A Brief Visit To Jotunheim

By C. E. Burrow.

On Thursday, July 5th, 1923, at 5 p.m., four Ramblers left Newcastle for Norway-their main objective the Store Skagastölstind. They intended to climb other peaks, but had they not “got” that particular Tind the holiday would have been incomplete. Truth to tell, one member of the party had been “knocked back” by the grand old peak some ten years earlier, and perhaps it rankled.

After carefully working out the correct sequence of boats and trains, they met their first reverse on the quay at Newcastle, finding that the ancient bark scheduled to sail that particular day had been obliged to put into dock for repairs, and that an elder sister with a bent propeller shaft (this latter confirmed by two of our pot-holers exploring the shaft tunnel) was to take them across the North Sea and land them in Bergen in about 42 hours. The passage was quite smooth, apart from the disturbances caused by the propeller shaft aforementioned, and the party reached Stavanger in good condition the following midnight, when the thirsty ones spent a short time in a careful study of “Prohibited Hours.”

Reaching Bergen on Saturday too late for the morning train, they whiled away the time until evening. The day was hot, and they were glad to leave by the evening train, which arrived at Myrdal with its delightfully snowy surroundings about midnight. Shouldering heavy rucksacks they began the walk down the Flaam valley. Magnificent under all conditions, this valley with an abnormal amount of snow, for July, on the mountains was delightful in the Norwegian twilight. The night growing lighter and the party having got well below the snow line, they stopped and cooked their first breakfast; this finished, another mile or two were covered and an attempt made to get a little sleep by the way side. Deciding after a time that sleeping out was an over-rated amusement, they trudged on, made a second breakfast about 7 a.m. and slept for an hour or two in the warm sunshine.

Reaching Flaam about noon, as no boat left till 8 p.m., it was decided to walk along the side of the fjord to Aurland and, after a bathe on the way down and a generally lazy Sunday afternoon, this was reached in time for a meal before catching the evening boat to Laerdalsören. It proved more difficult than anticipated, as the staff had overlooked the fact that the evening steamer did not call at Aurland. Under the circumstances it was necessary to charter a small rowing boat, complete with a Norwegian youth, to row the party out, stop the steamer and last, but not least, to get on board. Some hours earlier, people on the boat from England had admired the way the pilot came on board outside Stavanger, but these people had not seen Yorkshire Ramblers come on board with heavy rucksacks, a coil of rope apiece and ice-axe in hand! Why are not pilots trained on the rope ladders at Gaping Ghyll?

The boat was due to reach Laerdalsören at midnight, and the original intention was to walk through the night again in a general northerly direction to Natviken on the Aardals fjord, thence up the fjord by rowing boat to Aardal, by motor boat up the Aardalsvand (lake) to Farnes, walk up the Utla valley to Vetti, thence up Midtmaradalen to Skagastölshytte (5,800 feet), where we intended to stop one or two nights and climb from there. This would have meant some very heavy going and also involved carrying a good deal of food and equipment, but would not, under good conditions, have taken any longer than going by the fjord steamer to Skjolden and walking up to Turtegrö, the usual approach to the Skagastölstindern. The reason it would not have taken longer is that very few of the fjord steamers run in connection with the boats from England.

However, on getting on board, our party were informed by the captain that owing to the very late spring the quantity of snow in Jotunheim was abnormal, that no motor boat was running on Aardalsvand on account of ice, and that we should have very great difficulty in following our proposed route, if, indeed, it were possible.

Under these circumstances we decided to sleep at Laerdalsören (it was Sunday and we had not been properly to bed since the previous Wednesday) and catch the first steamer to Skjolden. This was due to depart 2 a.m. Tuesday, which gave us the whole of Monday at Laerdalsören.

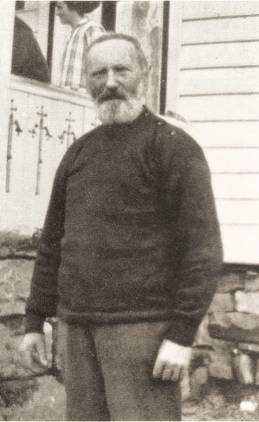

After a very magnificent breakfast we took the opportunity of telephoning Ole Berge at Turtegrö and learnt that the mountains had been quite unfit for climbing, but that he thought the Store Skagastölstind would be now possible, though no one had climbed it that year.

The day was spent on the mountains south of Laerdal, in very delightful surroundings; we returned for our evening meal at 10 p.m. and caught the early morning boat, reached Skjolden on Tuesday afternoon and, after a very hot walk, Turtegrö, where Ole Berge made very welcome members of the Club of which his old friend Slingsby was President for many years.

With every indication of good weather for the morrow, we arranged to make an early start for Store Skagastölstind. Leaving the hotel at 7 a.m. our party followed the usual route up Skagadalen and, although it was July 11th and the weather was warm, the lower lake as well as the one at the foot of the Skagastölsbrae were both frozen and we had to make steps up two long snow slopes before reaching the glacier. This was crossed without difficulty, most of the crevasses being plugged up solid with snow, nor was there sign of a bergschrund when climbing up to the Skagastölshytte in the band or col leading over to the Midtmarabrae. Being a guideless party, however, we took the precaution of using the rope.

In passing, it is remarkable to note that Norwegian and Swedish parties with apparently the most elementary knowledge of mountaineering seem to wander about on many of these glaciers. Particularly is this remarkable when a mountaineer of the experience of W. C. Slingsby mentions in “Norway, The Northern Playground,” noticing “on that usually innocent looking northern glacier (the Skagastölsbrae) one of the most dangerous crevasses I have ever seen.”

We spent some considerable time at the Hytte preparing a meal, putting out blankets to dry &c., for we were only the second party to reach it. We had no need to hurry, not having any darkness to consider.

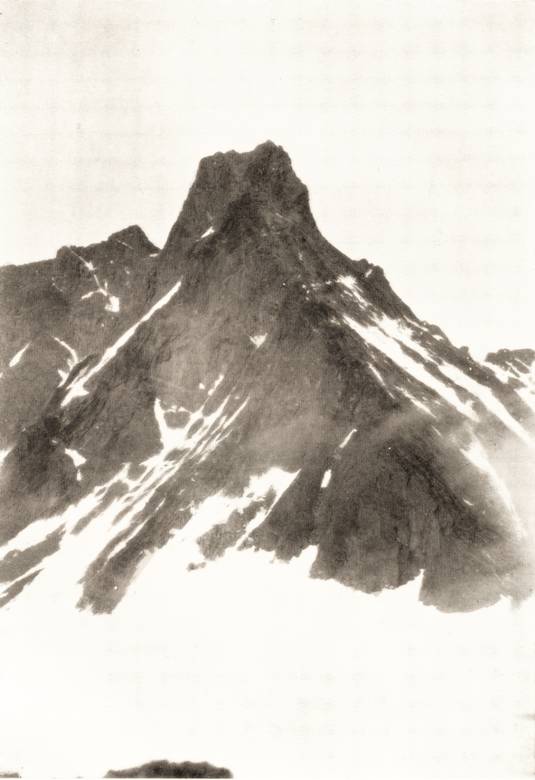

Leaving the hut we followed the ridge shown in the photograph (taken from the Axe on the Midtmaradalstindern a few days later) and encountered very little continuous difficulty and hardly any snow until reaching the higher shoulder seen on the right side of the peak. Passing over this we made an exposed traverse for about 200 feet (not shown in photo), with a sheer drop of approximately 2,000 feet to the Slingsbybrae below us, a most delightful situation, with magnificent views of the surrounding peaks. At the end of the traverse we reached the foot of Heftyes Rende (chimney), which fortunately was free of ice. This is difficult to enter, and the leader found it necessary to make nail marks on the second’s shoulders and head before effecting a lodgment. (Tricounis grip better on bald heads than ordinary nails.) Once in the chimney about 30 feet of straightforward back and foot work landed the leader on a good stance with belay (which can be used as a piton for the descent of the last man), where the second joined him after a little tensile persuasion.

The mistake was then made of trying to continue up the chimney, loose rock being encountered and forcing a somewhat delicate retreat. A good route of only moderate difficulty was then found on the left wall, the other two members of the party came up after similar attention from above, and another 150 feet of climbing of moderate difficulty landed the party on what appeared to be the summit, but proved to be divided from the real one by a gap. At this point we regretted having left our last axe on the traverse below, as the final rocks had a good deal of ice on them, but a further examination revealed a feasible route to the top (7,800 feet), which we reached about 5 p.m. In perfectly clear weather we had a magnificent view of the surrounding peaks, and with no considerations of darkness to worry us we lingered there for some time, our last man leaving the summit at 6.30 p.m. The descent was made without incident, following the same route, the lower slabs proving rather destructive to the nether garments.

We stopped to make a meal at the hut and it was after midnight when we reached Turtegrö. Ole Berge soon had an excellent dinner ready for us – he saw us with a telescope on the top of “Store” and calculated accordingly – and seemed as delighted as we were that four “Englanders” had made the first ascent of the year. Fancy getting a dinner at that hour and welcome of that sort at some of our English hotels!

We went to bed about sunrise after making adequate provision for a probable thirst during the night. Rising about 8 a.m. the same day we spent a lazy morning and visited the Riingsbrae in the afternoon. Normally there is a very fine ice cavern at the foot of the glacier, but we could not see much of it, though one of the party indicated where it was by partially falling into it.

Next day was cold and we made a start about 8 a.m. for the Soleitind, approaching it by way of the long ridge on the east of the Riingsbrae. The clouds were down to about 5,000 feet, and though we were out for 12 hours and had some sporting climbing, particularly up a gendarme which subsequently proved to have an easy side, we did not get our peak owing to being unable to locate it with certainty.

The day following we set out for Mellemste (or Middle) Skagastölstind, but could not find it for clouds, so took a compass line across the glacier to the “Skag” hut, where we stayed for some time until the weather cleared. The late afternoon became very fine, and we spent some time getting up on the Midtmaradal side to take photographs of Store Skagastölstind, from which the illustration was selected.

The following day being good weather we skirted round the foot of Riingsdalen into Soleidalen and made a route up the Soleibrae to the top of the Soleitind. Avoiding the schrunds we kicked steps up a snow gully, which later became very steep, the snow being succeeded by ice which required careful cutting. This brought us out in a narrow col, which on the other side dropped steeply to the Riingsbrae and gave us a glorious view of the Skagastölstindern as a whole, with the Riingstindern in the near distance. The Soleitind rose steeply on our left. At this point, No. 2 of our Skag party, who had led so far, suggested that the leader of the Skag party (who was climbing No. 4) should take over, which after some persuasion he did. He then understood why No. 2 had been so insistent, because on having a good look at the proposed route it did not appear feasible for anyone under about “3 Frankland Power.” After duly thanking him for the implied compliment, No. 4 found a more reasonable route on the S.W. side, which gave pleasant, not too difficult climbing to the summit.

After spending some time on the top, we found a cairn at the northerly end, which indicated the top of a very steep face, leading down to a gap at the foot of the gendarme we had climbed two days earlier, so that we had been within a few hundred feet of the summit on that day. Once the gap was reached a short climb up the other side landed us on the Solei Ridge, which gave splendid views down both sides, on the left the Soleibrae, on the right the Riingsbrae, from a crest only a few feet wide, narrowing every few yards to a foot or so.

At the end of this ridge a succession of gentle snow slopes led us down again to Riingsdalen and so back to Turtegrö.

This was our last climb, for the next day was wet and our party not averse to a lazy day. The following day two of us left for home by steamer from Skjolden and the other two went for a 14 days’ tramp, setting off in a northerly direction and covering a lot of very interesting ground.

Climbing from Turtegrö was voted a great success. In the first place any Rambler going there will meet with a royal welcome from Ole Berge; in the second place there is no question of “queueing up” for your climb, for only once out of our five days in the mountains did we see a human being, even at a distance. The trouble is that for a short holiday so much time is taken in getting to your centre, but reaching it as we did the journey was almost as interesting as the climbing.