OMUL : OR ” GETTING FIT FOR WAR.”

By H. G. Watts.

In August 1939, I was sent to Roumania as a member of a small Military Mission. There were five of us, and we had to carry out a reconnaissance of the oil wells and refineries round Ploesti. It was thought that the Germans would try to grab them as soon as they had settled Poland. Had Russia not stepped in and seized the common frontier that is un doubtedly what they would have done. We wanted to be in a position to put them out of action first, but the war hung fire for so long that nothing could be done about it in the end. We stayed in Roumania till October 1940, waiting for something to happen, and were finally withdrawn rather hurriedly while the German Army was marching down the Prahova Valley to Ploesti.

Life was very pleasant in Roumania. Bucharest was gay and cheap ; you could entertain half a dozen friends to a seven-course dinner with cocktails, wines and Napoleon brandy, at Capsa, the ” Monseigneur” of Roumania., for £3 10s. all in.

In spite of all the counter attractions we worked hard, and at the week ends we kept ourselves ” fit for war,”—in other words we worked off the liver acquired during the week. Still, we never forgot that we might one day have to swim the Danube to Bulgaria. So on Saturdays we shot off up the King’s Road (the only decent one in the country) to Sinaia and the mountains.

My introduction to the Carpathians was on 14th October, 1939, when Taffy Wilson, with whom I was staying, came in at lunch time and announced that Monday, the 16th, would be a public holiday in honour of King Carol’s birthday, and wouldn’t it be a good idea to go to the mountains and get three weeks’ smoke and tsuica out of the system. (Tsuica is a rather unpleasant raw spirit made from pears or plums, and much favoured in those parts.)

We went in to Wilson’s car to Sinaia, a mountain resort, rather smart, in time to play golf on Saturday afternoon. The king had a country house there, and Madame Lupescu a villa, in which she spent a good deal of her time. There is a casino. I bought the best pair of ski-boots I have ever had, beautiful soft leather, and big enough to take three pairs of socks, for 1,500 Lei (2,000 Lei to the pound sterling !)

We started up the mountain after breakfast on Sunday, past a very Byzantine monastery church, and the king’s summer palace, half-timbered like a Bavarian hunting lodge, all pointed turrets and stags’ antlers. Then through beech woods, with the leaves turning a most beautiful brown and gold and yellow. After an hour’s climb we reached a sloping open meadow called the Poiana Regale or Royal Meadow. We were to get to know this well later in the year ; when the snow fell we made it our practice slope, and the following spring it was to shimmer with myriads of mauve crocuses.

Presently the beeches gave way to larches and Austrian pines, and when we had been climbing for two hours we got above the tree-line on to a high grassy plain with strange dwarf pines, none more than four feet high, growing on it. The Carpathians are not like the Alps, they are mostly of limestone, and although the mountains rise sheer out of narrow valleys, and look rugged and craggy from below, at the top they are flat and grassy, like Helvellyn.

We took enough food with us for two days, because, although there are plenty of huts, staffed and victualled by the Roumanian Touring Club, Wilson did not seem to think much of the quality of their food. So in addition to our tooth brushes we were carrying a large loaf of bread, some butter, a salami sausage, a Gruyere cheese, 12 apples, a box of biscuits, 1 Kg of ham and a tin of herrings.

We lunched at a military hut, the Cabana Mihai, at the top of the climb, off cheese and salami; the soldier on duty found us beer. On the way up we had overtaken a German family, father, mother and two pretty daughters. The father was the Ploesti agent of a German firm, and a well known Nazi. However we passed the time of day and were all very polite to each other. We were still in the ” no personal enmity against the German people ” phase, particularly in the mountains.

After lunch we crossed the watershed till we could, look down into the Ialomitsa Valley, lovely, green, isolated, with a little stream, like the Goyt, tumbling down it. I went to that valley many times afterwards ; it always reminded one of James Hilton’s ” Lost Horizon.” To get down we had to scramble through a dense forest of immense pine trees, with long trails of pale green moss hanging from their branches, giving the place a mournful and sinister look.

At three we got to the hut, the Casa Pestera, where we were to spend the night. It was in an open grassy space near the Ialomitsa river. We were rather put out to find that we were not greeted with the hospitality usual in mountain huts, that there didn’t seem to be much furniture, or any food in the place, and that the entire staff, and several other people besides, were standing on the verandah, all talking at once, and running round each other in small circles.

Wilson, who spoke Roumanian, went off on a recce, returning a few minutes later with a bottle of wine and the information that the hut was in process of changing manage ment, and that the incoming tenant, his chattels, his wives, sons, daughters, ox, ass, hens, turkeys, geese, ducks and dogs, about half his furniture and none of his food, plates, or cooking utensils, had arrived on the scene about half an hour before us, accompanied by three officials of the Touring Club to see them safely settled in.

Casa Pestera is at least eight miles from anywhere, and that’s over a mountain, and it isn’t connected with anywhere by any kind of road, track, teleferica or navigable waterway. So we dumped our rucksacks, hoping for the best in the fulness of time, and went to look at a monastery.

The river Ialomitsa rises by issuing from a limestone cave, into which Wilson says one can penetrate for J mile, at which point the surface of the water meets the roof. At the mouth of the cave there is a little monastery consisting of a tiny Greek Orthodox Church, in a little courtyard, with a cloister round it. Five monks live there, had just heard somebody in the village say that there was a war on somewhere.

On the other side of the stream, tucked away in the woods, we found another little church, from which we could hear sounds of chanting, and presently we saw the old bearded priest looking at us out of the window. We chatted with some peasants for a while, then the old priest came out. He said ” Seara Buna ” to us, and talked to Wilson for a bit in

very good and educated Roumanian, saying that he hoped we would be comfortable at the Casa Pestera, and that he was even now on his way to kiss the hands of the new tenants and to bless the house.

When we got back to the hut we found that not only had they made up two beds for us, but that a packing case con taining plates, knives and forks, and cooking utensils, had arrived on a carutsa (farm waggon). It is a mystery how the carutsa ever got across country, but the important thing was that it did. What was more, the new landlord said that he could make us an omelette with our ham, and some eggs which we could only think his hens had laid in the carutsa on the way up, but the rest of the meal we would have to provide ourselves. What a mercy it was that we had supplied our selves so lavishly in Sinaia !

Finally we did very well, the ham omelette was marvellous, and they really do know how to make tea in Roumania. Also they produced another bottle of red wine, and the rest of our dinner consisted of bread and butter, salami, and apple and cheese, the last two an excellent combination, very popular here.

All this was eaten by the light of one small paraffin lantern on the other side of the room, where the members of the Touring Club were going through the contents of the medical chest, with the landlord. Something in the chest, probably indecent, seemed to cause them great amusement.

The only other guests were a German couple from Bucharest who were very upset to find no food available. In the end the landlord made them a stew of some kind, and we gave them some of our bread, for which they were pro foundly grateful, in excellent English.

As there was no light, nothing much to sit on, and very little company, we went to bed at 7.45, and found that those good people, in spite of all their worries of moving in, had lighted a stove in our room for us. Our sleep for some time was disturbed by imaginary insects, for which Wilson says he has a fatal fascination, but we slept well enough after we had decided that the insects were only imaginary.

On Monday morning we washed and shaved in the river, which can’t have been much above freezing, as the water came either out of the limestone, or from snow melting in the higher meadows. The sun was shining and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, so we decided to climb a mountain called Omul (The Man). Wilson said it was 10,000 ft., though the maps (very unreliable in Roumania) give its height as 2,511 metres or 8,238 ft.

We had another ham omelette for breakfast and started serious climbing at 9 o’clock. In the lower meadows the peasants, wearing white leather embroidered waistcoats and pointed black woolly hats, were collecting the sheep to drive them down to the banks of the Danube for the winter. The journey of about 100 miles takes eight days to complete on foot.

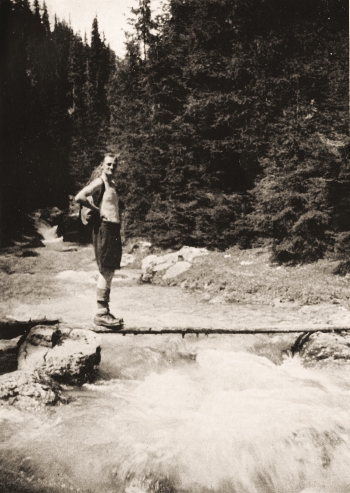

The second hour was hard going up a steep, rough path with occasional large patches of melting snow from a blizzard the previous week. The sun beat down fiercely, and we discarded one garment after another. The ground where the snow had melted was a carpet of Alpine plants, unfortunately not in flower at this time of the year. I recognised Alpine roses, yellow geums, and a pale blue gentian.

The last 45 minutes of the three hour climb was like most mountain climbs ; one sees the hut at the summit, one smells the wood fire burning, one thinks of that first gulp of cool beer, but how slowly the hut seems to come nearer ! The rush of hot, steamy, food-laden air made us stagger as we opened the door, and we persuaded the people to give us our tea and beer outside in the sunshine.

Omul is one of the highest peaks in the Carpathians; the summit used to be on the frontier between old Roumania and the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918. We could see the undulating countryside of Transylvania to the north, the flat Danube basin to the south, and the snow-capped Carpathian peaks fading into the distance on either side.

The way down was through a steep narrow valley, the Valea Cerbului, where the snow still lay in deep drifts, and where we sank to the thighs if we tried to walk down in the normal way. The only way to tackle the drifts was to run down them at full speed hoping not to fall over. On either side the crags rise sheer in great pillars of rock reminiscent of the Dolomites, offering irresistible temptation to the moun taineer. When we got to the decidous tree line the sun was shining through the beeches, and everywhere seemed to be bathed in bright yellow light, with occasional larches giving a background of bright green.

At one place we roused the curiosity and resentment of two shepherds’ dogs, wolf-like creatures with sour tempers and a deep suspicion of strangers. It is always advisable to carry a stout stick and be ready to throw stones. The Roumanian dog is at heart a coward and will run away if one shows fight, but he has a nasty habit of sneaking quietly round behind and taking a piece out of the calf of the leg. That means an unpleasant and prolonged series of anti-rabies injections, to be avoided at all costs.

It was beginning to get dark when we reached the village of Busteni, on the main road and railway. There was just time for beer before catching the train back to Sinaia.

After this introduction we got to know the mountains well in the Sinaia, Predeale and Brasov districts. The snow came permanently towards the end of November, and from the week-end before Christmas 1939 to the beginning of May 1940 we never missed our weeldy ski-ing expedition. We had, after all, to keep fit for war.

In spite of all the attractions however, the homesick Briton looks with a prejudiced eye on the foreign field when exile is prolonged and unsought, and when there lurks a possibility that a corner of that field may become permanently his. The Craven district still remains unbeatable, except possibly by the Scottish borderland. Notwithstanding the beauty and delight of many strange places, they seem to be delightful only for about four weeks in the year, at other times they are either too cold (the Englishman’s great discovery of the late war) or too hot and fly-blown.