A Traverse Of The Langkofel By The North-East Ridge

By F. S. Smythe.

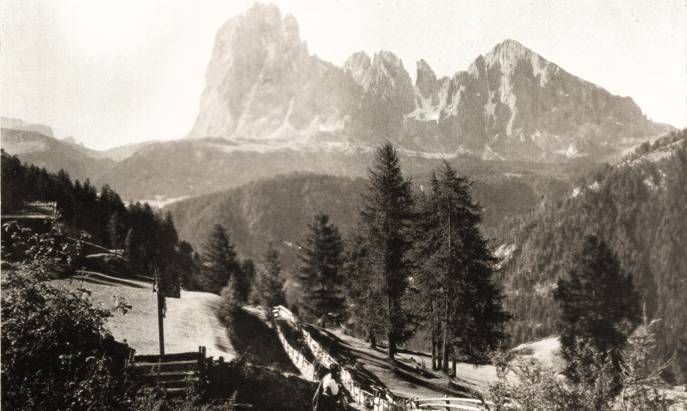

On July 27th, 1923, T. H. Somervell, his brother, and I left the comfortable inn on the Sella Pass, between S. Ulrich and Campitello, intending to climb the 3,000 foot north-east face of the Langkofel. This great rock wall, which rises like some titanic reef above the gentle pasture-clad hills to the south of the Grodner Thal, seamed by gullies and intricate with every form of rock structure that can be manufactured by the extravagant agencies of weather on the rough dolomite material, had long been an ambition of mine, and indeed I had cast envious eyes upon its splendid ramparts during the previous summer, but the weather then was always unfavourable for such a long climb.

It was a perfect morning at the hour of five, with a faint hint of frost in the air, and a pleasant walk through the “stone city,” the name given to a collection of mighty boulders fallen at some previous age from the Langkofel Eck, and up the edelweiss starred pastures to the foot of the corner where the north-east face of the Langkofel sweeps round to the yellow precipices of the Langkofel Eck.

There we paused for a few moments, to watch the sun creeping across the glaciers of the Dolomite Queen, Marmolata, or lighting with warm rays the cold grey peaks.

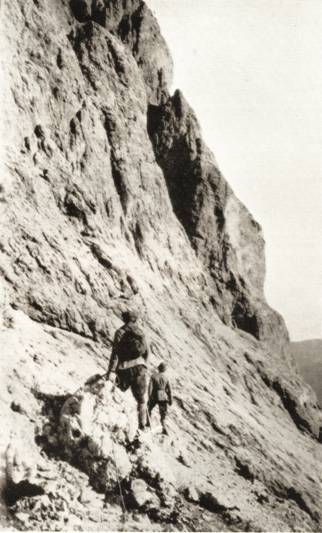

Anybody examining the Langkofel from the north-east cannot fail to notice a wide terrace running across the face for a distance of nearly half a mile and about 800 feet above the foot of the rocks, both ends of which have been proved to be accessible from below. The way to the northern end lies up the difficult rocks of a wide gully, dangerously exposed to falling stones, and to the other up a long, easy and safe chimney. Between these two routes are formidable overhangs dripping with water. With the exception of the initial pitch, which I boggled very badly and was ignominiously hauled up, the chimney of the latter route was delightfully easy and soon brought us to the terrace.

Seen from below or from a distance the observer could hardly form any idea of this great ledge of shattered rock, above which rises a wilderness of ridges, buttresses, gullies and towers. We walked easily along it for a considerable distance, keeping under the rocks as far as possible to avoid falling stones, and examining the route up the impressive buttress at its end, until it became necessary to climb up an easy face to a yet higher terrace, which led across to a gully slanting up to the nose of the buttress.

It was then about 8 a.m., so we sat down on the scree under some protecting rocks and ate second breakfast. It was not, however, an altogether safe locality, for we were almost in the centre of the wide stone-swept gully, and sun and wind were loosening the stones above. We had barely finished our meal when a stone came, with an unpleasant noise like a ricochetting rifle bullet, so hastily packing our things we fairly bolted across the dangerous area, well aware that a stone the size of a farthing will neatly crack the skull at a range of 2,000 feet.

The gully started with a big damp cave pitch, which was turned by steep and not too sound rocks on the right. Snow and ice followed, on which the one ice-axe we had brought justified its inclusion in the party. One or two more pitches led to a gap between an outstanding pinnacle and the crest of the main buttress. We were uncertain what to do next, so explored a ledge on the right of the gap.

It soon petered out into a hopeless wall, the view down the sombre sweep of which, to the gay pastures of the Grödner Thal dotted with tiny chalets, was most impressive. The only other alternative was straight up the crest of the buttress from the gap.

The first few feet were steep and then we worked to the left into a pleasant chimney on easier ground which, however, was loose in parts. At the top of the chimney the impending wall of the buttress forced us to the left until we reached a place where further progress was barred. Above rose the vertical yellow wall, subtly tempting in its abundance of obviously loose holds. Somervell first of all attacked this, but was soon forced to return owing to the dangerously loose material. He, moreover, reported it as quite vertical and with no prospect ahead of easier ground. The only alternative, and one which on my part provoked pessimism, was across to the left. There again the rock was mostly yellow and rotten, but in the critical part where it was black it was sound enough, and Somervell with the spare rope tied on as a safeguard, climbed quickly across and upwards to a corner round which he disappeared. Almost at once came a cheery shout “It goes. Come on.” It had proved not nearly so bad as it looked, owing to the ample and satisfying handholds, but nevertheless it was extraordinarily exposed and sensational.

A good chimney was a pleasant relief after such trying route-finding, but a steep loose pitch soon forced us to the left into another chimney. At first steep, the angle gradually lessened till at last we felt we were making height quickly, as moving all together we scrambled up two or three hundred feet of easy rocks to the North-east Ridge which, as far as we knew, we only had to follow to reach the summit of the Langkofel. However, we sat down to lunch in a hot sun conscious that, though the worst of our difficulties had been overcome, a long serrated ridge, studded with rickety pinnacles and cleft by numerous gaps, lay before us.

Long ere we reached this point my climbing shoes, brand new ones, in use for the first time, had begun to suffer on the sharp dolomite rock. Now they were being rapidly torn to bits and the future prospect was by no means cheering.

It was after mid-day and we did not stop longer than was necessary to make considerable inroads into the delicacies that the Somervells invariably produce in a way worthy of the best traditions of St. George’s Hall.

The weather was evidently on our side, for the sun blazed down from a cloudless sky and there was as yet no sign of the afternoon thunderstorm, so common in the Dolomites, and which we devoutly hoped would not come at all. It is a poor compliment being employed as a lightning conductor on a sharp dolomite ridge.

Interminable edges, crazy pinnacles, and annoying gaps followed. At length came a level snow ridge abutting against a steep face of rock, which, however, did not offer any difficulty and landed us on easier ground, up which we scrambled quickly to the summit ridge and to the top of our peak, which was reached at about 2.30 p.m.

The ascent of the great face had taken nearly nine hours and it was a pleasant relief to relax taut muscles in a short but welcome rest, with our reward, or perhaps I should say part of our reward, in the magnificent panorama of which the Langkofel is master. It stands as an outpost of the rugged ranges to the south and when the eye is tired of these restless Dolomite forms it turns for relief to the tender undulations of hills to the north and the ordered line of the snowclad Alps beyond. But always the vision returns to the peaks of the Langkofel group itself, which, though lower, lose none of their grandeur as they rise cliff on cliff, buttress on buttress, and pinnacle on pinnacle, from the shadowy gulfs of the Langkofel and Plattkofel Kars.

Half an hour passed all too quickly, and we turned to our guide book for details of the ordinary route off the mountain, but it offered only vague information to those whose knowledge of the German language was as limited as ours!

First of all we descended to a gap and climbing up the far side followed the ridge beyond. Here I unroped and scrambled over easy rocks on the west side to explore any possible route in that direction. But in spite of remnants of cairns it did not look promising, so I rejoined the others on the ridge, which we followed until it suddenly dropped in an overhang, Somervell attempted to descend on the eastern side of this but had to come back, so we returned until an easy chimney on the same side presented itself. Splendidly sound rock in the chimney and then on the right wall led to a ledge which ran across the face and rejoined the ridge below the impasse.

The book said “make for a conspicuous yellow pinnacle,” but pinnacles to the right of us, pinnacles to the left of us, pinnacles all round, laughed at the book, so dismissing the text in a few contemptuous and well-chosen words we started off down the west face, hoping to strike the gully leading down to the Langkofel Glacier.

This did indeed land us at the foot of an outstanding yellow pinnacle, where we had a meal and a fierce discussion as to whether we should descend on the right or on the left of the pinnacle, On this point the book remained obstinately silent, so we decided on the easier looking way on the right and a gully was followed which eventually led down to considerable patches of snow and scree, to the left of which, in a small col, we saw a cairn that proved to be at the head of the 800 foot snow‑filled gully leading down to the Langkofel glacier. Fortunately the snow in the gully was in excellent condition, but even so it took time with only one ice-axe in the party, and we were further delayed by the almost complete disintegration of my shoes. Gloves and handkerchiefs were called into play as substitutes, but all the same it was chilly work moving step by step down the snow.

At length we could glissade and bumped merrily down the last slope on to the queer little Langkofel glacier. We had no time to waste, for the sun was getting near the horizon and the crags around were becoming a warm ruddy brown in his declining rays. The way for some distance was easy and we hurried down, following the cairns erected by previous parties, but towards the end the rocks steepened and we took to a chimney.

The sun had set and the Spirit of Night was gathering his forces in the silent Langkofel Kar as we scrambled down the last rocks and jumped thankfully on to the yielding scree, but suddenly, as if angry at the resistless march of night, the sun flashed forth once more from between a distant line of cloud and the horizon, and lit with an exquisite gold the peaks around. For a few moments the gaunt crags of the Fünffingerspitze glowed – a vast ruddied land, then faded into a deathly pallor and stood hard and defiant against the unfathomable blue of night.

It was a painful trudge for me up over the screes to the Langkofel Joch in practically bare feet – never before had I realised how sharp Dolomite screes really are ‑ but owing to the thoughtfulness and endurance of Somervell who, going on ahead to the Sella Joch inn, fetched my boots and brought them a long way up, I was enabled to get a good run down over the last part.

The night was perfect as we descended the last slopes towards the comfortable little inn, but in the south a constant flicker of lightning lit noble masses of cumuli moving in stately array over the distant plains beyond the ragged forms of the age-torn Dolomites.

The cheerful lights of the Sella Joch inn ahead were too suggestive of supper to let us delay and soon we were rapidly assimilating that commodity and a certain amount of liquid refreshment.