Siberia In Winter

By S. W. Cuttriss.

In my paper “In Northern Siberia” (Y.R.C.J., vol. III., p. 17) I gave an account of a summer journey to the Northern Urals by way of the river Ob and its tributaries. What follows describes an overland journey to the same district in mid-winter.

The Ostyak village of Saram-paool is situated on the eastern side of the Northern Urals a little north of the sixty-fourth parallel of latitude. It can be approached by two routes from Ekaterinbourg, the principal mining town of the Urals:‑ during winter, partly by rail and then by sledge, in a practically direct line through the trackless forests and over the frozen swamps, a distance of 800 miles; in summer, when this route is rendered impracticable by the impassable swamps, by water from Tiumen along the river Ob and its tributaries, a journey of over 1,350 miles.

Our party included Mr. J. Findlay, of Leeds, myself, and a Russian, who nominally acted as our agent d’ affaires. Our own knowledge of the language was very meagre, and as the Russian was totally ignorant not only of English but also of the dialects of the Zaryans and Ostyaks, among which tribes we should have to mix, our means of intercourse were decidedly limited, and for all negotiations with the people of the district we had to rely on a Russian merchant on the spot.

Ekaterinbourg was left, appropriately enough, in a heavy snowstorm, on January 30th, and after a tedious railway journey of 300 miles we continued another 60 miles by sledges to Nikito-Evedil, the most northerly town in the Urals. Here we spent a couple of days making preparations for the further journey of 440 miles, during which time we should be thrown on our own resources. The temperature, as yet, was not excessively cold, being only in the neighbourhood of 0°, Fahr., but it was imperative we should provide ourselves with extra fur clothing to withstand the increased cold to be encountered later. Food also had to be purchased and the necessary culinary outfit and tools, &c., including a supply of hay for the horses. We had expected after reaching this town to discard horses and use instead the swifter and more suitable reindeer, but in this we were disappointed, as all the available animals had gone with merchandise to the Winter Fair at Irbit. Horses are not nearly so serviceable as reindeer for travelling over the open country, as being much heavier animals they sink in the soft snow and make travelling very difficult, when off the beaten track. Nor have they the same staying power, and, moreover, have to carry their own food, whereas the reindeer live solely on the moss lying under the snow in the forests.

The provisions included a good supply of fresh bread made into rings, fresh fish, reindeer meat, broosnega ‑ a red bilberry which grows in profusion in summer and is used in winter in place of vegetables ‑ tea, milk, sugar, and pilmanee. The last, which I christened “Arctic Oysters,” consists of minced reindeer meat seasoned with dried herbs. A small piece, about the size of a filbert, is covered with a thin layer of dough and then frozen hard instead of being cooked and when required to be eaten is dropped into boiling water and in a few minutes a most appetizing and sustaining meal is ready, the hungry traveller fishing out the nuggets with a pointed stick, or a fork, if he happens to be the possessor of the latter.

We took 36 lb. of this food and should have been glad of more. Necessarily all the food was frozen while travelling and we were always in too great a hurry to wait for the bread to thaw thoroughly, so while the outside was toasted the centre, was still adamant, the milk was used in lumps ‑ like sugar. The natives prefer to eat the fish and meat raw, simply cutting off the flesh like chips from a block of wood.

With best wishes for a safe journey from our good friend and host, Mr. Lawson, who had rendered us every assistance possible, we started late in the afternoon in bright, sparkling weather. The dry snow creaked pleasantly under the sledges and the long hair of the horses became coated with rime from their breath, while our fur coats and huge collars, which nearly covered our faces, were soon surrounded by a ring of white crystals. My spectacles were a great nuisance owing to the vapour congealing on them and obscuring the vision, but, at the same time, they protected the eyes from the cold wind, which afforded considerable relief.

We were now a party of four, having engaged a one-eyed Russian workman, who proved a most useful and resourceful man, so with five horses, sledges and drivers, we presented quite an imposing array. The sledge is a kind of huge basket on runners, having a. pair of outriggers to prevent it being overturned on rough ground, which, however, sometimes fail in their duty, as we found to our discomfort on more than one occasion. Baggage is first stowed away in the bottom and well covered with hay. Having encased your feet and legs in long stiff felt boots and donned a huge fur coat reaching to the ground, making you feel like an animated bundle of furs, you scramble into the sledge, the spare corners then being filled up with baggage. At. first it feels very comfortable, but the hard corners of the luggage soon assert themselves and your time thereafter is mainly occupied in trying to find a soft spot. Travelling is done throughout the day and night, with occasional halts to rest and bait the horses. Crossing the rivers, when the banks were twenty to thirty feet high, proved quite a novel experience. The sledge is simply driven straight over the bank, there is a mad rush down the steep slope and quite possibly an upset at the bottom, then by a free application of the whip the horses are persuaded to struggle up the opposite side, a result, however, only attained after probably more than one ineffectual attempt.

Bourmantova was reached on the second night and we rested at the house of a Russian, sleeping on the floor, which practice is generally preferable to courting the risks of the ordinary bed. Fresh horses and drivers had to be obtained here to take us on to Naximvol, where we hoped to be able to procure the much desired reindeer. Although we were now among the foot-hills of the Urals, and crossing over from one river basin to another, we only once caught sight of the bright snow slopes of the higher mountains towards the west. There was no change in the scenery, the same perpetual forests, crossing of rivers and frozen swamps which seemed interminable, looking like frozen lakes dotted here and there with isolated patches of trees and shrubs. There is no definite road but simply a narrow track, hardened by the traffic, which, when covered with freshly fallen snow, is difficult to locate. Once during a snowstorm the track was lost and the horses floundered about in the soft snow until they could go no further, the drivers then set off on foot to locate the proper route and after considerable delay and unmercifully belabouring the horses we once more regained the track.

One night, or rather in the early morning, we halted for a few hours at an Ostyak yourte, or village, and made ourselves at home in one of the huts. This was our first experience of a native dwelling and it proved more agreeable than imagination had pictured it. On entering through the low doorway and striking a match the room appeared to be untenanted. In one corner was a fireplace made by plastering the rough timber walls with mud, over which a canopy forming the chimney was constructed in the same manner. Round two sides was a low bench, six feet wide, and on this was piled a heap of reindeer skins. The one window consisted of a single block of clear ice. I was surprised to see hanging in a conspicuous place the emblem of the Russian Church ‑ the Ikon or Holy Picture. Although the Ostyaks are primarily a nomadic race and their religion, so far as it exists at all, is a form of ancestor worship with witchcraft and sorcery playing a leading part, many of them have now adopted a more settled life and nominally accepted adherence to the Greek faith. They still use the bow and arrow for hunting although some are possessed of primitive fire-arms. While we were busy lighting a fire there was a movement in the heap of skins on the bench and a diminutive man slowly emerged. Greeting us with the salutation “Pasha, Pasha,” accompanied by a languid finger shake, in addition to which he would have bestowed a kiss had we not been careful to avoid the osculation, he proceeded to rouse his spouse. She at once made herself busy in preparing the samovar, wiping from off the low table the fish bones and other remains of the last meal, ferreting from an obscure corner sundry gaudy cups and saucers and making other hospitable preparations. By the time breakfast was ready several other members of the family had become evident, and, with the addition of our own retainers, the hut became inconveniently crowded. No payment is expected for thus making free of their domicile and property, but we always left a few kopeks as an expression of our thanks. Later, when we had obtained reindeer, we used to travel for eight or ten hours at a stretch until we reached one of these huts and then stop for food, but often the occupants were steeped too far in alcoholism to take much interest in the proceedings. Vodka is the curse of the country and the natives will often starve rather than forego a chance of procuring the fiery spirit. The more unscrupulous fur traders, unfortunately, take full advantage of their weakness.

At Naximvol there is a small wooden church and the Russian priest or pope surprised us by retailing the latest news of the world, including the first intimation of the English national coal strike, and the latest information about the Italian-Turkish war. Although we had travelled with all speed from Ekaterinbourg and he had come from Tobolsk, several hundred miles further east, he was able to give us later news than we had ourselves heard.

We were glad to be able to dispense with the horses here and, after some difficulty and considerable haggling, contracted for twelve reindeer and four sledges and drivers to take us the final two hundred miles to Saram-paool. As the men had been busy with the vodka bottles and the deer were twenty miles away at their feeding ground on the hills we did not make a fresh start until the afternoon of the next day. The people have no conception of the meaning of hurry, as they have nothing to hurry for, and we constantly suffered delays on this account. My driver was a big Zaryan with a shock of flaming red hair and although the temperature was well below zero he preferred to drive bareheaded, not pulling up the hood of his fur coat until the air began to get a little nippy during the night.

The reindeer are harnessed three abreast. A single trace, which is attached to the collar bands on the outside deer, is passed between their hind legs and through bone eyes attached to the sledge; the centre animal is fastened by another trace to the middle of the other one, where it passes between the bone eyes which serve the purpose of pulleys. This arrangement causes the pull to be evenly distributed to the sledge, and if one animal is not doing its full share of work the fact is at once apparent by the animal falling out of line. Long slender poles are used to prod the animals behind and when guiding is necessary, which is very seldom, as they show wonderful instinct in keeping to the narrow track, the pole is used to turn the leader’s head in the required direction.

The sledge is a light wooden frame made of birch, the pieces being dovetailed together and bound with hide thongs. This construction makes a strong flexible structure which will adapt itself to the irregularities of the track without breaking. It is a common practice to pour water on the runners, which gives them a coating of ice, making them run more freely. The driver sits on the left side with his legs hanging over so as to be ready to jump off quickly when necessary. We had a light framework fitted to the rear of our sledges to form a back rest, and then, with plenty of hay and skins, we were able to either sit up comfortably or lie down at full length as desired. As each sledge only carried one passenger it was not possible to while away the time in conversation and we had ample opportunity for solitary communion.

After twenty-six hours’ travelling, with only three short rests, we covered 133 miles, very different to the hundred miles in 60 hours with the horses, proving how superior reindeer are for this work. For the first time since the start the deer were now unyoked, and turned loose into the forest to feed. In a few hours time the drivers started off on snowshoes to round up the animals, catching them with the lasso. This is often a two or three hours business, as the deer apparently much prefer their freedom.

As we travelled north the cold increased, the temperature going down to 48° below zero, and, for five weeks we never again saw the spirit of the thermometer above the zero point.

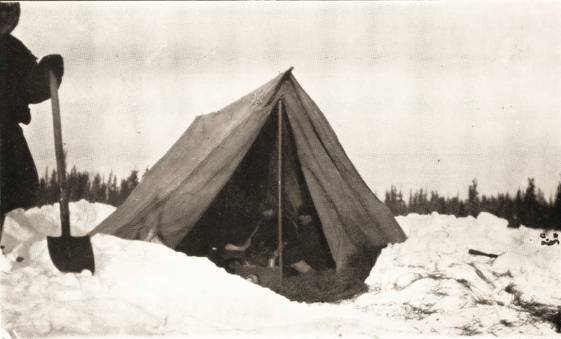

Arriving at Saram-paool, we drove to the house of Petro Petrovich, the only merchant in the district. He does a very extensive and profitable trade supplying the people with all their necessities and buying the furs brought in by the natives for hundreds of miles round. His annual turnover amounts to over £20,000. He has now taken up, his residence at Tobolsk, leaving the business in charge of his manager, Gregory Prokroprovich, who will no doubt ultimately succeed to the business, as did Petro Petrovich to his predecessor. Even here we did not escape the attention of the Russian officials, as we were visited by one of the police, who was making a tour of his district from Berezof, on the River Ob, over 300 miles away. With the exception of the neighbouring small village of Sukarinsk, Saram-paool is the most northerly village in that part of Siberia, all the country towards the mountains and the tundra to the north being only inhabited by the nomad Ostyaks and Samoyedes. As the work on which we were engaged made considerable journeys up the various rivers necessary, we took the tent which had been used during the summer two years previously and camped out for one and two weeks at a time. Our native workpeople whom we engaged at the village and the olaneckiks (sledge-drivers) lived in their own choom (tent), which they took with them. This tent is made of slender poles fastened together at the top and covered with reindeer skins sewn together ‑ in appearance very similar to the Indian wigwam. Our tent had been specially constructed for winter use to allow a stove being used inside, the chimney passing through a hole in two sheets of asbestos sewn to the canvas. A fire had not long been burning in the stove before we discovered the canvas was on fire, and an investigation showed that the makers had omitted to cut away the material between the asbestos sheets, which were therefore quite useless for the purpose intended and dropped away. Our resourceful Russian fixed a rough substitute by means of a piece of sheet iron.

The use of a wood fire in a canvas tent is not altogether an unmixed blessing. The shower of sparks from the chimney have an inconvenient habit of setting fire to the canvas, and several times, when comfortably buried in furs for the night, we had to hurry out and throw snow on the rapidly increasing rings of fire. With a temperature of 50° below zero, one does not sleep in pyjamas, but rather dons, every article of fur clothing available. Even with a good fire roaring in the stove, the lower part of the tent would be covered with hoar frost, and my moustache was frequently frozen to the fur collar of my coat. Daily ablutions, except to a very trifling extent, was a custom “more honoured in the breach than the observance.” For a fortnight at a time I never had my clothes off; and found it a practice to which one can easily become accustomed.

The natives warm their tents with an open fire, the smoke escaping through an opening at the top ‑ at least, it is supposed to do so; but, as a matter of fact, it fills the tent to within about three feet from the floor, where one has to lie to avoid suffocation and blindness. On one journey, rather than be bothered with our own tent, we decided to live with the men ‑ twelve people in a choom I4 ft. in diameter ‑ but in order to get rid of the smoke we installed the stove. Satisfaction at the result of our experiment was, however, shortlived, for although we cured the smoke problem, the hot chimney acted as an upcast shaft, and the freezing air descended through the opening at the top on to our heads like an icy waterfall. We were constrained to give the natives credit, after all, for knowing how not to warm their tents.

On one occasion, having made arrangements for a fortnight’s journey, and waiting impatiently for the sledges to arrive, one of the men turned up with the information we should not be able to start that day, as it was a Bolshoi Prasnik, or great holiday, the last day before the commencement of the Easter Fast of seven weeks’ duration. We discovered everyone intent on holiday-making, which, being interpreted, meant vodka-soaking. The principal amusement consisted of driving about the village at breakneck speed and, as our departure that day was out of the question, we made the best of the provoking delay and joined in the fun. My driver, a Samoyede, was already so far intoxicated that he could hardly keep his seat on the sledge, but we luckily completed the circuit without a spill. Later there were reindeer races on the river, and the day ended, of course, in a drunken debauch. Two days later l came across my inebriated Samoyede twenty miles up the river, looking after a herd of a hundred and fifty reindeer feeding on the hills.

The condition of the snow in these northern latitudes is very different to what we are accustomed to in this country. lt falls in fine, sharp, powdery crystals, and owing to the absence of heat from the low-lying sun, remains without packing or surface crust. As a consequence, snow-shoes are absolutely necessary for travelling in the forests where the snow has not been disturbed. Norwegian ski would not be suitable for these conditions, as they would not afford sufficient support. The native lourzhe (snow-shoes) are much shorter, between two and three times the width, and completely covered on the underside with reindeer fur cut from a particular part of the hide, the lie of the fur being backwards. They are not so fast as ski downhill and on the level, but are excellent hill climbers.

Most of the higher mountains of the Urals lie to the west of the watershed, and were therefore quite out of our range, but the main chain itself showed many an inviting crest and precipitous slope as their pure white sides stood out in clear relief against the azure sky, despite the fact that we viewed them from a distance of ten or twelve miles. One hill, rising to a height of 1,700 feet above the river, afforded me a good day’s healthy exercise in its conquest. The ascent was very steep, and in places the assistance of an axe was necessary with which to cut away obstructions in the forest-clad slopes. I recollect one place in particular where I was forced to come out on the top of a precipitous rock and then turn sharply round and ascend an ugly slope. For a novice like myself the descent proved as difficult as the ascent, and at the more trying places I adopted the expedient of walking backwards step by step ‑ perhaps not a very sporting but certainly a safer method of progression, and one which, I venture to believe, could not have been adopted on ski. Owing to the dense undergrowth and fallen timber it was not possible to adopt the broadside step, which can generally be used on smooth steep slopes.

The lowest temperature we experienced was 58° below zero, or 90° of frost, and the night following this minimum there was a very fine display of the Aurora Borealis. The natives said this indicated the approach of warmer weather, and they proved to be true prophets, as we never experienced the same degree of cold again. Naturally considerable care had to be taken to guard against frostbite, and with the exception of one occasion, when my companion, Findlay, suffered rather severely with his left hand, and once when I had a narrow escape on the top of a hill while manipulating the camera with bare hands, we had no trouble in that respect. Taken as a whole we experienced very little wind, but when a stiff breeze did blow the cold was very trying and then the tear-drops would freeze in the corners of the eyes.

When making long journeys we sometimes had trouble with the drivers owing to their antipathy to hurry. They always wanted to make a lengthened stop when we came to a habitation, and, if it happened to be during the night, we had difficulty in getting them to turn out again. On the occasion of the journey referred to, at the time of the Bolshoi Prasnik, they turned quite mutinous on the first night out, being still in a condition of sem-intoxication, and it was only by persistent firmness on our part that they were kept on the move. However, they got the better of us in the end, as waking up from a light sleep about midnight we were astonished to find there were no reindeer in the sledges and all the men had disappeared, except one Zaryan lying on a sledge in a drunken sleep. This was certainly an unexpected and aggravating predicament, but we had to make the best of it and wait until morning, when they all turned up again. It happened to be a convenient place for feeding the reindeer, so they had quietly turned them loose and then walked back over a mile to a choom we had passed on the way, leaving us to our own devices. It was on this one occasion only that Gregory Prokroprovich served us a nasty trick. We were anxious to engage the same olanechik who had served us well before but Gregory said he was away in the forest; however, he knew of another man who was very reliable, had the best deer in the country and an excellent choom. Although we were not at all favourably impressed with his appearance we were assured that everything would be quite all right. As events turned out everything was quite all wrong. On our return we learned that the man was well known as a good-for-nothing drunkard and considerably in debt to Gregory. The latter had made use of us to enable him to get square with the defaulter, as the money passed through his hands and the man received practically nothing for his trouble.

On March 17th we finally returned to Saram-paool l to make immediate preparations for the return journey south, as the thaw was threatening, and when that became established travelling overland would be impossible and involve a delay of probably three months before the arrival of the first steamer. After much bustle and interminable arguments everyone appeared satisfied, we exchanged farewells with the brothers Prokroprovich, their families, and half the village and got under way in the early evening. This time, for a driver, I had an Ostyak boy of fifteen years and he proved the smartest of the three. He was a merry soul, whistling and laughing all the day through, but as soon as night closed in his head would drop and sometimes his driving stick as well, and I had to wake him and send him back for it. We were obliged to push on with all speed, as during the day the temperature rose above freezing point, and the reindeer had great difficulty in dragging the sledges through the wet snow; the river ice also was getting flooded. Our rests were mostly made in the daytime so as to be able to push on when the night frosts had hardened the snow. In seven days we were back at Nikito-Evedil, and only just in time, as ours’ was the last party to get through. This journey of 440 miles was, accomplished in six running days and with the, same animals, an average of 75 miles per day over very difficult ground. Give me reindeer everytime!