Mountains Of Yorkshire

By J. K. Crawford.

I. The Howgill Fells.

The Pennine Chain, known to British schoolboys as the backbone of England, extends from the Cheviots to the Peak. It consists of three blocks of mountainous country divided by two gaps or passes.

The northern Pennine area lies between the heads of the Tees, Wear and South Tyne on the one hand and the fertile valley of the Eden on the other and includes Cross Fell in Cumberland, also Mickle Fell in Yorkshire. Between it and the next section, the wide and high pass of Stainmore comes sweeping over from Teesdale to Edendale, from Bowes to Brough. An ancient and elevated highway this, used by prehistoric man, brigand, and Roman, and by a modern motor way (except in the snow blizzards of winter) from England to Scotland.

The middle Pennine area falls almost entirely in Yorkshire and ” is chiselled into high relief with the mountains and dales of the North-West Yorkshire Highlands ” (Kendall and Wroot). South of this in the Skipton district lies the Aire Gap, the lowest and most accessible of all the passes through the Pennines.

The southern Pennine area is the great wrinkle which ends in the Peak district of Derbyshire and on the slopes of which have grown up the industrial towns of Yorkshire and Lancashire.

It is, however, the middle block which is of such interest to the Yorkshire Rambler. Here lie all the two thousand foot tops (about forty) of Yorkshire with the exception of Mickle Fell and its satellites.

The Howgill group, situated partly in the north-west corner of the West Riding of Yorkshire and partly in Westmoreland, are more akin to the latter owing to their geological formation. They are slate hills separated off from the limestone and gritstone of Yorkshire by the line of the Dent Fault, so that approaching them, say from Baugh Fell, there is an abrupt change from the long moorland ridges, coarse grass and peat bog to smooth steep green slopes. Their steepness indeed and rounded summits give them a distinction and an outline which makes up for lack of great height, as they only range from 1,500 to 2,200 feet. The river Lune, with its head waters, almost surrounds the Howgill Fells, the Rawthey completing the circle, and the West Riding boundary crosses them from Rawthey Bridge to Carlin Gill, a little north of Low Gill Junction. Sedbergh, famous for its Public School, is the natural centre for this region and there are delightful approaches on every side, particularly from Kendal or Kirkby Stephen.

It may be asked, what are the attractions of these hills, which nobody seems to write about and which appear so bare (Wordsworth’s ” naked heights “). In answer, I would say, firstly, that to a Yorkshireman, they are so unlike his familiar scenery, and secondly that, owing to their comparative remoteness from large centres of population, they afford to the hill-lover a sanctuary of quiet and repose. During my tramps over them I have rarely seen anyone else, and I include a Bank Holiday, which is now hopeless in the Lake District. It is grand walking country with wide expanses of hill and sky. Beneath lie the deep little glens, interlacing and with little room except for the becks which occupy them.

My first introduction to the Howgill Fells was due to the Editor of this Journal who accompanied me in traversing them from Crosby Garrett to Sedbergh on a late autumn day. After a wild and stormy night, the rain had ceased and we found it a breezy walk from Ravenstonedale over Spengill Head and steeply up and down Yarlside to the Calf. In fast gathering darkness, we had a little difficulty in descending but eventually picked up the track leading south over Arant Haw and Winder.

Some years afterwards, I again crossed, this time from west to east. E.H.J, and I had been on a walking tour in the Lakes one blazing hot Easter, and finishing up at Kendal, decided to delay our arrival home as long as possible. Alighting at Low Gill Station, we found a rickety foot bridge over the Lune, where Fair Mile Beck enters it. The weather had completely changed from summer heat to grey skies and chill winds, as we pursued the beck upwards. On the top of

Fell Head it was blowing hard with thick mist and we had to use the compass carefully in getting round the head of Long Rigg Beck and on to the Calf plateau, from which we descended past Cautley Crag.

One lovely morning in June, I left Sedbergh by Joss Lane and ascended Settle Beck Gill between Crook and Winder. In half an hour I was in the heart of the hills, a lark singing joyously overhead and a cool north-west wind blowing. Eastward, Wild Boar, Swarth, and Baugh Fells appeared in bulky outlines and a delightful track leads round a corner, where a surprise view greets the eye of the western ridges and combes of the Howgill Fells. I was alone and this gave me ample opportunity to stop at any moment, study the map, take a photograph, and generally please myself, a very pleasant relaxation occasionally.

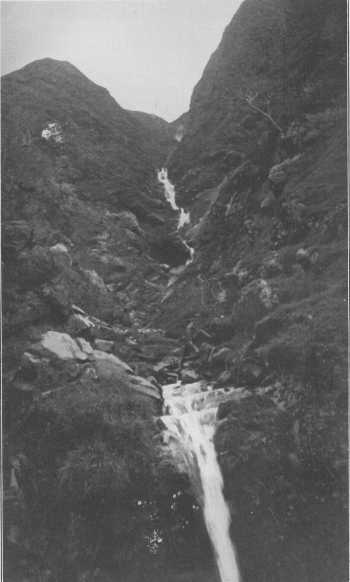

Continuing down to a saddle (on the one-inch map, O.S. Popular Edition, sheet 20, close to the t of Brant Fell) with a wire fence on the right overlooking Hobdale Beck, the path mounts steeply up Calders. Where it turns to the right towards Great Dummacks, I left it and crossed Bram Rigg Top. These hills are very confusing in mist, as a previous experience shewed. The Calf (2,220 feet), the highest summit, is seen as a long ridge beyond the depression which forms the source of Cautley Beck. I soon reached the cairn, which lies at the western edge and consists of only a few stones, commanding a glorious prospect of the Westmoreland Hills. Keeping to the ridge and county boundary over Bush Howe, I dropped to the narrow depression at the head of Long Rigg Beck. From here I had planned to make for Simon’s Seat and finish up at Gaisgill, a station away to the north, but instead ascended Wind Scarth and Fell Head, overlooking the beautiful valley of the Lune. My intention was to find Black Force, which lies about a mile to the north. So descending a gill, which is not named, I arrived at the top of a gloomy ravine, where the stream falls sharply into Carlin Gill. The best view is obtained by scrambling down to the foot and viewing the Force from below. I was now practically at the extreme north-west corner of Yorkshire (over 100 miles from Spurn Head) and in a lonely and romantic spot.

It seemed a suitable place to lunch, despite sinister stories of suicides near by !

A horribly steep climb led back to a track which winds round the western side of Fell Head and descends gently to green pastures. After a while, I stopped and dozed in a sheltered spot, being only awakened by the whistle of a train rattling down from Shap and Tebay. Proceeding down a wooded ravine against which the dark fells made a fine background, I came upon the pleasant hamlet of Howgill and paid a visit to the tiny church. The old man who unlocked the door (he did not look very old) told me he was eighty-three and shewed me a photo in the vestry of his grandfather, who had been the parson there for sixty-four years. The church used to occupy the spot where the grocer’s shop now stands, close to the pretty bridge. He spoke also of long severe winters unknown to the modern generation and deplored the lack of contrast to-day. When I complimented him on his wonderful fitness, he put it down to a hard upbringing and simple diet. Saying good-bye, I wandered slowly back along a lane full of wild flowers to Sedbergh in the evening sunshine.

The previous day having been spent wholly on the Yorkshire side of the Howgills, I determined to see something of the Westmoreland portion. An early train took me, a solitary passenger, from Sedbergh to Tebay. From the latter station I walked back along the high road for half a mile or so, and at Lune Bridge struck up on to Tebay Fell. There was a beautiful light over the hills towards Eastern Lakeland contrasting with the darkness of the gorge just below me. Turning eastwards over Archer Moss, where the going is heavy, I kept as high as possible but had to descend to the head of Uldale and mount again to Docker Knott, where another little valley lay between me and Simon’s Seat. This was quickly overcome and soon I stood on the grassy summit, viewed from which the perky little tops seemed to pop up in all directions.

Langdale lies far below and by its cheerful stream I ate my sandwiches in complete isolation, except for the sheep, with which this country is well populated. There are no walls to climb here, unlike most of our West Riding hills.

Mists and fine rain now came drifting over from the west as I followed a beck up to the central ridge at Hare Shaw. After crossing two feeders of Cautley Spout and slipping into one, I descended a scree shoot rapidly to the great hollow below. At all times it is an impressive scene, a magnificent fall of water with the dark Cautley Crags on the left and the steep slopes of Yarlside on the right. Indeed the mists flying over the Cautley ridge above the corrie gave a faint suggestion of Arran or Skye. Leisurely keeping company with the beck to its junction with the Rawthey I walked the remaining five miles by footpath and cart track to Sedbergh, for tea and the evening train to Leeds.

II. Baugh Fell.

The traveller on the Midland route to Scotland, approaching Hawes Junction at an elevation of over 1,200 feet, looks down on his left to the charming valleys of Dent and Garsdale. Flanking the north side of the latter, lies the enormous bulk of Baugh Fell, one of the wettest of mountains and the home of innumerable torrents which tear the bleak hillside. It is not a very interesting climb from any side to its summit, which is seen to be about two miles in length, extending in the form of a crescent and consisting of two flat tops. East Fell has four tarns, situated at the head of Rawthey Gill, across which ravine, a good mile away, lies the cairn of the West Fell, with its solitary sheet of water. Nor is it, one would think, a conspicuous mountain, but oddly enough till very recently it appeared on every map of the North under the form Bow Fell, even on those which ignored Cross Fell.

Many Yorkshire hills are conveniently included in a cross country walk and on one occasion the writer left Sedbergh en route for Hawes Junction (or Garsdale as the station is now called) by way of Baugh Fell. The year was barely a month old, as I stepped briskly out beneath a cloudless sky and in brilliant sunshine, though the wind was cold and snow lay on the tops. After crossing a bridge about a mile out of Sedbergh on the Cautley road and turning down a narrow lane to the farm house of Fellgate, I set off across the long moor towards West Baugh Fell, passing I suppose near the entrance to Dove Cote Gill Cave, of the existence of which I was not then aware. The way is trackless and boggy and I was soon very warm, glad to sip the mountain stream before breasting the final slope. Seated by the cairn, sheltered from the north wind, the view was magnificent.

Above the dark ravine of Cautley, the Howgill Fells appeared to great advantage, their covering of snow making them appear much higher. The valleys converging on Sedbergh were well seen and the eye travelled from Dent Crag and Whernside to the heights beyond Wensleydale and the Mallerstang group, with Wild Boar Fell prominent. The West Tarn lies close at hand and after visiting its shores I tramped along the broad tableland to the point marked 2,216, rounding the head of Rawthey Gill and encountering deep snow drifts on the East Fell. Steering straight for a plantation across the dale under Rise Hill, I descended steeply and somewhat laboriously to the tiny church of Garsdale. I had now five miles of road walking in front of me (a proceeding I usually abhor), but on this occasion it appeared as nothing, for in this green and sheltered vale, beside the river Clough, which appeared first on one side and then on the other, spring seemed to have arrived. I passed the entrance to Grisedale, ancient home of the wild boar and containing some queer place names (e.g., Mouse Sike) in the few dwellings which comprise its little community. Arrived at the Moorcock, a cup of tea was welcome, before returning to the station for the train to Ribblehead, where the jolly companionship of a Y.R.C. meet at the Hill Inn and the kindly care of Mr. and Mrs. Kilburn rounded off the day.