The Giant

By J. M. Davidson

Once upon a time (I am tempted to begin my story thus because it all happened so long ago) there was a giant in the Alps. He is still there, raising his two heads high into the sky. His castle is built of sheer rock-walls surrounded at their base by treacherous moats cut in blue-green ice. No roads lead to his domain, no drawbridges ; only cunningly-hidden traverses span the moats. And, at the time of my story, access was obtained to the stronghold by a succession of long, curving, hempen ropes in place of the more secure, but less authentic, beanstalk.

The Giant is a creature of uncertain moods. Sometimes he will encourage adventurous spirits to approach him, to mount his shoulders and scramble to the top of his heads, and there he will delight them with his enchanting wonder-scene. At other times he will be in bad humour and suddenly lash himself into a passionate frenzy. Woe, then, to the reckless man who comes within his reach !

Despite the introduction, this is not a fairy-tale, nor even an allegory. It is an artless story of a day spent in climbing the Aiguille du Geant. And, moreover, one of the characters is our Editor—a man of unusually retentive and accurate memory—so that any fanciful over-statements would certainly not be permitted.

Before daybreak one fine morning in July, 1909, four friends—E. E. Roberts, the late L. J. Oppenheimer, the late Adam Fox and “A Fourth-man “—left the inn at Montenvers and took the path to the glacier. They came fresh from a series of happy expeditions, with high spirits that would not be depressed even by a falling barometer or by the warm night air which announced the arrival of the Foehn wind. Did it ever occur to them that this was to be a day when the Giant was not at home to visitors ?

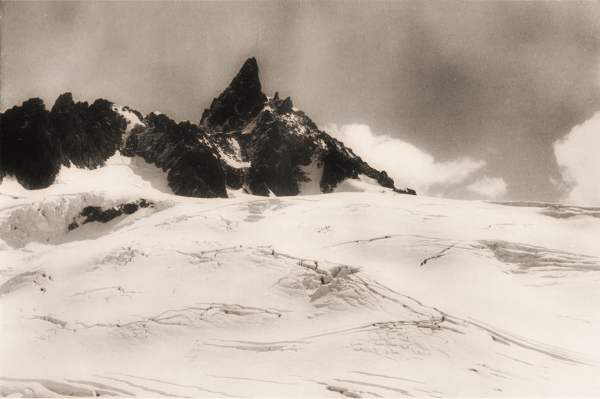

They advanced quickly up the glacier, so well-known to them, over the seracs, and then eastward to the snow-covered glacis of the stronghold. Above towered the Giant, black and clear-cut against the blue background of a cloudless sky. It was midday when they reached the snow-slopes—a late hour which, in the case of this mountain, has little importance. The summit rocks present the only difficulty of the ascent and they are climbed more easily when warmed by the sun.

The four climbers were on two ropes. First Roberts and Fox, and following them, Fourthman and Oppenheimer—an arrangement which was followed throughout the day. When the party had mounted the mixed rock and snow for a considerable distance, the second pair being close behind the leaders, the first mishap occurred. The top of a large slab of rock must have been resting in a state of very unstable equilibrium, for as the first man passed over, it became dislodged. In its fall it bumped slowly close to No. 3, but by that time its momentum was so great as to make his effort to check it quite futile. Oppenheimer, the last man, was at that moment mounting a shallow scoop in the snow directly in line with the fall. In the second or two, during which he realized the danger, it was impossible to move aside to safety, and the rock bounded through the air straight for his body. Instantly he flung himself down behind a small pinnacle of rock projecting a few inches above the end of the slabs, almost invisible from above and too small, indeed, to hide even his head from the helpless gaze of his companions. There was a crash—the mass had hit the projecting rock and had broken into two pieces, one piece bounding down on either side ! Oppenheimer, quite undisturbed,.continued his way upwards, with no worse hurt than two skin abrasions on his shoulders.

It was in a chimney above this that the fatal accident happened to Emile Rey, that ” greatest of guides,” whose physical collapse remains a mystery to his companion.

As the men approached the shoulder whence the real climbing begins, a white, eddying streamer was seen clinging to the top of the peaks and floating to the north. At one time it disappeared, but was soon seen again floating to the north-east and again to the north-west of the summits. Surely, the Giant had called upon the Foehn wind to signal that to-day he was ” Not at home ” ! Fourthman, who had climbed the mountain before, thought that discretion called for a postponement of the expedition. His companions, wishing to add a new peak to their lists, were reluctant to retreat. When they arrived at the foot of the rocks all hesitancy vanished. A descending party of two, guide preceding tourist, came swinging over space by means of a fixed rope, which was frayed until not more than one strand remained intact, down to our halting place. They reported that weather conditions on the peak were warm and windless, in fact perfect.

Our four men left their platform and, carefully avoiding the frayed rope, first climbed some rather difficult rocks and then followed a long and easy traverse leftwards. At the end of the traverse a succession of fixed ropes showed the way to the first summit. Climbing. directly upwards to the west arete and thence on slabs, in chimneys and on traverses, good progress was made in the warm sunshine. One member of the party, at least, refrained from touching the ropes and commenced a tirade against the immorality of spoiling a great climb by such unnecessary aid. What a danger he thought they might be ! Frayed by weather and by swinging in the wind, suspended from pitons driven into crevices and wedged there by bits of broken boxes, how easily some of these pitons could be withdrawn by a direct pull outwards ! . . . .

A brilliant flash and simultaneous explosion, that shook the mountain, stopped the discussion. A thick blanket of mist came with the thunder-clap. Every point and roughness of the rocks hissed at the climbers like hosts of angry vipers. Bzzz-zzz-zzz ! A wind arose, blowing now warm, now cold, charged with rain, sleet or hail. The two parties became separated, Roberts and Fox pressing on upwards after a necessary hold-up at the foot of an awkward chimney which rises from the end of a sensational traverse above an enormous slab. Over the first summit and down in the dip below the highest point the second pair met the leaders, who were now descending. Upward they hurried until a weird, dwarf-like apparition loomed through the mist. Two or three steps and they saw that it was a little image of the Virgin. She, too, showed her disapproval of the enterprise by adding her own to the chorus of hisses. The little aluminium figure, fixed on the summit by pious guides of Courmayeur, disfigured and dented by strokes of lightning, seemed herself a martyr to the tyranny of the Giant.

With scarcely the instant needed for an “Ave,” the two men descended into the hollow between the peaks and there decided to wait, under the shelter of an overhang, until the electric storm should pass. An hour went by. What an unforgettable hour ! Soaked to the skin, while the rocks hissed and the wind howled around them in their eyrie, Oppenheimer quietly talked of his beloved Lakeland, of his plans for the future, of his ambitions as an artist and his wish to retire from business in order to study painting in Montmartre. Alas ! his plans were never to be realized. A man gentle as fearless, he died fighting for our country in the Great War. But his influence is still with us and will last beyond the lives of those who were privileged to be his friends.

The hour went by. The rocks still hissed and the wind still howled. Instead of abating, the storm became worse and the rain had changed to snow. It was evidently not a mere passing electric disturbance ; descent must be risked. Oppenheimer led off along a narrow ledge leading to the first peak, a ledge which falls away sheer to the glacier below. As the shortened rope paid out, Fourthman stepped from under the overhang. Instantly, a heavy blow fell on his neck and shoulders; he barely escaped staggering over the edge.

” I have been struck, Opp., are you all right ? “

” I only felt quite a slight shock,” came the answer.

” My hair is on end and I am afraid for my hat. Does it make you feel like that ? “

For reply, Oppenheimer turned round on the ledge, bowed low and, taking his hat off with a sweeping salute, uncovered a very bald head surrounded by a close-cropped fringe of auburn hair. Both men had a hearty laugh ; all nervousness had vanished. There remained only fear and anxiety for the safety of their friends.

The two men arrived at the fixed ropes with changed ideas about the spoiling of the climb. They now called down blessings on the heads of the guides who had fixed the ropes there. Down they slid, both moving together regardless of frayed strands and insecure fastenings. A kick with the heel on the pitons as they passed—that was all. By degrees, as they descended, the rocks ceased their horrible hissing and only the storm and snow continued. No one can ever affirm, or deny, that this descent of 450 feet of cliff was a speed record. But, in what must have been a remarkably short time by the clock, though an age in the mind of the climbers, they were down to the shoulder. There they had a happy re-union with their companions, who had been waiting under an overhang of sorts in a state of grave anxiety, having almost given up hope for the safety of the belated pair. Plastered from head to foot with snow, Fox and Roberts as they descended the chimneys had felt shock after shock pass down their clothes.

It was now only helter skelter on the ropes down the great slab, a scramble down the snow-slopes, loose rocks, and glacier to the Rifugio Torino, where the climbers remained, weatherbound, for two nights and well into the second day.

This had not been the Giant’s “At Home Day ” and the gate-crashers had narrowly escaped summary vengeance.