Lost Johns’ Cave

By Innes Foley.

In composing this tale of wanderings in Lost Johns’ Cave, the writer has been perplexed as to the proper course of action, whether baldly to describe the layout of the cave or give an account of each expedition in turn, whether to be geographical or to be human, and the narrative as finally written will, it is hoped, be such a compromise as will provide human interest without glossing over the technical details. The story is complicated, first by the long period over which the expeditions have been spread, and again by the amazing complexity of the passage systems.

I am well aware that experienced cave explorers will be pained at the immense time taken to achieve finality and at the slow and laborious nature of the assaults. To these I reply that this was the first cave of any size ever explored by the party, and to their inexperience was added the restraint of the conversation of local enthusiasts.

” There is nothing in Lost Johns’,” “It peters out quite soon,” and so on. All this tended to limit our outlook, and so at each assault to leave us faced with some strange and unexpected obstacle. There was no inkling that the cave went down to five hundred feet below the entrance and three quarters of a mile in distance. Moreover, the original members of the party were split up in a very remarkable fashion so that they could only meet on rare occasions. Thus P. F. Foley was at Nottingham and later at Epsom, Lipscomb in London, Kennedy at Devonport, Hicks in the Air Force at Chester, I. C. Foley at Newcastle, and so on. Gathering together was no easy business.

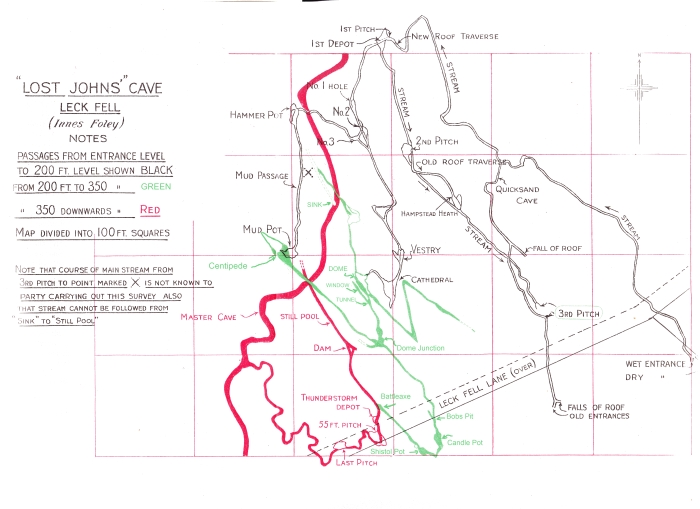

Many know the two entrances just over the wall at the top of the lane leading from Cowan Bridge up on to Leck Fell, and equally well known is the stream cave leading one hundred and thirty yards north-west to a small pitch where the course is altered to south-east. (There is a tributary branch on the left bank halfway in). Beyond the little pitch the cave leads on past another pitch till the big fall marked as “Pitch III.” on the map is reached. This fall is about a hundred feet deep. All this is common history, but it is apparently not well known that above the little Pitch I. there is a passage which leads to two other complete systems which eventually join up with the main stream some two hundred and fifty feet below. It is about these systems that the following paper is written.

lt was in September 1923 that the writer and his brother, Captain P. F. Foley of the Royal Engineers, first thought to explore the cave. With a candle or two and an electric torch and a length of Woolworth’s clothes-line they penetrated as far as Pitch II. Their tale inflamed the imaginations of the writer’s friends in Newcastle in after years, and in June 1926 a party consisting of George Hicks, J. R. Kennedy, Steve Mudge, and the writer, went over to have a try at it. After a try-out in the through passage from Rowten Pot to Jingle Pot, and a trip on the lake at White Scar they tackled Lost Johns’ with grossly insufficient lighting. A passion for overhead traversing led the writer to go aloft at Pitch I., and so the New Roof Traverse was found, but the show was brought to a sudden end by his mistaking No. 1 Hole, about fifteen feet deep, for a pool of water and nearly stepping into it. This hole was afterwards named “Innes’ Terror,” Terror becoming a general term describing any deep hole in the floor of an otherwise level passage.

The same party with P. F. Foley, Mrs. P. F. Foley and R. Lipscomb attached, but Kennedy away, attacked the Cave again in August 1926 and began by trying the branch at Quicksand Cave. It is hoped the reader will always have the map before him, as to describe the exact position of each name would make this tale too cumbersome. This was the old course of the stream and is blocked by falls of stone very near the surface. Mudge found a horrible little wet corkscrew passage in the roof of the Cave and, wriggling up it, discovered “Steve’s Grotto,” a little cave full of fine stalactites. A very narrow passage leads away from it, but it is full of falls of roof and has never been completely explored.

The party then proceeded to the New Overhead Traverse, passing over “Innes’ Terror” and over two more similar holes, Nos. 2 and 3, which had been dimly seen in June. The passage then began to drop and finished up in “Hammer Pot,” our first dry Pot and though only fifteen feet deep, something of an obstacle. The rope or ladder anchorage is queer, as it is necessary to belay either to a small peg of stalactite right up under the roof or to go some distance back up the passage. P. F. Foley and Lipscomb were lowered down and went along the Mud Passage. This drops very steeply and is floored with abysmal mud, but there are fine stalactites and the roof is high overhead. They were stopped by the thirty-five foot drop of Mud Pot and shortage of rope.

On the way back the writer persuaded the party to lower him down No. 3 hole. Here he found a tiny passage which dropped into a larger but still very narrow one which, leading back, joined up Nos. 1 and 2 holes. Hicks and Mudge followed the writer and turning down the new passage away from the holes found it to drop sharply and to increase in width and height until the climbable pitch of about ten feet into the “Vestry” was reached. This is a circular chamber with the usual conical roof, and there is a crack across the floor, widening and deepening at the far end. Then ensued perhaps the most crazy exploit of the whole affair, for Hicks and Mudge followed the crack down without ropes till it opened out into the “Cathedral,” a pot which is some seventy-five feet deep from the Vestry. The crack goes down in a series of steps to the Pulpit about thirty-five feet below, a long ledge running along one side of the pot. The name Cathedral will explain more graphically than any description what the place looked to our uninitiated eyes. The evacuation was not so easy, for though Hicks climbed out unassisted, when Mudge’s turn came, and the writer, jammed without foothold in the crack above, threw him a line, he contrived to lash himself to the ledge on which he stood, and for a long time all that we above could see of his struggles was one hand groping out of the gloom.

The descent of the crack into the Cathedral requires a rope or ladder, which may be made fast to a big yellow stalactite pillar on the left side in the narrowest part of the crack. This ladder should reach to the Pulpit, where a second ladder is needed for the forty feet sheer drop. For lowering ladders, tackle etc., there is a series of very fine footholds leading out from the top ladder anchorage to the outer edge of the crack vertically above the Pulpit, where a clean lift may be obtained straight from the floor of the Cathedral. To a rock climber there is an interesting little problem in the possibility of climbing out of the Cathedral without a rope. On the far side from the Crypt there is an annexe in which it is possible to climb to a level with the Pulpit, finishing up on a ledge a few feet from the last fragments of the Pulpit ledge. The crossing of these few feet might prove quite amusing.

The discovery of the Mud Pot and descent of part of the Cathedral gave us some idea of the possibilities of the cave, and during the winter there was much speculation about its course. The general opinion was that one or other of the passages led to Gavel Pot some half mile away down the fell side, and it was determined to make a really big effort at Easter to go right through.

At Easter 1927 the party consisted of Hicks, Lipscomb, Jack Kennedy, Alec Kennedy, Mrs. and P. F. Foley, Stephen Arthur and the writer. Mudge was ill and did not again join in until April 1929. A large number of ropes were brought and some time was spent in exploring the passages of Gavel Pot. When the party did enter Lost Johns’ Cave, P. F. Foley, Jack Kennedy and the writer carried out a prismatic compass survey of the known portion of the Cave while the remainder went down the stream passage. Following the old going aloft policy Lipscomb traversed over Pitch II., a most intriguing business, and found the Old Roof Traverse which leads to “Hampstead Heath,” where there is a sort of slide and a lot of broken glass. Here there is a short dry pitch down which Alec Kennedy was lowered. The stream was rejoined immediately after, and the party pushed on down the narrow main passage, dropping sharply all the time, till they were held up by Pitch III., the stream being in half flood and running very deep.

Next the Mud Passage was tried, and Lost Johns’ dealt us out with dramatic suddenness another of the surprises which seemed to come with such regularity. Following the idea that people who led on each new passage should follow it to the end, P. F. Foley and Lipscomb were lowered down the Mud Pot, which is a tube of about ten feet diameter and about seventy feet from roof to floor, though the pitch is only thirty five feet deep. The floor is cup shaped and filled knee-deep with mud, while a narrow passage leads away a few feet. P. F. Foley followed this up and promptly remarked that he had found another pitch and wanted the small plumbline. This was sent down, only for another request to be made for the long plumbline. The hole turned out to be ninety-four feet deep, and the edge of it was as sharp as a doorstep. It is a very wide, awe-inspiring place, and a continual dribble of mud splashes on the black rocks below. As it was nearly a hundred feet deep and very horrible we named this place “The Centipede.”

That night the survey was plotted out, and the surprising turns and twists of the cave realised for the first time. The plotting was actually, afterwards, done on the ground, and the absurdly small space covered was painfully noticeable. The Quicksand Cave was only surveyed in the early, wet and uncomfortable morning after the first map was plotted, and when the positions of the first falls of roof were plotted on the ground they were found to coincide exactly with some half blocked holes in the ground at the end of a long depression, obviously an old stream bed.

After the Easter show it became quite obvious that we could get no further without rope ladders, and we set to work to acquire these. Lipscomb evolved a very neat design with hollow bamboo rungs through which both ropes passed, ensuring safety in the event of the breaking of a rung. It was very light and delightful to handle as there were no projecting rung ends to catch on rocks, but being the first of its kind it was an awful brute to climb owing to the wide spacing of the rungs. P. F. Foley also acquired an immense ladder sixty feet long and heavy as lead. With these and another shorter one the party assaulted the cave in August 1927.

This time Hicks, Lipscomb, Mrs. and P. F. Foley and the writer were left of the previous crowd, while C. E. J. Dingle and S. T. Waite were new to the game. The last, a geologist, proved very useful, but as all his notes were lost and he himself is in the jungles of Borneo none of his information is included in this chronicle. Our first attempt was on the Cathedral, where much delay was caused by the writer getting hopelessly entangled in coils of ladder at the Pulpit. He eventually attached Lipscomb’s ladder to P. F. Foley’s all crooked. The discovery of this when swinging for the first time in the darkness induced a condition bordering on panic, and he came up again. Eventually Hicks and P. F. Foley went down, and Hicks reported it no good, chiefly owing to the narrowness of the passage which is now known as the “Crypt.” The Crypt afterwards turned out to lead to the “Dome,” a seventy foot pot which provides by far the easier way down to the lower part of the cave.

As it was, the party turned back and next day had a look at the main cave, but again baulked at the hundred foot fall of Pitch III. It was almost decided to go home, but mercifully we remembered the Centipede and attacked it instead.

In those days we were still exceedingly cautious on ladders, employing a life-line even on the Mud Pot. P. F. Foley remained at the top of this while Hicks, Lipscomb, Mrs. Foley, Dingle and the writer went down. All the ladders were lowered to them and made fast to an anchorage at the back of the pot. After a considerable amount of argument Hicks and Dingle were lowered into the blackness, while the other three waited in the Mud Pot, soaked in mud and bitter cold. Here it may be mentioned that the Centipede, being our first really deep pot, seems to have inspired us with a peculiar horror which in the future cramped our movements not a little. The vast size, the overhang of the ladder face, the incredible sharpness of the edge at the end of the connecting passage, and the continual dripping of the mud, all combined to make the place more loathsome. The actual ladder pitch is seventy three feet to a ledge, and the overhang is such that after the first ten feet the ladder does not again touch the rock till the ledge is reached. The descent to the rift passage at the bottom is quite ordinary climbing. Incidentally, there is a passage leading away at ledge level over the top of the main bottom exit passage, but it is too narrow to follow. There was also another passage which the party noticed at a later date entering the Pot some fifty feet from the floor on the left side looking from the Mud Pot. This may be marked by its proximity to a remarkable stalactite formation like an octopus with tentacles dangling, and it would seem to be possible for determined climbers to reach within a few feet of it up some stalactite steps from the ledge.

Dingle and Hicks were away two hours. They reported having followed a continually dropping passage to a big junction. Turning to the right they went along a very narrow high passage and passed over a hole in the floor, afterwards called Bob’s Pit, which was explored by Hicks and the writer in August, 1929. [The Pit was found to be twenty-two feet deep and an impossibly narrow passage led away, the walls coated in the most disgusting slime the writer has ever encountered.]

Hicks and Dingle carried on until they were held up by the sixteen foot sheer pitch of Candle Pot, in a part of the cave remarkable for the strange rock formations. They could hear water roaring quite near and they imagined that they must have hit off the main stream again near Pitch III.

On their return they helped each other up the two ten feet pitches of the other branch at Dome Junction and reported having looked out into a big pot. The formation here is very queer. A few feet from the top of the upper pitch a narrow tunnel branches away to the right, an unpleasant, jagged flat crawl ending in a deep rift. Further on past the tunnel the passage becomes higher and in the right side, some six feet off the ground, is a complete window. Climbing up into this embrasure Hicks and Dingle looked out into the blackness of the pot which was afterwards called the “ Dome.” The bottom, a rift passage, was some twenty-five feet below and the top some fifty feet overhead. They did not, however, descend, and it was left to a Y.R.C. party led by Mr. E. E. Roberts next Whitsuntide to make the first crawl through the tunnel into the bottom of the Dome.

Hicks and Dingle then returned to the Centipede, where the watchers gladly dragged them up, after which there ensued a fearful struggle with the big ladder, which was finally dragged into the starlight at 11 p.m., the party having been eleven hours underground.

Again there ensued a winter of argument and speculation. It was generally agreed that the water heard was the main stream, but where was it? The idea that the cave led to Gavel Pot cropped up again with the change in direction, for it had been imagined since the plotting of the survey to Pitch III., that the main stream continued in a southerly direction, following the line of the valley which runs along the side of the Leck Fell Lane. In order to facilitate the descent of the Centipede, Hicks, Dingle and the writer visited the cave on December 17th, 1927, measuring up the Mud Pot for safety tackle, and Lipscomb evolved his famous counterbalance gear by which the life-line passed over one sheave of a double block at the top of the pitch, back to a single block at the ladder anchorage and so over the second sheave to a bag suitably filled with mud. The haulage party had then only to overcome friction losses, and the writer can testify that the ascent was a speedy business at Easter, so swift indeed that he missed most of the rungs with his feet as he shot heavenwards. This gear of course was only necessary in this particular instance, where the great depth was a trial to a tired man and where it was impossible for a haulage party to find a decent stance close to the edge of the pitch.

At Easter 1928 only Hicks, Lipscomb, the writer and R. Stephens were available. The last named was a brother officer of Hicks in the R.A.F., and though it was his first cave he achieved considerable glory by his tenacity of purpose. He strained a foot severely the first day, but though in considerable pain he insisted on coming in to help, taking a useful part in the evacuation of the ladders in record time.

The ladders and counterbalance gear were installed on Friday, and on Saturday Hicks and Lipscomb descended and pushed on past the limit of the previous August, Candle Pot. The pitch is easy with a good ladder anchorage. The next obstacle was Shistol Pot, a nasty wet little ten foot pitch with at that time the most hair-raising anchorage any party was ever foolish enough to use. Later on the Y.R.C. used a very startling “bayonet ” of rock some yards back up the cave. At this point there is an abrupt change of course from south-east to north-west, and soon afterwards the party reached the stream at a point which they named the “Battleaxe,” from a very curious knife edge of rock on the side of the cave. There is no chamber here; the dry passage running north-west just ends in the narrow stream passage running south-east, the water being some thirty five feet below, Climbing down by short ladder and a rope, Hicks and pushed upstream, since their progress downstream was immediately checked by a ten foot pitch, quickly followed by another pitch of unknown depth. Upstream the passage is very narrow and quite clear of stones till a very remarkable check is reached at the point marked “Dam.” Here there is a big buttress on the right bank of the stream with a little tunnel for the water, while a dry by-pass goes round, floored with a conglomerate of stones and sand. There is a hole in the roof here which is thought to have some connection with Bob’s Pit. From here upwards the stream is one long pool which slowly increases in depth, while the roof which descends abruptly at the Dam, becomes lower and lower. The party ploughed through the pool for about sixty feet and eventually turned back when the roof, which was very soft and treacherous, was about a foot above the water.

Very little was done in this expedition. On Sunday night Hicks and the writer visited the Pool again, afterwards revisiting the Dome Window, where they noted a passage coming in at the top of the pot. It was afterwards regretted that nervousness about the Centipede and a knowledge of the arduous task awaiting such a small party in evacuating the ladders prevented them from entering the Dome. Ladders were left fixed in position on the climb from Dome junction and a depot of bully and candles was established at the Centipede.

It was during this assault that the principle of the “out-by party” was instituted, which was employed on all future expeditions. It was arranged that the men left at the top of the Centipede went right out of the cave altogether, returning fit and fresh at stated times to haul the “in-by ” party out. In this way the “in-by ” or exploring party were not cramped by the thought of the poor souls waiting in misery above, while the “out-by ” party were to carry out the odd jobs necessary in camping.

The survey carried out enabled the position of the Dome to be fixed, and it was noticed that the passage at the top of it came very near the Cathedral. It therefore afforded no little satisfaction when a party from Manchester led by J. R. Kennedy visited the Cathedral during May 1928 and surveyed the Crypt passage, the end of their survey corresponding exactly with the top of the Dome. They did not, however, verify that it was the Dome.

At Whitsuntide, 1928, five of the Y.R.C. led by Mr. E. E. Roberts descended the Centipede, climbed through the Dome Tunnel and descended into the rift at the bottom for the first time. This rift is continued in a passage leading sixty feet due north, ending in a double pitch of five and ten feet. The chamber at this point has apparently been formed by the removal of a remarkable bed of shale some four feet thick, the water afterwards scooping out a narrow channel in the limestone floor, leaving a wide flat ledge on each side. The flat ledges continue at roof level but the narrow channel ends in a forty foot pitch to the main stream. Mr. Roberts’ party descended to the stream which was running north-west to south-east, but were stopped downstream by a complete dead end in a pool of stones, while progress upstream was barred by a twenty foot pitch. Here it may be mentioned that at Easter 1929 Lipscomb, Hicks and the writer tried to circumvent this pitch by traversing over on the roof level ledges aforementioned, but they were stopped by the shelving of the rock some twenty feet beyond the forty foot pitch. This party never descended the forty foot pitch, but from Mr. Roberts’ survey readings it was found that the sink which he found was quite close to the long still pool which stopped Hicks and Lipscomb in their upstream progress from the Battleaxe at Easter 1928.

The Y.R.C. party also went down to the Battleaxe, descended the little ten foot pitch and the following pitch, which proved to be fifty-five feet deep, afterwards following a narrow winding passage to a pitch which they could not descend for lack of ladders, though they reported it to be quite small.

At August Bank Holiday, 1928, the next assault was made and it was determined to try to get through from the Cathedral to the Dome. In a preliminary week-end the hole at the end of the Crypt passage was descended and after a little doubt was proved to be the Dome, the depth being seventy feet with sixty feet of ladder pitch. This is much the easiest way down to the lower parts of the cave, being dry all the way and the only difficulty the annoying scramble through the tunnel.

This attack was an extremely dramatic affair. We knew we were near the end, for we knew the limestone to be at the most six hundred feet thick while the Y.R.C. limit at Whitsuntide was four hundred and fifty feet below cave entrance. Mr. Roberts had prophesied another pitch followed by a long passage ending in a sink, and whatever the true nature of the end the party were full of excitement at the prospect. The exploration began with a side show when Lipscomb, Dingle, Sale and the writer took the ladders down during a preliminary week-end, and by way of exercise tackled the very narrow passage leading out of the Dome on the opposite side to the Shale Cavern. The passage leads about sixty feet south-east, seventy feet due north and eighty feet south-east with remarkably sharp corners. However, at the end the passage becomes too narrow for any but small and very determined children, which is much to be regretted, as the sound of falling water is very clear and the narrow place is by the map only seventy feet from Pitch III. R. Lipscomb tried it after the Y.R.C. had reported failure, but he could make no progress and later on Hicks and the writer tried, but only succeeded in getting a few feet further by climbing up to the roof.

On the first day of Bank Holiday week-end the following arrived and promptly dropped a ladder down the fifty-five foot pitch below the Battleaxe:- P. F. Foley and Mrs. Foley, Dingle, Hicks, Lipscomb, Sale and R. Wilson — the writer joined the party after this hard work was done. The ladder work at the Battleaxe is queer and a small dissertation may be useful. First a short ladder is necessary, hung on the opposite wall of the stream cave and reaching down to the first ledge. Then it is best to walk up the ledge and drop a ladder or lashing to the stream, thus at the same time avoiding a nasty little dribble of water from the roof and providing by means of the bottom of the rope or ladder a handhold with which to surmount a surprisingly awkward little slope of rock on the way up to the Dam. A rope is sufficient for the ten foot pitch while there is a splendid ladder anchorage for the fifty foot pitch which, barring the depressing effect of the torrent of water on the climber’s head, is an easy climb owing to a slight slope on the rock face. The little round chamber between the ten foot and fifty-five foot pitches is so drenched with spray from a projecting seam of shale under the fall that we called it “Thunderstorm Depot,” and any wretch who is forced to stay there any length of time is earnestly advised to climb on to a big ledge some feet overhead where it is dry and comfortable.

At the foot of the fifty-five foot pitch is a narrow, serpentine passage which winds about in the floor of what appears to be a single immense cave. We have never ascertained the upper limits of this pot, which appears to continue to Last Pitch, and all we know is that from below the fifty-five foot pitch and at Last Pitch we could see unfathomable depths of gloom all round, from which projected buttresses of rock stretching up into the darkness overhead.

At Last Pitch, the limit of the Y.R.C. exploration, the stream falls through a narrow opening twenty feet into a large round pool of uncertain depth. On the right side, however, is a dry by-pass leading to a ladder pitch of twenty-seven feet on to the shingle bank at the side of the pool.

So matters stood on the Sunday morning of August 1928 when, leaving Captain and Mrs. P. F. Foley as “out-by” party and the writer at Thunderstorm Depot, a party comprising Lipscomb, Hicks, Dingle, Sale and Wilson pushed on into the unknown. The passage continued from Last Pitch, winding and looping for some hundreds of feet on a westerly course and then debouched, not into another pitch, not into a sink, but into a master cave which dwarfed all the passages yet encountered. Running due north and south, ten clear feet in width and anything up to a hundred feet high, this cave, of which Lost Johns’ is but a tributary, appears to run along the bottom of the limestone, gathering the water from each small cave in turn. The stream flows rapidly over a pebble bed, cutting deep under the rock at each corner and leaving banks of a sort of concrete of mud and black pebbles. The walls of the cave are not of clean bright rock, but are coated with the mud and grime of ages.

The party turned north or right-handed at the junction and for three hundred yards or so proceeded in moderate comfort along the wide cave. Then the stream ceased to flow, and the pools became gradually neck deep, while the roof of the cave descended till there was only six inches of clearance above the water.

Ploughing through knee-deep mud and nearly out of their depths in water, the party were glad when the roof receded, and the pools became more shallow. At about four hundred yards a large stream came in overhead which was thought to be that from Gavel Pot. And so the party splashed on. The compass was waterlogged, so that no idea could be got of direction, and the poor souls could only press ahead, hoping that the ordeal would soon come to an end. Another narrow place was passed where quite a moderate rise of water would be sufficient to bring the level up to the roof, and at last some thirteen hundred yards from Last Pitch the roof again shelved until it disappeared under water. This point must necessarily be the end of Lost johns’ since the assault was carried out at the end of a long spell of fine weather, and it is unlikely that that the water level would ever be lower. The first three hundred yards of the Master Cave have since been surveyed, showing a northerly course, and a continuation of this course plotted on a six inch map brings the end no great distance from Easegill Kirk, where, near the Witches’ Cave, there is a great rising.

When the water of the Master Cave touched the roof our party had done their work and turned homeward, plodding wearily and hopelessly along. The writer gathered that none of them expected ever again to see the light of day, but that they thought they might as well go on as stay, so on they went, counting the paces and only stopping to rescue Dingle who was seized with cramp. At last the writer on his ledge at Thunderstorm Depot heard voices mingling with the roar of the water, voices raised in a ribald song. A joyful shout ; down went the lifeline, and soon the five soaked adventurers were once again at the Battleaxe, safe, if somewhat surprised at their safety.

Most of the party were too wearied to take much interest in caves on the Monday, so the ladders were left in place for three weeks till they were evacuated by a party consisting of Hicks, Lipscomb, Dingle, Sale, Gowing, D. Reid and the writer. Besides the ladders all stores of candles and food were also removed, and during a quiet interval Hicks and the writer explored Bob’s Pit. This party also tried the narrow passage which seems to run from the ledge of the Centipede to Dome Junction, but they could not get far. The junction end of this passage is fairly obvious among the jumble of weird rocks on the opposite side to the Dome.

At this time there was a mistaken idea that the party had finished the cave, but as the horror of that trip through the mud wore off, the memory of the other branch of the master cave at Groundsheet Junction became clearer and quite oppressive, until it was definitely decided to continue the exploration. Lipscomb was convinced that the biggest stream dropping into the master cave was that from Gavel Pot, and he insisted that this would be a better start for the assault than Lost Johns’ as it was a hundred feet lower down the fell side. We were assured by Mr. Roberts that Gavel Pot was a dead end at the bottom of a seventy-foot shaft, but it was decided to have a shot at it. A party in December did not get very far, Lipscomb reporting from near the bottom of the shaft that it was no good.

At Easter 1929 an assault was made which, though not as complete as was desirable, finished off the lower parts of the cave. It was a very leisurely show, carried out with due regard for comfort. The weather was fine and it was a glorious night when the party gathered on Thursday, March 28th. There were nine men this time, and it was noted that for the first time the original four who began the show were together again ; Hicks, J. R. Kennedy, Mudge and the writer. There were also Lipscomb, Dingle, E. K. Scott and R. D. Crofton from Kennedy’s Manchester party and J. Markby, a New Zealander and friend of Hicks in the R.A.F. On Friday the party took the ladders down as far as the fifty-five foot pitch, while Lipscomb and Dingle arranged a sandbag dam at the point marked “Dam ” on the map. Hardened cave explorers will probably scoff at this, but it has always been our endeavour while getting ahead as far as possible to do so with the maximum of comfort. Lost Johns’ Cave, with the exception of the Centipede route, is very luxurious, and it was pleasant to be able to go down to the Master Cave comparatively dry. The Dam, like the counterbalance gear at the Centipede, was the product of Lipscomb’s imagination, and proved a wonderful help, since, being at the end of a long pool, it took half an hour to fill, allowing the whole party to go up or down the fifty-five foot pitch.

Next day Dingle, Markby and Mudge remained as “out-by ” party, the last having done very well the previous day in reaching the Battleaxe with a helpless leg. The rest of the party went on, leaving Lipscomb to work the Dam. Kennedy, Scott and Hicks were a survey party and surveyed from Fifty-five foot Pitch, past Groundsheet Junction to a point some three hundred yards along the Master Cave, while Crofton and the writer went ahead, turned left at Groundsheet and entered the unknown part of the cave which kept a steady general course due south. The great width made the going very easy, it being possible to walk along the hard shingle banks without touching the stream. At fifty yards and again at a hundred there were big branch caves coming in at a considerable height, the flow of lime from the second one being a very fine sight. It came rolling down in great waves, finally forming a complete bridge across the cave, An attempt was made to climb up here, but the black mud with which everything was coated made the holds so treacherous that no progress was made.

Beyond this point the writer’s recollections are vague, as no notes were made of the sequence of the features of the cave, rocks from the roof lay about in ever greater profusion, at one point a huge block ten feet high completely filling the passage. At about two hundred and fifty yards there was a very surprising change, for the ninety foot high roof suddenly descended until there was only a little round chamber not ten feet in height, from which the only outlet was a circular tunnel, along which it was necessary to creep on hands and knees. This tunnel lasted thirty feet or so until the cave opened out larger than before, but with the falls of roof even more frequent, more recent looking and more terrifying. Then at last at three hundred yards the end came when the party were brought up by a tremendous fall, towering up to the roof, rock on rock and piece on piece. The broken rocks looked yellow and freshly broken, and the nearest pieces moved when touched, but there was just one passage on, a tiny aperture under the overhang of the wall on the left hand side. A torch beam showed that this passage was blocked some distance further on, but it has always been a matter of self reproach to the writer that he did not climb in and verify by actual touch that there was no possible way through. [He has done since — Ed.].

That was the end of the exploration of Lost Johns’ Cave, and it will be seen that there are still riddles and problems to be solved. The writer doubts whether the Master Cave can be traced any further either way, but even if no further progress is made, the Master Cave is a sufficiently remarkable spot to justify a visit, and the whole cave, barring always the Centipede route, is of such a comfortable nature with its high passages and its continual dryness and cleanliness that the least enthusiastic of cave explorers may conceive an affection for it.

In conclusion, it is well to point out the main question which has never been solved by the parties which carried out the work described in this paper. We have never been down Pitch III. on the main stream, and though we know this has been descended we have never seen any plan showing the lead of the cave beyond. Moreover, no one has climbed the twenty foot pitch which baulked the Y.R.C. party when they reached the main stream, from the Dome. To any enterprising explorer, therefore, there is this one final problem, definitely to map the lead of the main stream from Pitch III. to the block below the Dome.

[Knowledge of the story of the two lost Johns, and the evidence of the books which mention the cave, have compelled the Editor to revise his grammar and adopt a plural form.]