A Trek In Northern Rhodesia

By E. J. Woodman

After the continued strain of being a Yorkshire Rambler for a short period, and to recovei from the effects of pot-holing, I was told to clear off to a warm climate. South Africa had long been very attractive to me, so I decided to go there, with no plans, being unable to find anyone to accompany me. I resolved to stay for at least a month in the Cape Peninsula to get the benefit of the climate, but after that to let things take their own course. Lack of funds prohibited a trip to the Drakensberg or into Central Africa to the Ruwenzori (which has always had a fascination for me).

On the 29th November, 1928, I sailed from Tilbury in S.S. Gloucester Castle, a small 8,000 ton boat, and after an exceedingly pleasant voyage reached Cape Town in 22 days. Early on the 22nd day I got up to see the view of Table Mountain. A sheer cliff rising out of the morning mist greeted us. As the cloud shifted, we got a marvellous view of the town nestling beneath its imposing background.

Cape Town is an interesting place, being a very old settlement, while the mixture of Dutch and modern English styles, in architecture and farming, is a source of endless marvels in the Cape Peninsula. Having to spend considerable time in Cape Town for other reasons, I decided to stay out in the Peninsula so that I could get into town any time required. I decided on Kommetje, and put up at a small hotel for £3 a week. In a fortnight my old motor cycle arrived from England and I proceeded to explore.

The Peninsula was delightful, the mountains of the Table Bay group being all around, 2700-3,000 feet, bare dry rock warmed by a sub-tropical sun. I met Dr. Barnard of the South African Mountain Club and spent an enjoyable day scrambling about with him, and putting in a good walk as well. (Temp, about 100-1100 in the shade). The heat does not affect one much, so dry and invigorating is the atmosphere.

Eventually I regained strength and decided to get further afield. The old motor cycle I exchanged for a car, loaded up, and away into the distance.

The mountains rise up in about 50 miles from the coast. I got through the first belt, spending a few days in the first range near Bains Kloof, and proceeded to Ceres. Here I met a young South African who was needing a change and took him off on tour to the South Coast. Every night we slept in the open, often not bothering to put up a tent. The nights on the veldt were wonderful, clear, starlit, and with a blazing fire of veldt bushes one is soon comfortable. (There are no trees on the veldt, except thorns and few even of them).

My people being due out for two months I returned to Cape Town to meet them on February 25th, 1929. Going up one of the passes a native chauffeur got the wind up, and as I was going down crashed into me and finished the Morris. My camera was useful, I took a few exposures, went into Cape Town on a goods train, and met my people, thus appearing in the Mount Nelson Hotel generally dishevelled and dusty straight off the veldt. The other fellow’s insurance company paid for the damage and I sold the remains, and like a good Yorkshireman made all costs, as I had got a good price for the motor cycle.

My people decided to tour the country by car, doing r4o-i5o miles a day, stopping in hotels en route. I wanted to get the benefit of the open air, so took a railway ticket to Bulawayo and arranged to meet them at the Victoria Falls on the Zambesi. I spent a few days shooting with a friend I had met whilst in the Cape, and then left for Livingstone, on the north bank of the Zambesi, where eventually I got a native servant who said he could cook !

We managed to get a lift on a timber train and so got 70 miles out of Livingstone before I was due to go to the Falls and meet my people. Livingstone is in Northern Rhodesia, and the Falls Hotel in Southern Rhodesia, with only a railway bridge between and no motor traffic allowed. Porters, however, were seized upon and we duly arrived at the hotel and met again.

The Falls have been described many times, but no description can convey the majesty and grandeur, of clear blue sky, millions of gallons of water, narrow gorges, 300 feet of spray rising like a beacon visible for 80 miles around, wondrous, ever-changing, and everlasting rainbows, and all the colours of nature.

I made friends with a farmer whom my people had met, and was invited to go and see him 500 to 600 miles further north. Needless to say I went, arrived at a station, dumped everything, and chartered a Ford from the local magnates. Twenty-five to thirty miles does not seem much at home, but with large tents, food, clothing and necessities, in the tropics it is a long way. The Ford solved it, and after going along a fine road for two miles, we got on to the main Great East Road. The road, however, does not live up to its name, being a narrow track with marks where the wheels go, and one in the middle for the oxen ; grass up to 8 or 9 feet high on either side. It serves, however, the main purpose of roads in Rhodesia, to give one a line to follow, although at times even this vestige of a track is apt to give out. We arrived, however, after much bumping and losing our way.

The farm proved very attractive, three round wattle huts, very cool under the hot sun and exceedingly clean and airy at night. The natives do not understand how to build straight and even a white man cannot make them, so every hut is round. The height there was 5,000 ft. and the country hilly, the hills rising up 1,000 ft. above the general level, densely wooded (for Southern Africa) and dry as a bone. It amazes one to see trees existing through six’months of drought.

The country had only been settled round here for about 15 years, and the farmers were troubled by a good deal of wild game. Snakes were quite common, but round the farmhouses all the ground had been cleared and the owner’s young daughter, about 9 years old, was told to keep within the clearing unless accompanied. One evening when the natives were clearing the bush away I saw a yellow body flash across from one side to another, and hastily fetched a gun and spent nearly half an hour trying to find the reptile. After a while one gets quite callous and unheeding with snakes, so I poked about in the various bushes—knowing it was a puff adder. Next morning, when the niggers were at work, they suddenly jumped back, and there, where my feet must have been about an inch away the previous night, was a large puff adder, which was finished off with a spade by

Mr. Shaw Kyd. The average native in these parts will not go near any snake, dead or alive, and it is left to the white men to kiU them off.

The farm surroundings were glorious, clear sunrises in a chilly morning, the ” Morning Glory,” a blue convolvulus, opening up all round, and just a nice cool nip in the air. The sunsets in N. Rhodesia are an everlasting delight and glory—the distant mountains taking on all the hues of the rainbow, and the sky one mass of colour. One goes to bed with the certainty of another morning more or less like the last.

After a few days on the farm I managed to raise four oxen and a ” Scotch cart ” with the intention of setting off into the blue, but this time unaccompanied by any white man. We duly assembled all the kit, consisting of ” scoff ” box with Hour, bacon, jam, a few tomatoes, onions (being the only vegetable that keeps) and potatoes. The natives are largely ignorant of vegetables and do not grow them. Bread is baked with hops and sugar in water. One just fills a bottle with water, adds sugar, and a pinch of dried hops, and beholds next morning, yeast (or rather a solution of it). This bottle is most vital and one looks after it carefully.

I had engaged an ugly looking nigger who had been with white men before. He had been christened ” Jam ” (no doubt on account of his liking for this scarce commodity). Mr. Shaw Kyd’s cook, Kalemba, also accompanied me, along with another boy, Kai, and a piccannin. We started off at 4 p.m., loaded up with bath, tent, etc., and the first night got to an outlying cattle ranch. Here I was most kindly received and had a meal and slept the night in my tent. I understood the owner had lost four cattle that season to lions, so things looked cheerful.

Next morning we pushed on into native territory, and at midday slept under a wild fig tree. The grass, now we had got away from settlement, was anything up to seven feet high, and in the short patches the seeds penetrated one’s stockings and delved into the flesh ; they are barbed and work in everywhere. As a protection I had started wearing a pair of climbing boots and leggings, but soon gave them up for bare legs, no socks, and canvas shoes. The hard baked veldt is no place for nailed boots. We arrived towards sundown at the Chongwe river and found it impossible to cross, as the banks were too steep.

I had been warned not to take the oxen over the river, mainly because of the tsetse fly (which is more or less fatal) and also because of having to build thorn fences against lions every night. I therefore sent Kai back with them and pushed on to the village about half a mile across the river, getting porters from the village. This process needed a lot of persuasion, but I put iodine on the sores of the headman, and so made a friend of him for life.

Here Kalemba, my borrowed cook (and everything else), had to leave and go back, and I found ” Jam ” had very little knowledge of English, amounting to adjectives, plus go— come—big—small—beast—dog—lion—buck, etc., and this was all. My first attempts at bread making were not a marvel, but I improved bit by bit. Game was scarce, so my flour was being used up ! A raw heathen native came along desiring a job as porter, and meat and salt, so I took him on, and christened him ” Joseph ” as he arrived with a goat. (The goat he returned).

After getting a few porters (a difficult job, as the men were mostly away working on roads and mines up in the north) I moved on to the chief of the district’s town, Wunda-unda. Milk and eggs could be got here with a little luck. Eggs are apt to be too mature, the natives not understanding the use of them except for rearing chickens.

Here I managed to get a few small buck in the short grass in the woods. In the valleys and flats the grass was eight to ten feet high and one could see nothing. We happened to strike fresh tracks of lion but after following them for a bit, lost them in hard ground. (This was lucky, as it was a foolish thing to do). I had reasoned, however, that if ” Jam ” and ” Joseph ” armed with spears only were game, I, with a high power rifle, ought to be ! Also ” Jam ” had my gun loaded with solid ball in one barrel.

I now had trouble with ” Jam “—he wanted to move off to his village with the rest, but by the threat of putting on my boots (now relegated to being carried in the bath) he became somewhat tractable.

Round here the hills were covered with trees and short grass, but game was scarce and no bigger buck were to be seen. Every time I had a shot there was great excitement from Joseph, who had never seen a rifle before, and one’s accuracy of aim is not too good when a raw native, in order to see better, is waving his spear in the region of one’s neck and ears. Joseph turned out the best of the bunch.

We pushed on, covering about ten miles a day, towards ‘Chipongu, where the ground was supposed to be better and more hilly. The troop goes along, a native in front, self behind him with loaded rifle and a gun handy. The native in front is much quicker at seeing snakes than the white man ! The track is a narrow path only allowing one man at a time, through grass the usual six feet high ; here and there one comes across barer patches of sand with a few trees, largely mimosa, with business-like thorns, and some leguminous trees bearing large pods (also thorny). Flowers of many varieties are seen on the sandy soil, and some of great beauty. In the drier and more barren places one comes across the giant euphorbia, an ugly looking tree—cactus, full of acrid milky stuff.

The birds give out no song. The chief performer is the dove with which one gets eternally fed-up ; all the other small birds give out harsh discordant notes which jar on one’s ear. During the day insect life is not felt or seen, and a mosquito net keeps it out at night. (I was never much bothered with mosquitoes the whole time in Africa). Going along the track we came across fresh tracks of what one said was lion, another hyena, I thought most likely the latter. They were not very old, as they had not been disturbed, so the natives wished me to go in front with the rifle !

Camping in the evening at a village we pushed on, spending either the morning or after 4 p.m. trying to shoot small buck for meat. My flour was running very low and was only used now as little as possible. One soon gets tired of a meat diet. Onions were very useful, as they withstood the climate and formed vegetable food. Eventually I was reduced to mealies (maize meal), and Kaffir corn and monkey nuts, and much as was the fun of originating new farinaceous dishes, the palate and the stomach did not very much relish it ! The monkey nuts were the best stuff. Meat killed one day at 4 p.m. was no good to me the next evening. I only tried it once, and my head spun round and round, and so did everything I looked at. (Alcoholic drinks unobtainable—oh, for a Hill Inn !)

The natives are very primitive here—a Magistrate once or twice a year, boys back from labour, being about the only contacts with white people. Native agriculture was very like what it must have been in England before the time of the enclosures—a flat piece of land large enough to support the village being dug and planted, without walls or fences. In the daytime all the village is hoeing and frightening away the wild birds and animals, and at night a watchman or two in a small hut make a continual din. Plants must be fortunate to do without ears ! One can always hear a native cultivated patch, and smell the village not far off (at least in Rhodesia).

Water is carried in canvas bags which keep the water cool by evaporation from their damp surface. One fills them with boiling water which one boils one’s self, for the native will never boil water for drinking properly, as he does not understand the idea, though he will boil it properly to make tea for the white man !

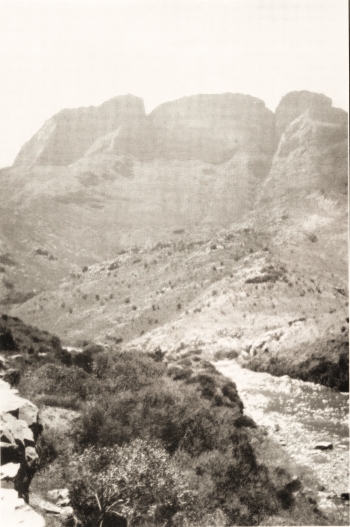

The hilly country was becoming more distinct. It was simply, however, caused by the lowering of the level of the plateau, as is often found in Africa. The hills were very dry and water was scarce and at good distances away. The views from the tops were wonderful; acres and acres of small valleys with grass and occasional trees, wonderful colours towards the setting sun, and in other directions 40 miles of plain with distant hills rising about 1,000 ft. above the plain. The country is one vast upland and at 4,000 ft. is quite healthy and cool, the nights being cold enough for one to sleep well and soundly.

Time being nearly up, I turned my face towards the railway and the Cape, via Mr. Shaw Kyd’s farm. Whilst there we caught a live iguana, which I should have liked to have brought back home. Imagine the astonishment of the local habitues of the ” Falcon ” at Arncliffe, to see such a beast running about the ” pub ” floor ! It would have been worth many pints of Tetley’s best !

Five nights and four days brought me back to Cape Town ; never was human being so glad as I of the food on the train, and at the farm, particularly the small bottles of South African wine, while to get the fruits of the Cape again was a great event.

I travelled home first class by a slow boat, excellent in every way, for £40. The total cost of my whole trip from England and back home was £220-^225 plus an old motor cycle worth at home, £30-^35 with luck ! This cost included buying and selling a motor car, doing 2,000-4,000 miles on it, and a £30-35 railway fare. As I was not in the best of health when I went out I had to be careful, and so had to live in a civilized manner for a month or a month and a half, and at expensive hotels for nearly four weeks.

From my experiences I now think it would be possible to get out there for, say, £40 fare—make it £55 with sundries ; that is £110 return first class by a good boat. Once there, stay about a week at hotels and the remainder of the time in the open, trekking from place to place at the cost of one’s food for the day, which in Africa is almost negligible, if one cares to make it so, and need not amount to very much if one wants the best one can get. Enough fruit (in season) can be bought in the country for less than fourpence to feed one for the day. Out in the lesser known districts and countries, Rhodesia, etc., if one had some form of transport one could make a profit easily in the harvest time by taking produce to the town or railway line. Transport is the whole key to African development.

When the rain comes down on one’s tent roof, when the grass without is soggy, when my tent mate comes in with heavy boots covered with mud after a wet day at the winch—Fell Beck in flood—only the shouts, and the smell of Percy’s good roast beef and Yorkshire pudding drive one’s thoughts from those evenings spent in cooking an evening meal, under a sky of flaming colours, as the stars come out in glory and the smoke of one’s fire rises straight from the silent and limitless veldt.