Sinai: A Desert Ride

By John J. Brigg.

After listening to my recent paper with the above title some of my fellow Ramblers were pleased to say that I had made a very good tale out of a desert. I fancy they had the common idea that every desert is a vast unbroken level stretch of golden sand, without a hillock or a tree, and, certainly, the best-known history of the Desert of Sinai speaks only of one mountain. Elijah Walton’s wonderful pen and ink panorama of the Sinai Peaks in the Cambridge University Library, however, is sufficient proof to the contrary. Sinai indeed, as Dean Stanley has said, combines the landscape beauties of the desert, the mountains and the sea; no part of it is very far from the sea and none of its plains are “out of sight of land” – there is always some higher ground in view.

Of our trip from Suez to Mount Sinai and back, made in the spring of 1912, let me give an impressionist picture. As we tried to travel in comfort we had tents and camp beds and men to cook, wait and pack up tents and look after our transport. Every evening, therefore, saw five tents pitched and a table spread, and every noon some score of baggage camels striding along ahead whilst we spent a long siesta, sheltered from the blazing sun, in a comfortable tent. As the Peninsula of Sinai is under the Government of the Soudan I need not say there was no fear of man; and the cheerful rabble of Arab camel-drivers who accompanied us were as happy and helpful an escort as any traveller could wish, carrying indeed, for ‘pomp and circumstance,’ a few scimitars and guns, but much more at home with the long stone-headed pipes which they passed from hand to hand as they walked alongside, yarning all the time in resounding Arabic. It was no hardship to get up at 4.30 a.m., knowing that we should thus secure a few hours of the cool and exhilarating desert air before the torrid breath of mid- day, and there was always something to interest the rider who looked beyond his camel’s head-stall. Even in the first three days’ march, that ‘three days’ journey in the wilderness,’ where, as of old, one ‘finds no water,’ there were a few birds, or perhaps a huge green lizard running between the camel’s feet, and in the distance the lagoons and land locked lakes of the Mirage and glimpses of the sapphire sea, with a ‘tramp’ or a ‘liner’ to take one’s thoughts back to the busy harbours of England.

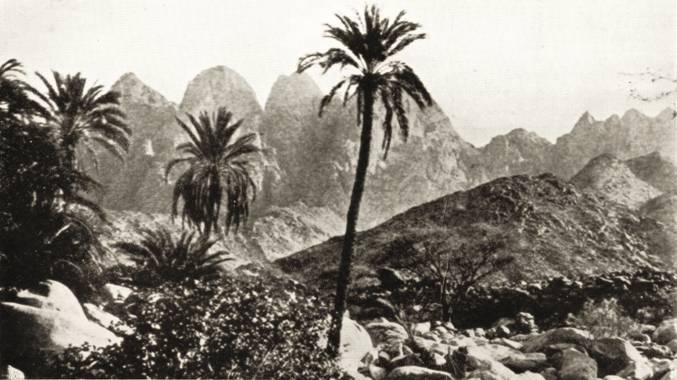

We halted at the time-honoured watering-places which alone make the desert highway possible, the hills increasing in height as we fared southwards, and one camp especially on the Red Sea beach, strewn with wrecks of coral and tropic shells, between two headlands, will always be a pleasant memory. Striking inland through the various ‘Wadys’ or narrow valleys that wind between the barren hills, we left the limestone region of the North and came to the hills of Red Sandstone where the ancient Kings of Egypt quarried for turquoise five thousand years ago and left their names and titles graven on the rocks. Later travellers – fifteen centuries ago – have scribbled their names in inscriptions which, for long, were attributed to the Israelites. The hard gravelly surface of these valley floors afforded very good going and some of us found the first two hours, in the bright morning air, a pleasant preparation for the day’s voyage on a swaying camel. Passing the sandstone hills we came to the true mountains of Sinai – peaks of granite, grey or red, their rocky ribs bare of any kind of soil or vegetation, with great veins of intrusive rock, porphyry diorite and greenstone, seaming their flanks for miles. Rain does fall sometimes and the water which comes to the surface, here and there, forms fertile “oases,” of which the Oasis of Feirán – “The Pearl of the Desert” – the scene of Moses’ great battle with Amalek, is the most famous. After days of hard, dry desert, it came as a shock to splash into a running stream and find the tents pitched by a grove of palms with reeds, fruit-trees and patches of corn. Here, also, we found our first mountain – Jebel Serbal (6,500 ft.), not of great height, but a shapely peak, reminding one of the Mickledore side of Scafell, with five domed peaks and deep gullies between. Our climb – for I need hardly say we climbed it – was a pleasant day’s outing. Camels took us to where the path ended and the ascent was up a long and laborious gully of rocks. Our guide, who might have sat for ‘Phra the Phonician,’ went up like a cat, with all our belongings slung over his shoulders in a white sheet, and a rope which Baedeker’s quite unnecessary caution had induced us to bring with us. Sweet smelling herbs fill the crevices nearly to the summit, which Dean Stanley aptly likens to a gigantic turtle. We saw all the land before us like a relief map, with the Red Sea and the mountains of Egypt beyond. Altogether, Jebel Serbál, “The Peak of the Coat of Mail,” – an apt Arab simile from its smooth granite summit – remains in one’s mind a pleasant memory.

As we left the Oasis of Feirán our camels had the unusual experience of wading knee deep in a clear running stream, but we were soon again in the ‘great and terrible wilderness,’ and nearing the central knot of mountains. Our luck in the weather still held, clear skies and a brisk north wind to temper the sun’s heat. The trees in Sinai are few but hardy and generally dry and spiky. The aromatic shrubs are many and varied, and judging from his breath, the camel likes a pot pourri of them all for his wayside snacks.

After this we climbed a rather long and rugged track – the Pass of the Winds – up into the hills, and came out on to the plain dominated by the Mount Sinai – Jebel Musa and his brethren, Ras es Sufsafeh and the rest. Close under the granite crags of Jebel Musa is the fortified monastery of St. Catharine, an outpost of Christianity in the Arabian desert. Here we spent several days as restfully as a ‘Rambler’ can, that is to say, we, or some of us, climbed three peaks on the three days we were there and rested nearly a whole afternoon. Our tents were pitched in the pleasant gardens of the monastery, under a row of gigantic cypresses, and behind us and in front towered the granite crags which glowed warm in the evening sunlight ere the stars came out to peep at us through the cypress leaves. The Monastery Church is a marvel of barbaric beauty, with its mosaics, pictures, gold and silver ornaments, and forest of hanging lamps, while the shields of arms rudely scratched, perhaps by Crusaders, on the carved wooden doors of the porch, lend a touch of human nature. More than once did we attend the monks’ service and try to apprehend their scheme of music, and some of us visited the ancient bone-house, where a skeleton porter has sat as doorkeeper for a thousand years. The famous library where Tischendorff found his Greek MSS. of the New Testament and rescued leaves of other precious volumes from the furnace is now cleaned up and as spick and span as a Carnegie library. Any reference to the Codex Sinaiticus, which their predecessors esteemed so lightly, is now considered by the Prior and his monks in rather bad taste. Jebel Musa, the Holy Mountain of Sinai, is climbed by a well engineered pilgrim-way and so can hardly rank as an ascent, but we did have a little scrambling among the summits of Ras es Sufsafeh – in fact we were stopped by a steep little chimney below its summit, which, Stanley says, judiciously, “ought to be climbed for the view.” The neighbouring peak, Jebel Kathrein (8,550 ft.), the highest in the Peninsula, has a well-made road nearly as far as to the chapel and little refuge on the summit. Our guide was an intelligent monk who had kept school in some far-off island in the Ægean, and we had the unusual experience of discussing the pronunciation of Greek in a Greek chapel, 8,550 ft. above the sea. The downward road passes a spring called “The Well of the Partridges,” because it sprang up to refresh the partridges which had accompanied the body of the martyred Catharine as it was borne by angels from Alexandria to Jebel Kathrein.

We left the Monastery of Sinai with regret and made our way back to the coast. Perhaps the most impressive part of the trip came at the end where, through a long and narrow defile twenty feet wide and a thousand feet above our heads, we suddenly emerged into the desert sloping down to the sea. This, the desert of Kaa or Gaa, is more like the absolutely stony waste of our ideas than anything else we saw. We had a brisk morning’s ride across it and came at last to a little port called Tor, chiefly remarkable as being the place of quarantine for the pilgrims returning from Mecca to Egypt. There are ‘compounds’ which will accommodate 50,000 at once, but we found them ‘out of season’ and empty, and in charge of a plucky Englishman – though I think his wife better deserves the epithet – stuck out there alone.

The last we saw of our faithful Arabs – by this time there were about fifty of them – was a gesticulating crowd on the little pier as we put off to the Khedivial Line SS. Neghileh that brought us back to Suez and civilization.