Mountain And Sea.

II

By Matthew Botterill.

“Sail largely into harbour or keep the seas with God.” – Emerson.

Not for me the thrills of big game shooting, of Arctic exploration, or the altitudes of Everest, for the combination of yachting and mountaineering exercises such a lure that one cannot readily tear oneself away from it.

One wants mountain and sea in close proximity, a requirement which is satisfied on the west coast of Scotland to a greater degree than elsewhere. For is not the summit of Garsven but 3/4 mile from Scavaig on the map? If the route were level it would be a quarter of an hour’s walk.

For years my great ambition has been to go to Scavaig in a yacht of my own. A former article (see Y.R.C. Journal for 1921) records last year’s failure through bad weather. This year I have been there four times – but let us proceed with the Log.

1921. April 26th. – Arrived aboard Molly with cook (A.B.) and steward (F.F.) having travelled by car from Ben Rhydding. We retired at 10 o’clock and had not then finished stowing all the provisions and tackle.

April 27th. – Further provisions arrive; shall we ever get everything stowed? We leave Tarbert, Loch Fyne, at 2.15 to try the engine. It goes all right, so we carry on to Ardrishaig and get into the canal. We pass four locks, then Molly sniffs out a tiny breeze which we cannot feel, and we drift and enjoy the charming evening with music on deck. When darkness falls we tie up to some trees in a pretty spot.

April 28th. – We reach Crinan at 2.45, thankful to be clear of the locks, and in half an hour Molly is under weigh, with a fine following wind. After passing through the tide race of Dorus Mohr, which was running strongly, up goes the mainsail and a fast run with favourable wind and tide soon gets us clear of the dangerous navigation by the Slate Isles.

April 29th. – Slacking and further provisioning at Oban whilst awaiting the mate. He turns up earlier than expected, so we leave for the wilds at 4.30 and spend the night in Loch Aline.

April 30th. – Loch Aline in the early morning light is surely the most lovely stretch of water there is, and the mountains of Mull are truly a fitting background. Under way at 7 a.m. (summer time). Skipper and mate sail Molly, whilst cook and steward prepare breakfast. Our cook is one of the few who take a pride in their preparations, and is a treasure downstairs, for he can cook bacon and eggs, prepare coffee and toast and keep Molly’s engine running at the same time. This serving of meals under way (save in stormy weather) is a great time-saver, and when the meal is ready we heave to and all eat together, or take turns at the tiller. We put into Tobermory (Mull) and then proceed round Ardnamurchan – the most westerly point of the mainland – a dismal spot indeed and best described as a geological dump. We anchor off the Island of Eigg at 8 p.m.

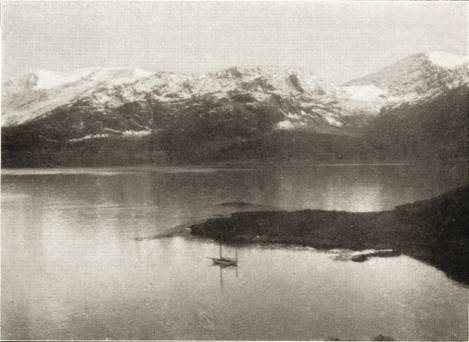

May 1st. – From our anchorage the curiously-shaped Scuir of Eigg offers great temptation to rock-climbers, but we resist it and proceed at 10 a.m. towards Skye. Having reached the nearest point of Garsven, we take in sail and proceed under power into that “Prison of shrieking little whirlwinds,” Loch Scavaig. Molly’s crew has spent much of its spare time reading of the dangers of Loch Scavaig, its dreadful climate, inhospitable boggy shores, and rocky ridges; judge then of our surprise. It was a perfect day and could scarcely have been better for entering a strange place. Anchor was let go in a flat calm at 5.15, and hardly had the chain ceased to rattle when a weird unearthly cry came from the shore. It was ominous, as though Scavaig had lured us in and the wraith of some former victim was anxious to warn us away. Possibly a bull seal!

Scavaig was wonderfully still, and the peaks so clear that they appeared to hang over and shut us in like the walls of a prison. After tea we stroll on the impressive shores of Loch Coruisk and find everything unusually dry.

May 2nd. – Skye weather begins in the small hours. By daylight the Mad Burn is once more a series of fine cascades. By 10 o’clock the heavy rain squalls and gusts of wind cease sufficiently to allow skipper and mate to be landed, but the steward, on attempting to regain the yacht, is caught broadside by a fierce gust and whipped over to Eilean Glas, where he is unceremoniously tippled out. When we on shore can again stand up we perceive the steward is safe and has recovered boat and oars, so we proceed with our climb. The route up Garsven has often been done and needs no description. The last 200 feet consists of small scree upheld by outcrops of very rotten rock, thus achieving an angle which is incredible for such a decrepit face. On this occasion it was all frozen up, or I would certainly have tried some other route.

The northerly wind is piercingly cold, though not violent, and in sheltered places we enjoy warm sunshine, and with such a clear atmosphere the views are naturally attractive. Molly lies in the black little loch seemingly at our feet. The loch is marked with white streaks, which at times develop into a surface of milk as the fiercer gusts below whip up the spray. On descending we find our poor steward still marooned on his island, where he had been kept prisoner by the fierce gusts for eight hours, without food or a smoke and with no means of communicating with the yacht; seals his sole company. He is now an authority on seals. We await a lull, then steward drifts to the shore, and with joint efforts we regain Molly, where is provided a meal worthy of the occasion. Sitting in the snug cabin with pipe and glass we enjoy in retrospect the adventures of the day.

Scavaig having now justified its reputation, the next day sees us dragged out of our berths at 5.30 by the cook, who once upon a time saw Scavaig in a south-westerly gale and is genuinely anxious to get away, so we creep out of the little anchorage at 6.15, like guilty burglars, before it wakes up. During breakfast we clear Rudha nan Easgainne (pronounced on Molly as “Ruddy Gas-engine”). A word of apology now for taking liberties with the Gaelic. When you realise that Camus Ffhionairidh is pronounced Camusunary, you will perceive that our Mollyfied method is probably no further off than any honest Saxon attempt would be, and our versions have the inestimable advantage of being easy to remember. On rounding the Point of Sleat we take a last glance back at Scavaig and see that a snowstorm is in full progress. When crossing the Sound of Sleat we solemnly commit to the deep the remains of a duck which had become “high.” By reversing the only stiff collar on board Molly we create the Rev. W.P.I., who reads the burial service from the sailing directions. Meanwhile the storm over Skye is in hot pursuit and has already enwrapped Rum, and we reach Mallaig at noon just as it breaks there.

We must now cut out detail; how the mate was dared to walk the streets of Mallaig in a dreadful tammy and did it, how we played billiards when all on shore (including the table) appeared to be rocking, and all scores were from opponents’ misses, how the mate refused coffee and tea in favour of Instant Postum, which from being nicknamed “Insane Custom” ultimately became known on Molly as “Constant Piston,” in honour of our auxiliary engine’s untiring efforts; these and other things must be cut.

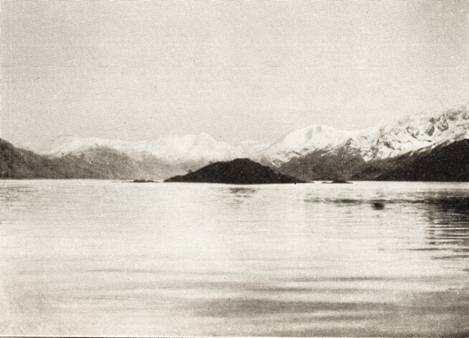

On the 4th we enter Loch Hourn (the Loch of Hell) in a double reefer with hail – things get adrift in the cabin, the rice pudding is found careering on the floor. The cook, economical soul, saved a lot and served it later as sauté de riz. Above 1,000 feet the mountains are clothed in snow, part in black cloud and part in vivid sunshine, affording views which defy description.

May 5th. – If in later recollection one day should stand out more than another surely it will be this one. We leave our anchorage by Eilean Rarsaidh at 7 a.m. in bright sunshine, astern the snow-tipped serrations of the Coolins, to port the fine sweeps of Ben Scriol, on the starboard hand the snow-filled corries of Knoydart stretching away ahead to Laoar Bheinn, whose thousand foot rocky precipices stand out darkly against the gleaming snow gullies, beneath us the lightly rippled surface of blue water. And all this on a hot summer-like day

which tempts one to swim. I have made a note of Laoar Bheinn as a suitable hill on which to climb.

As this glorious day wanes, we turn into Loch Nevis (the Loch of Heaven), anchoring by Glaschoill as the weather turns “sick” and we are soon in for a dirty night. In the Loch of Hell it was heavenly, but in the Loch of Heaven it rains like – like it does rain in Scotland. A day or two later we are in Rum, noting the fine rocky ridge which leads to the summit of Askival. We round Ardnamurchan once more without undue anxiety, for though the Atlantic roll is 50 or 60 yards across, it is easier to deal with than the shorter steeper seas of the lochs. As a result of much discussion, Ben Nevis is our next objective, and we accomplish a record sail from Tobermory, shooting the Corran Narrows when the spring tides are running their hardest. We have a commanding wind and are ejected at the other end like a pea from a pea-shooter, but even with the strong favourable wind it is no easy matter to keep Molly on her course through the whirlpools and eddies.

May 10th. – We remain in our charming little anchorage opposite Fort William until the rain ceases at 11 a.m., and I then go ashore for lunch, which proves more expensive than satisfying. We leave the little town at 2 p.m., and under the misguidance of the cook waste some time on the wrong side of the Glen Nevis stream looking for a bridge which is no longer there. The stream was in spate, and its crossing ultimately cost us a wetting. He then led us up the tourist track, as we had started too late for tackling a long ridge climb, and a very wearisome track it proved, for it seems to have been planned to miss all the impressive views the mountain undoubtedly affords. What a grind! It was 7 p.m. before we reached the Observatory, and only the roof of it was showing, the rest being lost in drifts. The summit was so heavily corniced that I am sure we could not have fought our way up any of the climbs without ice-axes. For a few moments before descending the mists cleared and afforded a really remarkable view. Hundreds of mountain summits were visible and all the giants among them marked out with snow.

June finds us again in these northern waters. There is not space to describe Molly’s circumnavigation of Skye. The mountains of Storr and the Quiraing may not offer such excellent climbing as the Coolin, but I am sure they would provide most interesting rambling.

Exciting adventures must be dismissed with the mere mention. We enter Portree under close reefs, and at a critical moment the Primus flares and sets cabin curtains alight, we pass Floddigay all lichen-covered, half in pale green and half in vivid orange, we round the northern headlands in tide-races and pass close to the queer-shaped rocks of Fladdachuan, and once we find ourselves adrift from our anchorage and ultimately come aground. Nor can I do justice to the magnificent cliff scenery, the caves and outlying islets, all of which exercise savage fascination rather than charm.

In a forsaken bay on the west coast of Skye we fill up our census return, on the same form that is supplied to a liner, with space for a few hundred names. It seems an impertinence to spoil such lavish stationery with a modest total of three names.

The longest day is marked by an attempt on the south face of the Scuir of Eigg (see below), and Molly’s fourth passage round Ardnamurchan is in a south-wester, a dead beat, with all landmarks obscured by rain and spray.

Many pages of the Log follow, devoted to charming exploration of lochs and islands, of a peep at Glencoe, of experiences with seals, of a rope ascent to an eagle’s nest, of a whale which “blew” alongside Molly. “Why don’t you carry a harpoon?” asks my fourteen-year-old crew, though what we could have done towing, or being towed by a 30-feet whale I don’t know. The final cruise (September) is the most exciting of all, for we enjoy a unique day on the highest summit of Rum, a week-end of struggle in a gale in Loch Scavaig, during which Molly saves another yacht from the rocks and is presented with a sextant, and we successfully weather Cantyre in a distressing tide-rip (112 knots in 21 hours), without any relief from constant pitching. That last sail brings us to Tarbert, Loch Fyne, and Molly commences her long hibernation.

The Scuir Of Eigg. – As we breasted the slopes of the Scuir two eagles could be seen circling the summit. Reached the rocky cliff which overhangs on its east face. The south face is almost vertical, and is undercut above the talus. Across the face a little less than half-way up there runs a shelf almost horizontally. One or two chimneys cut deeply into the cliff being continuous above and below the “Shelf.”

We traversed . to a wide fern-clad gully, which cuts the precipice diagonally. Up to the shelf it was a beautiful rock-garden, but in spite of apparent ease it required the rope. At the shelf, the gully resolved into three chimneys. We tackled the first on the left hand and found it very stiff; a 10-feet pitch two-thirds of the way up had to be turned on the right buttress. Within 30 feet of the top the final pitch stumped us. I tried to traverse the right buttress and get into chimney No. 2 which, at this elevation, presented no further difficulties. The key to this traverse, the only available hold, was a small projection which proved loose, so we had perforce to descend, using the double rope on two pitches. Meanwhile bad weather had overtaken us, and we hastily retreated to the yacht and played chess all evening. I can face this beating philosophically, for does not the true joy of life consist in the honest effort to achieve rather than in achievement?

Askival, Isle Of Rum. – A party of three (M.B., with Messrs. C. O’Brien and J. Wells) walked to the col between Alival and Askival. After lunch we proceeded up the ridge to the summit, and it proved a most interesting and varied climb. A partial clearance of the mist revealed a fine crag face, which one does not suspect when seeing the summit from seawards. One should be prepared to make first descents as well as ascents, so we took for our line a thin crack which seamed the most prominent buttress. Mist made some of the pitches greasy and rendered the doubled rope a useful help to the last man. I am sure it will go as an ascent, with an occasional shoulder from the second man.

Traversing along the scree we came to a great rock couloir and had tea on a perched slab. Skipper (leading) was assisted on to a sort of mantelshelf, whence commenced a climb of great severity. Forty feet up one comes to the foot of a sloping chimney, a replica in miniature of that in Slanting Gully, Lliwedd. It has the greasy crack and the alternative slabs and is about half the length of its Snowdonian pattern. The holds were like a well-fatted frying pan, and though the leader got up the crack, the others wisely took to the slabs.

Above this we were confronted with an ugly place, the chimney being crossed diagonally by a layer of decrepit trap (?) rock. After 30 minutes’ vain effort this was turned by an awkward traverse to the left, leading us above the difficulty and showing us what a treacherous place it was. It was now an easy walk to the summit again. To the uninitiated to be on the summit is the reward for much otherwise useless labour. The climber soon learns to do without such stimulus; finding his pleasure on the way up, he can dispense with the view, which is so frequently denied him by mists. We had had a splendid day and accomplished good pioneer work, so that we asked nothing more of fate, and fate chose to be generous.

From the summit the masses of cumulus below were much broken, revealing the Outer Hebrides, the mountains of the mainland, and those numerous islands that dot the surrounding seas. The distant mainland was a peculiar luminous green. As we looked at the mists obscuring the seas below us there formed the Brocken Spectre, one’s shadow encircled in a prismatic halo. It was not a scientific phenomenon, but a spiritual experience. Our talk was hushed, for what is man in the great creation? The earth itself is but a speck of dust in a star-strewn heaven. . For a brief instant we trod the peaks with the Creator. .The shadow faded, the luminous green changed to pink, and from deeper rose to purple. .It was quite dark before we once more reached the shore.

Note On Pronunciation.

Gaelic or Erse spelling appears to have been devised by someone with much too fine an ear for phonetics, and in the search for light on pronunciation one is continually reminded of peculiarities which have been also retained in English spelling. To the simple phonetic Welsh spelling Gaelic bears somewhat the same relation as English does to German. Scotsmen, as a rule, take no interest in the pronunciation of Gaelic names, and the difficulty of obtaining information is so great that the following attempts are given as the best the Author and Editor can do, rather than ignore the matter. A grave difficulty with English and Scottish spelling is that the commonest vowels in the language cannot be represented with certainty in print.

Eilean Glas, Ellen Glass.

Rudha nan Easgainne, Ru-a nan Essgann’ or Runa Essgann’.

Eilean Rarsaidh, Ellen Rarsy or Ellen Rarsee.

Ben Scriol, Ben Screel, probably almost two syllables, Scree-ol.

Laoar Bheinn, somewhere between Lur-ar Vane and Lur Venn. Scottish name is Larven.

Glaschoill, Glasscholl (Scottish ch).

Eigg, Egg.

Mhor, Vore.

Scavaig and Mallaig, Scavag and Mallag, unless these names are a Scottish version of the Gaelic.