Many Happy Returns!

By The President.

In November, 1913, the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club celebrated its coming of age with every evidence of virility and strength, and, in a moment of weakness, I promised the Editor that I would write him a short history of the Club during its period of infancy and adolescence. But while the Editor proposed the German Emperor disposed, with the result that, on the outbreak of the War, I found my services commandeered to the neglect of all outside duties. I have, however, taken French leave in order to send a few stray thoughts and to wish the Club many happy returns!

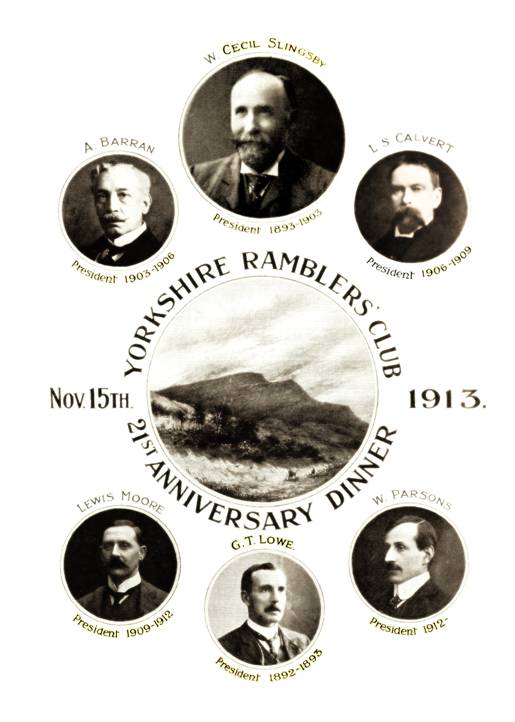

To me one of the most striking evidences of the Club’s virility is the fact that every man in the first list of its Officers and Committee is still active and vigorous. Is it not also a unique feature for any organization of twenty-one years’ standing that every President-with one exception should be in its ranks, able and willing to give assistance in a time of emergency? Not only this, but in spite of years, our ex-Presidents are just as fresh, just as energetic and vigorous as ever. Really we must ask Mr. Slingsby and Mr. Barran for the recipé of this elixir which produces perennial youthfulness. Is it that the spirit of the mountains is synonymous with the spirit of youth?

Some time ago the Registrar General made the statement that married men live longer than single men; to which a cynic replied, “They don’t; they only seem to do.” But from the above evidence I think we are justified in stating that Yorkshire Ramblers really do live longer than other men. What an excellent testimonial of membership! Apart from this, however, I am quite willing to apply the answer of the cynic to our members and to state that they also seem to live longer than other men. Was it not Stevenson who stated that a man’s life depended not on the number of years, but on the number of sensations experienced; and I would ask any member of the Club if he would have sacrificed some of those crowded hours of glorious life experienced amongst the hills “where the snows are white and the great winds blow,” or if he would have foregone the pleasures of struggles and stress in our gruesome Yorkshire pot-holes for weeks of the ordinary humdrum of existence.

Now, what has the Club done to justify the wisdom of its founders?

During the twenty-one years of the Club’s existence its members have probably ascended every important peak in the Alps, have explored the Caucasus, have corrected our school-boy knowledge of the Canadian Rockies, have practically taught the Norwegians their own country, have conquered virgin peaks of the Himalayas, have done a large amount of original work in our British crag districts have made descents-in nearly every case first descents of our Yorkshire pot-holes, and” have–thanks to the versatile knowledge of Mr. Gray and the untiring efforts of Mr. Brigg-produced a journal, now extending to a hundred and twenty pages, which can compare favourably with any magazine of a similar organization.

But, after all, the value of the Club lies not in what its members have done but in what they have received from it

I believe it was Nansen who, on being asked if the results of Polar exploration were commensurate with the waste of energy and loss of life expended in search for the Pole, replied “Man wants to know; and when man ceases to want to know, then will man cease to be man.” Is not this the foundation spirit of all our mountaineering adventure, the driving force in all our pot-holing exploration, and are we not justified, therefore, in asserting that the rock-bottom principle of our sport is, after all, akin to the principle of all human progress? If this be so, our members must be the better for having imbibed although unconsciously-something of the stimulus of this spirit.

I sometimes think that the ordinary course of town life does often mould our faculties so as to warp our power of appreciation of the “sacraments of nature.” What better antidote than our association with kindred spirits united by the common bond of love of the hills, and what better corrective for the wrangling passions of modern competition than that calm when

In the hour of mountain peace

The passion and the tumult cease.

But what of the personal friendships derived from association with such a Club as ours? Would not most of us unhesitatingly say that through the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club our best friendships of life have been formed-those friendships that will never be broken and those memories that will never die? And is it too much to assert that it was through such a Club as ours that we had given to us the opportunity of drinking to the full of that spirit of life so admirably interpreted by Borrow: “Life is sweet, brother; there is day and night, brother, both sweet things; sun, moon, and stars; all sweet things.”

In conclusion, I would like to refer to the part that I think the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club through its members should play in teaching the true perspective of the value of sport. It is a commonplace remark that many of our vices are but exaggerated virtues – thrift, carried to excess, becomes miserliness, valour becomes foolhardiness, and a natural desire for physical fitness, carried to extremes, becomes athleticism. In this mad craze for athletics – particularly by proxy – are we not confusing the means with the end? It appears to me that adoration of the crack sportsman at sixpence a head admission is becoming the cult of the day, and our sport – the pride of our English Schools – is developing in a direction which must ultimately tend to national decadence. To my mind, the first principle of any game is that it should be made for the player rather than for the spectator. As soon as the latter looms too prominently in the programme we have an intensification, of the vicarious tendency of modern life. At the present time are we not getting vicarious thrift, vicarious exercise and even vicarious patriotism developed to such an extent that there is a tendency to sap the sturdy manly independence which has always been the characteristic of Englishmen? Now, fortunately, our sport is the one which above all others demands self exertion and the one which cannot be carried out vicariously. Can we not through the ideals of our own pastime do something to instil into the minds of our young people that the value of sport does not consist in record breaking, nor even in winning matches; but in the stimulus – physical, mental and moral – which comes from rivalry in games, and that no sport is worth its name unless it tends to manliness, cleanliness, purity of heart, unselfishness and high ideals?