IRELAND RE-VISITED: CAVES IN NORTH AND SOUTH

By G. S. Gowing

There is something about a club meet in Ireland at Easter that singles it out above all others as something worth remembering. Partly perhaps it is the sea-voyage, partly the different type of countryside, but above all it is the fact that spring always seems so much more advanced on the other side of the Irish Sea.

In 1936 winter was hardly over on the Durham Coast—the ski still rested against the wall of my garage, ready for use, instead of being tied up among the rafters. And as I drove across to the boat at Heysham, by Northallerton, where I picked up the Editor, up Wensleydale through that mysterious belt of mist that always seems to hang across the valley just beyond Leyburn, the countryside became progressively greener. But the following day, driving from Belfast to Enniskillen, there was an even greater difference and primroses were peeping out of the hedgerows.

We were taking a car with us, as Roberts and I proposed to go south to Clare after the meet at Enniskillen. So we had to be early on board the mail boat and we dined together in the little saloon, served by the same waiter who attended us last year. We turned in early, for want of anything better to do, and the next thing I, at any rate, heard was the rattle of the winches and the cries of the stevedores as our cargo was unloaded at Belfast.

Breakfast over, we went in search of the rest of the party, which had come aboard late the previous night from the train. We found them just packing into the hired car that was to take them to Enniskillen, the same car that we hired last year, a little older, a little shabbier and with the same vibration in the transmission, but even more shattering than before. Soon both cars were on their way to the west and lunch-time saw us in the Imperial Hotel, discussing the programme for the afternoon. Unfortunately, of the 1935 party, W. V. Brown and four of the Billingham men were unable to come, but Fred Booth, Roberts, Nelstrop and the writer were joined by Charles Burrow and Harold Booth, although the latter was unswerving in his determination not to leave the light of day.

So the six of us set off along the familiar roads, this year with considerably improved surfaces, and after greeting Mr. Bowles and getting from him the key were soon walking up the Cladagh Glen. Our objective was an opening near Monastir Sink, swallowing a small stream the direction of which, together with the configuration of the surface, held hopes of an underground confluence with the main River. So in we went and after the many twists and turns of an exceedingly narrow passage, we arrived at a rift some twenty feet deep. An awkward little traverse led past this to a point at which daylight could be seen, but no amount of wriggling, even when aided by excavation from the surface, sufficed to make an easier route by which a ladder could be brought in. So we gave up, with the full intention of returning later in the week-end ; which we never did, because of greater attractions elsewhere.

The water in the Cladagh was as low as it well could be, so on the Saturday the five explorers made straight for the New Chamber in Marble Arch Cave. Down into the ruckle in the Boulder Chamber there are many routes which appear to be dead-ends and it is worth noting that the most certain is to keep hard left. This brings one into the passage to the Pool Chamber by a greater and more uncomfortable distance than the best route, but it gives an opportunity of crawling along its prolongation, which falls slightly to a pool in a muddy bedding plane.

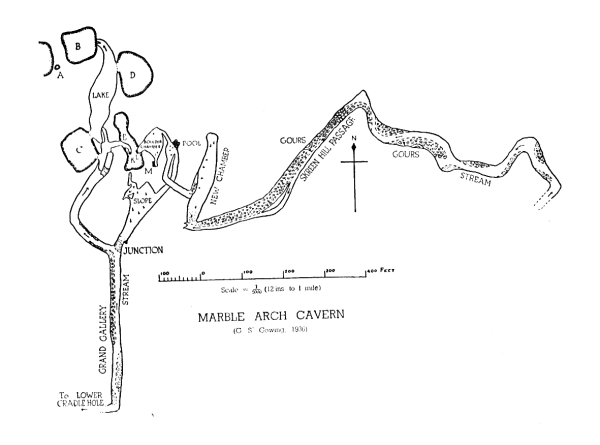

Reaching the New Chamber, where last year we had been confronted by a raging torrent was now only the merest trickle, and on turning upstream a striking passage was disclosed. This passage is rarely less than 30 feet wide and at least as high until the very end of its 400 odd yards and we were soon hastening upstream to see what new things we could discover. Starting from the chamber, the passage runs E.N.E. with galleries on each side at an old stream level. At the first corner the stream flows in an ox-bow almost entirely separated from the main passage by a rock curtain. Turning now N.N.E., the passage is nearly filled with a scree slope forming the right bank of the stream and here we passed some fine gours at the base of a cascade of tufa coming from an apparently large cave some 20 feet above the floors ; near by hangs one of the best stalactites in the cave, depending some five feet from the roof. At the end of this reach is a boulder jam, which is readily climbed, and then the passage turns E. with the stream meandering from side to side, but still nowhere of any great width. More gours are passed and then the character changes, the floor becoming more level with a consequent widening and deepening of the stream into large, nearly isolated pools. Several lengths have to be waded to a depth of three or four feet until, at a final sandbank, we reach a lake where one soon wades out of one’s depth.

We named this passage Skreen Hill Passage, as it runs approximately under a hill so named on the 6-inch map. The problem is—where does the stream come from ? As we saw it this year it was a trifling thing, but on the previous visit it was a river of no small dimensions. Since it appears to lead in the correct direction, there seems a considerable probability that it is the river that sinks at Pollasumera—there is a dry valley leading from this sink to Skreen Hill, a piece of evidence that may be, however, entirely misleading. It has previously been reported[1] that the stream from Pollasumera re-appears at the ” springs ” in the Cladagh Glen ; but having seen both during flood there is no doubt that the water appearing at the latter is only a fraction of that disappearing at the former. The other interesting problem is—where does the water go to after leaving the New Chamber ? There seems little doubt that it must join the Cladagh somewhere in Marble Arch Cave, but where ? It is true that a trickle appears from the wall near the Junction in the old cavern, but to us it appeared decidedly smaller. Only an extensive visit and plenty of fluorescein can answer these questions beyond doubt.

After our discovery of the new passage, the party went to the Junction and out by the river, Nelstrop leading the way into the long pool and proving that, under these conditions, it is not particularly deep. Off we then went above ground to Cradle Hole and into the Upper Cave. First we went downstream under the great choke and found the passage soon closed in a splendid belfry, floored by a round pool, eight feet below. Then in a body we marched upstream through the great pool which so nearly stopped us in 1935, wading in places where previously we had been forced to climb. Even the final reach, which we had managed by climbing precariously along ledges, could now be waded ; and so bit by bit we made our way into the middle of the final lake, ahead of the farthest point reached last year. We could hear the water ” glugging ” where the rock wall appeared to meet the pool, but still no one was entirely satisfied that something could not have been done with a boat, and many were the regrets that one had not been brought.

The thermometer had registered 45° F. for the temperature of the water and at our best paces in the cool atmosphere we set off for Monastir Sink. The cave was entered, the pool waded ana found to be a dead end ; then back to change clothes by Marble Arch. Booth and Nelstrop, however, report the existence of a passage high up at the dead-end, which might be reached by a difficult climb.

Harold Booth had, in the meantime, climbed Cuilcagh, the mountain on which rise the streams we had been exploring. It proved an excursion we should all have liked to have made.

Saturday evening’s discussions had closed with the decision that at all costs the Skreen Hill Passage must be surveyed, so on the morrow Fred Booth and the writer spent several hours with chain and prismatic, the while Nelstrop filled the air with echoing explosions and billowing clouds of smoke which reverberated and rolled along the passage—with what results can be judged by the reader. During this time Roberts and Burrow explored the old cavern, reporting that the confused area off the descent from ” E ” to the balcony entrance in ” C ” does not lead to the stream but to a view down through cracks, presumably in the roof between ” C ” and ” D.” A ball of paper on a string would settle this. A dry bit of the main channel above the place of climbing on to the balcony was found to be due to the stream from the big pool undercutting the right wall and forming singular pillars in the area, reminiscent of the frontispiece to Eaux Souterraines. (The letters refer to Brodrick’s plan, Y.R.C.J., Vol. Ill, p. 64).

We all met at the far end of the new passage and then Nelstrop donned a life-belt and swam upstream to the full extent of an eighty foot rope. He could find no sign of a landing and stated that, although the roof was undoubtedly approaching the surface of the water, there might be a chance for a boat.

The day finished, for the Editor, ingloriously ; for he allowed himself to be photographed for the press by two photographers who had followed us from the Imperial Hotel. Fortunately the photos were either not news, or too dreadful, for they never appeared, at least to the best of our belief, in the Belfast Daily Telegraph.

On the Monday, aU but the Editor and his assistant were seduced by the fine day and the attractions of Lough Erne. They refused to come caving, and instead, apparently, went bone-digging ; for it is reported that they unearthed a skull on Devenish Island ; which is not altogether surprising, in view of the fact that there is an old churchyard there. So we two set off and, for a start, had a look at.Cat’s Hole where we merely confirmed Baker and Brodrick’s reports. Half an hour was enough to exhaust the possibilities of this place, so we turned our attentions to Pollasumera. The beck was disappearing long before the cave entrance and we went rapidly along the 90 yards of passage to a choke of branches. In the area to the left we found Brodrick’s pool dried up and beyond it a maze of low passages and bedding planes that no doubt fill to the roof in times of flood. Around here we crawled for a long time, but could find no trace of a river passage, as might well be expected from the fact that the whole area is subjected to flooding. On coming out we found the weather distinctly colder and in fact had to make our way to the Cladagh Glen through a succession of hailstorms. Had we known it, this was a warning that England’s cold Easter weather was coming over to Ireland.

The morrow was a pleasant morning as we left Enniskillen, but a drizzle had already set in as we passed, with the usual delays, the Custom Station at Belcoo. Beyond, in the Free State, Eire now, the roads degenerated into narrow winding lanes, with appalling surfaces ; so much so, that by the time we reached Sligo we were wondering whether we should reach our destination in County Clare the same day. But from Sligo the Dublin road made our spirits rise somewhat and we made good time until we left it to drive south across Connaught to Galway. Here the roads were indescribable, but fortunately their straightness enabled us to keep up a good speed, praying for the car’s springs to hold out. Several times we went astray, misled by signposts that had been bent round to point the wrong way—Irish humour, one supposes. The country was dreary in the extreme and we realised that the great central plain of Ireland extends much farther to the west than one normally imagines.

Beyond Tuam, roads improved and the country was less forbidding and by Galway, where we had tea, the rain had stopped. Then we had the sea-coast and a winding run of 40 miles over limestone country, finishing in a long hill up to the downland country among which Lisdoonvarna lies.

Lisdoonvarna is a queer place; a little village of about 300 souls set in a completely treeless, desolate land, its spas bring thousands of visitors to its dozen or so hotels in the season. But out of season it is dead, and all its hotels are normally shut. Lynch’s Hotel opened, up for us and for a party of speleologists led by Pick of Leicester, who were visiting for the second successive year. We were greeted by them with acclamation and anxious enquiries as to whether we had brought any tackle, for all theirs was still somewhere en route from Dublin on an Irish railway ! The need for tackle sounded promising and after an immense dinner we all sat round a peat fire and listened to wonderful tales of this country of caves.

Our first expedition was a pot, discovered by Pick’s party some few days before. It turned out disappointing, merely an eighty foot shaft with nothing at the bottom. Some local farmers watched our descents with amused interest and it was from the chaff interchanged between us that a name emerged for the pot—Pollnapooka or Fairies’ Hole. The locals said it was called Poulnagollum (hole of the doves), but this appears to be almost a generic name both at Lisdoonvarna and Enniskillen and should be reserved, by long usage, for the large pot on the slopes of Slieve Elva, which that afternoon Pick, Roberts and I went to see. This other one is really a fine pot, nearly as large in area, and certainly deeper, than Cradle Hole. From there we wandered on to Poulnaelva, with which Baker guessed it to be connected, and then walked back across the summit of Slieva Elva, a fine Yoredale mountain with grand views over Galway Bay to the Aran Islands and the Atlantic.

On the following day Roberts and I turned our attention to Poulnagollum with the intention of checking some of the measurements and confirming, or otherwise, Baker’s suggestion that it is joined with Poulnaelva. We had to use a 90 foot rope as a handline down the sloping tree-covered upper part of the pot, and then the steel ladder for the final vertical pitch. Lacking a belay on the lip, we tied the ladder to the rope, to our no small discomfort, owing to the stretch in the latter. At the bottom of the open pot, we went straight in along the narrow winding stream passage, chaining as we went for two solid hours ; it seemed interminable, as we splashed through pool after pool, chain-length after chain-length. We passed a high tributary waterfall at 350 yards and then, at 1,560 yards, we arrived at a junction, which we assumed to be that of the so-called Poulnaelva branch. With relief we flung down the chain and carried on, worn-out but unencumbered. The character of the passage changed at last from rift to bedding plane type, the roof came down, and leaving the exiguous water channel to the right we took to our bellies. When Baker came here in 1925 this bedding plane was probably under water.

Through it we soon came out again into the main channel, still spacious but now with a lower roof. Roberts crawled back up the contracted portion. Presently the stream disappeared into the right bank, and soon after the dry passage forked repeatedly. The continuous route led us steeply down over gours, the lower stages stained with the reds and browns of iron. There we wriggled our way through boulders, the walls closed in and we were at the end. It took half an hour to return beyond the crawl. On careful comparison with Baker’s account there seems to be but little doubt that both we and Bartlett’s party went beyond his furthest, and both parties reached the same point.

Returning to our junction, we set out for the entrance, for the day was getting on. We were pretty well drenched and the water was only 41° F. (by thermometer, not guess), so we hurried forward as fast as we could go. Suddenly we heard the roar of water and then were confronted with a waterfall, certainly not the one we had passed on the way in ; and with the waterfall came the end of the passage ! Where were we? What had happened ? Then it dawned on us that our junction was not Baker’s but beyond it; that hurrying back, we had repeated exactly the same error he had once made, and were now at the end of the Poulnaelva Branch. Fed up as we were, we realised that we had at least got some good from our mistake, for there was no sign of daylight and anyway both distance and direction proved that this point was nowhere near Poulnaelva. So we carefully retraced our steps and found without much difficulty the point at which we had gone wrong ; we had missed Baker’s junction on our way in by hurrying through a low wide crawl in our anxiety to avoid a wetting ; on the way back, already wet through, the highest and most obvious waterway seemed the most natural route and we had turned up the side branch. An hour’s hard going brought us to the ladder and soon we were changing into dry clothes in the biting wind on the top of the pot. When Baker and Kentish first did Poulnagollum there were many gravel dams. Heaven be praised, broken by traffic they and the worst pools have mostly disappeared.

Space does not permit of much account of the rest of our expeditions from Lisdoonvarna. One off day we had, when we admired in glorious sunlight, the magnificent cliffs of Moher, where the Yoredale rocks stand over 600 feet sheer out of the Atlantic (see Kentish’s photo, Vol. IV p. 136). Saturday morning, chilly and wet, was spent exploring Poll Dubh ; in the afternoon we tried in vain a little cave on the roadside between Lisdoonvarna and Fisherstreet. At the latter village we struck Bartlett’s promising looking open pot; but alas ! it was the local charnel house and our ladder ended on the remains of a cow ! A pity, for at the bottom was a bedding cave with a little stream running merrily towards the sea.

The necessity to return came all too soon and the week-end saw us heading, half-frozen, north west across the centre of Ireland. Of how we saw, in the cold rain, the Seven Churches of Clonmacnoise, of how we failed to find the Sheela-na-gig at Abbeylara, of how we spent the night at Athlone, space will not permit me to tell. Suffice it that after an uneventful and unusually calm crossing, we learnt at breakfast at the Hill Inn that the weather in England had been far worse than what we had in Ireland, a. fact which gave us some consolation for we had thought our weather cold enough.

Bibliography.

For Northern Ireland, see Y.R.C.J., Vol. VI. p. 328.

For Southern Ireland :—

Baker (E. A.). Caving, Chap. VII.

Baker (E. A.) and Kentish (H. E.). Cave exploring in County Clare, Y.R.C.J., Vol. IV, p. 128.

Bartlett (P. N.). County Clare—A Brief Diary. Y.R.C.J.. Vol. VI, p. 329.

1. See Brodrick, Y.R.C.J., III, p. 51. “We were informed by-Mr. Bowles that he had seen his father put chaff into the stream (i.e., Pollasumera) and it had come out at the point marked ” Springs ” in the Cladagh Glen,”