Clapham Cave

By The Late Charles A. Hill.

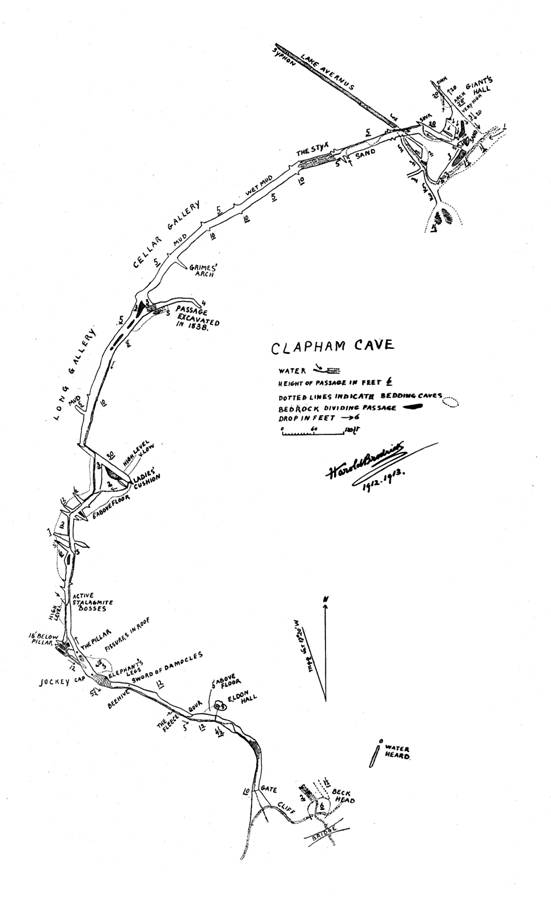

Introductory. Clapham Cave, or as it is sometimes called Ingleborough Cave, has been known for so many years that it would seem there was little new to be written about it. Yet there is still something fresh to be said. For instance, the history of its early exploration, though extant in MSS., has never been printed nor published, and its Plan (though produced in 1838, the year following its discovery) is known or accessible to but few. Admirable as this Plan is, it does not include the whole length of the Cave; the whole of the area beyond the point known as “Giant’s Hall” being marked as “unexplored.” This region is seldom visited owing to its remoteness and inaccessibility, as it is possible only in times of prolonged drought to descend to its usually water-logged passages and to traverse its low and exceedingly uncomfortable galleries.

The work here detailed was undertaken during the summers of 1912 and 1913 with the view of filling in the unsurveyed portions of the existing Plan and clearing up several doubtful points which, in the opinion of the writer, required elucidation.

As already stated, the existing Plan of Clapham Cave was drawn from a survey made in 1838, the year following its discovery. This Plan, however, does not go further than the point known as “Giant’s Hall,” and as there is an area extending some distance beyond at a lower level, it was determined to survey this section, and at the same time to check the existing Plan by a resurvey of the passages and chambers already mapped, thus completing the Plan of the entire cave.

This new survey was partially carried out during the summer of 1912. During that year, however, it was found impossible to carry it beyond “Giant’s Hall” owing to the formation of an impassable choke of sand on the slope giving access to this low-level area. This choke, which seems to have formed within recent years, proved to be only temporary in character, and had disappeared by the summer of 1913, when the new survey was completed without difficulty.

The work of the survey was carried out by the writer, assisted by the valuable co-operation of Mr. Harold Brodrick, and the latter is responsible for the Plan. Various members of the Club have from time to time joined in the exploration, to all of whom my best thanks are due.

I am also greatly indebted to Mr. Claude Barton, the agent for the Ingleborough Estate, who has placed every facility in my way for carrying out the work.

I should like to place on record an appreciation of the careful and accurate manner in which the first survey was made and of the correctness of its details.

Whilst engaged on the work of the survey I was enabled, through the courtesy of Mr. J. A. Farrer, the owner of the Cave, to inspect the “Cave Book,”[1] a MS. Journal written by his grandfather during the years 1838-53, which contains a description of the Cave as first discovered. This book furnishes so many facts of historical interest in connection with the discovery and early exploration of the Cave (facts hitherto unpublished and therefore generally unknown), that I propose to draw largely on the fund of information which it contains, and to quote from it at length where necessary.

Record Of The First Exploration. – The Cave, at the time the first attack was made upon it, seems to have been penetrable for a distance of 56½ yds., at which point there was a thick barrier of stalagmite called “The Bay,” holding up a deep pool of water to within a few inches of the flat roof from which stalactites depended to the surface of the water. The old level of this pool is still visible on the walls.

The first entry in the Cave Book reads as follows:-

“On the 16th September, 1837, heavy rain swelled the beck so as to cause one of the heaviest floods ever known. The water rushed out not only from the Cave and Beck Head, but also from the side of the hill on the left-hand about 20 yds. above Beck Head. On the 22nd I went up with Jo to consider of the possibility of opening a passage into this part of the hill. The sound of rushing water was very distinct, and induced us to expect to find an entrance into some large cavern. Two men were set to work to remove the stones that filled up the hollow by the rock side.

The experiment not succeeding, Jo, on the 23rd, took the men into the old cave to the extremity of it, which was called ‘The Bay,’ and there broke a passage through the stalagmite that formed it. This opened to the New Caves – first into that small part which is now called ‘The Porch,’ and thence to ‘The First Basin.’ John Gornie and Robert Bradley waded through this Basin and thence through ‘The Second Basin’ to a point 76 yds. from the gate of the Cave. In the afternoon of the 23rd Encombe and Matt. reached the same distance.”

“Jo” was Josiah Harrison, an old and valued servant of the Farrers, and the grandfather of the present guide to the Cave. There can be little doubt that the discovery of the New Cave was due to his initiative. “Encombe” was Viscount Encombe, afterwards John, second Earl of Eldon; There is a note in his handwriting affixed in the Cave Book which epitomizes the progress of the subsequent explorations in a few words. It will be noted from this that the distance of 76 yds. given above as the limit of the first day’s exploration is not quite correct. It should have been 85 yds., an error which is rectified by Mr. Farrer in his succeeding entry in the Cave Book. Lord Encombe’s note reads as follows:-

“On September 23rd, 1837, the New Cave was broken through by three labourers under Jo Harrison, two of whom penetrated to the point at 85 yds. from the Entrance Gate, which M.T.F and Encombe reached later in the same day, breast high in water at that time.

On September 26th, James, Matt., Thomas, Henry, &c., reached ‘The Pillar,’ and in a second exploring on the same day they penetrated to the point blocked up by stalactited pebbles at (supposed) 450 yds. from the Entrance Gate.

On September 29th, James, Matt. and Henry remained at a spot (supposed) about 790 yds., …ing a very shallow descent, while two labourers proceeded to the deep water reached on October 11th.

October 11th, 1837, James, M.T.F. and Encombe, accompanied by Wm. Hindley, passed through the shallow waterfall and reached the deep water at the distance (supposed) of 940 yds. from the Entrance Gate. (Here James swam with a rope attached.)

N.B. – The distances are given not entirely at random guesses, but by the length of balls of twine, used as guides for returning.”

This record shows that on the second day the explorers reached the end of the present tourist part of the Cave, i.e., just before the commencement of the Cellar Gallery, and that on the third and fourth days they penetrated the full length of the Cave as at present known, getting through the low passages beyond Giant’s Hall as far as the river, and traversing the straight “canal” which they named “Lake Avernus.”[2]

Thus within three weeks of its being opened out practically the whole extent of the New Cave was known, with the exception of Giant’s Hall, whose existence at that time was unsuspected, and to whose discovery I shall refer later.

Returning for a moment to the point where the exploration ceased on the second day (September 26th), “the point blocked up by stalactited pebbles at (supposed) 450 yds. from the Entrance Gate.” This is clearly the blind passage just beyond the end of the present tourist part of the Cave, a passage which shows signs of having been at some period artificially excavated.

There is a letter preserved in the Cave Book which throws light on this matter. Dated April 23rd, 1838, and written by Mr. James Farrar to his father, it reads as follows; –

“We have been working this afternoon in the Cave, endeavouring to find a passage from one of the transverse arches in the Cellar-arched part of the Cave communicating with the supposed continuation of that part which is blocked up with sand and stones about 200 yds. beyond the creeping part ….. We have little doubt of being able to clear the passage, having already disentombed several stalactites. The discovery of limestone gravel is also very remarkable, with thick strata of clay above it. Should we at any time work through this we may reasonably expect to find remains of bones, &c. The solid and compact form of the strata very much strengthens one’s belief in its antiquity.”

Evidently the attempt was abandoned after excavating a short distance, as the passage was found to turn away from the Cellar Gallery, and to be devoid of remains of bones, &c. It will be seen from the Plan that the trend of this passage is towards the valley and not into the hill in the direction of Gaping Ghyll, so that further excavation would probably not have led to any discovery of interest.

Giant’S Hall. – This would seem to have escaped detection during the first explorations of the Cave in 1837, and to have been discovered as the result of the investigations carried on by Mr. James Farrer during the year 1838.

The records of the year 1837 make no mention whatever of the Hall. In Mr. James Farrer’s “Further Description” we read a detailed account of the passages traversed by the first explorers on their way to the “River.” Passing along the Cellar Gallery, “nothing particular occurs till the long Gothic Arch is reached. This part of the Cave is rather narrower and is most beautifully inlaid with stalactite of different forms and sizes; and finally, after about 30 or 40 yds., terminates in a low narrow point, where the arch has evidently been blocked up by stones and sand and accumulated stalagmite. The passage, which turns to the left, now becomes very narrow, and the descent very sudden. On reaching the bottom . . . &c.”

Evidently the entrance to the Hall was so masked by the accumulation of stones and sand as at that time to be unrecognizable. So much for the year 1837.

In the entry dated 26th October, 1845, we find a record of the progress made during the following year, 1838, from which we learn of the discovery of the Giant’s Hall, or as it was first called “The Baron’s Hall,” and of a survey of the Cave being made by a Mr. Hodgson, from which the existing Plan was drawn.

This entry reads as follows: –

“Since I made the former notes of this very interesting series of the hidden operations of nature, further discoveries have been made under the personal direction of James Farrer. The last cavern which he reached is called ‘The Baron’s Hall.’ In the autumn of the year 1838 we had a regular survey made of the whole by Mr. Hodgson, from which he drew the plan now in our possession. Upon his plan are noted the names of the different objects which were given by the discoverers.”

Since Giant’s Hall is figured on Hodgson’s Plan, it must evidently have been discovered during the earlier part of 1838.

The description of the Hall from this entry of 1845 reads as follows: –

“The entrance into the Baron’s Hall is low, the rock impending towards the sandy bottom so as to drive you to crawl or stoop very low. On the right hand as you enter at a considerable height is an opening and projecting mass of breccia covered with stalagmite, through which it appears that formerly the stream was projected.”

This opening is at a height of 20 feet above the floor; although spacious it soon closes in, being blocked by an impenetrable mass of breccia composed of rounded water-worn pebbles and clay, covered with stalagmite.

There is also upon the MS. Plan an entry which is of great interest and as throwing a possible light on the discovery of Giant’s Hall. At the end of the “Gothic Gallery” occur the words “New Passage opened by Flood in 1838. Very low and unexplored.” In the previous year this spot was described as “A low, narrow point where the arch has evidently been blocked up by stones and sand and accumulated stalagmite.” And in the account of 1845, mentioned above, “The rush of waters is loud at the end of the Gothic Arch.” Evidently the flood of 1838 wrought a great change here, and it is possible may have opened up the entrance to Giant’s Hall by altering the disposition of the sand.

The “low, narrow point” where the arch has evidently been blocked up by stones and sand and accumulated stalagmite,” and where “the rush of waters is loud at the end of the Gothic Arch” is marked on Hodgson’s Plan by the word “column.” This formation is a very noticeable feature at the end of the Gothic Arch and has been used in the new survey of the Cave. The “rush of waters” is at the present time still very “loud at the end of the Gothic Arch.” An attempt was made during the survey of 1912 to penetrate beyond this point, but the pool of still cold water on the far side of the column, coupled with the lowness of the roof, proved an insuperable obstacle to any exploration in this direction.

In 1913, however, during the survey of the low level area a spot was reached where the relationship between the open end of the Gothic Arch and the area below proved easy of solution. On measurement the distance between these two points proved to be 12 ft. vertically.

There is thus evidence that great activity was displayed during the year 1838. It marks the discovery of Giant’s Hall and the survey of the Cave by Mr. Hodgson, from which all of the existing Plans have since been drawn. There is also on record that an attempt was made to ascertain the length of Lake Avernus by sending a floating light along it. The plan in the Cave Book, which is reproduced in this Journal (vol. II., p. 60), has the following note affixed to the end of Lake Avernus :- “The floating light arrived at a supposed distance of 891 yds. from Cave Entrance.” As the beginning of the Lake is labelled as 811 yds., this would make out its total length as 80 yds. As a matter of fact this conjecture slightly under-estimates the reality. The exploration of 1896, to which I shall presently refer, proved the total length to be something over 100 yds., a figure which can be accepted as accurate.

It was in the October of this same year that Prof. Adam Sedgwick, the famous Woodwardian Professor of Geology at the University of Cambridge, whilst staying in the neighbourhood, visited the Cave and accompanied an exploring party to the low-level area beyond Giant’s Hall.

An account of this exploration is to be read in his Life (vol. I., p. 519), where, in a letter to the Rev. W. Ainger, he details the various incidents that took place on that occasion. The passage descriptive of this is quoted at length in Mr. Geo. H. Brown’s pamphlet[3] and excerpts are also given in this Journal (vol. II., p. 61).

The net result was that the explorers “were satisfied that no other caves are within reach on that side,” a conclusion which still holds good at the present time. This assertion seems naturally to have choked off all further exploration for the time being; and beyond the measurement of certain well-known stalactites, such as “The Jockey Cap” and others which cannot now be identified, nothing further of note appears until the year 1872.

During this year a party, which included Prof. T. McKenny Hughes, Mr. John Birkbeck (of Settle), and the Rev. G. Style (then Headmaster of Giggleswick) and others, visited the low-level area beyond Giant’s Hall, prompted doubtless by the hope that the celebrated flood of that year would have wrought great changes in the interior of the Cave. (See Mr. Style’s letter in Y.R.C. Journal, vol. II., p. 32.) [Web Note: This reference is incorrect & actually refers to p. 52.]

But, with the exception of the Cellar Gallery, practically no alterations were found and no new ground was broken. Previous to the flood the Cellar Gallery was practicable even for ladies. (See Sedgwick’s account of his visit when a party which included ladies lunched in Giant’s Hall.) Since that time the changes wrought by the flood have necessitated wading through the three feet of water held up by a barrier of sand across the far end of the gallery.

Prof Hughes published a most interesting account of the great flood of 1872 in a paper read before the Victoria Institute, or Philosophical Society of Great Britain, in 1887. As he there states, he “had the good fortune to witness one of those grand storms which in a few minutes change the face of nature and in a few hours leave a mark that ages may not efface.” His description of the condition of the Cave after the tremendous rainfall caused by the storm is well worthy of reproduction. “I went,” he says, “up the valley round the Lake towards the celebrated Ingleborough Cave. It was a striking scene. Water spurted out of every crack and joint in the rocks, but the united subterranean watercourses could not carry it all, and the overflow from the drift-covered country above the usual outfalls rushed down the valley, carrying mud and boulders with it in its headlong course. The stream below the Cave runs over bare limestone for a considerable distance, and the noise made by the boulders, as they were rolled along the rocky floor, was so great that my companions thought the thunderstorm was beginning again and hurried home. I went on to the great cave. Here I saw a wonderful sight. The lower cave was full, and the water was spouting out of the upper cave, which is usually dry, as you pour water out of the mouth of a kettle; and well it might, for, if the swallow-hole that feeds it was full to overflowing it had had the pressure of more than eleven atmospheres upon it. This was one of the most instructive phenomena it has ever fallen to my lot to witness.”

After such a “local cataclysm” it is scarcely to be wondered at that fresh exploration was undertaken, with the result, however, as has been stated above.

Nothing further seems to have been undertaken until the year 1896, when a party of Yorkshire Ramblers went down to the low-level area beyond Giant’s Hall and traversed Lake Avernus by means of a raft, measuring its length and sounding its depth. An account of this exploration is to be found in this Journal (vol. I., pp. 220-228). This account was written under the impression that the party was breaking new ground, but the publication of the article speedily called forth a correction, which will be found in No. 5 of the Journal, in a series of letters; all are of great value and historic interest.

In June, 1903, some members of the Club, including myself, visited the low-level area but discovered nothing new.

The summer of 1905 was remarkable for a prolonged drought, during which many of the active water channels and sinks on Ingleborough completely dried up, notably Mere Gill, where the waterfall entirely disappeared and the lake at the bottom of the chasm sank to small dimensions. These extraordinary conditions suggested to a party of the Club members who were then engaged in exploring this particular pot-hole that a more favourable opportunity could not be found for an attack on the low level area of Clapham Cave, with a view of connecting it with the passages of Gaping Ghyll, which by this time had been descended and explored for a long way in the direction of the Cave, and a determined attempt was accordingly made to solve this problem. In this connection I ought to state here that previous explorations had always tended to follow the downward course of the running water towards its exit rather than upwards towards its entrance into this area. On this occasion the exploration was pursued upwards. A low bedding cave out of which the stream pours was found to be half full. Up this the explorers pushed for a considerable distance until, with their bodies wholly submerged and their mouths half under water, they decided it was best to retreat. In front of them still stretched a tunnel which looked capable of passage had the conditions been a little more favourable. But prolonged immersion in cold water can be borne only for a short period even by the hardiest of men, so Nature conquered and the Cave still holds its secret.

On this occasion much new ground was traversed, but it was under exceptional circumstances such as are unlikely to occur again, and therefore we may take it as certain that the limit of exploration has been reached as regards the upward extension of the Cave. As to the lower extension the same may be said to apply because the area which concentrates on the end of Lake Avernus is certainly closed by a syphon.

Until this lower extension was surveyed by compass and measuring tape in 1913 its direction had always been taken as pointing towards Beck Head (see the Map in Y.R.C. Journal, Vol. I., p. 130) But the infallible compass has shown that Lake Avernus instead of trending in the direction that previous explorers have always thought it to go, i.e., parallel with the glen and so running towards Beck Head, really takes quite a different course. The Survey of 1913 demonstrates that the commencement of Lake Avernus lies directly beneath the last transverse arch in the Cellar Gallery and that the Lake runs in a N.W. direction straight back into the heart of the mountain in a direction almost parallel with Trow Ghyll.

This Survey of 1913 has also demonstrated the relationship between the water-sink at the end of the Cellar Gallery (see Plan in Y.R.C. Journal, vol. II., p. 56) and Lake Avernus (see Plan on p. 60). In this latter plan will be noted a point marked “X, waterfall heard,” just at the commencement of Lake Avernus. These two points ought to be superimposed. There is a difference in level of only about 12 ft. The result is that when the Low Level Area floods to its utmost capacity, which it does even after a moderate rainfall, owing to the exit at the end of Lake Avernus being a syphon, the water rises up through this sinkhole and this regurgitation is spread over the end of the Cellar Gallery and the Gothic Arch, thus tending to alter constantly the disposition of the sand which is here piled up in large quantities. This explains why this part of the Cave is constantly altering in appearance; a fact I have verified from my own personal experience during the summer of 1912.

Attempts have been made on several occasions to find an exit from Giant’s Hall on a high level. The height of the chamber is at least 60 ft., and there are various openings at different levels to be seen by means of the search light, all of which, however, on examination have proved to be impracticable. Only one of them needs to be described in detail. As you enter the Hall there is on the left hand side an overhanging shelf some 15 ft. high. This was surmounted by means of a wooden ladder, and, after climbing up a steep slope covered with slippery stalagmite, a narrow ledge was reached about 27 ft. above the floor. On this ledge there was just room to fix a second wooden ladder by whose aid an opening 10 ft. higher was reached, which seemed promising. This opening was partially blocked with wet clay and a certain amount of excavation was undertaken, but the labour under such conditions being dangerous and the reward scanty, the attempt was abandoned.

The Sand. – The most striking feature of the Cave in the region of Giant’s Hall is the presence of large quantities of sand piled up at the end of the Cellar Gallery, in the Gothic Arch, in the Hall itself and covering the slopes leading down to the Low Level Area. All this region is constantly being flooded by the water rising up from the Low Level Area and every flood alters the disposition of the sand, but is always tending to wash it down to a lower level. Even my own observations, extending over a limited number of years, have evinced to me how great is the alteration that is taking place. In 1903 it was hard to find the entrance to the Hall, and when found it was difficult of access. Now the approach is easy and obvious. The same applies to the exit towards the Low Level Area. We read that the condition in 1896 was as follows: – “A slit some 6 in. high running along the base of the side to the right of where we had entered. The roof of the slit was rock, below was sand. Through this we commenced to burrow.”[4] Now it is totally different, the first 20 ft. of the descent being down a slope of bed-rock absolutely bare of sand.

Even the end of the Cellar Gallery has been found to alter greatly in a month’s interval, the mounds of sand having quite a different shape and disposition, while footmarks were totally obliterated.

The original point of disposition of the sand would appear to have been in Giant’s Hall, and the water there has since been constantly at work removing it to a lower level. That being so, the question naturally arises how came it there and by what channels has it reached this chamber since the time that its parent (the Millstone Grit) was disintegrated on the upper slopes of Ingleborough and washed down Gaping Ghyll and other openings? One would expect from the enormous quantities present to find some large orifice either in the sides or roof of the Hall through which this detritus could pass. A careful search, however, by powerful illumination has revealed nothing which one can definitely recognize at the present time as being the channel. The search light has disclosed several openings high up in the chamber, but on closer inspection each of these has proved impracticable. The most active of these openings appeared to be one above the 27 ft. ledge, but this also has been found on examination to be impracticable. Judging by the moist condition of the mud that covers this ledge and by the fact that the sand on the floor immediately underneath is often deeply furrowed and cut into a miniature watercourse, it is easy to see that in wet weather water must descend from some point above in a considerable volume to carve such a channel. At the present time, however, this water brings down no sand in its fall; its action is merely to clear away and wash down to a lower level that sand which has formerly been deposited.

The conclusion to which one is forced from an inspection of Giant’s Hall at the present time is, that wherever and whatever the opening at the roof or sides of the Hall is through which sand formerly came, that opening has now ceased to be patent and has become sealed up by stalagmite. Sand is no longer carried into Giant’s Hall; that which has been deposited in the past is now being gradually washed down to a lower level than the floor of the Hall and so dispersed.

The Abyss, &C. – Reference may now be made to one or two points in the tourist part of the Cave which are marked on Hodgson’s Plan as “unsurveyed.” Chief of these, “The Abyss,” is that well-known opening in the floor of Pillar Hall into which sinks the stream running through the major portion of the Cave. Under ordinary conditions there is sufficient water engulphed here to make a descent for exploration and an accurate survey impracticable; whilst after very heavy rainfall it is on record that the chasm has completely filled up so that the water has almost reached the foot of the Pillar. Favoured, however, by the prolonged drought of the summer of 1912, I was able to make a thorough examination of the passages draining the Abyss. These proved disappointing so far as exploration was concerned, being merely fissures too narrow to traverse for any distance. The compass, however, showed that their direction, if prolonged far enough, would terminate at Beck Head, thus confirming the conclusion arrived at by the Committee on the Underground Waters of N.W. Yorkshire, in 1900, as to the direct connection between these two points. The annexed Plan illustrates how this occurs.

The line of this connection may clearly be seen as a well marked fissure running diagonally across the roof of Pillar Hall, directly over the Pillar itself, a fact which has certainly been in the past the determining cause of the formation of this fine and interesting column.

The next “unsurveyed” point to which I shall refer is one in the First Gothic Arch – that welcome place of relief which the tourist reaches after traversing that part of the Cave which the first explorers called “the first creeping place,” and which is yet, even after modern improvements, a trial for those of average stature. In the First Gothic Arch as you face The Ladies’ Cushion – that well-known series of fine stalagmited terraces – there is, about 10 ft. up the left hand wall, a broad ledge giving access to a low wide bedding cave. This cave may be followed for about 60 ft., at which point it becomes too low to admit of further exploration, although the search light shows that it still continues onwards for some distance.

Besides these two points, all the others marked on Hodgson’s Plan as “unsurveyed” were examined in turn and all were found to be impracticable, thus verifying the conclusion Martel arrived at in 1896.[5]

The Jockey Cap. – Much has been written in the past about this beautiful and celebrated stalagmite, and varying theories as to its age have been evolved from the measured rate of its growth over a number of years. Thus, from 1839, when it was first measured, up to 1873, it presented an almost uniform rate of growth of ![]() in. annually, so that its age seemed easy of calculation. But subsequent observations have shown that its growth is not by any means so continuous as appeared at first sight. For the last forty years the rate of increase in size of the Jockey Cap has been gradually diminishing until during the last ten years it has become nil.

in. annually, so that its age seemed easy of calculation. But subsequent observations have shown that its growth is not by any means so continuous as appeared at first sight. For the last forty years the rate of increase in size of the Jockey Cap has been gradually diminishing until during the last ten years it has become nil.

This diminution may be due to two causes. The first, which is purely theoretical and for which there is no positive evidence, is that the dripping water feeding it contains less carbonate of lime than formerly. The second, which is a matter of actual observation by Mr. Harrison, the guide to the Cave, is that the quantity of water dripping from the point overhead is gradually year by year diminishing in amount. In other words, the funnel through which the water percolates is slowly becoming choked and will before many years cease to be patent.

There is corroborative evidence bearing on this from another source. When the Jockey Cap was first discovered there was a stalactite above it from which drops fell. In October, 1845, this stalactite was measured and proved to be 10 in. in length. The Cave Book records that in 1853, whilst taking a measurement, this stalactite was accidentally broken off. Its length was then 14 ¼ in., so that it had grown 4¼ in. in eight years. In other words it was not only a rapid but a recent growth as compared with the large mass of stalagmite beneath. Since then, i.e., during a period of sixty years, practically no new growth has taken place.

It would seem, therefore, that the history of the formation of the Jockey Cap has been something of this nature. At first, water heavily charged with carbonate of lime dripped so freely as to form stalagmite only, then the funnel through which it fell became choked so quickly that stalactite was formed with great rapidity. After the destruction of the stalactite, no fresh formation but the gradual obliteration of the funnel as shewn during the last two years by a total cessation of drip for weeks at a time. However, be the cause what it may, this much is certain from recent observations. (1) The drip of water is diminishing, and (2) the Jockey Cap is consequently no longer increasing in size, so far as can be judged by measurement.

In addition to the measurements of the jockey Cap the Cave Book gives others of a number of stalactites which I have been unable to identify with any precision. The description of their location is more or less vague, and though I have endeavoured to place them no value could, be assigned to such a problematical estimate of their rate of growth.

The Drainage System Of The Cave. – Every one who has visited the Cave must have, of necessity, noticed the large quantity of water flowing through it. But so far as I am aware no reference has ever been made to its drainage system.

As far as Pillar Hall all the water met with runs towards the Cave mouth, where it finds an exit. On surmounting the plateau on which the Pillar stands one is confronted with the Abyss, the bottom of which is 13 ft. below the foot of the Pillar. The Abyss is the most active and important water-sink in the Cave, and receives the whole of the drainage from this point to the end of the tourist portion, a distance of over 200 yds., the water here engulphed emerging at Beck Head. The watershed of the Cave is at the point called by the early explorers “The Second Creeping Place,” and is the sloping bank of bare limestone on the left of where the present-day tourist stops. It is about half way through the Cave and may justly be called “The Parting of the Waters.” In one direction the water runs towards the Abyss, in the other through the Cellar Gallery into the sink at its far end, where, as already explained, it falls into Lake Avernus.

Thus the drainage system of the Cave concentrates on these two openings. The Abyss, being the larger, will take more water, and in times of great flood is called upon to do so, because under such conditions the whole of the far end of the Cave becomes waterlogged, owing to the exit of Lake Avernus being a syphon, the Cellar Gallery fills up to the roof and the imprisoned waters then pour over the watershed and seek an exit through the Abyss.

In Hodgson’s Plan (1838) the level of the floor of the Cave from the iron gate at the entrance to as far as Giant’s Hall is plotted out in a diagram. This measurement has been checked by the recent survey and may be summarized thus. Taking the level of the gate as zero, there is a rise as far as the Pillar of 8 ft., thence onwards to the watershed a further rise of 5 ft., thus making the highest point on the floor of the Cave (i.e., the watershed) 13 ft. above the entrance gate. Along the Cellar Gallery there is a gradual decline of 10 ft., so that on reaching the water-sink at its ends the level of the floor is only 3 ft. above the entrance. The “column” at the end of the Gothic Arch is 3 ft. higher than the water-sink, i.e., 6 ft. above the entrance gate. Descending from Giant’s Hall the level of the stream bed, where first met, is 10 ft. below the column, but its floor gradually declines so that at the point where vocal communication is possible between these two points, the vertical distance is about 12 ft.

Attempts have been made from time to time to find a way into the Cave other than by the ordinary entrance. Beck Head for instance, which is an obvious place to try, speedily flattens out into a low bedding cave which is quite impassable. Then there is the spot on the left hand side of the glen about 20 yds. above Beck Head, where by listening at the foot of the cliff the noise of the underground river can be heard at two different points. This fact is recorded in the first entry in the Cave Book. “The water rushed out . . . . . . from the side of the hill on the left hand about 20 yds. above Beck Head. On the 22nd I went up with Jo to consider of the possibility of opening a passage into this part of the hill. The sound of rushing water was very distinct and induced us to expect to find an entrance into some large cavern. Two men were set to work to remove the stones that filled up the hollow by the rock side. The experiment not succeeding, &c., &c.” This was on the 22nd September, 1837.

Some seventy-four years later this experiment was repeated by some members of the Club, but again without success.

However, it must be remembered that on both these occasions no very serious attempt at excavation was made, and it is possible that a more thorough trial to find an access to the river might be successful, if it were thought worth while to undertake such work.

The recent excavations at Foxholes higher up the glen have demonstrated that this little valley is deeply choked with moraine and with rock weathered from its sides, and that its true rocky floor lies at some considerable depth below the present pathway. It is therefore possible that there exists an opening, now blocked with moraine, at a level as low as that of the exit at Beck Head.

There is another fact in reference to the Cave which has never to my knowledge been noted before, although the 6 in. O.S. Map gives an indication of it, i.e., that if you walk over the surface of the hill side under which the Cave is situate, you can see traced out on the ground by a series of continuous depressions the whole course of its subterranean ramifications. This can be observed even better by gaining the summit of a line of cliffs which abuts on this area. and by looking down from above. It is interesting to note in this connection that these surface indications cease at the depression marking the position of Giant’s Hall.

The Low Level Area Beyond Giant’S Hall. – As stated previously, Hodgson’s Plan leaves out all the area beyond Giant’s Hall, and no description of this part, which has now been surveyed for the first time, has ever been published. I propose therefore to describe briefly this portion of the Cave.

An inspection of the new Plan shows that two ways exist by which access may be gained to this Low Level Area. Of the two routes, that from Giant’s Hall is the easier, though neither can be truthfully described as easy. From the Hall there is a climb down a rock slope of 20 ft., then follows a squeeze between rock above and rock below which just[6] allows the ordinarily-sized mortal to slip through with discomfort and with much sand dispersed through his clothing. Ramblers of under-size have been heard to boast of the ease of this passage. A level floor, which is part of a huge bedding cave, is then reached through which runs a stream from left to right. As the space between the floor and roof is only 2 ft., the accommodation cannot be described as either spacious or luxurious. By keeping to the right a spot is soon reached where it is possible to stand upright. This is a circular chamber some 6 ft. in diameter, which is just beneath the column at the end of the Gothic Arch. From here one can talk to any one above, though the opening joining the two is too small to admit of actual passage.

Next ensues a return to the posture to which Scripture foretold the serpent should be cursed, and which afforded no comfort even to a member of the beneficed clergy who was of the survey party on this occasion. “Upon thy belly shall thou go,” and that “it shall bruise thy head,” were hard facts too patent to all. A crawl of 30 yds. along a stony stream bed, in a direction which the compass informed us was S.W., brought us again to the running water and to a place of higher dimensions where it was possible to sit in comparative comfort on a ledge of rock, and reflect on the truth of a text quoted quite à propos by the ecclesiastical explorer, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.” Luncheon time had now arrived.

Beyond here the best guide to direction is the downward course of the stream. Passages branch out in various directions, all of which have been followed as far as human endurance will permit, but without definite result. Following the stream onwards at a distance of 17 yds. a chamber is reached which stands at the entrance to Lake Avernus.

Here are ways in three obvious directions. Straight ahead under a fine arch some 3 ft. high the stream disappears, and falling in a series of cascades shortly enters the long straight canal known as “Lake Avernus.” On the right, when facing the arch, is a low tunnel which presently turns left at a right angle and affords an alternative route to the canal. The culvert on the left of the arch is promising, but soon becomes too narrow to follow.

The only record of a complete exploration of Lake Avernus is to be found in this Journal (vol. I., p. 226). The first exploration was attempted in 1838, when a floating light was sent along and the length was thereby conjectured. The exploration of 1896, to which reference has already been made, succeeded not only in measuring its true length but also in making various soundings in the endeavour to discover a likely outlet. On this occasion a raft was used, which is the only possible means of traversing a waterway too deep to wade and too narrow to swim in safety.

At that time its true direction was unknown, but as the compass has since demonstrated that a direct outlet of the waters towards Beck Head is quite impossible, the problem of their intermediate course is still unsettled.

Bibliography. – The first published description of the Cave is to be found in the Quarterly Journal, Geological Society, vol. V., 1849, pp 49-51, from the pen of Mr. James Farrer. This description is illustrated by a map taken from Hodgson’s Survey on a reduced scale.

Prof. Phillips, in his “Rivers, Mountains and Sea Coast of Yorkshire,” 1853, pp. 30-31, gives an interesting account of the interior of the Cave, which is quoted at length by Prof Boyd Dawkins in “Cave Hunting,” 1874, pp. 36-38.

Other references to the Cave are to be found in W. S. Banks’ “Walks in Yorkshire, N.W. and NE.” and in R. R. and M. Balderston’s “Ingleton: Bygone and Present,” pp. 55-59.

[3] There is also an excellent little pamphlet by Mr. Geo. H. Brown, published in 1905 by Lambert, of Settle (price 2d.), entitled “The Clapham Cave,” which contains a concise history of the Cave and a number of fine illustrations.

Mr. Harry Speight, in the “Craven Highlands,” also has a reference to the Cave.

M. Martel, that indefatigable French speleologist, in his memoir entitled “Irlande et Cavernes Anglaises,” devotes nearly the whole of Chap. 4III. to this subject.

The “Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society,” of April, 1873, contain a paper by Prof. Boyd Dawkins on the estimated growth of the “Jockey Cap” to that time.

Length Of The Cave.

The following figures taken from the recent survey will be of interest:-

| From the Entrance Gate to the end of the Tourist part (i.e., to the Watershed) is | . . . | 418 yards. |

| From here to the entrance to Giant’s Hall. | . . . | 279 yards. |

| From Giant’s Hall to the commencement of Lake Avernus | . . . | 99 yards. |

| The estimated length of Lake Avernus is, say’s Hall to the commencement of Lake Avernus | . . . | 104 yards. |

Making the total length of the cave … 900 yards, or just over half a mile.

[1] See Y.R.C. Journal, No. 5, vol. II., pp. 59-60, &c.

[5] Martel. Irlande et Cavernes Anglaises, p. 331.

[6] NOTE. – Not always. Experta Crede. – Editor. [“Believe one who has had experience in the matter!”]