In The Adamello And Brenta Groups

By E. H. Sale

Some time early in the summer of 1931 I got a postcard which said : ” Join me in the Adamello and Brenta districts in August.” A suspicion that the names referred to mountains somewhere in the Alps was confirmed, and some subconscious premonition of the fall of the pound prompted me to say ” yes ” and to use my remaining fortnight’s holiday before Mr. Snowden became really active.

Carrying a lot of maps, guide books, and tobacco, I met Binnie at Brigue on August 15th and listened to a tale of woe about the weather in the Oberland during the past fortnight. Binnie’s spirits were not much improved when we came out of the Simplon tunnel into Italy in cloud and rain, but by the time we arrived at Milan the sun was shining again, and we negotiated the marble staircases of the magnificent new station successfully in our boots. From Milan, we took the Venice train as far as Brescia, where we stayed the night.

The Adamello and Brenta mountains lie south of the Ortlcr group and roughly north-east of Lago dTseo and north-west of Lago di Garda. We proposed to cross the Adamello group from Edolo on the west (in the valley to the north of Iseo) to Pinzolo on the east. Pinzolo is but a short distance lower down the valley than Madonna di Campiglio, the best base for the Brenta. Given good weather, our only doubts were about the huts, several of which were reported to be locked, with the keys kept on the wrong side of the mountain.

We left Brescia early on Sunday by an excursion train for Edolo. Being the Italian August bank holiday the train was pleasantly filled, but fortunately unprovided with glass in the windows so that we got ventilation if not quiet; we were not the only folk cheered up by a real summer day. Arriving at Edolo about midday, we bought any amount of provisions and after lunch set out for our first hut, Capanna Baitone.

So far Binnie’s Italian had done good service, the only failure on the shopping list being butter, and that because the shop was shut. But when we asked the way to the valley up which the hut track went, the only replies were blank stares. Edolo was just off the side of our large scale maps, but eventually we found the valley and began a long steady trudge in the heat. Fortunately, the Val di Malga is a shady valley, but since the height of Edolo is only about 2,100 feet, and Binnie had already been out for a fortnight, I soon lost so much by evaporation that 1 had a permanent thirst for the rest of the fortnight.

Opinions differed about the Capanna Baitone. A letter from the Compagna Italiana Turismo told us that it was locked and that the keys were kept in Brescia. On the other hand, Binnie thought that Canon Newton had found it open, yet the C.I.T. letter said all the huts were locked. So we climbed on for about four hours and then saw a new dam which was being built across Lago Baitone, a lake a little way below the hut. Below the dam were some workmen’s huts, and as we passed a man shouted to us from one of them. Not knowing enough Italian to understand him, we went on and were discussing the best route past the lake to the hut now in sight, when he followed us and began a long speech. We tried French and then German, and learnt that the hut was locked. When we said we were English, he brought along a friend who had been in the States and in a very short time we had been offered beds in one of their huts and were being offered all kinds of food and drink. We accepted the latter and ate our supper surrounded by an enquiring audience of Italian navvies to whom the sudden appearance of two Englishmen seemed to be an event of considerable note. We found out that they worked for 16 lire a day, and had been up there for four years, working only from May to October. Some of them stayed up all winter and apparently passed the time ski-ing.

Our hosts tried to persuade us to join them with another bottle of Chianti after supper, but as we wanted to get off in good time we declined with thanks, even though promised a ride back from the canteen in a ropeway bucket.

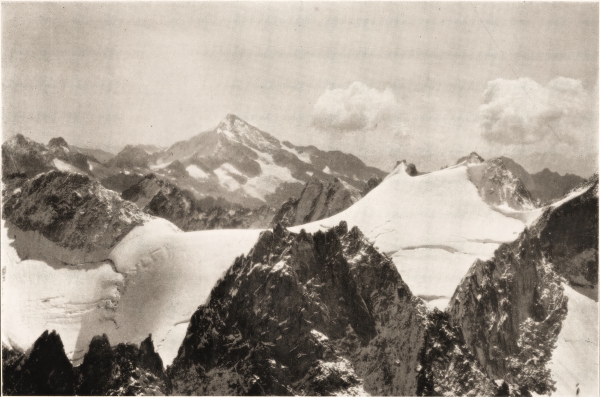

The group of mountains to which the Adamello gives the name is bounded on the north by the Tonale Pass, and east and west by the valleys in which lie respectively Pinzolo and Edolo. To the south they fade away into the lower mountains between Garda and Iseo. A deep and beautiful valley, the Val di Genova, runs west from Pinzolo right into the heart of the massif. To the north of the Val di Genova is Cima Presanella, 11,694 ft., the highest point of the group, and flanking it east and west, M. Gabbiolo and Cima di Vermiglia. The southern half consists principally of three parallel ridges running north and south, with extensive snow fields between them. The western ridge culminates in M. Adamello and the eastern in M. Care Alto, while the central ridge has no summit worthy of notice. South-west of Adamello are some lesser summits, one of which, Corno Baitone, was our first objective.

Leaving our good friends the dam builders at half-past five next day we soon passed the Capanna. It was a very solid hut and there is no doubt that had we arrived there the night before we should not have slept inside it. It was a lovely morning, though even by eight o’clock mists were boiling up from the south. By 8.30 we arrived at a little col, the Bochetta di Laghi Gelati, and after a short halt set off up the ridge for Baitone. We soon found it easier to traverse left rather than to stick to the crest and presently climbed up some easy slabs to the top (10,929 ft.) at about 10.15 a.m. Except for an occasional wisp of cloud, the weather was perfect. Though not very high, even for this country of little mountains, Baitone is a good viewpoint. Away to the north and west were the Ortler, Bernina and Disgrazia, and then over the low Aprica Pass one could look right down the Val Tellina. Behind us lay Adamello and Care Alto, the line western precipices of the former looking very formidable with their sprinkling of recent snow. Far below us, picked out against a bank of cloud in the valley, was an aeroplane Hying over the Tonale Pass. For about an hour we lay on the top, and then the call of food sent us back to our sacks at the col. From there we could see our next hut, the Rifugio Garibaldi, close to the glaciers of Adamello. We chose a route to it which gave the least unnecessary descent, but it led us across a wilderness of large and scarcely stable scree. By the end of the day we loathed the sight of a boulder.

From the Bochetta the hut was too far off to make out signs of life, and although our hosts of the dam had said that we should find a guardian there, the C.I.T. letter had said it was locked, the key being miles away. So we were considerably cheered by positive evidence that the track was used by mules, and at four o’clock came in sight of a palatial edifice with ladies and gentlemen sitting outside it in armchairs. So far from being a locked hut, one can stay at the Rifugio Garibaldi ” en pension.” Scattered round about are some ruins of war huts, and near the hut is a memorial chapel. That night we had our first experience of dessert in those parts—pears, peaches, and bunches of grapes which took nearly an hour to finish.

Next day we climbed the Adamello, taking the easy way over the col in the ridge to the north and up easy snow slopes on the east side. The north-west face, seen in profile from the hut, must give some splendid climbing. A fine morning failed to last and we arrived at the top in 3½! hours at eight o’clock

in mist and a little snow. By eleven, thanks to the cold night and the absence of sun, we were at the Rifugio alle Caduti dell’ Adamcllo, close to the Lobbia Alta Pass over the central ridge. This hut is a war memorial to the Italians killed in the Adamello district, and is at a height of over 3,000 m., and a splendid centre for .ski-ing excursions all the year round. It is open throughout the summer, and considering its height the tariff is very cheap. Its only drawback is the proximity of some heaps of war refuse. While we were there the wind was in the right direction, but had it been east………..

As we started next morning the clouds dispersed, and picking our way through the wire entanglements on the Lobbia Alta col, we crossed the glacier to the Passo di Cavento. Here we crossed the eastern of the three ridges some way north of Care Alto, and traversing south along the far side arrived at the bottom of our peak. We chose the right hand ridge of rock in preference to the steep snow of the face. This was probably a mistake, but we scrambled up over awkward blocks and then some amusing slabs to the top. Care Alto is at the south-east corner of the group, and the day being clear as well as hot, we enjoyed a magnificent view. The tops of the Apennines were just showing over the mist in the plains, while the whole panorama of the Alps from Monte Rosa to the Ortler stretched from west to north. In the east the towers of the Dolomites were silhouetted against the horizon, and much nearer the rocks of Brenta and Tosa ridge threw a deep shadow over the valley in contrast to the glistening white where the sun lit up the small patches of snow at their summits. An hour passed all too quickly, but at ten o’clock, with thoughts of the hot sun and the glacier, we started down for Malga Lares, the Val di Genova and Pinzolo. At the chalets of Malga Lares, we disposed of our superfluous bread, which had become so hard that neither coffee nor hot soup would soften it. In the absence of butter, it had not been the most popular part of our diet. We handed it to an unsuspecting cowherd, and got away before he had stopped saying thanks.

From the alp the path dropped steeply down in welcome shade to the bed of the Val di Genova. Just on our left the torrent from the Lares glacier plunged over the edge in a magnificent waterfall; unfortunately the position of the sun made it impossible to get a photograph.

The Val di Genova is a beautiful valley ; in spite of the heat and the sun on one’s back and the hard road, it has a charm of an elusive nature that makes one want to go there again. For hours, it seemed, we trudged down its stony track, which, wherever the road went downhill, consisted of egg-shaped stones set on end. As a reward, the afternoon sun lit up the end of the Brenta ridge ahead with a rosy glow, and just before the Val di Genova opens into the main valley the church of St. Stephen’s stands on a little tree-clad mound which seems to have been put there specially for the I’in pose. Another two miles along the level and we arrived at Pinzolo at half-past six.

Next day, with a key in our pockets, we started out after lunch for the PresaneUa hut, thankful that the sacks were lighter than when we left Edolo. As we arrived at the hut, it started to rain, but thanks to a tip from the Editor about turning Italian keys twice, we were soon inside, and thereafter only came out again when it was necessary to avoid suffocation from the smoke. All night it blew and rained and thundered, but when Binnie looked out at half-past three the sky was clearing. We got away at 4.4 a.m. under a clear sky with a north wind in our faces. On the glacier the wind was blowing the snow at us, but we pushed on and reached the Presanella at 9.15 after one halt. We did not stop to admire the view but hurried down a few hundred feet to a sheltered spot where we had left our sacks. After taking a few photographs and eating some chocolate we started down again, only to find that the snow which had given us foothold on the way up had been blown away, and for some way down we had to cut steps. Back at the hut we changed into shorts and made our way slowly down. We lay down in the shade for an hour to let the sun get down a little before we walked back down the Val di Genova, contrasting the afternoon’s heat with the bitter cold of 9 a.m.

Next day we took the bus to Madonna di Campiglio, and spent the afternoon in idleness watching the briskly fought final of the local tennis tournament. In the evening we met Dr. Finzi, the first Englishman we had seen, with his guide Franz Biener, and found that he too was bound for the Ttickett hut next day. Our plans were to go up to the hut, do Cima Brenta, and go round to the Tosa hut. Thence we wished to climb Cima Tosa and the Torre di Brenta and, if time permitted, to go down to Molveno and to spend a day on Garda on our way home. Finzi persuaded us to make an early start next morning and also to buy either kletterschuhe or rubbers. Binnie didn’t have much difficulty, but I got the only pair of size 45 tennis shoes in Campiglio.

Sunday morning was dull and before we got to the hut the rain began. We gave up our hopes of a climb and spent the day there. About six in the evening it cleared up and we had some wonderful views across the valley where the peak of Presanella appeared through the sun-lit clouds.

The Tuckett hut lies just at the western end of the Bocca di Tuckett, one of the two great clefts in the Brenta ridge. Immediately to the south of the pass is the Cima Brenta itself, 10,352 ft. A small glacier coming down from the Brenta fills the bed of the gorge, which is confined by imposing dolomite cliffs. Near the hut the Castelletto Inferiore provides a variety of rock climbs from the moderate to the severe.

At 5.30 next day we set out up the glacier to the top of the pass, where we dumped some superfluous luggage. Cutting steps at first, later we took to the rocks and traversed round by the ordinary route to the east side of the mountain. Steady progress up rocks of no great difficulty took us to the top at half-past nine. Clouds had followed us up the eastern side and though we waited for an hour and a half we failed to get a glimpse down to Molveno. The west was occasionally clear, but as the weather was looking worse we went down and reached our spare clothing just as the rain started.

Crossing the Bocca di Tuckett, we took the high level track or Sega Alta along the east side of the ridge to the other pass, the Bocca di Brenta, where lies the Tosa hut. Unfortunately the first part was in thick mist, but towards the finish the weather cleared a little and allowed us glimpses at close range of the towers and peaks of the ridge south of Cima Brenta, including the Guglia di Brenta, ” sharpest needle of the Alps,” as the Hochtourist calls it. The round of the Brenta from Campiglio, by the Bocca di Tuckett, Sega Alta I rack, and Bocca di Brenta is deservedly popular and involves nothing that cannot be negotiated without a rope or axe.

The improvement in the weather was only temporary, and before we got to the Tosa hut it was raining steadily again. Finzi and Franz arrived soon after us, having done one of the “super” climbs on the Castelletto Inferiore, and come round the west side of the ridge over the Bocca di Brenta. We meant to start for Cima Tosa next morning, and Finzi was anxious to try the Guglia, but the rain went on all night without a break. Finzi then suggested to us that we should join up with him and move off for a day or two to the Engadine or the Bregaglia. After a lot of hard work vvilli time-tables we decided on the Bregaglia, as from the Engadine I should not have been able to get back to England in lime unless everything in the programme went off without a hitch. So we went back to Madonna di Campiglio, loaded ourselves into Finzi’s roomy car and he drove us via the Tonale Pass and the Aptica Pass to Sondrio in the Val Tellina.

Next morning we drove up the Val Masino to Masino Bagni where we garaged the car and after a terrific lunch went up to the Rifugio Gianetta. The bad weather seemed to have disappeared for good, but as soon as we saw Piz Badile it was obvious that our proposed route, the West ridge, would have too much fresh snow on it to be feasible. Finzi, who had of course been there before, suggested trying the east ridge of Piz Cengalo, which he had not done. Next morning was fine and cold, and we were soon round the end of the south ridge of Cengalo, and going up the glacier to an obvious col between our peak and what was probably the Gemelli. The Badile hut has four maps on its walls, all different, but we came to the conclusion that one of them was more or less correct. Unfortunately it bore no trace of origin.

Breakfasting in the sun just above the col, we were soon off again, over rocks covered with an inch or so of fresh snow, but at 9.15 Franz peered over the top of something and announced that we were “abgeschlossen.” A fair sized gap separated us from the true east ridge of Cengalo, which rose on the far side in steep slabs thickly plastered with snow. The descent to the gap would have gone all right, but the slabs on the other side were out of the question in that condition. A traverse across to the south ridge was barred by a little couloir with a nasty pile of debris at its foot into which the sun was now shining fully. We thought about going right to the bottom and round, but the day seemed to be one made for laziness rather than hard work. So we lay in the sun for a couple of hours, watching the cotton-wool like clouds in the Engadine and the Rhine valley slowly melting away, and trying to identify all the mountain groups from the Dom to the Disgrazia and to find the little col above Maloja which is said to be the watershed between the North Sea, Black Sea, and the Mediterranean.

That, as far as I was concerned, was our last climb. Dr. Finzi very kindly drove us down to Colico next day, where after a bathe in the lake, he said good-bye and went up to join a friend at Maloja. Binnie and I made our way back via Milan and parted at Brigue, where Binnie tried to get revenge for an earlier defeat on the Bietschhorn. But as usual this year, the weather broke again and he was disappointed.

The Adamello and Brenta mountains are not very high, nor very difficult, but they form a delightful district for a short holiday. We found the huts both well kept and cheap, those in the Brenta group being semi-hotels which are apt to be rather crowded. We were far better treated by the weather than were people in Switzerland, where strong men abandoned climbing in disgust for a life of ease by the Italian lakes. True, it stopped us doing the Tosa and the same storm produced the snow which foiled us on Cengalo, but had we stayed another day at the Tosa hut no doubt we should have got our peak, and had any of us known the east ridge of Cengalo, we should not have considered it under the conditions. So we were thankful to be amongst little mountains, relatively quite lofty, as the valleys are so low ; and moreover enjoyed t he exploration of a district seldom visited by English climbers.