The Underground Course Of The Monastir River

By G. S. Gowing.

Easter 1935 should long be remembered in the annals of the Club, for it saw the first official Meet to be held off the island of Great Britain. In the early days of our history the more primitive and perhaps more restful means of transport available to members limited the meets to the vicinity of Leeds. Then, with the advent of the motor-car, we went further afield, to the Lakes, to Wales, and to Scotland. And now we have taken another step and held a meet across the sea in Ireland.

It is not, of course, the first time that the island has been visited by members of the Club ; in fact it was the earlier explorations of Rule, Brodrick and others (see bibliography at the end) that suggested the idea of a meet at Enniskillen. The accounts they published in the Journal and elsewhere show that they explored the ground with great thoroughness ; but still there seemed the hope that new caves might have opened out in the quarter of a century that had elapsed since their work was performed. And so, late on the eve of Good Friday, 1935, a party of nine Ramblers might have been seen boarding the Belfast mail-boat at Heysham, complete with rucksacks, rope ladders and other caving impedimenta, en route for the limestone regions of County Fermanagh. The crossing proved to be calm, a good omen, and particularly fortunate for those of us who braved the Bank Holiday crowd that thronged the confined space allotted to the steerage passengers. The party took one car with them and hired another in Belfast and so a few hours’ run along concrete roads, a stretch through peat bogs S. of Lough Neagh, and then miles of primrose bordered lanes, brought us to our hotel in Enniskillen in time for lunch. A steady drizzle continued without ceasing from landing in Belfast to the time we turned our backs on the caves on Monday, but with mild temperatures.

The border region of the counties of Fermanagh and Cavan bears a strong geological resemblance to the Craven District.

Masses of Yoredales and grits surmount large areas of carboniferous limestone, in which pot-holes and caves occur. On both sides of Upper and Lower Lough Macnean, south of Lough Erne, such hills rise to about iooo ft., while a group to the south, culminating in Cuilcagh, reaches twice this height. The caves and pot-holes of the region fall naturally into three groups, those on Cuilcagh, those on the hills north-west of Boho, and those in and around Boho..

After a careful study of the literature, we decided to tackle the first of the three groups, since here appeared most chance of breaking new ground. The previous expeditions had made their base at a little village called Black Lion, but this was out of the question for us, since it is now in the Free State, the caves being in Northern Ireland, with no recognised frontier post for motor traffic between. Enniskillen, although distant some twelve miles, appeared to be the best centre, and here we were lucky in striking an extremely pleasant hotel—the Imperial. A further advantage of this town lay in the fact that it is readily accessible from Belfast by train, those of the party who were unable to use the cars being able to arrive in Enniskillen almost as soon as the rest.

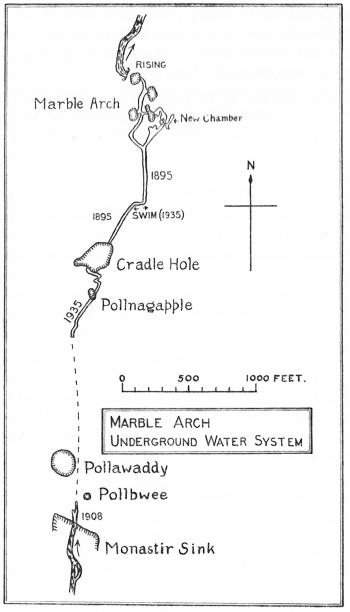

It is not proposed to describe in any detail the country in which the Cuilcagh group of caves is situated, since this has already been done. Suffice it to say that advice from Brodrick and Rule decided us to concentrate upon the system through which the Monastir River makes its underground course from its disappearance at Monastir Sink to its emergence at Marble Arch. The direct distance between these two points is eleven hundred yards—five-eighths of a mile—of which about six hundred yards was unknown up to the time of our visit. As will be seen in the following account, we were successful in reducing this unknown distance to about three hundred yards, a fair achievement for a short week-end under adverse weather conditions. With the above programme in view, we had obtained permission from Lord Enniskillen’s agent to have access to the Florence Court property, where the caves are situated. So on the Friday afternoon we called on Mr. Bowles, the head gamekeeper, who gave us a most enthusiastic welcome. He told us that not only did he well remember the earlier visits of members

of the Club, but that he had actually been present, as a boy, when Martel made the first exploration in 1895. He told us moreover that no serious exploration had been carried out since that of Brodrick’s parties in 1907 and 1908 ; in fact, the caves were hardly ever visited at all.

Under the guidance of Mr. Bowles, Junr., we made our way up the glen of the Cladagh (to which the Monastir changes its name) and started our first reconnaissance of the magnificent system of chambers and galleries constituting the cave of Marble Arch, guided by the plan to be found in Y.R.C.J., Vol. III., p. 64. After making a rough examination of the Balcony and the chambers lying between the open pots C and E, the Boulder Chamber was entered by L. Our guide told us that the route into the Pool Chamber had been blocked for some years past by a fall of rock and it took us no little time to work out a passage through the maze of immense boulders that formed the jam. But we accomplished it at last, and from there onwards it was easy going through Pool Chamber and Great Chamber to the Junction, where the river had to be waded knee-deep. We then passed rapidly upstream until stopped by the deep pool at the southern end of the Grand Gallery, finding somewhat to our surprise, that the beaches and sandbanks had not altered to any appreciable extent since the map was made in 1908.

On the following day two separate parties were formed, one to attack Marble Arch, while the other explored Cradle Hole. Conditions were disappointing, as a violent storm had raised the Cladagh considerably during the night, and when the first party reached the Pool Chamber they found it flooded to such an extent that delicate traversing along the walls was needed to reach the Great Chamber, while the Junction was unapproachable, water level being six to ten feet above yesterday’s. After making a thorough examination of the Boulder Slope and the stalactite passages at its summit, they found nothing new and turned their attention to the Pool Chamber. Here they were amply rewarded, for in the upper south-west corner a passage was found that led, first S.S.W. and then S.E., crossing above the passage from Pool Chamber to Great Chamber, finally ending at a ledge in the side of a cavern of considerable size. This cavern, which was surveyed on the Monday, was found to be about 70 yards long by 7 wide and 30 feet high. It lies with its axis S.S.W. and N.N.E. parallel to, and some 40 feet from, the passage between Pool Chamber and Great Chamber. The passage to this New Chamber ends, as mentioned above, in a ledge which runs along its westerly side, some ten feet above the floor, a rope being necessary for the descent. At the northerly end of the cavern, the floor of which is chiefly composed of mud, is a slope which rises to a belfry ; at the southern end the chamber turns approximately S.E. and is entirely occupied by a stream which disappears into a low bedding plane, in a north-westerly direction. This wet part was not investigated further, owing to lack of time. It is interesting to note that while on the Saturday the greater part of the New Chamber was under water, by the Monday the floor was reasonably dry. The edge of the northern flood had been covered with earthy scum and bore a most dangerous resemblance to dry land.

While the first party was in Marble Arch, the second descended the open Cradle Hole and entered the Lower Cave. Owing to the flood, penetration to any distance was impossible and when our attention was turned to the Upper Cave this was found to be even worse, no entry of any sort being achieved. The party therefore proceeded to investigate Pollnagapple, which was found to be a large open pot, some 60 feet deep, the descent of which, among moss covered boulders, presented no difficulty. The chamber at the base was examined and at the entrance, in the S.E. corner of the open pot, a small hole was found, surrounded by loose rocks. After several of these had been rolled away, a descent was made to a bedding plane, some 10 feet below, along which a 20 yard crawl in the south-westerly direction led to a rift where one could look down into a chamber below, in which a considerable stream was to be heard. The pitch looked awkward, so the steel ladder came into service and a descent was made. This landed us into a most impressive cavern on a bridge over a stream of such size that it could be none other than the Monastir on its way to Upper Cradle Hole Cave. We remembered that Brodrick, in his account of this latter, stated that he had been forced to turn back from lack of time, while the going was still good in an upstream direction. We felt sure we had landed somewhere near the point reached by him, so turned our attention to exploration downstream. (On Sunday the river was also reached by a shorter and more difficult route through boulders from the same entrance).

After crossing the stream the end of the chamber was reached where the water passed under a low arch. This temporary obstacle was turned by a traverse upwards from the right bank, through a short high level passage and so into the next chamber. Leading from this was another passage that branched, the left-hand route leading back to the stream, where further progress was impossible, while the right-hand passage led to a window high up in the rift along which the stream flowed. This right-hand route can best be described as a drain-pipe crawl along a tunnel, the floor, sides, and roof of which consisted of extremely sharply fretted limestone, suggesting that at some time past it had been completely filled with a stream of such slow current that the limestone suffered corrosion with but little erosion. From the window at the end a very faint glimmer of daylight could be discerned far down the rift, showing that what was undoubtedly the entrance to the Upper Cave in Cradle Hole had very nearly been reached. Subsequent examination on the following day, when lower water permitted wading from Upper Cradle Hole, showed that this supposition was correct and thus the course of the main stream from Pollnag-apple to Cradle Hole had been proved conclusively.

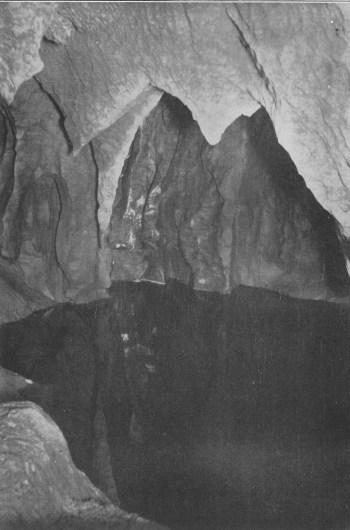

We next turned our attention to the passage upstream of the ladder route from Pollnagapple. The ladder ended on the left bank at the south end of the chamber, where the river emerged from under an arch and recourse had to be made to a traverse upwards through a small high-level hole leading into the next chamber upstream. Continuing on the right bank through this chamber and by a similar hole into a third, the river was then crossed by a remarkable cantilever bridge of stalagmitic material (or perhaps eroded rock), the two arms of which had not quite joined in the middle. Skirting the river on the left bank for some fifteen yards a boulder beach was reached, after which there was nothing for it but to wade in the stream. The water becoming deep, a crossing had to be made and on account of the depth and rapidity of the current, we roped up for this manoeuvre, advantage being taken of a diagonal ridge of rock that formed a kind of weir across the stream. We landed on a rocky shelf and in a few yards most of us recrossed the stream by wading once more, although two of the party managed to reach a bridge by a tricky little climb near the roof. The route then led for some fifty yards along a narrowing shelf past some very fine gours of gleaming white calcite, until once more we were forced to take to the water. This rapidly deepened after a few yards and the tremendous watercourse, far bigger than anything in Yorkshire, seemed to close down round a curve to the right. Exploration of the end, which was renewed the following day showed that the stream entered from the west, either through a syphon, or possibly under a low arch, the water being too deep and too swift for us to get near it. It seems likely that the next reach of the river is similar to that which joins Marble Arch to Lower Cradle Hole Cave (vide infra), i.e., the river flows along a subsidiary joint between two master joints, with curtains of rock in its course. Whether this next reach is navigable or not at low water, remains for a future expedition to discover.

On returning to the surface it was decided immediately to have a second look at the Lower Cave, since the river was steadily falling. On this occasion we managed to get some way further, but were still stopped by the water filling the entire width of the passage. We did discover, however, by means of a candle on a raft, that the water made an exit under a low arch on the right with only an inch or two of head room above the surface.

On the Sunday morning, heartened by the less swollen condition of the Cladagh, we made an attempt to enter Monastir Sink, but found it completely unapproachable. After a brief glance at Temple Bawn—a dry cave just above the Sink with two entrances, one a walk—-we returned to Cradle Hole and managed to force a passage along the water course to the farthest upstream point reached on the previous day. A survey of the cave was made, shown on six-inch scale, and the total length from the Upper Cradle Hole entrance found to be 280 yards measured along the stream and 205 yards direct. This represents about half the surface distance between Cradle Hole and Pollbwee, the next pot on the way to Monastir Sink.

In the afternoon we re-entered the Lower Cradle Hole Cave and found that the water had fallen to such an extent that we could reach the end of the main fissure ; where the water had, on the previous day, passed beneath an arch with only a few inches head room, was now an arch under which it was easy to wade. This led into a chamber, flooded to a depth of some 4 ft. 6 ins., beyond which was another low arch. By wading breast-high, we were able to reach the arch, but nothing beyond could be discerned. We therefore anchored the candle raft at this point with a view to seeing whether it would be in view from the south end of Marble Arch. With all haste we returned to the surface and made our way into Marble Arch, passing rapidly to the Junction and up the Grand Gallery beyond. Great was our joy when, on wading into the deep pool at the south end, we could clearly see the candle in Cradle Hole, shining through a series of low arches. The character of the junction between the two caves was now apparent. Both lie in master joints and the river has cut a course along a secondary j oint between them. In this secondary joint, a series of short master joints have opened out into small fusiform chambers, with rock curtains between. At high water some, if not all, of these rock curtains dip under the surface, forming syphons, but as the water recedes, a through passage is left.

Having thus established optical continuity between the two caves, it seemed a pity that no one should actually carry out the through route in person, so two volunteers were found to swim the intervening distance. The current was strong and the water incredibly cold, but the journey was successfully accomplished without incident, except for the loss of his boots by one of the swimmers. It is naturally difficult to hazard a guess at the distance separating the two caves, but something like 30 to 40 yards seems to have been swum and waded. That evening in the hotel the party duly celebrated what was felt to be a good day’s work—the first achievement of the through passage from Marble Arch to Cradle Hole.

On the Monday, the day of our departure from Enniskillen, only the morning was available. The party again split up, some going to survey the New Chamber in Marble Arch, while others attempted to reach the underground course of the Monastir at an open pothole known as Pollbwee. Sixty feet of ladders were let down and a landing made on a steep mud slope leading to a deep pool. The sides of the pot were none too safe, and precautions had to be taken to avoid falling rocks. The bottom was thoroughly explored, but there is no way through to the stream.

But little remains to be told. The majority of the party left Enniskillen about tea-time, by car or train, to catch the night boat from Belfast. Those of us who went by car will long remember one incident on the route—an Orange gathering in a little town, where everybody seemed to be beating big drums with incredible fervour and producing the most amazing din imaginable. On the boat, we found the crowd worse even than on the outward journey, and some of the party found themselves in the hold among sheep and cattle. But it was a lovely night and a calm sea and so we landed at Heysham just before dawn, agreeing that the meet, both from the point of view of enjoyment and accomplishment, had been a great success.

Those left, who had a fine afternoon once we had gone and a glorious day on the Tuesday, report that the rising passed in the Cladagh glen discharges not a tenth of the beck they saw raging into Pollasumera, and that in the region north of Boho a fair road now climbs up to within 200 yards of Noon’s Hole.

Bibliography.

Martel (E. A.). Irlande et Cavernes Anglaises, 1897.

Baker (E. A.). Caving : Episodes in Underground Exploration, 1932.

Baker (E. A.), H. Brodrick, C. A. Hill and R. LI. Praeger. Cave Explorers in County Fermanagh, 1907 (Pamphlet).

Brodrick (Harold). Some Pot Holes and Caves in County Fermanagh, Y.R.C.J. Vol. II., No. 8. p. 291. [WebEd: This is a typo. It should be Some Caves and Pot Holes in County Fermanagh]

Brodrick (Harold). The Florence Court Caves, Co. Fermanagh, Y.R.C.J., Vol. III., No. 9, p. 49.

Brodrick (Harold), C. A. Hill, R. LI. Praeger and A. Rule. Cave Explorers in County Fermanagh and County Cavan, 1908 (Pamphlet).