Solitary Camping On Scafell

By Percy Lund

For years, the wild scenery of the Scafell range had exercised a fascination over me. One or two short visits, at long intervals, had roused my enthusiasm in particular for the beetling crags abutting on Mickledore and set my heart longing for a closer acquaintance.

For a long time, too, I had felt that the ordinary knowledge of a British hill, obtained between breakfast time and table d’hôte was most imperfect and unsatisfying, not to reckon the waste of labour involved in toiling up three thousand feet just for a formal visit of an hour or so at midday, and then tearing away down again.

With these ideas in mind, then, and also a desire to see sunrises and the wreathing mists of early morn from those heights; to wander over rough and smooth more leisurely and observantly than usual, I determined to live out for a few days high up on the mountain side.

The camper is usually understood to be a gregarious species, in which case I may, perhaps, claim to be a special variety, for I had no companion whatever, not even a dog. In fact, I cannot really call my expedition camping at all, for sleeping out under a natural rock shelter, hardly large enough to be termed a cave, is comparable rather to the tenement of Diogenes than to life in a tent – usually associated with numerous conveniences and a circle of jovial companions. I must confess, however, that I expected to find solitude one of the charms of the outing. I did not want a companion, but preferred to experience absolute loneliness in order to ascertain the feelings which such a state would arouse in the mind. Lastly, I decided to carry up my kit without assistance, to be throughout, in fact, entirely dependent upon myself.

Perhaps I had better enumerate the main articles in my outfit, as a guide to others who may wish for a similar experience. First, a sleeping-bag of mackintosh, with a loose lining of woollen cloth. It measured about 5 ft. 4 in. in length (not including a sort of hood extension for the head) and 3 ft. 4 in. in width, and weighed exactly 51/2 lbs. When folded it occupied but little space, and served as a wrap for other articles which were tightly strapped therein. Then came my camera, a half-plate, which, with tripod, plates, and other accessories, turned the scale at I6 lbs.–a very serious item.

For food, I had bread, butter, cheese, dessicated soups, hard boiled eggs, cocoa, tea (in tabloids), condensed milk, sugar, salt, etc., but no fish, flesh, or fowl. A tin pan capable of holding rather over a pint, three bottles of methylated spirit, a spirit lamp, and what is known as a metropolitan heating bottle ; a knife, spoon, cup, towel, and a small lantern completed the list. When the food, utensils, and apparatus had been packed, partly in the sleeping-bag as previously mentioned, and partly in a rucksack, I found the whole totalled up to within an ounce of 40 lbs.

To secure all this luggage on my bicycle and convey it over the first five miles of the journey from Grasmere, whence I started, to Dungeon Ghyll, near where the road ends, was no easy task; but with the rucksack on my back, and the well-packed sleeping-bag on the carrier behind, the tripod on the handle-bar, an alpenstock sticking out in front like a spear, and the lantern in one hand, I managed to get everything on board.

After one or two desperate struggles, I reached the saddle and rode away, not in the best of styles I fear, for my nailed boots were much wider than the pedals, and I was in momentary expectation of the tyres collapsing under such an unusual weight. But all went well. At Dungeon Ghyll I unloaded the bicycle, leaving it at Middlefell Farm, and strapping the sleeping-bag and its contents on to the rucksack, and the tripod on to that, I put the whole upon my shoulders and strode away along the path that leads over the alluvial flat of Mickleden, to the foot of Rossett Ghyll.

It took over an hour and a half of real hard work to reach the top of the Ghyll, but the steepest ascent being then left behind, I went ahead much quicker over the undulating ground to Esk Hause. Thence to the summit of Scafell Pike is no great distance, probably not much more than a mile and a half, but the chaos of huge blocks with which the last mile is littered made progress with my heavy load very laborious, and called for a good deal of care to avoid slipping and barking my shins.

From the summit Cairn on Scafell Pike, I descended a good half mile of similarly rough ground to Mickledore, and then shuffled down the steep scree on the Wasdale side for two or three hundred feet, until I came to the big fallen rocks at the foot of Pikes Crag. It was among these that I hoped to find a recess large enough to afford protection against the elements, where I could lie down under cover at night. A few minutes’ scrambling search revealed a place where two or three of the great stones had rolled together and fashioned a cavity that appeared to provide such rude accommodation as one could expect. Within, there was a sort of trough in the “basement” where one could just manage to lie down, though not to stretch full length, and above a series of irregular ledges that might serve as shelves on which to store my eatables, etc.

Of this rough shelter I forthwith took possession, preparing for my stay by making the place as habitable as circumstances would permit. I built a small wall of stones and turf to reduce the entrance a little, and did my best to level the floor of loose stones. One obdurate block at the far end of the trough would not budge more than an inch or two, so after repeated efforts I was obliged to leave it in situ, and use it as a pillow. This curtailed the space so much that when I lay down my feet pressed against the other extremity of the “bed,” and necessitated the knees being bent, whilst there was an inconvenient absence of head room. I gathered what moss I could find near and used it to level up awkward holes between uncomfortably projecting bosses, and to close up the numerous crannies around the sides of my shelter, so that it might be more or less draught-proof. Finally, I improved the shelving with the addition of several flat slab-stones, and arranged my eatables and simple cooking utensils upon them.

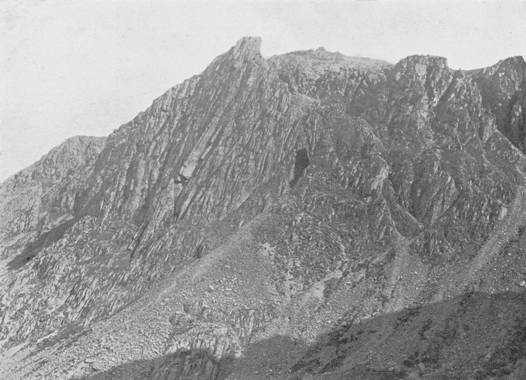

By this time the sun had sunk low, so reflecting that there would not be time to go any distance from the shelter before nightfall, I fetched a supply of water from a spring some fifty yards away, and prepared “high” tea. Whilst the water was boiling, I stepped out on to the platform at my door, and leisurely surveyed the surrounding landscape. The autumn day had been fine, but hazy, with occasional gleams of sunshine. Now a great bank of dark cloud hid the sun from direct vision, but it shone upon the distant sea and turned it to molten gold. In front of my cave, and far down, the mountain side was littered with great stones, and beyond this silent multitude, where the ground fell more rapidly, the stream, of which my spring supplied the headwater, had carved a steep-sided valley in its course down to distant Wastwater. The lake lay gloomy and still in the shadows of the desolate hills that hemmed it in, contrasting singularly with the sea far beyond. A magnificent arena rose behind me. The gap of Mickledore was in the centre, Pike’s Crag, with its , shattered ledges on the left, and on the right the still higher and more forbidding crags of Scafell; aréte and chimney, buttress and pinnacle, towered seven hundred feet above me, in some places sheer, in others broken by ledges like a giant’s stairway. They looked absolutely insurmountable, but I knew that many a cragsman had learned their inmost secrets and scaled dizzy ledges on their almost perpendicular walls. A pair of ravens circled round the precipice’s serrated top, and croaked lustily, rather than dismally. I turned in for tea, sitting on a stone at the mouth of my cave. By the time I had finished it was dusk, and a searching breeze had sprung up that found out the unclosed crannies of my rock house, and proved it to be draughtier than I liked. Peeping out for a last look before retiring, I saw the Scafell Crags dimly silhouetted against the sky, but now and then partly obscured by driving mist. Probably not a human being was within a radius of more than two miles!

It was nearly eight o’clock. I took off my boots, crept into the bag, and blew out the candle. The breeze whistled through the crags overhead, and once I heard a large stone roll down the scree. I dozed at intervals, then suddenly became wide-awake. Surely morning had come! No, the stars were twinkling in a clear sky, and striking a match I found it was but two hours past midnight. My limbs were cramped and cold, and the bed wofully hard and knobby. There was not enough moss either to make it soft or to prevent the greedy rocks from drawing the heat out of my body. But I slept again, and woke once more with a start. This time the dawn really had come. I drew myself out of the bag much as a snail creeps out of his shell, and sleepily prepared some hot cocoa.

The next business was to dress, a much shorter performance than usual, since it simply consisted of putting my boots on. Cold and damp they felt too, but I hurried out on the platform to stretch and stamp about until the blood flowed freely and I found myself thoroughly awake. It was a glorious morning, the sun not yet risen, however, but clearer than the previous day, and not a breath of wind. After drinking the cocoa and swallowing a few mouthfuls of bread, I took my camera and set off up the scree towards the Pike. Just as I reached Mickledore ridge, the sun showed his blazing face over distant Bow Fell. In a few minutes I had scrambled over the boulders and stood on the summit, congratulating myself on being an early bird for once at any rate. There was a clear prospect for perhaps ten or twelve miles, but all beyond was lost in a faint haze, the seashore being just visible. From the direction of Helvellyn light fleecy clouds were being wafted slowly towards Scafell by a very slight breeze and meeting others that were forming on Esk Hause, in the hollow of Sty Head, and on Green Gable. Great Gable stood out clear, the sun just tipping its peaked top with light, but while I gazed a beautiful fleecy cloud formed upon its breast, and then moving slowly away across Hell Gate and the sharp ridges of the Napes, vanished in thin air above Kirk Fell.

These were the very effects I wanted to see and photograph, so I lost no time in getting to a place of vantage on the plateau below the summit and erecting my camera. The accompanying illustrations show two stages in the formation of a cloud. The warm air rising from the great hollow of Wasdale was being condensed and made visible at a height of some two thousand five hundred feet. Gradually the fleecy mass increased in volume,[1] and in less than a quarter of an hour the mountain became almost lost to sight, even a portion of Lingmell near to where I stood being partly covered. Then a gentle current of air carried the great cloud away, and the performance began anew. I watched it for nearly three hours, and then returned to the shelter for lunch — a sort of Irish stew of baked beans, “Maggi ” soup, etc. The rest of the day was occupied with a leisurely scramble up Scafell by way of the Broad Stand, thence down Deep Ghyll, and out by Lord’s Rake.

Late in the afternoon, a solitary wanderer passed right in front of my shelter without suspecting its existence. He carried a sledge hammer on his shoulder, and from a satchel behind I saw a smaller hammer projecting. These implements proclaimed him a geologist. I hailed this stone-breaker, and he turned back with some astonishment when he saw my house, but set to work in good style on the boulder that I had vainly tried to move, soon reducing it so much that between us we rolled it out of the chamber, and my heart rejoiced in the thought of being able to stretch myself at full length during the coming night. He also knocked off two or three sharp corners of rock that had not merely interfered with my comfort, but had already torn one or two holes in my coat. To him also I owe the photograph of the shelter and its tenant, for I had no means of photographing myself.

When he left me, I gathered more moss for my couch, and still further reduced the size of the doorway, for the evening was chilly, and I did not look forward with much pleasure to the prospect of another cold and almost sleepless night. There had been a repetition of the golden sunset effect and the same glittering sea, and as it faded night crept on apace. The dark crags overhead became blacker, the lake merged into the sky, and soon nothing was to be seen but the big angular blocks close at hand-fellows of those that formed my cave, and children of the same great mother crag.

I crept into the bag once again, and after somewhat ineffectually trying to dry my stockings on the lantern, I drew them on, and prepared a cup of hot cocoa previous to lying down.

Notwithstanding the smaller opening and softer bed, I suffered more from cold during the second night than the first. The reason for this was plain next morning, when I found the ground white with hoar frost. The temperature had fallen to freezing point. Oh for a sack of dry hay or brackens! It was evident that without a bed of some such non-conducting material a comfortable and sound night’s sleep would be out of the question. Before the succeeding night I descended to where brackens grew profusely (fifteen hundred feet lower), and cut as many as I could carry in the focussing cloth. I also dragged a small supply of wood up to provide a fire at which my clothes could be dried in the event of a wetting.

Notwithstanding another night of little sleep I rose once more “about the springen of the day,” as Chaucer calls it, and enjoyed the cool, fresh air of the new morning.

I walked along to the top of Lingmell, the biting cold breeze from the north-east making me sharpen my pace. No vestige of cloud could be seen. Before me lay Borrowdale with Derwentwater beyond, and Skiddaw and Saddleback sharply defined on the horizon. Looking backward towards Scafell Pike, I was surprised to find the mist drifting over it at frequent intervals, coming it seemed from nowhere, and vanishing mysteriously in thin air.

Not a sound could be heard; not a living creature was visible. Indeed, I was struck with the astonishing absence of life during my few days’ sojourn on the mountain. Sheep I saw only occasionally, a few pairs of ravens, and now and then a stonechat; but these and a number of beetles exhaust the whole category of animal life. As to human beings, I met several on the first day on the way up; a Scotsman on the second day, who was investigating some of the climbs; also the geologist mentioned previously, and twice or thrice I saw or heard people in the distance. But before midday and after about four in the afternoon not a soul came within sight or sound of my solitary shelter.

As I loitered about the rocky slope that lay around, I noticed that the wind had changed, and was now coming from the south-west in that mournful, fitful way which told ‘ only too plainly of impending rain. At sunset came the first few drops, splashing in at my door in the most disconcerting way imaginable. I noticed, too, for the first time, that I was very imperfectly sheltered on the south-west side, and if the rain fell at all heavily, especially if accompanied by a fresh breeze, my cave would rapidly become most uncomfortable. Besides, I had secret misgivings in regard to various crannies and slopes of rock forming my back wall. It seemed as though the waterproof quality of my sleeping bag would now be thoroughly tested, and I had visions of certain shop-windows where I remembered having seen little tin ducks floating about merrily in an artificial pool formed to show the excellent nature of the material in which it lay.

Against moderate rain I had no doubt I was fairly well provided, but there was no question about it I should be in a mess if a genuine lake-country downpour came. As a partial defence against wind-blown rain, I stretched my focussing cloth across the doorway, and fixed it firmly with a long piece of timber that I had brought up that afternoon, plus my alpenstock and numerous small stones. Feeling more secure I spread the bedding, wishing I had three times the quantity. Thanks to the warm brackens sleep soon overtook me, and it was broad daylight before I awoke.

All seemed pretty dry inside, but on looking out I saw that rain was falling gently and all around was blotted out by a thick mist. Then I began to feel the inconveniently small dimensions of my “hotel.” Since the roof sloped rapidly towards the floor, making caution essential in lying, down and rising to avoid giving one’s head a nasty knock, I could not stand upright excepting just at the entrance. My usual seat was the doorstep, but that was now too wet to be used.

Waiting hopefully an hour or so I found the weather getting steadily worse instead of better. Raindrops pattered on the rock roof and trickled round inside till they could cling to the roof no longer, and then they fell-upon me. At the outer shelving side water was oozing in and running down to the bedding. I tried the experiment of lighting a fire in one of the crannies to keep the place as dry as possible, but all the smoke drew inwards and well-nigh choked me. One learns by experience, and I saw clearly that with two or three yards of tent-cloth to fasten well over the entrance and down the side the wet could have been kept out altogether. I decided to wait until noon, and then if there were no signs of an improvement, to eat a good square meal and “trek” homewards.

At noon it rained still faster, so I prepared the best of my food, threw the remainder away, and set to work packing up. This proved a most uncomfortable operation in the confined space, but at last all being well secured, I stepped out into the rain and mist shortly after two, shouldered my baggage again, scrambled up the Pike, and after missing my way down on the other side in the thick mist, and having to return to the top and start afresh, I struck the track again and pushed along at a fair speed.

Wet to the skin, and buffeted by the wind, till three hours after setting out, the farmhouse at Dungeon Ghyll came in view. There I mounted the bicycle once more, and ploughed on through mud and mire to Grasmere.

And so my solitary sojourn came to an end. But as soon as the winter’s snow has disappeared I shall again set out to the lonely rocks below Mickledore, and, prepared with ampler provision against rain and wind, make a longer stay amidst the wreathing clouds and in the shade of those towering crags that build up the “high places of the earth.”