Some Severs

By Miss M. Barker.

The Central Buttress of Scawfell was first climbed in 1914 by S. W. Herford, G. S. Sansom, H. B. Gibson, and C. F. Holland, again in 1921 by C. D. Frankland and B. Beetham, in 1923 by A. S. Piggott, M. Wood and J. B. Meldrum, and on August 18th, 1925, C. D. Frankland and I made its fourth ascent. Frankland is thus the only man who has been up it twice, which, of course made it possible for us to climb it as we did, straight through, with a minimum expenditure of time and energy and a maximum of enjoyment.

We had talked of attempting it in 1924, but no opportunity offered. On August 17th we got back from Skye, splendidly fit, and as the following day was fine we, with the rest of the camp, took the corridor route to Scawfell in leisurely fashion, trying to look and feel as though we had no special project in mind. But after lunch in Hollow Stones we went right on to the climb. Our late start was partly a strategic move to give the rocks time to dry, for the morning had been misty. We found them dry, and of course wore rubbers, but C.D.F. says much lichen has grown on the climb since his former ascent, and that consequently it was not quite in perfect condition.

For the first part of the climb I felt nervous, and said so. As a matter of fact I would certainly have climbed better had we done something rather more modest by way of prelude, for most of us probably get ” warmed up ” after the first hour. But it was partly due to respect for the climb. The Flake Crack ! One could not approach it without some awe and reverence, some sort of mental prayer and fasting.

I am a bad hand at writing up a climb, for I simply cannot remember the detail. When people ask me, ” How did you like so-and-so ? ” mentioning some tit-bit, I am usually driven to reply vaguely, ” Oh, it went all right,” because I simply don’t know what they are talking about; and am thereafter left with a horrible suspicion that I must have taken some alternative and altogether inferior route, and have never done the real thing at all. If a description of the climb is available I read it up afterwards to see what we are supposed to have done, often coming to the melancholy conclusion that the suspicion is justified ! But one cannot get ” off the climb ” on the Flake Crack, nor can one forget it as a great experience.

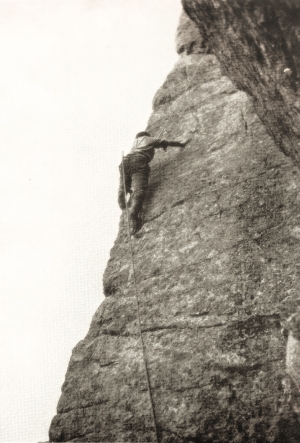

The first part, up the rib and on to the Oval, was just good stiff face climbing, with small but sufficient holds. Near the foot of the Flake C.D.F. paused in thought. We were using an 80 foot rope (which proved ample), and there was the question of that wretched thread belay. We both knew it would not be wanted, but of course it had to go on. He got up a few feet, and I came to the foot of the Flake. There is a good ledge to stand on, narrow but comfortable enough, and a jam for the left hand and arm in the crack, but nothing for the right hand: a position where the Second can wait, safely and comfortably so far as he is concerned, for any length of time in reason, but where there is no justifiable safeguard for either if the leader comes off during the difficult business of getting the rope over the chock-stone higher up. We therefore spent about twenty minutes, at a guess, of precious time and nervous energy, he trying to induce a loop of rope to pass behind a small chock-stone high up in the crack, while I tried to see it, and then to catch it with the left hand. It was very refractory, but came through at last, and I put my left arm through the loop. Meanwhile, however, there was time to examine the crack at my level, and I think that in it there is a small chock-stone, pretty far in, which might serve for a belay if it can be reached and if a rope will pass round it. I had no chance to try, but it is worth remembering, for if so it would be a great simplification and help at this part of the climb.

The loop belay settled, C.D.F. led up the Crack, and passed three loops over the chock-stone and under himself (see ” Novel Tactics on the Central Buttress,” Y.R.C.J., Vol. V., p. 16). I pulled on the loose end to his direction, but not quite to his satisfaction, for the rope sagged a bit, so that he said the loops were lower than on his former ascent. We then took off my belay, and I followed up the crack as quickly as possible, and on to and over my partner. After the long wait these few critical moments of te’nse excitement and rapid action passed quickly, and I do not really know what happened, except that I got off my partner’s head as soon as might be. I did not need my foot held, but do not know where it went. Probably being slimmer than former climbers, I got farther into the Crack and chimneyed it. I think I faced out, found a small hold for the right hand on the inside wall, and very quickly felt the top of the Flake. I said “I’ve got it ! ” and thrilled with the realisation that the thing was virtually done. There probably was not a happier woman in the world at that moment!

Astride the Flake, one found a good belay a few feet along it, pulled in the slack as the loops were taken off the chock-stone, and C.D.F. followed up very quickly. We both walked along the edge of the Flake, very cautiously, and balancing with both hands in the wall. Neither of us coiled any rope meanwhile ! Another upright piece of Flake follows (” dead easy “), and a much broader traverse, still going to the left and leading into the corner of broken rocks easily visible from below. Here C.D.F. took the lead again, and soon after we heard voices, and came into sight of two men on Keswick Brothers Climb, who asked with some interest what we were on. ” Central Buttress—just got up the Flake,” said C.D.F., with careful indifference, as his second appeared.

The traverses to the right again are certainly very thin indeed, especially the second one. The poor handholds and sloping footholds make it just about the limit, and demand most careful negotiation. There is nothing at all to put weight on, and the only method is a slow and cautious change of balance. Nor must the climber take any risk of a slip, for though the stances are good for the other man, I do not remember much belay here.

After that it was comparatively easy. There was a nice slab, and the climb finishes among several small slabs, sort of baby Botterills, of which we selected different ones. We forgot to note the time, but our supporting party at the lunch place said that in about 2,\hours we showed on the skyline, and we joined them again in 3 hours exactly, having come down Moss Ghyll (without help from Professor Collie, by the way ! ).

Unavoidably, no doubt, there has been a certain amount of criticism and talk of risk taken on this climb, so I am glad of this chance to say that no risk whatever was taken by either climber, but all rules of the game were most carefully and conscientiously observed. Had there been any risk, at any moment, I surely ought to know about it. Moreover, I can honestly say that at no point did I find that the climbing as such gave serious trouble. With fullest recognition of the fact that at every point C.D.F. was the real leader (whatever he may say about it), finding the route, coaching his second, and carrying through the really difficult engineering of the loops over the chock-stone ; what remained for me was a perfectly splendid climb throughout, compelling respect for it, and nowhere giving any excuse for carelessness or relaxed attention, yet nowhere either was my small reserve of muscular strength greatly taxed, nor had I ever that feeling of ” all out, and the pitch unjustifiable.”

I have had much more trouble on humbler climbs. There’s that top pitch of Walker’s Gully for example ! We did it some days later, and all went merrily, with the consequent lack of any detailed memory. At the top pitch we belayed carefully, both in the cave and on the wall, where a loop was duly threaded, but not used, for both climbed it by the backing-up method. This is recommended for tall climbers if I remember rightly, but being 5 feet 4 inches I found myself ” stretched ” rather literally ! The rope, or a knob of rock or both stuck into my back and hurt: it demanded real hard work, such as I hate, and in short, I was glad to get out of it! Then there is the new climb we did on Sgumain (Big Wall Gully we propose to call it), on the second day out after seven months off the rocks, and at the end of a rather weary time. The direct attack on the Gully looked wet and uninviting, so we climbed a pinnacle alongside, and traversed back into it. On the way we encountered a mantelshelf. C.D.F. led up it: I tried to follow. H. V. Hughes, who was third, could only see my boots from his stance. He says he went to sleep, woke up again, and they, were still there. However, they are not there now, nor is he, so we all got up somehow in the end, but it was not a star performance, except for the leader. Higher on the same climb there is a pitch leading by a thin but delightful traverse out of a cave, and then back at a higher level over a very narrow ledge, rather like the ” Cat Walk ” on Kern Knotts, only going to the right instead of left. I needed just rather more than moral support from the rope there : yet I am sure the climb would go, either by that or the alternate route taken by C.D.F., or perhaps straight from the cave. It is certainly a splendid climb, easily the best we did in Skye, where for the greater part of the time we ridge-walked ecstatically, unencumbered by rope.

For most severes dry rock and rubbers seem almost essential for one to get the whole joy out of it, to raise a good face-climb (which I love more than any gully or chimney) to the full ecstasy given by speedy movement with a good margin of safety. Therefore we proposed to spend a fine Sunday on the Pinnacle slabs. There was a distant rumble, but we judged that the threat had passed, donned rubbers, and started up the slabs from Deep Ghyll to Hopkinson’s Cairn. But it had rained the day before : the slabs were not perfectly dry, and one’s steps had to be chosen daintily, and with an avoidance of vegetation. Either I could not see the leader, or did not pay attention, and had not read the book of words, for I am told that I did not negotiate the Gangway according to rule, but walked along it upright, with extreme slowness and caution, and thinking it a pretty thin traverse. We had barely finished Herford’s Slab when, without warning, a deluge of rain descended. Soaked in a few moments, we retreated hastily round the corner by the bit of Girdle Traverse leading into Steep Ghyll. The rope belayed itself maddeningly round every point of rock. I stuck on the corner ledge, wet to the skin, in rubbers, longing for holds which did not exist; while C.D.F. sat in the Crevasse, a waterfall from Slingsby’s Chimney pouring down his neck, and told me depressing stories about that corner. Again some of my camping comrades had played audience, and when we joined them, not only had the rain stopped, but they had sheltered and were quite dry ! The rocks were not, nor were we,— camp as quickly as possible, and no more slabs that day.

It was hopelessly wet the last day of that summer’s holiday. But what then ? It was the last day, and could not be wasted. The Ennerdale face of Gable was near, and is nearly always wet anyway—an hour passed in Smugglers’ Chimney six years ago has impressed my mind. Engineers’ and the Oblique Chimney took some finding in thick mist, but when found we did them thoroughly, in boots, of course. We were not quite wet through in the Engineers’, and I enjoyed it; but by the time we got to the Oblique the rain had become heavier and the wind was cold. Soaked through, we went up it and down the Bottle-shaped Pinnacle with a sort of ” Well, that’s ticked off ” feeling, and were caught by the rest of the camp an hour later having tea at the farm (the only time that summer—honest!). Yet it was surely ” a good day of its kind ” as a Scotswoman said to us years ago, a party of youngsters setting off to cross from Glen Lyon to Killin in drenching rain. It is good to have done them under bad conditions, good to know oneself not only a fair-weather climber and friend of the fells. You cannot be that if you elect to camp at Seathwaite most Augusts !

” Blow, winds of Borrowdale and rains downfall:—

I would go to Borrowdale the last time of all.”