Further Explorations In Gaping Ghyll Hole

By A. E. Horn.

After the descent made by members of the Club in 1896, no further exploration of this pot-hole was attempted until 1903.

On that occasion, Booth and Parsons followed a branch of the main S.E. passage, from which, after a crawl of two hours’ duration, they re-entered the main cavern by an opening about 30 feet up the boulder slope at the eastern end, this opening having until that time remained unobserved from the cavern.

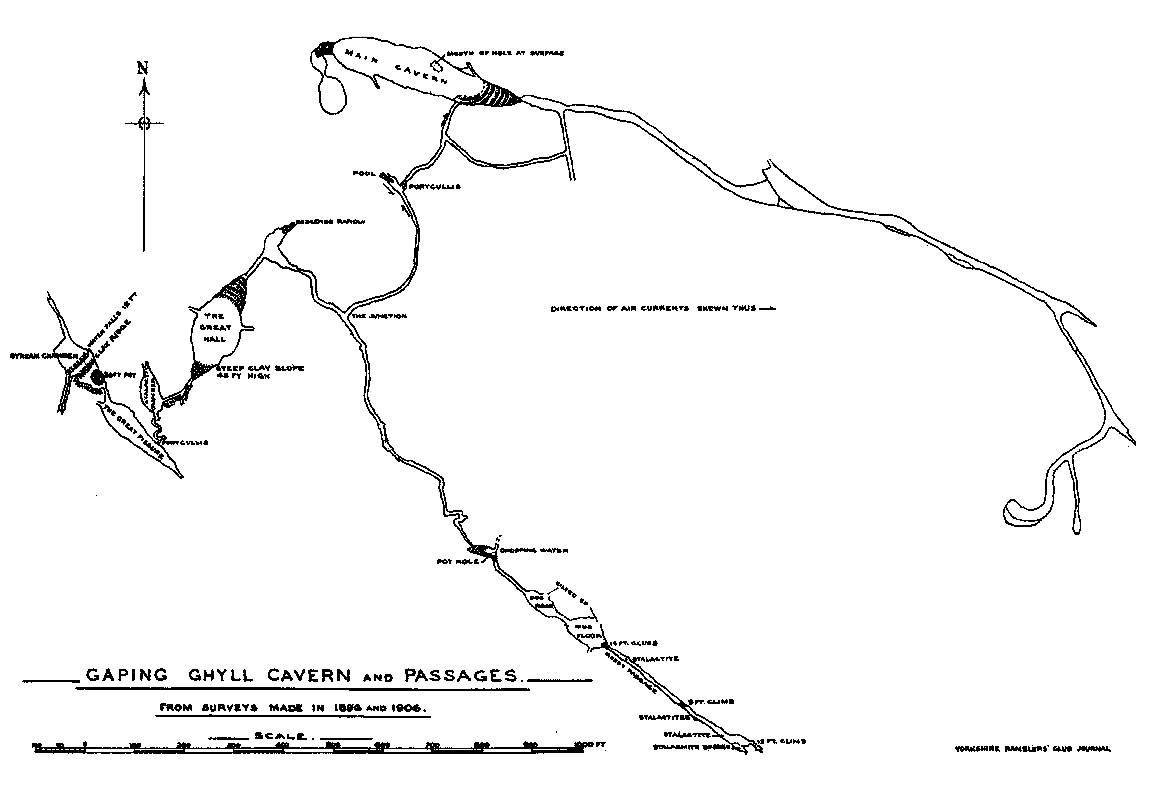

The next visit to Gaping Ghyll was made in July, 1905, and was mainly undertaken for the sport of the thing. Rope ladders were used and the descent was made by the main hole. In the course of our wanderings, however, Booth, Parsons and the writer discovered a branch opening out of the passage from which the Main Chamber had been re-entered in 1903. It commenced in a horizontal bedding plane, by a low unpromising slit and soon gave access to a more roomy passage, whence by an upward wriggle through an opening in the right wall we entered a long narrow cave running approximately N.W. and S.E. At the N.N.W. end of this cave extends a narrow water-logged fissure some 60 to 70 feet in length, bearing in the direction of the main hole. The passage out of the cave at its southern end becomes higher and more tunnel-shaped, not unlike the Cellar Gallery in Clapham Cave, bending first S.E. then S.W. until it enters, at right angles, another passage of similar character which runs S.E. and N .W. This point, some 250 yards from the main chamber, was called the “T” junction. The party here divided, Booth following the S.E. and Parsons the N.W. branch. Both returned within a few minutes and reported that they had entered more caves and there were no signs of an end to the passages. A strong draught from the N.W. branch induced us to try that direction first, and in a short time we entered, by a rapid descent, a spacious but not very lofty cave with two passages leading from it. Of these, one running S.W. in an upward direction opens into a vast hall with a fissured roof. After a descent to the lowest point of the floor a steep clay slope of about 45feet leads to a low opening close to the roof; creeping through this, along a low sandy passage, another chamber was entered. A large displaced stalactite apparently dislodged by some earth movement was passed on our right, and proceeding down a short steep slope to the S.W. we reached a stalactite chamber. The N. end of this chamber is extremely beautiful. The roof is covered with countless numbers of tubular stalactites varying from a few inches to several feet in length, and has the appearance of a shower of rain suddenly frozen ; there are also some very fine stalagmite groups. Many of the smaller stalactites are bent, mainly in a southerly direction, into most fantastic forms probably the result of the prevailing air current.

From this point, by a number of short turns, We entered a large fissure some 45 feet in height, running N.W. and S.E., its floor strewn with a chaotic mass of fallen and unstably poised rocks over which we had to proceed with care. From this fissure we emerged into a very large chamber and upon what appeared to be a platform of fallen rocks and silt. Immediately in front was a steep clay slope leading to a mud pot-hole about 30 feet deep; We traversed round it to the left and ` descended to the floor of this, the largest chamber we had yet entered. As we proceeded, a strong stream flows into the chamber on the left coming from a lofty passage perhaps 60 feet up the S. wall, and the water disappears in a N.W. direction behind a great block of detached rock, some 20 feet long, which is one of the features of the chamber. Lack of time prevented our going further as we were 500 yards from the main hole. Enough had been seen, however, to convince us that a new era in the exploration of Gaping Ghyll had commenced, and that a larger and better equipped party was absolutely necessary before the exploration and survey of this immense area could be attempted. Therefore, we rapidly retraced our steps to the main hole and climbed the ladder to the surface.

As the result of this discovery there assembled at Clapham on June 2nd, 1906, the largest party of Club members which has ever been got together for serious Work. The weather was fine, but unfortunately during the preceding Week or two there had been almost unprecedented floods in the underground streams of the district, and a great amount of Water was going down the hole. Fell Beck became an object of the greatest solicitude, and an abatement of half-an-inch of Water a matter of general rejoicing.

The jib had been fixed as on previous occasions, over the direct shaft, for descent by means of the Windlass, and rope ladders had also been put down the main shaft. It was hoped with both methods of descent available, a large number of men would be got down with some saving of time. As the men arrived they descended twenty or thirty feet on the ladders, and required no more evidence of the impossibility of proceeding further, the water and spray cutting off all view of the shaft.

For the purpose of turning Fell Beck through the lateral passage into the direct shaft, dams were constructed, but on account of the fissured condition of the stream bed, the task was not easy. More than once, portions of the stream were induced to enter likely courses down which they disappeared and eventually, by doing many most unlikely things, the greater part of the Water was diverted, leaving the main hole to drain clear.

The convenience of camping on the spot is now fully recognised and some sixteen men slept under canvas, and the camp was a scene of considerable animation. In the evening, when the party, Wrapped in many coloured blankets, encircled the camp fire, and bayed the moon, it Was decidedly picturesque. In the broad sunlight when the mud-stained clothes, relics of former expeditions, were scattered abroad, one could hardly have blamed the grass for refusing to grow.

On turning in for the night one man produced from what is now a historic rucksack, a new species of lantern with a candle projecting from the bottom. The candle dropped grease all over his pillow, then projected itself into his eye, leaving the rest of the party vainly trying to get into their sleeping bags in the dark, Our friend suggested in extenuation that we had been saved the trouble of getting up to blow out the light. We congratulated him on his automatic lantern, and wooed sleep in the resultant chaos.

Gaping Ghyll kept up its water gates for another full day, and not until the third day of our visit was it possible to make a descent. Six men then went down the ladders and the work of exploration commenced.

To anyone in need of healthy exercise and possessed of a cheerful and patient disposition I recommend a descent and subsequent ascent of 350 feet of rope ladder, accompanied by the remains of a misdirected waterfall: but to others, an electric lift. As an aid to underground exploration the rope ladder is invaluable, but as a squirming coil of unmanageable awkwardness it resembles its distant relative the snake, and has also its proverbial ingratitude. The unwillingness with which it goes down a pot-hole is only equalled by its desire to stay there. The rungs catch on even the shadow of a projection and detach loose rocks with calculated malevolence. Trust yourself to this sinuous monster and when you are going strong it will deliberately swing round and bang you against the wall or crush your fingers between itself and the rocks.

Telephonic communication established and provisions lowered, the party divided, Booth, Parsons and the writer to commence the exploration, Botterill and Hastings for survey and photography, whilst Williamson remained at the telephone.

Custom does not stale this magnificent chamber: Gaping Ghyll may well be reckoned one of the unique sights of these islands; on this occasion it was more impressive than usual. The masses of water dropping through it were torn as they fell into fantastic festoons of spray, through which bursting shells of water were continually flung.

Incessant, but strangely varied sounds echo through the chamber in rhythmic pulsations. Gusts of moisture charged air strike one. The wet, dimly-lighted walls rise into blackness, with great projecting forms of rock encircling the opening down which the daylight falls to be swallowed up in the boulder-strewn pool at the foot of the shaft.

Everything tends to awe the spectator. Alone in these weird surroundings he can, through the roar and echo of the water, imagine voices calling across the dark spaces, peopling them with spirits of the underworld.

There were many evidences that the chamber had been heavily flooded recently. A stake was found about 40ft. up the western debris-slope and recognised by two of the party as having been thrown down in 1903. A large fissure in the south wall was now more exposed and could be entered for 23 feet. The silt which in 1903 was more or less evenly distributed over the floor is now collected into a great broad bank, in places 5 feet thick, across the west end of the chamber, leaving the floor strewn with loose stones and boulders, and the channels at the foot of the S. wall were much more deeply cut.

We next turned our attention to the new passage and very soon reached the point, since called the Stream Chamber, which terminated the exploration made in 1905. Hastings was left in the large stalactite chamber engaged in photography; Botterill, who was making a route survey, staying with him. l From the Stream Chamber, still following the same general direction (N.W.) We entered upon a series of chambers and passages in bewildering succession.

They contained the finest specimens of stalactite formation that Gaping Ghyll had yet permitted us to see, pure brilliant white in every variety of form; pendant groups at the intersection of the arches; broad, delicately tinted leaf forms; clustered columns, and stalagmites six inches in diameter rising in some cases to a height of 3and a half feet. In some places the walls were covered with an ice like film and a tracery of white veins; in others, the edges of the arches were outlined by a fringe of pure white.

The going now became somewhat difficult, our route leading through vertical fissures with wedged boulders between which it was necessary to wriggle. In such places one is apt to complain because all the joints in the human body are not on the ball-and-socket principle. Contending with these difficulties we proceeded until our way was apparently blocked by a fine fringe of stalactites which we did not wish to break through until it had, at least, been photographed. We were glad to find subsequently that the fringe could be passed without injury to the stalactites. One very remarkable tube stalactite at least three feet long was found here, so delicate that it vibrated in response to the air waves set in motion by our voices.

A shortage of candles made a speedy return to the Stream Chamber necessary; there we met the other two members of the party and enjoyed a genuine cave lunch. It was then conclusively demonstrated that all courses, including soup, could be disposed of without either etiquette or utensils with perfectly satisfactory results. We then returned to the main hole and the ladder was once more climbed to the surface.

The following day Fell Beck was again turned into the main hole and the windlass got into working order. Booth then descended the direct shaft for some distance below the point where the underground waterfall enters. He reported that although there was still a large quantity of water going down, this route was now quite feasible.

The fine dry weather had unfortunately come too late; a large number of our men could stay no longer, and amongst them were several of the surveyors and geologists of the party who had not had the opportunity of making the descent.

As we were unable to make an early start it was decided that the exploring party should stay down all night, and arrangements were made accordingly.

Provisions and other necessaries were taken on to the Stream Chamber, and everything prepared for the night’s work. A party consisting of Booth, Parsons, Slingsby and Hastings (who undertook the photographic work) started and made a more detailed examination of the passages traversed on the previous day. They reached a point about 20 yards further than the stalactite fringe, where the passage came to an end (800 yards from the Hole). After spending some time in photography they returned to the Stream Chamber and followed the stream upwards for about half-an-hour, Parsons reaching the end after a very trying crawl through a vertical fissure which terminated in a belfry chamber about 60 feet high. Returning to the Stream Chamber, the water was followed for a short distance along its northern exit from the chamber, but it disappeared before long in the loose blocks forming the floor. Another way was also found leading back again into the Stream Chamber by way of the mud pot.

On again arriving at the “T” junction, the party started to explore the S.E. branch passage, about 120 yards along which they entered a large chamber having several exits; all were tried, and, excepting one leading S.E., came to an end within a short distance. This S.E. passage on being followed for about 60 yards entered another passage at right angles to it, the S.S.E. branch of which worked out to a dead end in 20 yards, whilst that to the N.N.W., about 40 yards long, terminated in a pothole. Climbing down it for about 50 feet a large ledge was reached, beyond which it was impossible to proceed without the aid of more tackle. The depth of the pot was estimated at 150 feet from the roof, or 100 feet from the ledge. At this point two other passages were noticed, but not explored.

Time flies in a very remarkable way during underground exploration. Few men care to expose their watches to the danger of mud and water, and guesses at the passing hours are often found later to have been very wide of the mark. The heavy man of the party had set his foot on the clock intended for use below ground and reduced it to a state of hopeless imbecility, so the night’s proceedings could not be very accurately timed.

On the surface a fire had been lighted near the windlass and Green and Robinson stayed up all night ready to answer by telephone any call from below. It was four o’clock before the expected message came from the explorers, who had thus spent a day and a night working in alternately cramped and rough rock-strewn passages. The men in camp were then turned out and the explorers raised to the surface.

Later in the day two ladies made the descent, and it was peculiarly fitting that this, the second descent of Gaping Ghyll by a lady, should be accomplished by Mrs. Alfred Barran, followed by Miss Slingsby, the one being the wife of the then President of the Club, and the other the daughter of its Ex-President. On the following day Miss Booth and Mrs. Boyes made the descent.

The ladies are to be congratulated on their courage in venturing upon what may be considered a distinctly formidable undertaking. There are few ladies who would care to be lowered on a rope down a 340 feet shaft in semi-darkness, to be suddenly submerged in an underground waterfall whilst spinning round in mid-air, suspended, according to an apt description, “like a spider hanging from the inside of the dome of a large cathedral,” and finally dropped into a pool of cold water amidst a mass of rounded boulders.

They made the circuit of the cavern and examined the entrance to the newly discovered passages before returning to the surface, having evidently enjoyed the novelty of their experiences.

The party was by now so far reduced in numbers that it was impossible to attempt any further exploration, and after some other members had availed themselves of the opportunity of making the descent we commenced the laborious work of bringing to the surface the remainder of the stores, the ladders and telephone, and not until 11 p.m. was the last man, Parsons at liberty to come up.

The night was still and dark; with strained attention ghostly figures stood at their posts awaiting Parsons’ signal, while the continuous, subdued roar of the Water as it fell into the chasm sounded in their ears. On such a night Gaping Ghyll has a personality and claims kinship with the mountains. One recognizes the presence of a restrained but gigantic natural force: in some measure as when standing outside a mountain hut one sees the morrow’s peak-a black form looming barely distinguishable against the sky, and feels, in the growing darkness, overpowered by its immensity.

It was with a feeling of regret that we had to bring the expedition to a close while so much remained to be done, but the weather conditions of the previous week had greatly hindered our work. The next two or three days were spent in packing and transporting tackle and camp equipment to Clapdale Farm.

The following is the list of those who made the descent :-

A. Barran and Mrs. Barran, W. Cecil Slingsby and Miss Slingsby, Miss Booth, Mrs. Boyes, T. S. Booth, F. Botterill, H. Buckley, R. A. Chadwick, S. W. Cuttriss, C. Hastings, A. E. Horn, F. Horsell, G. L. Hudson, W. Parsons, W. Puttrell, P. Robinson, W. Simpson, and H. Williamson.

For the convenience of the expedition, C. Scriven kindly lent tents and other necessaries of camping and also had charge of the well arranged commissariat, while some other members brought their own tents. Thanks are due to: A. Green who had charge on the surface for the whole time, and to other members who though not making the descent, rendered assistance, viz: H. Brodrick, F. Constantine, Dr.A. R. Dwerryhouse, C. A. Hill, F. Leach, G. T. Lowe, and Lewis Moore.