Meet Report: 17 August – 6 September 2017.

This article is an overview of what we did. For details of the logistics and planning please refer to the full article in the overseas meets section of the archive. You can also watch a video created specially for this meet which will open on the YRC facebook page.

We had heard about the many attractions of the Wind River Mountains; fabulous scenery, wild and rugged terrain for backpacking and spectacular granite spires for climbing. With a solar eclipse thrown in as well, this was the chance for the trip of a lifetime. Five members signed up and in 2016 began planning for a three week trip to coincide with the total eclipse in August 2017.

By the early months of 2017 a plan had emerged: fly into Denver; acclimatise for a few days with short hikes; watch the eclipse from Riverton; backpack near the Cirque or climb there with a horse and wrangler taking in their climbing gear; move round to Pinedale to the west of the range and backpack in to Titcomb Basin below Fremont Peak; then if there was time stop off at Rocky Mountain National Park for a day on the way back home.

The outcome was a successful trip with a variety of contrasting experiences for both backpackers and climbers. Good weather helped to ensure a memorable experience for all.

Hikes on the way in

We flew into Denver, the “mile high city”. Having a few days to spare before the eclipse we took our time, acclimatising to the conditions and having some relaxed hikes on the way.

The first, in Lory State Park, about 1 ½ hours from Denver took us to just under 7000ft on a seven mile circuit of forest and moorland trails, taking in the viewpoint of Arthur’s Rock, overlooking Horseshoe Reservoir.

Next day we turned off the road at Agate Flats towards the impressive steep granite of Lankin Dome. After crossing the wagon wheel ruts of the Oregon Trail we soon parked up, having struggled with soft fine sand. Expecting a complicated selection of gear levers and ratios to engage 4WD, we entirely missed the little switch that converted our SUV into an off road beast. A flat walk of a few miles past a stock pond, antelope hunters’ large calibre rifle cartridge cases, a snake and a horned lizard among a lot of sage brush brought us to the foot of a 7,617 ft peak about 3km west of Lankin Dome. Each selecting different routes on the northern side we made our ways to the summit. Some scrambling was required before a gully was reached. Along the way Tim pulled on a handhold which broke off. It fell from his hand and struck his shin leaving a 6cm long gash. We covered it with a strip of sticking plaster and continued. The summit was approached from the east and we left it towards the west to take the NNW ridge down – parched and scratched. This was a 4½ hour outing. Tim’s shin was cleaned, stapled and dressed later that day at the hospital in Lander. While he drove across town to the hospital the other three of us showered, changed and were heading for the Lander Brewing Company’s Cowfish restaurant when he pulled up beside us having been treated. Expecting crowds for the eclipse, the hospital had brought in staff from the surrounding areas and they were sat around, feet up on the table, waiting for custom. They were delighted to see him and he was insurance checked and being treated in ten minutes. Twelve staples were needed to hold him together. The bill for 20 minutes in casualty totalled $4,175.

On the eve of the eclipse there was some provisioning to be done so the hiking was curtailed. We drove 9½ miles from downtown Lander along Sinks Canyon to park at Bruce’s Bridge. The 700 ft rise along the Popo Agie River to the upper falls is spread over a clear almost two-mile long trail. We turned back soon after that at 8,500 ft to give a 2½ hour round trip. The challenge at the falls is to slide down a steep water-polished rock to be launched into the air and plummet the last few metres into the plunge pool. It is a local rite of passage. We gave it a miss. Having made an early start, we saw few people on this popular trail on the outward leg but returning we were soon meeting families with dogs and grandchildren then rangers trying to sort out impending parking chaos.

Eclipse

Our location in a spot north of Riverton was chosen to be close to the centre line of totality (12km where the path width was 107km) to give 2 minutes and 20s of totality. We could not find accommodation closer to the centre line in this area under £2,000 even nine months ahead. Camping in the Winds was considered but this would have considerably reduced the chances of a clear sky. We paid £1,000 to sleep two nights in someone’s ranch home while they slept nearby in their RV. The previous night cost over £150 per person in a dilapidated twin motel room without breakfast. Thankfully the brewery restaurant did not appear to have increased its charges.

Haze and some cloud gave some concern as the day of the eclipse dawned. But as the sun rose the skies cleared. This was the case for almost all the US except for close to the east coast where heavy cloud persisted. From first contact (the moon starting to pass in front of the sun) around 10:20 we were observing with dark glasses and experimenting with camera settings and using binoculars to cast an image onto a screen.

Little changed down on Earth until totality was around 20 minutes away. By then things were distinctly dimmer, getting cooler as the mozzies emerged to make a nuisance of themselves. Birds flocked, went to roost and quietened down. Colours muted as the remaining light slipped from yellow to grey. All around the horizon (we were on a large plain) were sunset colours: oranges and browns. We shivered as the temperature fell dramatically. Finally, around 11:40, totality arrived and we could hear distant whooping and cheers in the darkness. Dark glasses were quickly whipped off and photos taken without filters. The sun’s coronal glow around the sides of the moon was visible and our photos picked up solar flares.

With only a short time to take it all in we were all too soon treated to the diamond ring of the first intense sparkle of sunlight peeking round the moon. Then gradually the light and temperature returned to normal and it was off to the supermarket for some supplies and Arby’s for a beef sandwich.

Backpacking from Dickinson Park

The backpacking group, David and Alan, watched the climbing trio, Michael, Richard and Tim, start their long walk-in to The Cirque, then had a second brew-up and a second breakfast, before following them across the marshy trail south of Dickinson Park trailhead.

We then followed the Smith Lake Trail westwards, initially in fairly dense forest, before rounding the prominent Dishpan Butte, and continuing westwards on a rough trail towards Smith Lake. We’d read that this area has a resident population of black bears, so when we occasionally met other backpackers, we enquired about sightings, and though most were negative, two backpackers reported seeing a female bear with young in a meadow near Smith Lake.

We continued on past Smith Lake, which was seen through trees to the south of the trail – relieved but also a little disappointed not to see bears – and found a good wild camp site on the north shore of Middle Lake. Cathedral Peak, to the west, and its two huge east ridges, provided a fine mountain setting. Later in the afternoon, without heavy backpacks, we tried to go further westwards towards Cathedral Lake, but the valley was blocked with fallen trees and rocks, so we retreated to camp, where David tried his hand at fishing in Smith Lake, though unfortunately fish didn’t take the bait.

Next day we backtracked about two miles to join the High Meadow Trail southwards, where we encountered an unexpectedly wide and turbulent crossing of a tributary of Smith Lake Creek. The rough, undulating trail continued to a series of waterfalls on High Meadow Creek, and a steep descent to join the North Fork Trail, immediately before a second knee deep river crossing. We were then on the route of the climbing trio the previous day, with a third, more turbulent river crossing an hour later. Eventually we reached the planned camping site at Lizard Head Meadows, a fine spot, despite mosquitoes, with superb views of Mitchell Peak, Dogtooth Mountain, The Monolith, and tantalising views further westwards into The Cirque.

We occasionally met small groups of other backpackers, who’d gone into the wilderness specifically to view the eclipse from a mountain setting; they were all duly impressed, though they’d been lucky to have cloud-free views. We chatted for some time with one lone walker, a man who knew these mountains in detail, and he described much of the geology and rock scenery we were to see over the next few days. He subsequently encountered our climbing trio.

Next day, after packing and hiding much of the gear, we continued westwards to Lonesome Lake. What a fine setting this is, fully justifying the descriptions we’d read in advance of the visit. Enclosed on three sides by shapely granite peaks, we got out the stoves, brewed tea, and sat for a while, trying to absorb it all. Quite suddenly, about thirty yards away, a large moose, with a fine set of antlers, ran at high speed across our path, to disappear into scrub and forest north of the lake.

We retraced our route to Lizard Head Meadows, collected the gear, and ascended the Lizard Head Trail for about a mile, to an un-named lake east of Bear Lake. As its name suggests, this is allegedly frequented by bears, and though we didn’t see any, they probably saw us first. This was another fine camping spot – David fished the lake, unfortunately without success, and Alan went up to Bear Lake, in a rock-strewn cirque, totally dominated by Lizard Head Peak, 2,000 feet above.

Next day we resumed our route on the Lizard Head Trail, which here goes over a huge boulder strewn plateau, mainly at an altitude just short of 12,000 feet, devoid of any form of shelter, and thus a place to beware of in storms. Huge compensation, though, in the fine array of granite peaks to the west, stretching northwards as far as the eye could see – Lizard Head Peak and Camel’s Hump, separated by a high cirque and small glacier, the oddly named August 16th Peak, and increasingly a series of lakes up to Grave Lake, as well as umpteen other peaks stretching to the horizon, too far away to identify.

The Lizard Head Trail goes high on the eastern flanks of Cathedral Peak and two un-named peaks, all over 12,000 feet high, and from this angle resembling huge tors, composed of pillow lava.

Now on the northern slopes of Cathedral Peak, we followed the trail north-eastwards, descended a 200m long snow slope, joined the Bears Ears Trail, then turned west and descended to Little Valentine Lake for our next wild camp.

This was yet another good mountain wild camp site, a short distance above the lake, well sheltered from wind, with a pair of marmots resident among rocks across the stream.

The final day of this mini-backpacking outing involved ascending the part of the Bears Ears Trail we’d descended the previous day, then zig-zagging round and to the north of Mount Chauvenet, walking amongst outcrops of pillow lava at an altitude of 11900 feet. There was still a grandstand view of mountains in the northern part of the Wind Rivers Range, so grand it was difficult to look elsewhere.

The trail turned eastwards, beneath and north of the Bears Ears Mountain, where we had close-up views of a number of the “bear’s ears” – rock formations which justify their name. We crossed a large snow slope, then Sand Creek, had a brew of tea, and were passed by a group of five men on horseback, who’d come from Valentine Lake – the larger lake below our previous night’s camp.

We crossed Adam’s Pass and followed the trail north-eastwards through woodland above Ranger Creek to Dickinson Park Work Center, then south along the access road to the campsite at Dickinson Park.

We’d completed our five-day backpacking on schedule, and had a spare day before the three climbers were due to return from The Cirque. We therefore drove north to Moccasin Lake and walked to Mary’s Lake on an unmaintained, deteriorating trail; the trail then totally disappeared, so we bushwhacked north to Shoe Lake, eastwards to Little Moccasin Lake and eventually made our way to the northern end of Moccasin Lake, where to our relief we found a fisherman’s trail along the east shore, enabling us to get back to the vehicle. On this day we saw recent bear scratches on tree trunks and bear droppings, and though we didn’t see a bear, in the wildest part of this maze of fallen trees and vegetation we disturbed an elk, which made off at speed.

After a second night at the Dickinson Park campsite we walked for two hours along the North Fork Trail, in the hope that we might meet our climbing colleagues, but it was not to be, so we returned to the campsite to await them.

Climbing and scrambling

The hike into Lonesome Lake and up into the Cirque of the Towers required a 4am start from Riverton and took a full day from the Dickinson Park Trailhead. The North Fork Trail was reached by crossing the marshy bottom of the valley east then following a slight ridge before a steep descent south had to be made to the North Popo Agie River.

This was followed upstream south then west for several miles with four knee-deep river crossings to reach Lizard Head Meadows where trekking llamas were grazing. The trail became distinct again on the far side of this marshy ground and continued west on the north side of the river to Lonesome Lake. While waiting here for the horses to bring our gear, two of us prospected up into the Cirque for a suitable campsite. Aware of the lateness of the day and the tired state of the party an adequate compromise site was identified. In the event, having brought up much of the gear to that point, it was used to prepare a meal which allowed us to continue to a higher bench with a better water supply. That site, a little east of and below the prominent waterfall, proved to be a good spot throughout our visit.

After our exertions of the previous day’s walk in to camp by the Cirque of the Towers we decided to explore the lower levels of the Cirque and check out the approaches to our selected climbs. Although the area is a long way from the nearest trailhead, all the towers are within an hour and a half or so of the campsites above Lonesome Lake. That lake was sadly one of the first to become polluted due to human activity but efforts at education by the Ranger authorities and a ban on camping within ¼ mile of the lake have greatly improved the situation. People seem to be taking the problem seriously here and elsewhere in the range, making low impact camping a priority. The basin below the Cirque of the Towers, with its chaos of boulders hiding little meadows and copses of pines holds a multitude of secluded campsites, far enough from streams for hygiene but close enough for a convenient water supply. Although there were many other backpackers and climbers camping, the sites were so well hidden we never felt crowded.

We set off to reconnoitre Pingora Peak and Wolf’s Head, both sharing the same initial approach through an area of massive boulders. Luckily a climbers’ path has formed and the going was surprisingly easy to a small cairn marking the zigzag route up ramps and ledges onto the south shoulder of Pingora. Here we could trace our planned route for the morrow before descending the ledges and working up to the foot of the wall leading up to Wolf’s Head. We had already been warned about the horrors of the direct approach up 300ft of steep ledges and a pair of descending climbers agreed declaring it ‘very scary’. We climbed a short way up a blocky gully which looked fine and decided on that way for later.

The South Buttress of Pingora was our first route the next day, a four-pitch climb rated at 5.6 (UK severe). We had youth on our side and it seemed a waste not to use it so we pointed him up the climb and off he went. Enjoyable exposed climbing up corner cracks on impeccable granite led all too soon to a 200ft scramble on to the blocky summit. One pitch was rather harder (5.7, UK HS/VS), so we may have been off route. Pingora dominates the view from below but on the top one feels dwarfed by the much higher peaks around the Cirque. Three airy abseils reunited us with our approach shoes and a leisurely stroll back to camp after a short but satisfying day.

The second route, two days later was the famed East Ridge of Wolf’s Head, 5.6. Although the climbing is not hard this is a much more serious proposition being virtually inescapable and with a long approach and descent. Given the reputation of the Cirque for afternoon thunderstorms, an early start is essential. We did but even so there were several parties ahead who must have set off in the dark.

Having decided on the indirect approach we scrambled up a mini bergschrund beside a snowfield to the base of our gully. This went easily apart from a short excursion onto the flanking slabs where we used a rope although it turned out not to be really necessary. Topping out on the ridge we then had to cross Tiger Tower by one pitch of Diff climbing and an abseil down the other side to the Wolf’s Head col. From here the aspect is somewhat alarming. The ridge is spectacularly narrow and foreshortening makes it look impossibly steep. Once you get started though the true angle becomes clear and delightful V Diff climbing on granite with the friction properties of velcro took us in about 350ft to the more level section of the ridge. The exposure along most of the routes is “awesome” (you can’t climb in the USA without using that adjective), a couple of sections of admittedly easy climbing were exceptionally narrow.

We soon reached the four pitches of technical climbing; tenuous toe traverses, hand traverses and squeezes through holes from one side of the ridge to the other. All delightful climbing on beautiful rock with stunning situations. Route finding was easy. If you can climb it, you’re going the right way. If you can’t you’re not. Eventually some easy scrambling reached the airy summit with room for two. The first abseil station was just below the summit and four abseils of 80-100ft reached a ledge and terrace system which took us the ¼ mile to the col before Overhanging Tower and a final abseil. All abseils can be done on one 60m rope. We thought it was all over but the descent from the col on very steep gravel was horrible.

However, all things come to an end and we soon reached easier going and a delightful walk out surrounded by peaks turning golden in the setting sun.

Pingora was a good climb. Wolf’s Head was an outstanding climb. If one is climbing in the Hard VS to low Extreme grades there is a lifetime of magnificent climbing to go at here. I wish I had discovered it years ago!

Besides the rock climbing in the Cirque some of the surrounding peaks were scrambled when we wanted a quieter day or the weather looked less settled.

Mitchell Peak, 3,804m or 12,482 ft.

This stands opposite Pingora and flanks the Jackass Pass. It has steep faces to the north and west with rocky ridges breaking the southern slopes above the pass. The normal route starts by crossing the Popo Agie River to the north by Lizard Head Meadows and circling round to the eastern side. We had though read of a rough winding route starting from the pass. From our camp we traversed a minor hump to reach the Jackass Pass (also called Big Sandy Pass) picking out potential ascent routes on the way. A vague track through the lower grassy slopes vanished once we started on the talus (boulder field). Turning a ridge by a traverse right and entering a gulley we made good progress to a scramble up a small ridge with a stunning finish (I, 3rd class). A move onto a block left one peering nervously down over the apparently overhanging north face. A right turn and gentle scrambling over blocks took the three of us to a broader ridge and shallow Cairngorm-like boulder slope and a rocky granite summit. A worthwhile ascent. A bite to eat and we needed to move on as the weather looked as if it would deteriorate as forecast. Rather than descend the ascent route we looked west and the normal route appeared reasonable. After a 100m or so south we scuttered down a rock slab (I, 3rd class) to find a stony slope to the col towards Dog Tooth Peak. The descent into the corrie above Lizard Head Meadows was initially steep and loose but improved to a rough grassy slope. A long descent left us on a rocky outcrop, peering over mature pine forest trying to find a way on. A way was found through the trees by following recent moose tracks and trusting we would not run into the rear of the beast. On reaching the fast-flowing turbulent river we turned upstream and after a mile or so found a place where we could step across between boulders and gain the North Fork Trail back to Lonesome Lake and camp. We suffered only a few spits of rain but there had been significant rainfall elsewhere in the range. The Winds’ prolific photographer and climber, Finis Mitchell, climbed the peak eleven times between 1923 (aged 21) and 1973 and placed a plaque by the summit to mark this achievement. The peak is named for him.

Camel’s Hump 3,821m, 12,537ft

Though technically a day to recover between our exertions on Wolf’s Peak and the long walk out, it seemed a shame not to try and take in another one of the magnificent mountains of the range. Sadly Anno Domini struck down two and only one made it to the top. Described by the guidebook as a 3rd class scramble, the Southwest Slope route up to the twin summits of Camel’s Hump provided a series of interesting problems. Richard soloed the unmarked route which followed a series of inclined ledges up the face with a short bouldering-style wall encountered at each step between levels. The ledges, noted in the guidebook as ‘conveniently slanted’, have just enough friction against your boots for the angle to stop you sliding – although it takes a while to convince one’s body that this is the case. The top provided both superb vistas of the previous week’s routes and an excellent ridge scramble between the humps. Lizard Head Peak (3,914m, 12,842ft), the highest in the area, was tantalisingly close separated only by a fantastic looking airy ridge climb (West Ridge, 4th class). However, low energy reserves and no company meant it awaits another visit.

Backpacking from Elkhart Park

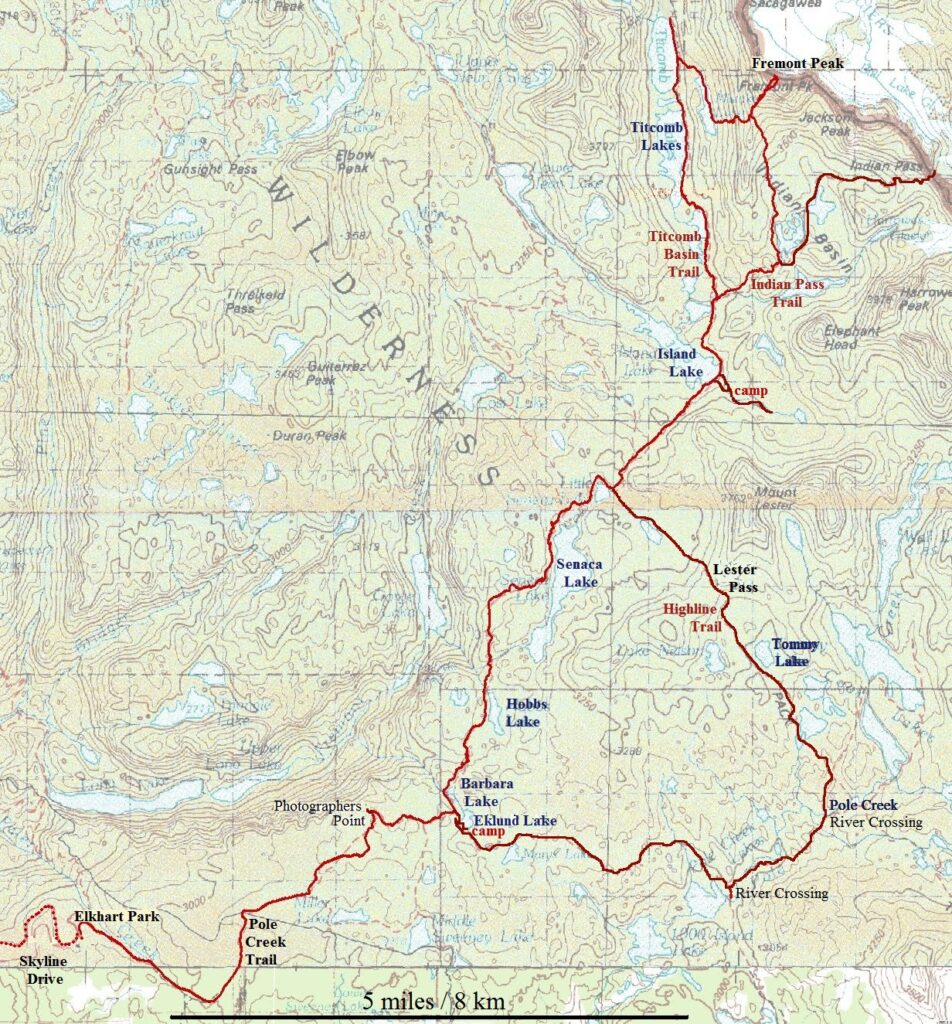

After operating as two separate groups in the east, the five of us reunited for a backpacking trip from Pinedale in the west into the high, narrow valley of Titcomb Basin. Another early start and we had driven the 40 minutes up Skyline Drive to the Elkhart Park trailhead and were surprised to see so many vehicles there. By 8am we were laden and walking along the Pole Creek Trail. The trail wound through pines and small lakes gently rising to Photographers’ Point. This cliff edge’s extensive views over the Bridger Wilderness gave us an excuse to pause

From here the clear and well signposted trail starts to cross the grain of the land with repeated rises over small ridges and drops to lakes. We met perhaps thirty backpackers in twos or threes making their way out from Titcomb Basin back to the trailhead. They reported heavy rain showers the previous day. Often people camp near Seneca Lake but we pushed on past little Seneca Lake and two minor passes and descended across snow patches to the head of Island Lake. Mosquitos were a problem by the lake so we went steeply up the slope to the southeast and camped by a fast-flowing stream on a tree-lined cliff top. This gave good views, had a breeze, dry pitches and proved to be a good site.

The big attraction of this area is Titcomb Basin and its views of towering peaks and we set off for that the next morning but increasing cloud by the time we reached the turnoff to Indian Pass caused us to switch plan and head for that pass. Richard had passed the same junction earlier having left camp at 6:30 and carried on into Titcomb Basin then scrambled up Fremont Peak to the north in demanding conditions (described elsewhere) to make the most of his one available day before he had to head back home. The remaining four of us wound through the steadily rising trail past the lakes of Indian Basin. Turning east first through marshy ground below snow slopes then over those slopes and screes we eventually reached the pass, 12,140 ft on the Continental Divide. Looking back over the terrain we considered the route ingenious and appreciated why the more direct route had been avoided – snow slopes and steep rock slabs made that way impassable. At the pass we caught up with a heavily laden couple who were about to head down Knife Point Glacier; it would be a day or two before they would hit another decent trail. The female half was so intent on keeping her footing on the snow slope that she was unaware of David’s approach and was so startled on realising he was there that she shrieked and dropped her trekking pole. Perhaps she though he was a bear – well, he had been backpacking for a couple of weeks. We returned by the same route to make it a nine-hour day of about 11 miles. Brief morning rain caused us to put on waterproofs for the only time in the three weeks. The afternoon gradually brightened.

Fremont Peak 4,189m, 13,745ft

During the walk in to Island Lake, Freemont Peak stood out on the horizon. With time against Richard before the end of his trip he wanted to see as much of this new part of the Wind River Range as possible. His route took him first up into Titcomb Basin – its lakes reminiscent of an Alpine valley – before heading northeast from the 10,575ft Lake’s east shore through a notch to Mistake Lake. It was at this point while descending slightly that Mistake Lake justified its name as a loud rip emanated from his trousers…. ventilation was not be an issue for the rest of the trip. From the southern end of Mistake his route went southeast up the main rock gully to gain Fremont’s southeast ridge via a saddle at 11,900ft.

Joining there the main path and, with the damp weather more reminiscent of a Munro ascent, Richard started up the Southwest Buttress scramble (class 3). Once into the scramble, the path is not clearly defined and the grade/exposure of the scramble varies significantly depending on the route picked up the ridge (up to class 4 on the slabs towards the right). Thankfully the grippy rock and intermittent clearing of the clouds allowed him to work his way up and enjoy the challenge of the slabs. With the mountain to himself, the top was identified by a long canister securely wedged between the two topmost prominent blocks. During the brief time on top waiting for gaps in the clouds to reveal the view, every weather was experienced. It is easy to see why this mountain was believed for so long to be the tallest in the Rockies. The descent on the loose rocks improved with each step as energy returned with the decrease in elevation. Glissading into Indian Basin and encountering yet another stunning valley with a colourful abundance of wild flowers, his knees were thankful for flatter ground.

The next day Richard was off before 8am to walk out and drive to be sure of catching his flight the next day. Those remaining had a slower start as the plan was for a more relaxing pace and less ascent on a walk into Titcomb Basin to the north. The northern tip of the uppermost lake was reached in a ten mile, six-hour stroll with many stops to admire the peaks and watch the flotilla of goldeneye on the upper lake. This time we met two Germans on a variation on the Continental Divide Trail. They were 4½ months into the south-to-north route and unsure if they would finish it this year before the winter set in.

The next day we planned to walk most of the way directly back to the trailhead to greatly reduce the following day’s hike out and allow plenty of time for the drive south. Up at dawn and packed for departure from the Island Lake camp before 8am we were soon over the two minor passes and down to Little Seneca Lake. A dilemma faced us: carry on straight back and we would finish early in the afternoon or we could take a different route new to us, twice as long and not researched, over the Lester Pass and rejoin the outward trail near Eklund Lake. The slope up to the 11,115 ft pass looked well graded and slowly we talked ourselves into this option to make best use of our remaining time in the Winds – after all we were unlikely to be returning. There were moments when we regretted that decision.

The tramp up to Lester Pass was no problem. A snow bank on the other side was descended to wind down the Highline Trail through alpine meadows to the treeline and a lake for a break. We were making good time. Then we reached Pole Creek and discovered that an unexpected river crossing was needed. All descent so far… a lot of it. Another mile or so and a second, deeper faster-flowing crossing. Then in the heat of the afternoon a long unrelentingly uphill Pole Creek Trail took us past a string of lakes including Long, Mary’s and Eklund Lakes to regain all that lost height with nutcrackers giving raucous accompaniment. It was hard work with our packs and we were tiring but we had seen two new valleys. Enough flattish ground was found by Eklund Lake where we camped despite the inlet being dry. This site was enlivened by squeaking and whistling rodents including chipmunk, ground squirrel, pikas and water shrews. A camper on the far side of the lake fished at night using a light as a lure.

The hike out the next day via Photographers’ Point was uneventful. Off by 7:15 we were at the Elkhart Park trailhead before 10am. Another grand five-day trip.

The way home

Medicine Bow Peak, Snowy Range 3,662m, 12,013ft

Following the recommendation of our Riverton host, Richard took route 130 back to Denver and with his flight not until the evening he was looking for something to keep him occupied. Although the driving distances are great, rolling along these quiet American roads is undemanding and the scenery making you feel you’re watching a Western. Route 130 traverses the Medicine Bow National Forest and many trailheads were signposted from the roadside. Travelling light (most things were packed for the flight) and with no map, he did not set a good example to the hordes of families setting off for their Labour Day weekend walks. The Snowy Range is the northernmost sub-range of the Medicine Bow Mountains, their distinctive quartzite rock creating a striking white scar poking through the forests. The walk up from Lake Marie follows (thankfully) well marked trails and follows the bare rocky ridge up the boulder strewn top of Medicine Bow Peak. With two weeks of conditioning behind him Richard was not to be overtaken. The unobstructed views from the top over the National Forest were only limited by the haze and showed that this area could keep you easily busy for a week or more. The Snowy Range is certainly worth a detour should you be passing and made a great finale to Richard’s trip.

The remaining four drove through the Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado on their return from the Winds to Denver, taking in a few short hikes.

The first of these was from the alpine visitor centre and called the Tundra Communities Trail. A gentle incline from the car park, it reached 12,310 ft in just half a mile and gave hazy views of the surrounding peaks besides the alpine zone tundra flora and fauna. Later the same day we braved the crowds above Bear Head Trailhead to hike the wide trampled trail past Bear, Nymph and Dream Lakes to Emerald Lake for its views of Flattop Mountain, Hallett Peak and Glacier Gorge. Returning down the same trail made a 3½ mile round with a rise and fall of 700ft. Towards sunset, on the drive back down to Estes Park, a detour took us to a flat-bottomed side valley where family groups of elk grazed near Moraine Park. The following morning a circuit of Lily Lake was used for a mile of exercise before a long drive. It was undemanding though we saw climbers heading for the rocky ridge above it.

Attendees:

Michael Smith, Alan Kay, David Hick, Richard Smith, Tim Josephy

Some critters encountered:

Leave a Reply