Jockey Hole And Rift Pot

By T. S. Booth.

The fascinations of pot-holing do not appeal to all. A considerable number of the members of the Club are not attracted by it; it can hardly therefore be wondered at that unfortunate outsiders listen to our pot-holing tales with mingled curiosity, wonder and – at times – contempt.

Rarely, however, does a man join an expedition for once only. Let him but listen to the voice of the charmer, get to the bottom of a pot of even small interest and he is an enthusiastic pot-holer forthwith. Seldom afterwards can he resist the temptation to look up his besmirched garments, and go forth, either to conquer new subterranean worlds or revisit the scenes of his former exploits.

To one usually engrossed in business cares and worries pot-holing comes as a complete change and, almost incredible though it may seem to those who have not indulged in it, there is no greater relief from brain fag than to set out for a pot-holing week end with genial comrades.

On May 21st, 1904, a party consisting of Messrs. Blûm, Buckley, Brodrick, Constantine, Cuttriss, Green, Hastings, Hill, Moore, Parsons, Swithinbank and the writer arrived at the New Inn, Clapham, well provided with tackle, and with the exploration of Jockey Hole as their object.

The Hole is somewhat out of the ordinary pedestrian’s track, being about a quarter-of-a-mile north-east from the top of the Scars at the head of Clapdale.

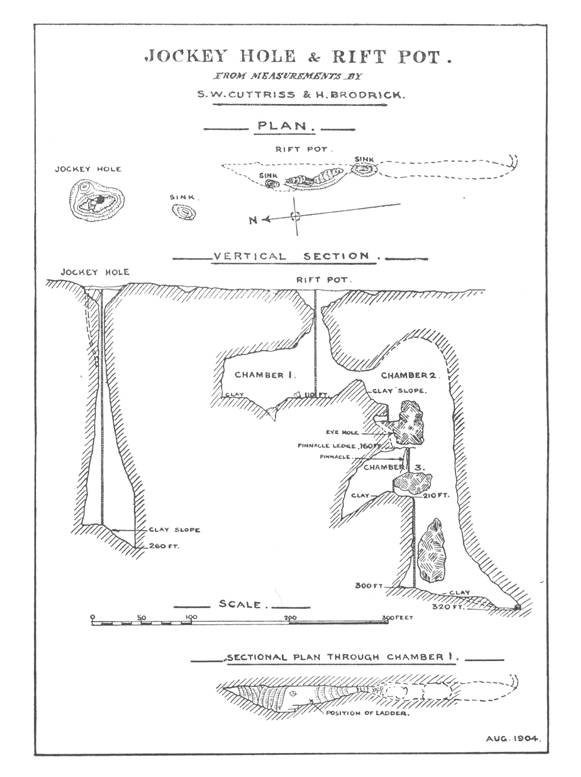

A slight depression surrounds it, and a steep slope leads down to the opening of its nearly circular vertical shaft. The northern part of the slope is blocked by a large rock which some years ago became detached from the western face and jammed itself across the hole.

Our tackle was carted from the Inn to a spot about a quarter-of-a-mile from the Pot; the party then carried it the remaining distance and began to make preparations for the morrow’s work.

Early next morning a start was made from the hotel. Our walk was through the lovely and secluded village, and up through Mr. Farrer’s well kept grounds.

Clapham is at all times, in my opinion, the prettiest village in Yorkshire, but on this occasion it seemed to surpass even itself. The banks, here golden with primroses, and there purple with wild hyacinths: the trees in early spring-tide beauty: the rippling stream, with the white limestone scars in the background: all combined to render the scene most charming. Indeed, such attractions made even the most ardent pot-holer pause and question his own taste in leaving so much beauty to seek the gloom of the underground.

Not without some regret our progress was continued, the Hole was reached, and work begun. Rope-ladders were tied together, one end fastened to a stake driven into the slope, and the other end lowered into the hole. A man climbed down the ladder to a ledge about 20 feet below the surface, where he remained to form a communicating link between each man who afterwards descended and the men at the surface who manipulated the safety-rope. Another man then followed, and on reaching the last rung some 200 feet down and finding that he was still some distance above the bottom of the chasm, which was now clearly discernible, rather than waste time and energy by returning, he asked to be lowered bodily on the safety line and so completed the descent. This rarely-used method proved by no means comfortable. Immediately on leaving the ladder the additional tension put on the already fairly taut life-line by the whole of his weight caused him to drop six or seven feet. This was succeeded by a rebound, the whole action strongly reminding him of childhood’s days and a ‘Father Christmas’ on a piece of elastic. When, too, his estimated depth of I5 feet from the bottom end of the ladder to the floor of the pot-hole proved to be 40 feet instead the experience of this method of descent proved far from agreeable to him.

To misjudge depths, not to mention distances, is a common mistake to make below ground, it being difficult to form even approximately correct estimates in the semi-darkness which prevails. Extra care ought therefore to be exercised when leaving a ladder in the manner related, and especially on a long rope.

ln order to avoid a repetition of the unpleasant dangling process the ladder was then lowered until the bottom rung was within 8 feet of the floor of the hole, the top being some 50 feet from the surface. By this means the descent was safely continued and the leader was soon joined by his comrades.

We had descended a beautifully fluted perpendicular shaft about 210 feet in depth, the sides of the upper portion of which looked particularly weird when viewed from the dark depths below. Towards the bottom, where it contracted in width, a shower of water falling from the sides made the descent somewhat uncomfortable. We had landed on a clayey slope, down which we now proceeded cautiously and were soon confronted by a perpendicular wall of what appeared to be wet clay and rounded stones, which barred further progress. The depth from the surface was here found to be 260 feet.

We looked carefully for any outlets, but with no result. Somewhat disappointed the party prepared to return; but as the last rung of the ladder hung about 8 feet overhead the life-line had to be climbed that height before it could be reached. This did not end our difficulties, for after the 150 feet of ladder had been re-mounted the explorers were informed by a friend, comfortably ensconced on a ledge just above, that a further 10 feet would have to be climbed hand-over-hand on the rope with which the ladders had been lowered. One member of the party while ascending the ladder found that the end of the safety line which had been lowered for his use had got threaded between two rungs. He was therefore compelled to take the line off, disentangle it and tie himself on again a no-very-comfortable or easy task in such a situation. He was rewarded for this feat by having to stay on the small ledge 50 feet from the top for five or six hours, directing the others and acting as a communicating link between the men above and those below.

While one man was still at the bottom an awful crash as of falling rocks was heard by the party at the top. Receiving no answer from the men on the ledge as to the cause or result of this it was feared for a few moments that someone might have fallen from it, and immense relief was felt when it was found that nothing dreadful had occurred. A stone of no great size had fallen from below the ledge, dislodged larger ones in its descent, and thus occasioned the alarm. Fortunately the man at the bottom, hearing the stones coming, had rushed to the southern extremity, and from that place of comparative safety observed the falling masses strike the very spot where he had been standing but a moment before. Notwithstanding the shock he experienced, he quickly regained the surface, where he was received with the cordial congratulations of his comrades.

Thus ended our exploration of Jockey Hole. Generally, we were disappointed with it. From its appearance above and during the progress of our descent we had had hopes that it would lead to passages of no mean importance and size; but, as is not unusual, these expectations were not realised. It was about noon when all the members of the party regained the surface, and having the greater part of the day still before them it was decided to explore an un-named pot about 20 yards south of Jockey Hole.

Its unpretentious surface appearance would have made it difficult to find, but its relative position to Jockey Hole had been carefully located previously.

It is a fissure in the Fells measuring about 10 feet by 60 feet at the surface. At each end there is an easy slope downwards for about 30 feet, where the top of a perpendicular shaft is reached. This shaft we had previously plumbed and found it to be 112 feet deep from the surface.

Our rope-ladders were soon lowered, and four men descended and found the shaft gradually opened into a chamber about 150 feet in length and lying practically north and south. At its southern end was a bank of fallen stones. Climbing this they came to a clay slope which led into another chamber. As further progress here seemed to be difficult, and required more time than the men had at their disposal that day, it was decided to return.

Next morning an earlier start was made every member of the party being full of expectation. Within half-an-hour of reaching the Hole six men were at the bottom of the first shaft. On arriving at the top of the clay slope, which had been the furthest point reached the previous day, one man took up his station there, while the others climbed down to find that they were now in a gradually descending passage, the floor of which was perforated with holes through which dislodged stones fell with a sound indicating a great depth. A pitch of about 25 feet followed, which was descended by means of a ladder we had brought along.

It was now seen that the floor of the second chamber had been reached, and by throwing stones around we gathered that there were several outlets from it. One of these, over a wall about 20 feet high, was reached after a rather stiff climb by one of the more expert members, who then was stopped by a vertical shaft of perhaps 150 or 200 feet in depth. Having no ladders any attempt to descend this was out of the question, so it was abandoned and other openings were examined. By traversing a ledge of rock directly underneath the clay I slope a passage some 4 feet wide and 6 feet high, descending at an angle of about 45°, was discovered. In this there were several pitches of three or four feet each, and as the leader found it necessary for safety to shift the masses of loose stones which lay on the slopes here, volleys of them went crashing into the depths below. His efforts to remove all were in vain, for he could find no solid foundation. Nothing daunted, the party, keeping close together to avoid accident from the dislodged stones, descended the sloping passage slowly for a distance of 40 feet or so, when they were brought to a standstill by a vertical pitch of about 12 feet. This was avoided by wriggling through a small hole dubbed “the Eye,” which opened into a little recess beneath where we stood, and which afforded barely sufficient room for three men. Pursuing the descent from here, and still over extremely loose stones, another large chamber was reached, high up on the east wall of which the party found themselves perched.

Since leaving the second chamber progress had been very slow. Every step had started a shower of stones; the leader, consequently, had been the greatest sufferer, having had a lively time fielding them. About 20 feet below ‘the Eye’ a drop of 30 or 40 feet was reached, which again brought the party to a temporary standstill; but, by creeping round a very awkward corner on a narrow and outward sloping ledge, above which the rocks overhung and barely left room for a man to crawl, the top of a pinnacle of rock was reached about five yards along the ledge. As this seemed a suitable place from which to continue the descent the expert climber’s services were again called in request. Leaving one man on the ledge the others made the somewhat difficult descent in turn and examined their new surroundings.

They appeared to be on the floor of a third chamber, one side of which they had climbed down; but, on closer examination, the floor proved to be only another mass of jammed stones forming a broken platform about 40 feet long by 20 wide. A stone thrown from the southern end of this platform fell over 130 feet before striking the bottom. At the north end there was a much less fall and this was negotiated by a bit of difficult climbing. Still another floor was thus reached and, descending a short slope leading in a southerly direction, another drop – this time of about 120 feet – was encountered. Without ladders and more assistance no further exploration could now be made, so a return to the surface was begun, the man on the pinnacle-ledge was picked up on the way, the squeeze through ‘the Eye’ once more effected, and the passage with the loose stones ascended at the cost of a few additional bruises to each man. Climbing up the ladder above the floor of the second chamber we found that the man we had left at the top of the clay slope had been sadly troubled at the tremendous noise we had made while clearing the passages below. His shouts of enquiry had, however, been drowned by the crash of the falling stones. The long climb up the last ladder to the surface and the exertion of hauling up all the tackle thoroughly warmed each member of the party, and the consciousness of their disreputable appearance on their return to Clapham in no way interfered with the satisfaction they felt with the work done.

A second attack on the Pot was commenced by a fatigue party of four on August 20th, 1904. These men superintended the conveyance of two cart-loads of tackle (including a complete camp equipment and food for three days) from Clapham to the scene of operations.

Somewhat late in the day two tents were pitched in Clapdale, about a mile below the Pot. The men then endeavoured to sleep the “sleep of the just,” but it must be confessed without much success, for the bracken with which the mattresses had been filled was provokingly uneven. The next morning was occupied in pitching two more tents and in putting the whole camp in order. The latter was no easy task, for the owner of the tents, who was expected to join the party, is a man of luxury and somewhat exacting in his demands for comfort even in camp life.

In the afternoon we walked over to the Pot, the ladders were let down, and the tackle which was to be taken forward was lowered. The party was by this time considerably augmented, and it was decided that the four men who had come up the previous day should continue the descent, taking with them the extra tackle required for the morrow. This consisted of four ladders, each about 35 feet in length, ropes, flare-lamps and sundry other necessaries, so that their progress was slow. After depositing the ladders, etc. at the spot reached on the previous expedition the return journey – rendered pleasurable by the absence of impedimenta – was made to the surface.

On reaching the camping ground a quick toilet was made at a water-trough a short distance away, and the party considerably refreshed sat down to a dinner of such excellence as is not usually associated with camp life. The repast was succeeded by a jovial evening.

Next morning all were astir by 4.30, and the descent was begun soon after.

Two of the men who had been down with us the previous day were left in the large chamber to take its measurements, and others descended the clay slope beyond in two separate parties to reduce as far as possible the risk of injury from falling stones. Progress was very slow. Owing to loose stones it took us an hour-and-a-half to descend 100 yards, during which time the men who had not been down before were duly impressed in more senses than one.

On reaching the place where the tackle had been left the previous day the extra ladders were quickly tied together and lowered down the unexplored shaft. A man then descended some 60 feet and endeavoured to reconnoitre by the aid of a flare-lamp which had been lowered. This lamp did not prove of great service however, as just at the moment when it was to have been lowered further the cord by which it hung was cut by a sharp rock and the lamp went crashing down into the abyss. Finding that the bottom of the shaft could not be seen from his ladder the explorer returned, and on a second attempt, after 20 feet more ladder had been lowered, the descent was completed.

Two more of the party then went down and found themselves in a lofty chamber about 100 feet long by 30 feet wide. At its southern extremity a steep clay slope led down into a passage some 4 feet in height, which led away eastward. This gradually became shallower until there was not more than two and a half feet in which to crawl along, and as it contained about 2 feet of water progress was a little difficult and none too comfortable. The roof of the passage was coated with scum, showing that at no distant time the exit had been insufficient to allow the water to run away and the passage had been full to its roof. Two members of the party crawled through the water for about a quarter-of-an-hour, and then, as the prospect of the passage opening out did not improve, they returned. Water-logged passages are no uncommon feature at the bottom of a pot-hole. The cave explorer generally endeavours to keep his feet dry at first, but in his enthusiasm he advances into water perhaps ankle deep. As he goes on he may soon find his knees under water, and before very long be up to the neck in a deep channel, or bent double in a shallow one and almost immersed. So long as the water does not reach to his waist he may not feel much discomfort, but when it rises above that level he feels the effects of the cold more seriously, and vitality is lowered and ardour cooled. We avoided the bottom clay slope on our way back by taking to a water-course which ran through a passage west of it, and as the cold and damp were telling upon us we hastened up the lowest ladder and reached the floor of the third chamber.

On our arrival there we were somewhat concerned to find that one of the party, who earlier in the day had had the misfortune to bump his knee against a rock, was now nearly incapacitated. Hoping to get to the bottom of the hole he had struggled down to the place where we now found him, but was compelled by increasing pain to rest there. Examination showed that the damaged knee was badly swollen, and fears were entertained as to his ability to get to the surface again unaided. However, after he had taken another rest two men were deputed to assist him. This was no easy task either for the sufferer or his assistants, but by dint of much pulling and pushing on the part of the latter and many contortions by the former the floor of the first chamber was at last reached.

As he insisted that he could climb the last ladder without help it was decided that only one man should accompany him, so he climbed the 110 feet of swaying ladder to the surface. Considering that he had only one useful leg to climb with this needed tremendous effort, and must have caused him very great pain.

It had been arranged to haul all the ladders up again in one length in order to reduce the risk of dislodgment of loose stones and to finish the work more quickly. However, generally owing to the rungs catching against the rocks and our consequent efforts to clear them little, if any, time was saved, whilst much breath and more temper were wasted in the effort. Eventually, after a great deal of hard work, all the tackle was got up and the party returned to camp weary and worn but well satisfied with the result of their expedition.

The weather on both occasions was exceptionally favourable; but the few who remained till the following day to strike camp and see the tackle away were awakened at 2 a.m. by a perfect deluge of rain, which continued without cessation for 10 hours and very much hampered them in their work.

The name ‘Rift Pot’ was given to the hole because of its characteristic form, it being literally a huge vertical rift in the limestone. The party which took part in the second and successful attack on this Pot consisted of Messrs. Booth, Brodrick, Buckley, Constantine, Cuttriss, Green, Hastings, Hill, Horn, Parsons and Scriven. The three who reached the bottom were Hastings, Green, and the Writer.