passed was the one we wanted. A little later and with his assistant as guide, we were able to tolerate an hour’s roller-coaster drive in total darkness to Nubipampa village.

Our arrival was received by the villagers with many handshakes and greetings. We were given accommodation in the schoolhouse. The truck was unloaded and sent back to La Paz. Later, after drinking tea and eating cold chicken, we tried to sleep on the hard floor, but it was not easy. Inquisitive faces peered in through the windows. A drum trio performed close by and the candle-lit picture of Simon Bolivar (obligatory in every classroom) peered down on us. But we had at last arrived and our confidence was returning.

Before breakfast I stepped outside to make sure that we had arrived at our intended destination. The sight I beheld was enough to restore the enthusiasm of any mou ntaineer. Across a deep blue lake, like a scene from a child’s story-book, stood a real mountain; sharply pointed, snow-capped, with steep rock sides set against a cloudless blue sky. Cololo, our objective.

A week later the view was not so rose-tinted. We had established a base camp at 15,000 feet by the side of a lake and made our first attempt on Cololo. It had failed. The assault party consisting of David Hick, Ian Crowther and myself had camped on the glacier at 17,500 feet, having had assistance from David Martindale and John Sterland. Next day we threaded through the seracs of the upper ice-fall and ascended a rock ramp to reach the west ridge at 18,700 feet before being beaten by lack of time and energy. Despite the set-back we were pleased with our progress and optimistic of the outcome. After a day’s rest at base camp we were ready to make a second attempt.

Our departure breakfast was just the thing for stoking up energy before a climb. Three bowls of porridge, salami, local cheese, biscuits and week-old bread washed down by tea was good fare by any standard, if one had the stomach. Our cook, Francisco, had added to his culinary repertoire by making tea to an acceptable standard, thanks to lan’s thrice-daily tutelage. Despite such luxury we were anxious to be away. Our brief rest had been worthwhile.

Carrying our sleeping-bags, duvet jackets and more food than on the first attempt, Ian, David, Harvey Lomas and I setoff towards Cololo. Our intention was to ascend the glacier to the base of the north ridge and have a look at it. If it looked doubtful we planned to traverse the glacier and attempt the west ridge again. Harvey and Ian would retrieve one of the tents and gear left at the high camp and return to base camp.

The slow, steady pace tempted frequent stops to admire our surroundings. Some way above the camp we came across an area of flat pasture land and a primitive building built of boulders, adobe and topped by a grass thatch. A herder’s dwelling. It was protected by ferocious dogs which snarled and barked at our presence. A score of llamas peered imperiously over the stone wall of their dunging ground and wondered what all the fuss was about. We sat down for a rest at the side of the pasture in the lee of a stone wind-break. At our feet we saw a miniature copy of the dwelling we had passed. Pebbles for walls, twigs for timber and thatched with grass. Several hours of painstaking work. A child’s toy or offering to some unknown power, perhaps?

We climbed up the spine of a lateral moraine which rose from the pasture. Cattlegrazed by a partly frozen stream and we could hear the thin, plaintive cries of the vicuna as they galloped lightly away. A slender, more graceful relative of the llama, they are common to this part of the Ulla Ulla national reserve and a protected species. The strangest site was the viscacha, a rodent aboutthesizeof a dog, shaped like a squirrel but with rabbit’s ears, a cat’s tail and the gait of a kangaroo. The weird animals bou nded up the screes into the distance as we passed.

On reaching the top of the moraine we cached our lightweight boots and donned plastic double-boots before stepping on to the glacier. The way was straightforward, winding upwards past crevasses towards a rock buttress, a spur off the lower reaches of the north ridge. Our only problem was keeping a footing on the glacier’s surface. It was rough and covered with angled teeth which faced the sun. Varying up to three feet in length, they sometimes broke under our weight and made it impossible to set an even pace. Eventually they gave way to steepening powder snow, up which we floundered until arriving at our old camp on a broad shelf parallel with the north ridge. The tents were still standing.

Whilst Harvey and Ian packed one tent and its contents and set off back to base camp, David and I packed the other tent. The camp needed to be repositioned higher and further across the glacier to give a better start to the second attempt. With loads of 30 pounds we traversed the glacier shelf and entered the upper ice-fall by way of a partly collapsed snow-bridge guarded by seracs. Having covered the route before, we were roped up, confident and moved faster. As we climbed higher towards the head of the glacier, we reached the point of decision. The north ridge with its generally easier angle and two rock buttresses was rejected. On the principle of “better the devil you know” we traversed the head of the glacier towards the west ridge.

We moved up through a steeper section containing a few crevasses and arrived at a small plateau on the glacier, below the rock ramp which leads to the west ridge. This provided us with a campsite at 18,000 feet, just a few metres from where the seracs plunged over an edge to the lower part of the glacier. As the glacier swung up and southwards, we had ascended the gentler slope on the outer side of the curve, the inner side being a chaotic jumble of large ice blocks. The campsite gave a magnificent view of the Northern part of the Apolobamba. To the left were Ananea and Calijon, two distinctly separate mountains in Peru. In front of us, behind the almost horizontal ridge of Huanacuni, was the Palomani chain which forms the Bolivia-Peru border. Over to the right at the end of a mass of other peaks were the snow-domes of Chupi Oreo and Salluyo, the highest peaks in the range. Further to the right at the other side of the North ridge was cloud, marking the edge of the range and its descent into jungle, a continuous descent of 3,600 kilometres to the Atlantic Ocean. As the view faded, we were treated to our first sunset in these mountains.

Unusually that night a wind blew steadily and, although the temperature was not low at – 7°C, it felt cold. Having enjoyed a sunny evening’s view to the west, we paid for it next morning by being in the shade. We brewed up, whilst staying warm in our sleeping-bags. After a quick donning of outer layers we trudged off up the scree-covered rock ledges of the ramp towards the ridge. To banish the cold we tried to keep a good pace and restore circulation to numbed feet and fingers. A stop to attend to the needs of nature and the process had to be repeated. We were travelling light and soon reached the ice-covered ridge, where we clipped on our crampons.

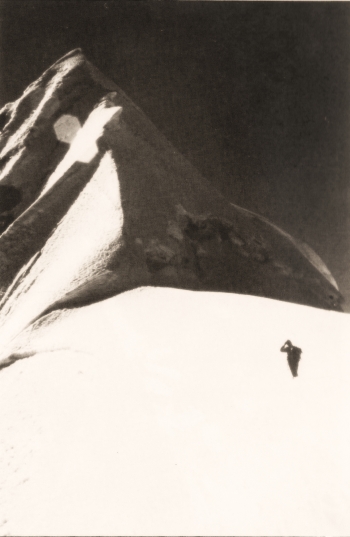

The first section of the ridge consisted of steepenings topped by cornices. These were climbed with only occasional need for protection. Ahead lay the enormous fang of ice, or so it appeared from below. The left side was a steep face of ice descending directly to the head of the glacier at an angle of 70 degrees. On the right it overhung by a similar angle. Directly in front was its vertical edge, separated from us by a wide, impassable crevasse. This time we were fitter, fresher and more confident of the way ahead. A small descent to the left bypassed the wide part of the crevasse and led on to the face. The surface was like a choppy sea, frozen and up-ended. The sides of the “waves” formed near-horizontal gangways, whilst the wave above allowed convenient placements for ice-screws and wart-hogs. Cutting off the frozen “crests”, which threatened to push one “overboard”, and stepping up now and again to the next wave were the only technique needed. We finally arrived at a small col on the far side of the face.

The time was 11 o’clock and we had been on the move for three hours. Over some chocolate and an orange we studied the final slopes. The ridge rose at an average angle of 50 degrees. Towards the summit it was narrower and steep on both sides; generally icy on the left, rotten or powdery on the right. It was slightly concave and made up of several 100-metre sections. Each section was divided from the next by small, stepped crevasses about five feet in height. As we traversed, we repeatedly had to make awkward moves to overcome the crevasses and the start of a section. Taking each one steadily and leading through, we were unaware that our every move was being watched through binoculars by Harvey at base camp. The moves tended to come in spurts of ten or more, interspersed by a couple of minutes of recovery time.

Near the summit David was belayed some distance below a step. I moved up to him and over the step on to a 15m section of very hard ice. It was at an angle of 70 degrees and felt considerably steeper than any previous section. David climbed up to the step to improve the belay and gave me sufficient rope to move past the difficulty and belay a matter of feet below the summit. At one o’clock he joined me at the belay and we walked the last few steps to stand on the summit of Colojo. A sense of self-preservation prevented us from standing on the very tip of the cornice, which overhung the South face, but it was a real summit, the meeting-point of three narrow ridges.

At 19408 feet, Cololo is the highest of the Apolobamba peaks entirely in Bolivia and the most beautiful. It had attracted three previous ascents; a German party in 1957, a Japanese party in 1965 and an American party in 1986; all from the South side of the mountain. We were delighted to have achieved the first objective of our expedition.

The views from the summit were good. Snow-clad peaks lay to the north and south, the altiplano stretched westwards into the distant haze, whilst to the e’ast there was nothing but cloud. Our descent by the same route was uneventful but tiring. We struck camp by five o’clock and recrossed the glacier, as the shadows lengthened and the temperature fell. By the time we reached base camp it had been dark for an hour and we relied on a light from the camp to find our way back.

Later in the expedition we went on to climb Nevado Nubi and lllimani in the Cordillera Real but the ascent of Cololo was in many ways the highlight of our visit to Bolivia.