Two Climbs On The Chamonix Aiguilles, July, 1953

by C. I. W. Fox

The two climbs which I am about to describe were the high spot of an otherwise disappointing season. With Bill Kelsey and a C.U.M.C. climber, Neil Jackson, several marathon expeditions were undertaken on the Saas peaks by way of training. The very late season made these trips somewhat trying, and I can still hear (in my imagination) the avalanches crashing down either side of the Portjengrat as we made our way along the ridge. A descent on Zermatt via the Rimpfischorn revealed conditions so bad that we determined to follow the well-known advice of “Go West, young man.”

The East Ridge Of The Plan

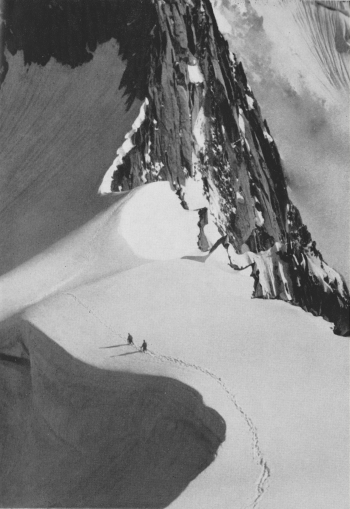

Early in the morning the steep little glacier below the Aiguille Du Plan was in good condition, and, in crampons, we quickly walked round from the Envers hut and then up into the glacier bay bounded on the left by the cliff of the Pain de Sucre and on the right by the Blaitière. Ahead of us the Plan Crocodile and Caiman formed the end of a huge cul-de-sac.

The glacier quickly steepened and then was slashed thrice by enormous bergschrunds. The first ‘schrund could be turned on the right but the second cut the glacier from side to side.

However, I had been up on the previous day on a reconnaissance of the Caiman and knew the secret. Making an ascending traverse right under an overhanging ice-cliff, we went to a cave formed by an overhang of rock on the extreme right (true left) of the ‘schrund. There a vertical ice-tunnel about 10 feet long led up or rather through the difficulty. This was so narrow that it was necessary to remove sacks to negotiate the obstacle.

Above the tunnel a steep slope of firm snow led to the foot of the third ‘schrund. Here, while the second man firmly belayed in good snow, the leader stepped across unstable bridges, clambered awkwardly up a slab of smooth projecting granite and then delicately stepped up ice steps over the vertical upper lip of the ‘schrund until he could belay to a convenient rock above. We were then clear of objective danger from the Plan-Crocodile couloir and could breathe more easily. We saw no stones falling although many were embedded in the snow below.

Shortly after this we took to the rocks and removed our crampons. Moderate and entertaining rocks led us quickly upwards until we came to the point where the route (which at first keeps to the right of E. Ridge looking upwards) at last goes straight up to the crest. The view from here was very thrilling. Across the couloir the slabs of the Crocodile’s east ridge rose steeply, beyond the Crocodile the monolith of the Caiman was rose-tipped with morning light, and below us the glacier was still in shadow.

Now the character of the climbing changed. In place of clean rocks we found everything plastered in snow. In between the rocks lay black ice, covered with powder snow. And the rock was unstable. I realised that we would have been better advised to go on the south side of the ridge on the alternative route which is cleared by the sun. The south side of the Plan-Crocodile couloir only receives about two hours early morning sun in a day.

However, we were now committed to the route like Smythe and Bell before us. It was, of course, necessary to clear the snow away and then beat the black ice into submission. Seldom have I felt more precarious. Occasionally we came to something really solid and great was our relief. Towards the end of our toil we had to cut delicate steps up a layer of ice overlaying slabby rock, being careful not to hit too hard for fear the whole crazy structure might peel off. This couloir occupied some three hours of our time and we were very glad when at last we stepped out on to the sunlit ridge.

Here, our situation was magnificent. Across the couloir to our left the Pain de Sucre N. face rose incredibly steeply and we could see the fantastic ice-route worked out by Greloz. Above us our route soared up like a huge fin into the blue sky.

According to the guide-book, this was where the difficulties started. Under good conditions the couloir should present little difficulty, but many parties seem to find bad conditions.

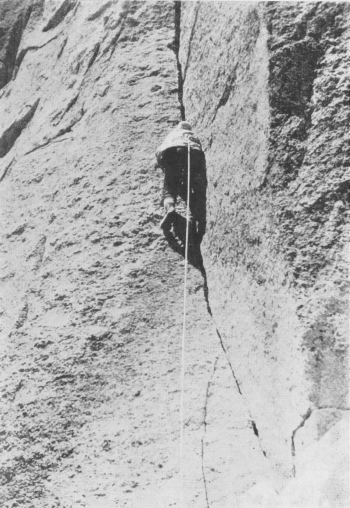

After a number of nice chimneys and cracks we were suddenly confronted by a savage fissure which swept up for some forty feet and then curved more steeply. We had arrived at the “Fissure de la Grand ‘Mere.” This curiously named fault proved less difficult than it looked although in common with all pitches on this climb it was strenuous.

From then on chimney followed chimney and crack followed crack all strenuous and some very awkward. We felt that our sacks were far too full and the expenditure of effort involved in hauling them up some awkward pitch was considerable.

Hard as the climbing was (it was rated at “4,” probably about mild severe), Neil evidently thought it too easy for he led us up a chimney which I thought at least ” 5.” The exit from this was one of the airiest things I have ever done. A magnificent pitch.

The climb keeps to the left of the ridge (looking up) for much of the way. Eventually it led us to a saddle where a high bank of snow provided refreshment.

After a slight descent another savage crack reared up. About eight feet up this a piton grew (after grasping it I would have said “bloomed “). Progress is made by jamming the fingers in this fissure and planting the feet on the rough granite at the side. Near the top another piton enables the leader to hook carabiner on for a running belay. A stirring pitch, but my admiration for Ryan and Lochmatter, who did this stupendous climb without pegs and in nailed boots, grew as we followed their wonderful route. Truly there were giants in those days!

A broad ledge eventually led round to the left and we knew from the guide-book that we were approaching the final tower. Belayed round a large boulder, the leader disappeared round a corner and the only sign of activity was the slow movement of the rope. A delicate move of “5” was indicated in the book and we wondered what was in store for us. However, this was not too bad, a long step to the left while holding on to a vertical fissure with the right hand. I find that delicate moves in the Alps are generally over-rated, at any rate from the British rock-climber’s point of view.

Several more chimneys led on and up until we came to a route finding problem. The guide-book said that the bottom of the next chimney was distinguished by a large detached flake but all the chimneys in the vicinity seemed to be so adorned. Eventually we went straight up an overhanging chimney using lay-back methods. This I found the hardest pitch of the chmb coming as it did at the end of such strenuous exertions. Of course, as soon as we were up it was obvious that a very much easier fissure round the corner was the correct route. Above this pitch the chimney went only vertically upwards (a great relief) for about fifty feet and then split into a Y. The way was by the left fork of the Y. To attain this it was necessary to make a curious manoeuvre in which one lay on one’s left side, planted a foot across into the right fork of the Y and shoved vigorously until traction was obtained up a sort of trough.

After a few more easier pitches we at last stood below the final tower, and a few minutes sufficed to put us on the summit. Here we three met up with Geoff Pigott of the Rucksack Club and Neil Mather who had been ahead of us all the way. Physically we were tired but very satisfied with a memorable and magnificent climb.

The ordinary way down went very swiftly, although the snow was soft. As we followed the well-trodden track, we kept looking over shoulders at the wonderful peak we had climbed, glowing red in the rays of the descending sun.

For future parties I would advise: climb in Vibrams, as we did. Pick a good settled day and travel light. Early in the season it might be advisable to go on the southern side of the ridge in the lower part; and reconnoitre the bergschrunds on the previous day. Finally ” train on raw meat and stout, wear bull-dog buttons.”

The Grépon By The Mer De Glace Face

For long this climb has been in the nature of an unattainable ideal and it was therefore with some surprise that I found myself with George Spenceley walking up the tortuous path which leads to the Envers d’Aiguilles hut. The weather was fine, George was full of enthusiasm, while it was my last climb of the season.

We had determined to go up to the Tour Rouge hut in preference to the Envers, as the former is high on the face of the Grépon. The usual manoeuvres on the steep little glacier below the Grépon landed us on the rocks. On the way up another English party passed us on their way down, and we could not help thinking how typical they were of many “British parties” to be found in the Alps. They had done the chmb that day and returned the same way. Obviously, they were first-rate rock climbers. But when they got on to the snow their incompetence to cope with this medium was plain. Each man ran out 100 feet of rope before the other moved across traverses. Should any man have come off, the huge pendulum swing would have disorganised the party (to put it mildly). Apart from this the loss of time involved was considerable as they painfully progressed down. As Dr. Longstaff has often said, speed and safety are almost synonymous in the mountains.

A striking contrast was provided by two young Frenchmen who appeared round a shoulder of the glacier below and approached our position with speed. As we waited for the British caravan to coil its way past us, we observed with amazement these young stalwarts speeding up. When they arrived we saw that only one of them had an axe and sack. This arrangement is fairly common around Chamonix, although it must be admitted that it makes for less safety on snow and ice. On the other hand, the extra speed achieved probably lets the party arrive on snow section in reasonable conditions. Much must depend on their competence and nerve. I once saw such a party going down the Nantillons Glacier at a pace which can only be described as a full gallop. The man with the axe was last on the rope.

A vertical crack classed as IV landed us on easier rocks and we were soon peering into the squalid little shelter which was our home for the night. To our amazement four new blankets and a new mattress had been installed. We lost no time in staking our claim. The other end of the hut had a sinister looking pile of very old blankets which we did not disturb. The two French lads arrived shortly afterwards and preparations for a meal were soon under way. We were congratulating ourselves on our good fortune at having the hut to ourselves when one of us saw a party of four coming up the glacier below. Many and loud were the curses. Space in this hut is strictly limited. However, our fears were completely unjustified for the party of four French people were courtesy itself and our sleep was undisturbed.

Next morning, when it was light, we crawled out to observe the weather. This was by no means perfect, with low cloud swirling about. At length we decided to go on until we saw how things materialised, at least as far as the abseil into the couloir. Our optimism was justified as the weather improved when the sun rose and the clouds dissolved.

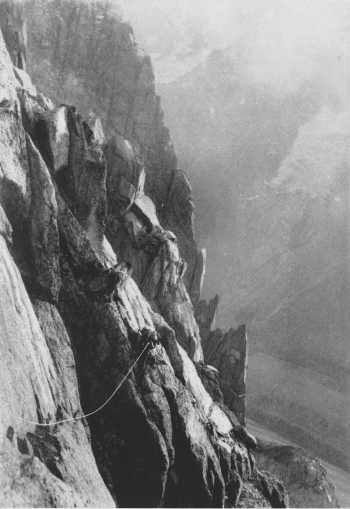

What a beautiful face this is! Charming little streams cascade down from small snow patches and the great sheets of slab sweep down cleanly through the sunlit air. Occasional patches of brightly coloured flowers relieve the austerity of the scene. The climbing was not unduly difficult and we could look around to admire the scene. The two young Frenchmen were ahead of us and going well. However, we caught up with them at a point where a traverse was indicated and it was necessary to look for the route. Here they tried to climb some extremely difficult rock, and as no difficulties were mentioned obviously the route was elsewhere. Sure enough, a traverse above a prominent pinnacle led over to the left on reasonable ground.

Traversing a large chimney which vanished steeply below our feet we landed on a broad ledge. Ahead of us a huge couloir blocked our advance. This was obviously the obstacle mentioned by G. W. Young and we began looking for a rock shaped like a milestone. This was readily identified as it had a necklace of slings about its “Shoulders.”

An abseil of about 30 feet landed us in the bed of the couloir. I traversed this and got onto a ledge at approximately the same height as our departure point.

Typical Chamonix cracks and chimneys led us upwards. The exposure was considerable but the climbing so engrossing that the rock seemed to charm us on to new heights. At length we arrived at the Niche des Amis where there were certainly plenty of “Amis.” The two young Frenchmen were up a vicious chimney which rose straight up and their voices floated down to join us. The other four French people (one was a woman) were munching chocolate and gazing earnestly at the chimney. Shortly afterwards progress again began and one after the other we grunted, swore and coiled our way up the fissure. The top part was decidedly airy, but one could protect oneself with running belays at several places.

After a series of similar pitches we arrived at a snowy shoulder. A passage of IV Supr. was indicated ahead. This was said to be delicate and we wondered what was in store for us. The pitch materialised as a shallow crack sloping from right to left, about 10 feet long and almost vertical in section. Some kind soul had planted a piton at the bottom and this dispelled most of the apprehension about the large quantity of fresh air which was immediately below. The pitch went easily however with a lay-back technique and landing was excellent on an earthy ledge.

Ahead of us the great chimney mentioned in the first ascent glared at us, and we marvelled at the temerity of the pioneers. It was hard to see, however, why they did not oblique to the left to avoid this pitch, as moderate rocks led off to the left via a broad ledge.

Along this ledge we walked and then climbed an open chimney back to the right again, where we emerged on a broad ledge which cut into the great chimney at half height.

The continuation of the chimney above this proved to be hard, but went well if one tackled it methodically. Near the top things got very thin and the few good holds were grasped thankfully.

We were now near to the Breche Balfour and the Aig. de Roc leered at us almost level with our heads. A rounded pinnacle caused a little bother until we tumbled to the technique of slinging a bight of the rope around its blunted snout and penduluming out to swarm over the further side. Our arrival at the Breche was signalled by a blast of icy wind laced with driving snow and, peering over the rocks we saw that black clouds were boiling up on the far side of the crest and the weather in general looked very menacing. A growl of thunder made us look apprehensively at each other, and although we went along and looked at the final crack, we knew in our hearts that the half-hour involved in getting up the glorious finish might well put us in a mess with the vicious storm obviously about to hit us.

So down we went by the C.P. route with the raw wind chilling us and snow swirling in our faces.

At the traverse over the knife-edge the conditions were so bad that it required considerable mental effort to face the exposed little bit of climbing on the far side.

Eventually we arrived at the Col des Nantillons and soon we were speeding down the glacier. Our judgment in not delaying our departure was amply proved as, when we had just got down to the easier portion, the skies opened and thunder and lightning interspersed with hail, snow and rain, lashed the heights about us.