Noon’s Hole, County Fermanagh.[1]

By E. A. Baker And C. R. Wingfield.

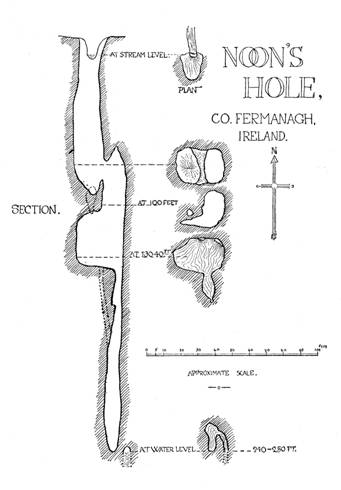

Noon’s Hole, or Sumera, the deepest pot-hole yet explored in Ireland, lies near the northern edge of the hills stretching east and west, some six miles south of Lough Erne, from Belmore to Knockmore. Pot-holes of any great depth are scarce in Ireland, no other apparently reaching further than a hundred feet. Most of the vertical openings near Marble Arch are simply cavities formed by the falling-in of roofs into underground stream-channels; those in County Clare are either of the same nature or else deep funnels down which streams make their way to a more or less horizontal underground course. There are several on the Belmore range, but in most the bottom is visible from the surface, and Noon’s Hole is the only one that in the natural course of things has come to be reputed bottomless.

It also has a romantic history. In 1826, when the Ribbonmen were troublesome in the neighbourhood of Enniskillen, a man named Dominick Noon turned informer. His delinquency being speedily discovered, his old associates decoyed him away from police protection to one of their hiding-places on Lough Erne, and thence took him one night to the hills south of the lake, a region of caverns and trackless moors, full of ancient legends of Diarmaid and Grania, where these bands used to defy the authorities. They meant at first to wreak their vengeance at leisure, but as they were passing this yawning chasm ‑ then simply called the Sumera, or the Abyss ‑ they could not resist temptation, and flung him in. Noon’s body lodged on a shelf, and was afterwards recovered and decently interred. His death seems never to have been brought home to any individual, but a number of men suffered transportation as a result of the severe measures taken to stamp out these crimes. Noon’s name has been associated with the place ever since. The Sumera was always an object of terror, as a danger to man and beast, and the entrance to mysterious nether regions; it was now an object of hatred and loathing.

A little brook flows out of the bog on the gritstone strata higher up, and suddenly coming to a joint or fault in the limestone, forthwith tumbles in running underground for five furlongs or so, and emerges into daylight again at a great opening in the face of a cliff; called Ooboraghan. Swollen by tributaries which have joined it some where in its subterranean course, it pours clown a wooded ravine in a series of grand cascades visible and audible afar. You can walk into the rocky portals of Ooboraghan. At first you are deafened by the hurtling of streams, then as you penetrate the darkness you come to deep, silent pools, where the waters well out from under huge transverse arches hanging one behind the other and plunging their shoulders beneath the surface. Behind these, the river flows first right and then left along narrow corridors. Here it was, some years ago, that a party including H. Brodrick, C. A. Hill, R. Lloyd Praeger, and E. A. Baker, tried to penetrate the mysterious region between Noon’s Hole, where the stream enters, and the point where it comes out again. Baker was the victim sent in, at the end of an Alpine Club rope, with a lifebelt round him borrowed from a Lough Erne steamer. The corridors between the submerged arches proved too narrow for swimming, too deep for wading, and the walls too smooth for any other method of propulsion; so he was forced to return with very little fresh information. The only alternative entrance was by way of Noon’s Hole itself, which is 400 feet above Ooboraghan and 770 feet above the sea.

In 1895 M. Martel had made the first attempt at an exploration from above. He descended through the waterfall formed by the brook, which he does not appear to have dammed back, and reaching a depth estimated at twenty metres had to reascend. He reported that the walls converged a short distance below him, where the pot-hole dwindled into a series of small openings, completely occupied by the falling water. He managed to send his plumb-line to a depth of 47 metres, or 143 feet, and gave this as the total depth. Nothing further was accomplished till 1907, when the party just enumerated made a second attempt to explore Noon’s Hole. Here also Baker was made the scapegoat, but he fared better than M. Martel, for the precaution had been taken to dam the stream, so that he escaped the waterfall which, in 1895, had almost blinded the previous explorer and upset his reckoning. Below the place where M. Martel stopped there appeared a natural bridge, where the stream did indeed tumble into narrow holes; but behind a projecting wing of limestone a much wider chasm was disclosed, and down this the 70-foot ladder was dropped at the end of a rope. Baker descended to yet another bridge. This was the place, 143 feet from the surface, where M. Martel’s plumb had stopped; but the pot-hole went on down still further into the interior of the earth. The tackle available, however, would not reach any further, and it was only possible by dropping stones down to try to calculate the distance traversed before they hit anything solid. This appeared to be at least 100 feet. All attempts to light up the depths below with magnesium ribbon were unavailing, for there was still water cascading down this final pitch. Valuable help was afforded to the party on this occasion by Mr. Lemon, of Enniskillen, who lent two 120-foot ropes, no preparation having been made for deep pot-holing. At this and every visit Mr. Thomas Plunkett also has, in the most generous fashion, given all the help in his power.

Here the matter rested until September, 1912. Although many people had had an eye on Noon’s Hole, and a lot of cave-exploring had been done in Ireland meanwhile, it had not been possible to muster a party strong enough for the descent, and even when the party was forthcoming its members narrowly escaped failure through a slice of ill-luck. The 300 feet of rope-ladder and life-line in proportion, sent out by the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club, were delayed on the Way from England, and did not reach Enniskillen till too late. But the idea struck the inventive member of our party ‑ Wingfield ‑ that we should make our own ladders. Enniskilllen has boats on Lough Erne, and is not without ship chandlers. We soon got manila enough to construct 105 feet of serviceable ladder and some 300 feet of life-line, which, with a few 80-foot ropes we had already, was sufficient for pulling the ladder up and down, so as to enable us to do the climb in sections. If our rough estimate of the bottom pitch was right, we could in all probability carry out the job quite safely, though not with the ease and comfort of a rope-ladder reaching right to the bottom.

Great preparations were made for engineering the ladder past the two bridges down to the final drop, and arranging the life-line to run beside it without entanglement. A hole was made in the dense thorn-bushes on one side, where a vertical wall gave a clear lead from a point 15 feet above the lip of the stream ; and a series of dams were built with sods calculated to hold the flow back for six or eight hours. Three of the party proposed to descend, and local help was available F. W. Dunn and J. Layzell, who undertook to tend the ropes. Having had experience of the hole already, Baker was sent down first, removing a number of threatening fragments as he went. The ruinous condition of the opening in several places formed the only serious danger on the uppermost pitch; but no shelter was to be had if anything happened, and it was necessary to be constantly on guard, especially when it came to shifting the ladder.

Under the mouth the interior bellies out like an enormous bottle, and is most picturesque, with deep black rifts gaping in the sides, the walls grooved and polished by falling water, and the light playing through foliage overhead. The oval shaft, 20 feet long by I5 feet wide where the stream runs in, gradually widens to a diameter of about 30 feet. The natural bridge had altered considerably since 1907, as a tangled mass of stones and brushwood which had made a false floor was now entirely washed away. There was nothing left for the first men down to stand on but a knife edge of rock between two yawning gaps, where they had to balance on half a foot each whilst Wingfield descended past them into a sort of cup with a hole at the bottom in the direct line of the waterfall, and then clambered out again, dragging up the tail of the ladder to be swung over into the adjoining shaft for the second pitch. The ladder was then let down this, and Wingfield climbed over the knife-edge and descended an almost vertical wall into the roomy chamber whose floor forms the second bridge.

Baker and Kentish followed, and candles and lamps were lighted, as only a dim light comes through the holes in the roof overhead. There were two breaks in the rocky floor ‑ one a small hole at the north end, which could be used to divert water down if necessary, the other a north and south fissure in the north-east corner, 10 feet long by 3 feet wide, nearly opposite the ladder. This we selected as the line of descent. But at this point a trying delay took place. We had sent up a message tied to the life-line, and in sending back the rope those above got it badly fouled in the branches hanging down the hole. We dare not pull hard on the twine attached to the rope-end for fear of losing our connexion, and for thirty minutes at least we stood under a cold drip, shouting and signalling without any assurance that we were understood, before we got the tackle lowered for the final descent. lt was then let down to the full extent of the ropes, which left the top rung about 10 feet below the floor of the chamber. Baker proceeded to back-and-knee down to the ladder, whilst Kentish and Wingfield tended the life-line. He found the whole of the ladder coiled up on a sloping ledge some 20 feet down, and, was supported from above while he disentangled it and threw it over. His mutterings gradually got fainter, till they suddenly resounded again through the small hole on the north, then there was a long interval of silence.

There is total darkness a few feet below the top of the final pitch, and even a big acetylene makes very little impression on account of the streaming water and the dense mist that rises. All the lamp reveals is a black pit, with straight, perpendicular. sides, very wet and slimy with disintegrated limestone, and a steady fall pattering down from somewhere overhead, in spite of the damming of the main stream. lt was not till he actually stepped off the ladder on to a kind of beach of rounded stones that Baker was able to tell that he was near the bottom. There was only a rung or two to spare, and the total depth of the hole proved to be almost exactly 250 feet.

Two whistles having sounded and the life-line being drawn up, Wingfield came down, his candle getting doused by the falling water almost immediately, and the rest of the journey was feebly lighted by the lamp from below. The bottom was a dungeon-like place, some 20 feet wide by 6 feet, with a tunnel carrying the stream away round behind a leaf of rock. Following this through a pool and down a water-course for 20 feet, one came to deep water. Wingfield waded in and was willing to try a swim, but closer scrutiny showed that there was only head-room for a little distance. This was the only opening of any sort. A piece of timber jammed in the roof of the tunnel, and a stick fixed horizontally above the arch, showed that there is sometimes a deep pool of water at the bottom. We had got down Noon’s Hole, but the ulterior object ‑ the exploration of what lay between it and Ooboraghan ‑ was as far off as ever.

Baker climbed back to Kentish, who did not think it worth while coming down, as there was nothing to explore. The problem now was how to get the life-line back to Wingfield. A big stone tied on to it fell out of the loop. Wingfield heard it coming and took shelter in the tunnel. At the next attempt he got the rope-end and came up to the ledge where the ladder had caught. Here he stayed and helped to hoist the ladder up, Kentish sitting on it whilst Wingfield finished the last 20 feet on the tail-end. The rest of the ascent was finished without incident, and the surface reached five hours and a half from the start. Next day Dunn and Wingfield went down to the two bridges to photograph and to tie a rope to the ladder for convenience in hauling up; the tackle was recovered, the hedge at the top mended, and the neighbourhood ‑ which had taken the keenest interest in the proceedings, as news of the event had been carried broadcast by the postman ‑ was left with a little more history to add to its memories of Noon.

[1] Acknowledgments and thanks are due to the Editor of The Field for permission to reproduce much of the material contained in this article.