Some Reminiscences Of Skagastölstind

By Erik Ullén.

“Vallis est hic mundus mons est coelum.“

(From a 12th Century MS.)

If it be true that a special inferno awaits the climber who has ascended a mountain more than once my prospects for the future are very dark indeed, for I have been no fewer than sixteen times up Store Skagastölstind. I have been there alone and also in good company; in the daytime and at night; in sunshine and in snowstorm. Sometimes the ascent has been mere play in fun and merriment, and sometimes a fierce struggle against heavy odds, and I cannot say which we enjoyed most. I may add that I have been up Skagastölstind by eight different ways and hope to find one or two more if opportunity offers.

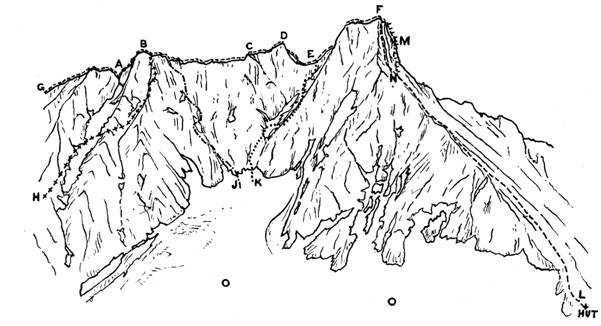

Cecil Slingsby made, as all who climb in Norway know, the first ascent of the mountain in 1876. He ascended the glacier which now bears his name, reached Mohn’s Skar ‑ the col between Store and Vesle Skagastölstind, and finished the climb by the north arête. Four years afterwards Johannes Heftye, with Jens Klingenberg and Peder Melheim, made the ascent from the opposite side entirely by rocks, and this route is now generally taken. The most interesting portion of this climb is the famous Heftye’s chimney. In 1890 Hans Olsen Vigdal of Skjolden (not to be mistaken for Johannes Vigdal of Solvorn, the well-known guide) varied Heftye’s route considerably. From the ledge below the chimney he made a traverse to the left to another chimney, which he ascended ‑ a brilliant achievement considering the sensational nature of the climb and the fact that he was alone. The big gully in the west face was climbed in 1899 by A. W. Andrews and O. K. Williamson, with Ole Berge. Dr. Brockelmann and Oberleutnant la Quiante made the second ascent by this route, and I see in Deutsche Alpenzeitung (7 Band, 4 Jahrg., p. 231) that they believed it to be a first ascent ‑ a very natural mistake considering that they had never been on the mountain before. I saw their tracks only one or two days afterwards and there can be no doubt that their route was exactly the same as Mr. Andrews’.

I made my first ascent of Skagastölstind in 1903 in company with two Frenchmen, and a jolly day it was. None of the party was a linguist, and when not climbing we were busy turning over the leaves of our dictionaries. In Vigdal’s chimney, which was very glazed, I learned many Gallic phrases which were as concise as they were expressive and which have since proved very useful. Two days afterwards, our party on Store Midtmaradalstind was composed of seven mountaineers of four nationalities and thus made it a new Tower of Babel. During the descent we got into difficulties, and I am afraid that our remarks would have been awful hearing for a Presbyterian well versed in languages.

The same summer we had the good fortune to find a new route to the right of Heftye’s chimney. It was a wet and dull day. Fröken Therese Bertheau, Kristian Tandberg and myself were sitting on the ledge below considering which way we should take. We noted with disgust that a fixed rope was dangling in Heftye’s chimney, and, as we had done Vigdal’s traverse before, we looked at the rock-wall between these two routes but did not like the aspect of it; it was somewhat overhanging and streaming with water, so we turned our attention to the right. Tandberg traversed some slabs and swarmed slowly up a vertical and exposed buttress to a considerable height and then tried to step across a shallow gully to the right.

This is the mauvais pas of the climb. The handholds are not bad, but the only available foothold is very scanty and the whole business looked rather nasty. We did not feel quite prepared to follow our leader should he take a speedy descent to the Slingsby Glacier and told him so, and, as he does not like travelling alone, he displayed great caution and eventually pulled himself safely across. It was rather difficult to find a satisfactory belaying pin but in due time we all joined our leader. From here a comfortable couloir and some easy slabs led us straight up to the cairn.

In 1904, four of us, including two ladies, succeeded in climbing the wall between Heftye’s and Vigdal’s chimneys. The wall is, as I have already mentioned, somewhat overhanging, and icy water flowing from above failed to make it more attractive. Standing on the big stone, which makes such a welcome barrier on the ledge, I could reach some rather poor handholds and get a little support for the right foot on a badly sloping boss of rock. The next movements were awkward and required care, but higher up the holds improved. A few minutes later a cry of exultation in various keys reached me from below as I clambered up to a spacious and comfortable ledge.

The first thing I did when I had recovered my breath and rubbed a little warmth into my fingers was to tell my comrades below that it was quite easy. A scoffing laugh greeted this declaration and a bass voice remarked: “I’ll eat my hat if I ever get up there.” At the moment I felt somewhat hurt by the doubt cast on my veracity, but experience has taught me to understand others’ feelings. I am thinking of a certain day on the north face of the Pillar Rock. My friend Harold Raeburn was sitting above “the nose” and I was below, and I remember well what he said and what I said. We didn’t quite agree. However he got me up at last, and from that day he has considered me an exceptionally heavy person.

To return to Skagastölstind; Fate seemed at first inclined to find for the sceptics. A shoulder from below made the first move easy, but a moment of suspense followed and then a voice, very much out of breath, entreated the leader to pull. I pulled with all my might, and the unhappy victim, slipping away from the holds, found himself dangling in mid-air. Lowered a little he or she ‑ was seized by the legs by the rest of the party below and pulled on to the ledge, amidst a shuffle of masculine maledictions and feminine lamentations. However, by means of assiduous invocations of our tutelar saints and an ingenious use of the rope all of us at last got up by the new way, with the exception of one of the ladies, who with great firmness of character declined to be cut in twain by the rope and preferred to go up Heftye’s chimney in one piece. Having reached the summit some of us withdrew to solitude with thread and needle to touch up our sartorial appearance, for even on a mountain top some small degree of decorum has to be observed.

The above climbs are all on the east face, and ought perhaps to be called variations rather than different routes. From the west or south-west there are two ways to the summit : Andrews’ gully and the S.W. arête.

Most mountaineers who have been on the west face of Skagastölstind have certainly noted the magnificent 400-feet gully which runs straight up the nearly perpendicular summit crags. This is Andrews’ gully and affords a most interesting climb.

I made my first acquaintance with it in 1905 under somewhat peculiar circumstances. I had already begun the summer’s campaign by slipping on the deck of the steamer between Bergen and Skjolden ‑ to the immense gratification of my non-climbing fellow-passengers ‑ and, as I found out some weeks afterwards, fracturing a kneecap. I made my solemn entry into Turtegro on horseback and a committee of wise men was appointed to treat the injury. They applied a bandage, ordered complete rest, then went away climbing.

The weather was perfect, the air was crisp and pure, and the sun shone from a cloudless sky. I spent the days lying on my back in the heather, enjoying the warmth, the distant murmur of the river and the many summer scents, and my happiness would have been complete had not the snowy peaks at the head of the valley been calling with a thousand voices. One day, half-a-week after the accident, the temptation became too strong, and the invalid sneaked away after luncheon and limped to the hut on Bandet. Abyssus abyssum invocat, and when I say that the hut is about midway between Turtegro and the summit of Skagastölstind I need not tell what followed.

At the foot of Andrews’ gully I changed my boots for scarpetti. The lower portion is the stiffest and may appropriately be defined as four continuous pitches with only narrow ledges between. It is a straightforward climb the whole way, only, in one or two places it is judicious to work out a little to the right. Though I have l never played ‑ or indeed for that matter ever tried to play ‑ the piano with my toes, I used to be a master in the noble art of walking on the hands. Now I had to climb on one leg: it is a very recreative exercise and involves a multitude of striking and graceful attitudes. Higher up the angle eases off. The holds are delightfully good but in places rather apt to come off, and the climber ought to test them carefully if he does not want to illustrate the Austrian Marterl:

“In 3 Sekuntn war er unten

Man hat’n gar nöt g’fundn.”

I made a second visit to Andrews’ gully one or two weeks later, in company with three others. Inspired with benevolence towards humanity in general, and especially towards the climbing fraternity, we cleared away a lot of the loose stuff. Fortunately I was leading and could thus without arrières penseés enjoy the crashes of the stones on their way to the Midtmaradal 4,000 feet lower down. Some of my friends below seemed to be unable to perceive the altruism of this action and carried on a somewhat heated discussion when they were not looking out for stones. But then some people are shockingly selfish!

Three attempts had, so far as was known, been made on the S.W. arête of Skagastölstind : by Heftye, with Jens Klingenberg and Peder Melheim;[1] by Carl Hall, with Mathias Soggemoen and Thorgeir Sulheim[2] ; and by Fröken Therese Bertheau and A. Saxegaard, with Ole Berge. It was followed to the summit on July 24th, 1904, by four of us.

A party of two tourists and two guides started simultaneously from the Skagastols hut, and we kept company with them till the ordinary way strikes the S.W. arête and then watched them disappear round the corner. The frugal luncheon was soon finished and the pipes being put back into the pockets we roped and started, the learned man as usual first, the sturdy man second to lend a broad shoulder in cases of exigency, the charming young lady third, and the reckless man last lest he should lead us into mischief by attempting impossible places.

It was a glorious day and we felt instinctively as we grasped the warm rocks that victory was to be ours, and even the clumsiest amongst us displayed the most Terpsichorean agility when the eyes of our fair lady in wonder and admiration followed his performances. The leader started straight up the actual arête. The plate facing p. 181 shows well how smooth and exposed this is. The rocks are, however, delightfully firm and reliable, and the holds just big enough to satisfy the requirements of a not too pretentious climber. As I clambered on to a convenient ledge I could not help wondering how my comrades would like this fancy bit of rock work, and my disappointment was great when I saw them ascend with ease and gaiety over broken rocks a little to the right. A long pull without any footholds to speak of and an airy promenade on all fours along a narrow ledge brought us to a little cairn marking the highest point reached by our predecessors.

A formidable-looking wall now confronted us and seemed to bar completely all further progress. With great difficulty I succeeded in climbing ten or perhaps twelve feet, but I felt that I had got dangerously near the line which, at least so far as I am concerned, separates the possible from the impossible, and so I descended again. To the right was a square-cut precipice, and we could catch a glimpse of the Slingsby Glacier and its yawning crevasses far below. To the left were some steep slabs hanging over the abyss. Here was evidently our way. On some small holds I managed to get across and round the corner. Half a dozen steps more and a narrow vertical crack was reached. The first fifteen feet of the crack were not unduly stiff, but then the difficulties became great and I dared not venture any further and even felt doubtful whether I should be able to descend again. A glance downwards revealed the charms of the I situation: a smooth rock-wall, and a slanting slab terminating in space.

As long as the rope had been moving the silence had been unbroken, but now, when I was studying the problem how to get down, I heard voices from round the corner. At first they were soft and mellow, but by degrees they grew loud and satirical. They informed me that the sitting accommodation was scanty and that time was flying fast. Did I sleep well? They should be much obliged if I would kindly inform them how long I was going to keep them waiting. But I resisted the charms of a conversation. By means of great caution I succeeded in getting down, and, continuing the traverse still more to the left, reached a spacious anchorage just as I had run out the whole length of the rope. The rest of the party soon joined me, and their long and anxious waiting was at once forgotten at the sight of a wide vertical chimney in front which evidently led to our goal. Exulting in the imminent victory we ascended it, first working straight up the middle of it and then, when the right wall became overhanging, out and up to the left. A dark and damp cave and we saw the sky-line ahead; a short gully and the last doubt vanished. Our fair lady took the lead and a few minutes later we were standing triumphantly at the cairn.

We spent three hours on the summit, three memorable, full and – alas ‑ all too brief hours. In an easy detachment did we absorb it all: the glaciers glittering in the sunshine, the glorious peaks we knew so well now far below us, the tarn in the deep reflecting grim rocky walls and blue sky, and, half awake, half in dream, did we let the eyes follow the shadows of the floating clouds wandering over the snowy wastes to a distant and unknown far away. Down there in the hazy valley our worries and griefs and all the ennui of life were waiting for us ‑ but we did not care.

The best way of approaching Store Skagastölstind is by the ridge over Nordre, Mellemste and Vesle Skagastölstind. It is the most sporting route, and from nowhere else does the old mountain look grander. The first complete traverse was made in 1902 by Harold Raeburn’s party, and I have had the good fortune to repeat this splendid climb thrice with different parties and once alone.

Prima quaeque dificillima sunt,[the first is difficult?] as we all know, but, when the traverse of the Skagastolsridge is concerned, the beginning is tedious, which is worse, and the four hours’ walk up the endless screes to Nordre Skagastölstind are known to have ruffled even the most serene tempers. A friend of mine once undertook to carry my heavy camera there: he kept his promise faithfully and arrived at the top minus coat and waistcoat, sweating prodigiously, and said that he “would never more carry any ‑‑‑‑‑ cameras up any ‑‑‑‑‑ peaks.”

But once here the fun begins. The further one advances along the ridge the narrower it becomes and the wilder the surroundings. The view of the Styggedals Glacier and the peaks beyond is truly magnificent, a chaos of rugged arêtes, hanging glaciers and mighty ice-walls, the happy hunting ground for the fearless cragsman and the earnest devotee of the ice-axe.

The ‘V’ gap and Patchell’s slab are the glories of the Skagastölsridge. The ‘V’ gap, Slingsby’s conquest, is always fascinatingly interesting and the way is, though in no place unduly difficult, very intricate. Once, when I was there alone last summer, I lost the way completely in a vehement blizzard and got into great difficulties. Patchell’s slab is accounted one of the most difficult places in the district and will, when there is ice about, test the skill and nerves of even the best of cragsmen. I had heard vague rumours of the horrors of the place and it was therefore a great disappointment on my first visit to find two fixed ropes. A few weeks later, on the way back from the first traverse of the Maradalsridge and Centraltind, we cut away the ropes, which were very rotten, and I haven’t since heard anyone complain of the place not being haute école. Once when the conditions were very bad we were nearly beaten. Patchell’s slab can however, as Fröken Bertheau’s party showed in 1901, be turned to the left by a sort of hand-traverse which is by no means easy, but where the leader can be well fielded.

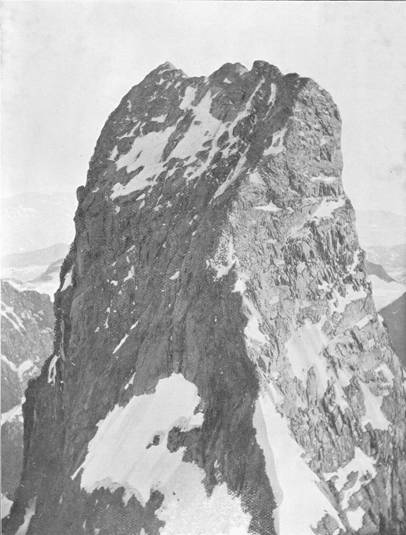

There can hardly be seen a grander and more alpine sight in Norway than Store Skagastölstind from Vesle. All around are lofty spires and white cones, but one doesn’t heed them, for the eye cannot leave this bold rock-gable. There are no delicate colourings, no graceful outlines, only this stupendous mass of rugged walls, grim precipices and gloomy chimneys, towering above the neighbouring peaks as Charlemagne above the peers. I remember once seeing it flaming red in the last lingering sunlight. We had been climbing since early in the morning, the lady of our party was quite exhausted and our progress had been only slow. It was already dark when we gained the lofty summit and day was breaking long before the valley was reached again. Another time I was alone ‑ it was two days after my first ascent of Andrews’ gully ‑ and had had a hard struggle against icy rocks and foul weather on the Skagastölsridge. I had just taken out the compass and was trying to find out the whereabouts of Skagastölstind when a storm-wind suddenly split the clouds and for a few moments I saw it looming out through the gloom. The wind was roaring wildly amongst the crags, and streams of powdery snow were blowing from the arêtes. I knew that the greatest difficulties were behind me and yet I shivered at the sight.

When our Ex-President made his memorable ascent of Skagastölstind he reached Mohn’s Skar from the south east. “On the north or opposite side to that which I had ascended,” he says, “instead of a friendly glacier or couloir close at hand, there was a grim precipice.” [3] It I had long been a dream of mine to scale this wall and thus make the first ascent of Skagastölstind from the Skagastöls Glacier, and often on the way to Bandet had I stopped and studied the problem through my glasses. The final wall looked difficult, but the foot of it could evidently be reached provided that one could get across the schrund and ascend the ice-worn rocks at the bottom. Another consideration was that stones and fragments were constantly falling from the slopes above. Of course I know that the climber ought to be able to keep a watchful eye on the falling stones, as the accomplished shot gauges the flight of the bird, and dodge them at the critical moment, but I must confess that I have utterly failed in this art though I have had many opportunities of practising it. When there are falling stones about I generally do what I do in a drawing-room when a kind friend tells me that my tie is half way up my neck: I try to look as unconcerned as possible and wish I were somewhere else. I remember what happened once when I tried to behave correctly in the matter of a falling stone. It was not a success, but that was the stone’s fault and not mine. I saw it come whizzing through the air straight at me and followed its course with the eyes of a falcon ; at the psychological moment I sprang aside and got hit right on the forehead and knocked down.

In 1903 we made what may be called a reconnaisance in force. Two of us had intended to take a novice up Skagastölstind by the ordinary way, but the weather was so bad that we dropped the idea. On the way down the glacier we decided to have a look at the rocks below Mohn’s Skar just to get a little healthy exercise before dinner; so we roped and started. The difficulties were great from the beginning, but nothing would impress our novice. He admired the view when he was supposed to be in readiness to field the man in front; discussed the great problems of humanity when engaged in a nasty traverse where a slip would have dislodged the whole party; and pooh-poohed the stones, which were now and then whizzing over our heads. “They wouldn’t do any harm,” said he, “because they were falling from such a great height,” an argument the point of which we didn’t quite catch. We spent several hours on a few hundred feet of rocks and at last gave it up, to the great indignation of our lion-hearted friend.

Late in August 1904, and quite unexpectedly, I got the chance which I had been looking for. The winter had set in early and the mountains had already begun to put on their winter garb.” My holidays were up. I had spent the day down at Fortun taking leave of friends and had intended to cross the mountains to Rosheim. It was late in the evening and Knut Fortun, my old friend and trusted comrade on so many difficult expeditions, and I were sitting in front of the cosy inn talking over bygone days. Someone happened to mention Skagastölstind and our minds were made up at once; we would attempt to climb it from the Skagastöls Glacier the following day. The odds were against us, but what would it matter if we failed? We were not going to give in without a stubborn fight and we should at all events have one recollection more to live on during the long winter months. The ropes were soon coiled, the sacks got ready, and as we started in the night a lonely star, breaking through the clouds, seemed to intimate that Dame Fortune was smiling on us.

Early in the morning we were at the foot of the rocks. There was even more snow and ice about than we had anticipated; the weather was threatening and stormy, and snow and hail fell during the whole day. We soon saw that any serious attempt was out of the question; then, having agreed so far, we roped and started, as is the way of perverse mortals.

An immense block of ice, fallen from the slopes above, made an excellent bridge over the schrund and we got on to the rocks easily. Though they were smooth and steep, the rare holds were firm and reliable, and we had soon reached a huge overhanging accumulation of old snow which blocked the way. But in the right place, just as in the fairy-tale, we found a tunnel, made by running water, through which we crawled, then broken up and rotten rocks brought us to the snow slope, which we had intended to be our highway, soaked to the skin and cold, but in high spirits.

Until now we had met with no real difficulties, but here a great disappointment awaited us. Our plan had been to ascend this snow slope with the couloir above it and try to find an exit to the left; but instead of a friendly snow slope we found blue ice covered with a layer of fresh snow. It would have taken hours of hard work to cut a way up, and the slope was swept by a hail of stones and ice-fragments. To the right was a slabby buttress where we should be less exposed to that danger, but we must cut across the dangerous slope to get there. It was however the only thing to do. Fortun relieved me of sack and coat, then five minutes of frantic exertion and we were across.

This buttress would probably ‑ though C. W. Patchell, A. Tobler and myself know by experience that the slabs on this side of the Skagastölsridge are not so easy as they look ‑ prove quite easy under ordinary conditions; but now it was something quite different. The slabs were covered with verglas and on this was a thick layer of powdery snow, so that nothing could be trusted, and more confidence had to be put in Fate than seemed advisable in this age of scepticism. Twice the treacherous snow peeled off and carried away the leader, but the second man was on the alert and held him up. At last we came on a level with the couloir. One or two attempts were made to traverse back to the left, but failed, as we put no heart in it and shirked to run the gauntlet again. So we took to the buttress again and slowly and stubbornly worked our way upwards until the foot of the final wall was reached. It was now 2 p.m.

To the left was a clean-cut precipice, and through the driving snow and sleet we could see the couloir far down. To the right the slabs merged in the face of the final peak, and in front of us was the wall below Mohn’s Skar. Was it possible to force a way up it? We scanned it anxiously, for it was our only chance and we dreaded to descend the pitiless slopes up which we had been toiling since the morning. “Messire Gaster est le père et le maître des arts” [Messer Gaster is the father and master of arts]as Rabelais says, so we sat down on a slanting ledge and ate our luncheon in silence. We were old friends and needed no words, but I could well read Fortun’s thoughts in his stern face: “You have got us into a s pretty fix!”

The sacks were soon emptied and, turning with more cheerfulness to the problem in front, we rubbed a little warmth into our fingers ‑ our gloves had long since been worn to pieces on the slopes below ‑ and started. The work was hard indeed, for every hold had to be cleared and there was not much to hang on to, but at last a little ledge was reached. It was not a comfortable place, for it sloped outwards badly and there was barely standing-room for two, but it was very welcome all the same and we gripped the only hand-hold tenderly. To the left was another ledge, which led to a corner; but the wall between was smooth and plastered with ice. My fingers were now frost-bitten and without feeling, so Fortun took the lead, for a slip must not occur. True enough, after much searching, we had found a belaying pin of doubtful security, but its utility was strictly moral, as the wall below was overhanging and the unhappy leader would, in case of a slip, find himself dangling in mid-air, while the second man was too badly placed to be able to haul him up again. It was just a place for Fortun’s iron nerves and he knew well that success or failure, and perhaps more, hung on his steady hand.

With great difficulty he managed to get a hold on the icy wall and the next moment he clambered on to the ledge, but we were both breathless. I was soon across also, the corner was reached and Fortun advanced again. The snow was whirling furiously overhead, so we must be quite close to the crest though we couldn’t see it. “What does it look like, Knut?” – “I cannot tell yet”. ‑ More and more rope went out and the excitement became intense. What if an insurmountable wall should stop us? Should we be able to get through the cornice? Then, through the roaring of the wind, I heard Knut’s jubilant voice: “Mohn’s Skar!”

Half-an-hour later we were sitting, sans cerémonie et sans crainte en frères,[unceremoniously and without fear as brothers,] behind the cairn, examining our bleeding hands and torn clothes. We were hungry and had nothing left to eat; we were chilled to the bone, and the north wind was biting; but neither the hunger nor the cold could disturb our equanimity.

Click on the list items below to highlight the route