The Royal Grotto Of Postumia (Adelsberg)

By J. W. Puttrell.

” See Naples and die ” may be the desire of the world tourist, but the ardent cave-hunter would doubtless change the venue of his passing to Postumia, near Trieste, for there is scarcely another cave on earth so noted for its vastness, grandeur of decoration, and historic associations. Here nature shows herself as a perfect artist, and with the simplest of tools (the river Poik and silent, dripping water) has produced an amazing variety of effects of which I propose to write. The old name of the town, Adelsberg, near to which lies the cave, should be written Adlersberg, signifying ” Eagle’s Mount,” for the rocky hill capped by the ruins of a castle is supposed to have been the haunt of eagles in olden time. In the Slavonic language, also, the place is known as Postojna, which signifies an eagle, but since the territory was ceded to Italy, it has been named Postumia.

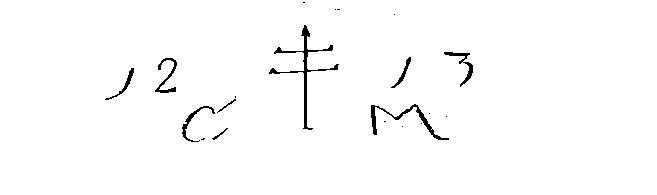

The earliest records of this magnificent cave date back 300 years, but many interesting inscriptions still legible on its walls such as :—-

clearly indicate that it was visited centuries earlier. These inscriptions, including the pious one of ” Philip Wenger, Praise to thee O God, 1518,” ceased about the year 1676, leaving a blank period of 140 years from 1676 to the year 1816 when the cave was explored by Ritter von Lowengeif. This long interval of neglect, after nearly five centuries of local visits, came about because the old passage had become so choked by falls of rock that in one place it was only thirteen inches wide. In 1830 M. Alois Schaffenrath, the district surveyor, completed the first plan and views of the grotto. These I am proud to possess. In 1854, Dr. Adolf Schmidl, one of the most famous cave explorers of the past century, published his fine monograph, ” Die Grotten & Hohlen von Adelsberg, Lueg, Planina & Laas,” under the auspices of the Austrian Government & the Imperial Academy of Sciences, Vienna. Other explorers continued the work, such as M. E. A. Martel in 1893, and in later years, cav. Luigi Vittorio Bertarelli, cav. G. Andr. Perco, etc.

When our party arrived by rail from Laibach and Rakek, two days’ journey from London, we changed several £1 English notes for 90 lire each, Italian money, then took our seats in a conveyance bound for the cave, entrance fee 35 lire, 7s. gd. It was a brilliant sunny morning when a wide stretch of pastoral land opened to our view, with a winding stream in mid-distance. To a stranger, the presence of any great marvel of nature would not be apparent, but to the nature-student the stream and the range of limestone hills to the right promised well.

Arriving at the entrance before cave-opening time, we took stock of our surroundings from the bridge below. Evidently in remote ages a great earth movement had occurred here, as the grey rocks were tilted at a steep angle out of their former level state.

The Poik (Germ. Piuka, Ital. Piuca), having found a weak joint in the tilted strata, had by persistent action formed a wonderful range of caverns since richly adorned with dripstone. It had been our pleasure to go further north a few days previously and view the Planina cave where this same river Poik issues to daylight after a subterranean journey of nearly ten miles. The hill top above the Royal Grotto commands an extensive survey not only of the Adriatic and the Julian Alps, but by way of contrast, also the featureless waste tableland of the Carso, the source of the fierce wind the bora. Below the cave, the view from the bridge over the Poik and gorge clearly illustrates how the grotto has been formed.

Whilst meditating here we observed people moving towards the entrance and quickly joined them. A splendid wrought-iron grille 20 feet high spanned the opening, and the stonework above showed the date ” 1819,” when the grotto was formally opened to the public. Passing down a corridor we stepped into a miniature train and soon the motor-driven cars were rolling along the narrow-gauge rails. Far below to the right we saw and heard the Poik rumbling through the first chamber, the lofty ” Cathedral ” striking at once the impressive note of greatness. We then entered the Ball Room, with its level floor, and mentally pictured the lively scene here on festal days, when hundreds of peasants in their national attire dance merrily in the glare of multi-coloured lights against a natural background of richly tinted formation. Guide-books hint at 8,000 and more dancers, but 800 would perhaps be nearer the number for a dance-hall of its capacity. It is 160 feet long and 100 feet broad. After passing the Crystal Cave we noticed the ” Castle Ruin ” opposite.

Soon the choice of two ways offered itself. The train took the left passage containing the ” Diamond ” pillar, then came the Belvedere, and soon afterwards the entrance to ” Tartarus,” into which dread region the ordinary tourist does not enter, nor will he desire much acquaintance with this modern place of torment for it descends to the treacherous waters of the Poik. It is pleasant to recall that in September, 1893, our Honorary Member, M. Martel (now in happ}’ retirement) did much brilliant work in this area.

Near the Belvedere, darting about in a concrete pool are seen the small blind white and pinkish lizards, the flat-headed Proteus Anguinus, one of the strangest creatures living, possessing two pairs of legs and mere dots where eyes should be. Notwithstanding their blindness they appear very sensitive to the glare of the electric light and seem happier when it is switched off and they can again enjoy the gloom. Their skins are so translucent that the hearts, which beat about 55 times in a minute, can be clearly discerned.

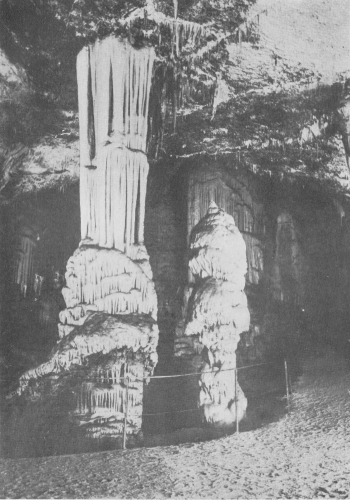

Next we proceeded to the Concert Hall, a lofty cave capable of accommodating a large audience and of staging an orchestra of 100 performers. Operas and concerts are given here during the season under the leadership of such famous composers as Mascagni, of Cavalleria Rusticana fame. Adjacent, and within the cave, is a real Government Post Office for the purchase and despatch of postcards, etc. Passing to the right from the Concert Hall on foot we observed a stalagmite column appropriately named ” The Brilliant ” a sparkling introduction to ” Paradise,” the most beautiful and elegant of all the grottos, the sanctum sanctorum so to speak. Joseph’s coat of many colours might have compared unfavourably with this gorgeously decorated temple of nature. Every inch of the parent rock is covered by dripstone, the countlessly facetted enamel scintillating with every rainbow colour like a choice piece of Japanese cloisonne. We reluctantly left this jewel house, a masterpiece of nature, and resumed our tour past the then closed entrance to the Bertarelli Gallery, where there is a bronze medallion of the famous explorer. This passage, 1,600 feet long and only recently opened to the public, connects with the Black Cave and the mysterious Poik, which flows through partly explored channels to issue eventually from the Kleinhausel cave at Planina, where it is known as the Unz. Further on the stream again disappears underground, and on its reappearance to daylight again changes its name to Laibach. Hastening on, for there is much to see in this Aladdin’s cave, we commenced the return journey through the ” Valley of Limbo” until the largest chamber was entered. This is named ” Mount Calvary.” Here underground is a hillock with an elevation of 150 feet, ascended by a sinuous path skirting stacks of rocks of varied size and shape.

Ages ago this large cavity experienced the shock of an earthquake when huge rocks were hurled from its roof and sides, creating a scene of the wildest confusion. Happily the scene is now changed, for nature in the long interval has made good by silently and artistically draping everything with glistening calcareous deposits varying in colour from rich crimson to pure white. She has indeed bestowed her favours here with a lavish hand, for the visitor winds his way to the top of the hillock through group after group of stalagmites and tier after tier of majestic cones and columns, here in Doric style, there in Gothic, or yonder Baroque of the most bizarre type. At the foot of Mount Calvary is the terminus of the miniature railway, which affords easy transit to the main entrance by the passage near the ” Sepulchre Stall.” This takes you through the grand ” English Church ” and the Column Avenue, also under the curious ” Fallen Column ” and later by the well-known ” Curtain.” I have seen longer and lustier dripstone curtains, but this transparent white specimen, over twelve feet long, ornamented with a striped border and scalloped edge, is a masterpiece of its kind. Presently we entered the sombre ” Tomb Hall,” then once more traversed the long gallery leading to the ” Cathedral ” where again we heard the roar of the now familiar Poik. All too soon we left this wonderland and emerged into the sunlight of a mundane world.

In all our underground travel we had not seen such immense and beautiful scenery, and although possessing a fair knowledge of what has been written about the Royal Grotto, we could only remark in the words of a royal queen, ” the half was not told me.”

It is not surprising to hear that 200,000 persons visit this premier palace of the nether world yearly. The grotto is brilliantly illuminated (750,000 candle power) and its eight miles of well-made paths, along with the two delightful half-hour motor runs, enable old and young alike to view its treasures with the greatest comfort.

Much is expected from the enlightened directorship of cav. G. A. Perco, and the public as well as the keen student of nature will welcome further scenic effects and the prospect of new grottoes. At Postumia we find the first and as yet the only Zoological Institute devoted to cavern animal life and flora. Three great halls near the entrance are there in use, one for the study of subterranean flora, another for that of cavern animal life such as the Proteus, a third reserved for experiments on the influence of cave atmosphere on non-cavern animal life. Thus Italy is in the forefront of all the’ nations in the scientific study of caves and cave life.

Shakespeare affirms that ” to gild refined gold or paint the lily is wasteful and ridiculous excess.” Accordingly I will not attempt to further praise the Royal Grotto of Postumia. Give it a visit and if a world tourist you will confess that, though different in character, it ranks with such renowned sights as the colossal Grand Canyon of Colorado, the exquisite Fujiyama of Japan, or the peerless snowclad Himalayas viewed from Darjeeling.