A Fortnight In The Lepontine Alps

By W. E. Evans.

” Parlez-vous anglais? Good.”

” Parlez-vous anglais ? Blast.”

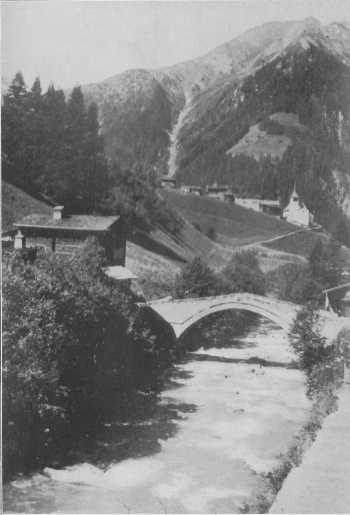

With these two opening gambits, Crowe and I made our way in June, 1934, across France and half of Switzerland to the village of Binn. As the location of Binn baffled the omniscient Mr. Thos. Cook, it may not be out of place to define it. South of the Rhone valley, Binn is nearly centrally situated on the north side of the chain of the Lepontine Alps, the ridge of which here forms the Italian frontier, and is about half-way from Brigue to the Rhone Glacier.

Very good, but why go there ? The main stream of mountaineers, flowing contrary to the laws of gravity up the Rhone valley, is dammed and diverted at Sion and Visp ; a part, bound for the Dolomites perchance, continues a few miles, and then dives through the Simplon ; the few survivors who go further, rocking and lurching up the quaint little Furka Railway, must surely aspire via the Eggishorn to the heights of the Oberland, for nobody, it seems, turns south beyond Brigue—nobody, that is, with nails in his boots. This, at least, was the opinion of a professor in the classics, who had come, in his old age, to enjoy a restful holiday at Binn, but who spoke with the authority that only a score of seasons in the Alps could give.

Eager to drink from this fountain of wisdom, we innocently confessed, one evening after dinner, that this was our first visit to Switzerland.

” Whatever made you choose Binn ? “

We blushed, and tried to explain. We admitted that we had found the rock very rotten.

” What would you expect with this geological formation ? “

Undaunted yet, we countered by claiming that we were at least getting good experience of snow-climbing.

” No more than you would in Wasdale in the winter, I imagine.”

After that we discussed the Test Match.

Let me say immediately that we had no regrets at having chosen Binn, and, with the greatest deference, I hold the learned professor’s scorn to be misplaced. For a party of two, with some mountaineering and rock-climbing experience in the British Isles only, but no knowledge of snow or ice, the choice of a suitable district is difficult. Guides were a luxury we could ill afford. A friend who knew this district told us that here we should find variety of climbing, nothing beyond our powers, no glaciers, and no need of guides. We took his advice, and are grateful. The only hotel has an English-speaking proprietor, who knows the needs of climbers ; it is clean, comfortable, and inexpensive despite the adverse exchange.

In writing of the days we spent in and around the Binntal, I am conscious that those who have climbed in the Alps will find them unremarkable, yet to us the pleasures were unique. We had all the joys of discovery and endeavour in a new field. The first sight of high hills ; to carry an ice-axe, not because ” there may be some snow in the gullies,” but as an essential piece of equipment; even to start out before dawn ; all these are adventures at first. If I write at all, I must record them.

The approach to the Alps has been too often described. A sleepless night in a stuffy French train does not aid the appreciation ; but we were not disappointed, only strangely excited, by what we saw as we travelled up the Rhone. Later, the ten mile walk from the nearest railway at Fiesch to Binn seemed a never-ending purgatory. It was exceedingly hot, the road was dusty, our clothes and shoes were all wrong, and our rucksacks too heavy. Of course, it was uphill all the way. The thought of climbing mountains was singularly distasteful.

Yet, as we approached the hotel at Binn in the staring midday sun, sweating, tired, foot-sore, and wanting above all to sleep, even then we knew that the Ofenhorn must “go.” It should wait only until we had made our preliminary canters, ” found a length,” as it were.

The walk to the Eggerhorn, a good view-point overlooking the Rhdne, was typical of the district. The path first winds upwards through fragrant pine-woods, where, almost at every turn, a snow-capped peak, sometimes a new one, sometimes the same in a different aspect, shows itself ever lovely, through a break in the trees. Then it crosses the upper pastures, a many coloured carpet of June flowers, to the ceaseless yet never wearisome sounding of cow-bells. Higher still, where the soil is thinner and poorer, are the gentians, surely the bluest things on earth ! The purity of that deep colour, that scorns to flirt with either green or purple, fascinates the eyes.

Coming back that first day, I remember how, with great caution, we avoided crossing some hard snow, many feet thick, which bridged a little watercourse. We knew, a week later, that it would have borne an army !

The Wannenhorn, about 9,400 ft. high, gave us a taste of both rock and snow, but presented no problems. I had, however, the utmost difficulty in dragging my leaden boots up the last five hundred feet, and felt extraordinarily weak and shaky at the top, where it took a long rest and much lunch to return to normal. The obvious explanation is altitude, but why did we feel nothing of it the day before, at nearly 9,000 ft. ? Later, up to our highest point of about 10,500 ft., we experienced nothing which could be definitely attributed to altitude.

We descended by an easy, but excessively rotten rock ridge, and a long snow slope, fairly hard, and steep at the top. With Crowe anchored safely on the rock, I cautiously kicked steps down to the limit of the rope, drove in the axe, belayed, and watched Crowe proceed with equal caution until he was the rope’s length below. We continued thus for, perhaps, 500 ft., and half an hour, while the bottom of the slope seemed no nearer, before I lost patience. I had slipped once, and stopped myself comfortably with the axe. So we tried a glissade, and ten minutes later we were down in the Fleschen glen again, having had the time of our lives ! This, however, was the only good glissade we had during the fortnight, because we were usually descending western slopes, softened by the afternoon sun, but it was the start of our confidence in snow. At first we always went for rocks in preference, to the great astonishment of our ex-guide landlord. We found later that snow was faster both up and down.

The Ofenhorn does not dominate the Binntal. It is too far off for that. But its’ splendid form, isolated, and framed between the slopes of the valley, is a constant exhortation, whether seen at dawn, at noon, or by moonlight. It was under a full moon that we set out at 3 o’clock. Three hours steady going up the gently rising valley took us to the final slopes of the Albrun Pass, a pony-track into Italy. Turning east here, in less than an hour we were on the snow-slopes, which we took to calling glaciers on the authority of the map. I think the only glaciers we ever saw were those in the Oberland, from the opposite side of the Rhone valley, but it is a convenient word, and sounds well!

Already the loveliness of the day and what it disclosed had surpassed anything we knew. We had seen the day breaking behind the Ofenhorn, and printing its form on our minds as it did on the sky ; westwards, everything was rose-tinted, the little clouds against a turquoise sky, the tops of the mountains, and then their lower slopes, as the shadows of the higher peaks in the east drew in before the rising sun. When those shadows overtook us, we made our first stop. There were other mornings when we reached the snow, the sunshine, and breakfast-time together ; it is a happy concurrence.

There followed an hour of step-kicking up a broad couloir in sunshine which enhanced the contrast between dazzling snow and the high black walls of rock which make the Eggerofen an impressive approach to the peak. Then a rock scramble up a ridge with one pitch whose exposure, rather than its difficulty, called for the rope. The west peak, to which it led us, is separated from the higher east peak by a little col; the distance is, perhaps, 200 yards ; the time, five minutes by the guide-book. Alas, the ridge was wickedly corniced, and a flank attack was indicated. A tricky descent of some loose rock was followed by a 300 ft.

traverse of a steep slope of soft wet snow, in which we floundered nearly to our waists. It was good to escape from the morass, and scamper up the final rocks to our first 10,000 ft. peak. The book’s five minutes had taken us fifty. Was that snow dangerous ? Neither of us knew ; both thought it was ; by tacit agreement, the subject was not raised until we had safely recrossed it, with the peak in our pocket!

Meanwhile, the sky had darkened, a soft snow had begun to fall, and more black clouds were riding up from the south. There had been distant rumbling, too, from Italy. We had not descended far before the storm was with us, with all the proper stage effects—thunder like whip-cracks about our ears, lightning of incredible brilliance heightened by reflection from the snow ; ” Phsst ” said my ice-axe to every flash, while Crowe reports that the brim of his hat hummed a merry tune. I cannot understand why the experience was not more alarming ; true, it was not a violent storm, and we hastened to leave the ridge on which we were when it broke. Yet there must have been elements of danger in it, and perhaps we should have been wise to dump our axes until it had passed. I was too much interested in the phenomena to be frightened, and I remember only being delighted that I was so lucky as to be present at such a performance, instead of having to be content with the comparative inadequacy of written accounts—even Whymper’s.

We had other good days after this, but there was something unique about the hours spent on the Ofenhorn which we never quite recaptured. There were pleasant off-days, basking in the sun, and lazily watching the countless butterflies, as lovely and varied in their colours as the June flowers amongst which they were so busy. There were strolls through the pine woods, and attempts to solve the annoying problem of how to photograph dark foreground and distant snow with any recognisable result. There was even an occasion when I was moved to write what I thought were verses on an Alpine valley, a clear indication that it was time the valley was forsaken for the hills again.

The ascent of the Bettlihorn is to be recommended for the magnificent views it gives. From the summit, every peak of the Lepontine chain, from the Blindenhorn to the great bulk of Monte Leone, its bowels pierced by the Simplon Tunnel, can be identified, the whole a castellated rampart above the plains of Lombardy. The Lepontine Alps resemble the Coolin in this, that their passes are comparable in height with their peaks, the highest and lowest points in the ridge being 11,670 ft. (Monte Leone) and 7,900 ft. (the Albrun Pass). Northwards from the Bettlihorn, the dark trough of the Rh6ne valley, with its silver thread of river, is seen, and beyond, the giants of the Oberland, the high ground so foreshortened in the clear air, that the peaks seem to jostle one another amidst a maze of twisting glaciers.

Almost our last expedition was to the Helsenhorn, a fine snow peak on the frontier, and the highest within our cruising range from Binn. The landlord, on hearing of our objective, sighed. Our predilection for rocks, which was past his comprehension, had led us earlier to ignore his advice, and he was not unnaturally a little peeved.

” Ach, you vill lose der vay again,” he said.

But not only did we find the way and keep to it, but kept the guide-book time to the summit to boot, so that this excursion had a certain neatness of execution which pleased us. There were, however, aesthetic pleasures which far outweighed these childish things ; it is a delightful climb. A steep ascent at the head of the leafy Langtal, beside a fine cascade, leads to a great amphitheatre, the floor mossy, flat, with a peaceful stream meandering across it, the walls a full 3,000 feet of rock, broken only by the entrance whence we came. On the right are the cliffs of the Hullehorn, ahead is the Ritter Pass, safe from a frontal attack, on the left the rock buttresses of the Helsenhorn. The only access to the rim of this great cup in the mountains is in its south-east corner, where the route to the Ritter pass finds the walls broken, and less steep. This we followed to the snowline, where we stopped for rest and food.

The sun was rising over the Helsenhorn behind us, as we watched the shadow sweep across and down the flank of the Hullehorn a kilometre away. The artillery opened fire. As each snow-filled gully came under the sun’s rays, its imprisoned rocks began to tumble, until, in a quarter of an hour, there were four or five batteries engaged. The noise, like thunder, echoed and amplified by the encircling hills, seemed out of all proportion to its cause ; at the distance, the falling stones could hardly be seen, and their downward progress seemed gentle and leisurely. It was a fascinating entertainment, and especially interesting by comparison with the little avalanches of new snow which we had seen falling from the Schwarzhorn a few days before. Again at a distance, it was incredible that the slowly falling wave, its soft whiteness seeming imponderable, should be the cause of the muffled thunder that filled the Fleschen Glen. These incidents, more than anything else, impressed on us the greater scale of these than our British hills.

A steady climb on rock and as yet unsoftened snow brought us uneventfully to the top. Two curious things we had seen. An apparently cheerful spider at 10,000 ft. in the middle of (to him) a vast expanse of barren snow, and innumerable small leaves on the melting surface, having been blown perhaps 5,000 ft. to this height by some great wind, which we were content to contemplate without asking further demonstration of its powers.

It was a day of un-English clarity of atmosphere; there seemed to be an end of visibility only where sheer distance annihilated form. The fleckless sky deepened from an azure horizon to cobalt at the zenith. To the west, the mountain masses beyond Monte Leone, containing all the giants of the Pennine Alps, too distant to identify, made of the skyline a jagged frieze. Looking north, the Oberland was a wonderful sight. The sunlight burnished the rock to a glowing purple-brown, above which the glistening peaks stabbed the sky— Finsteraarhorn, Aletschhorn, Griinhorn, the Eiger group— so many that were only names until that hour, when, in the perfect silence sometimes attained on mountain tops, and very seldom elsewhere, we found also ” a great easing of the heart.”

******

Lausanne : a calm summer’s evening beside the lake, a dinner chosen with care and perfectly cooked, a suave and satisfying wine, all partaken in the most charming company, brought this successful fortnight to an elegant close.