Holes In The Ground

(Reproduced by the courtesy of the Proprietors of “Punch”)

The significance of the word ” rambler ” appears to have changed considerably since the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club was formed. It has had ample time to do so. That body is celebrating this year the Diamond Jubilee of its foundation. It has spent the sixty glorious years since 1892 in indefatigably clinging by its teeth to overhanging crags, swarming up wholly inaccessible pinnacles and plunging through torrents of cold water into vertical abysses. There is only one thing it has failed to do in those sixty years; it has never, in any normally accepted sense of the term, rambled.

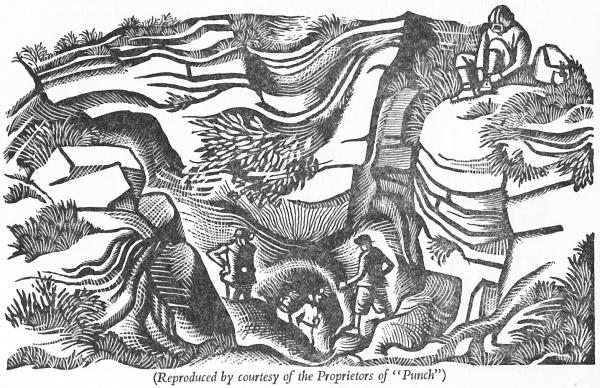

The Club’s activity, is, in fact, mountaineering. Its 160 members live all over the habitable world; but the centre of that world is, not unnaturally, Yorkshire. Now, Yorkshire is a county rich in all manner of Nature’s choicest products; but it lacks a supply of rocks of the kind esteemed by mountaineers. The Club has to travel, therefore, in search of such rocks, to the Lake District, Switzerland, Norway, the Andes or some other locality where they abound. This it does; but it is a long way to the Andes, and sometimes the members of the Club can only spare a week-end. They solve the problem by doing their local mountaineering below the ground instead of above it. The county is freely supplied with subterranean holes. These contain great quantities of unscaleable limestone which the members of the Y.R.C. scale in conditions of the most delectable darkness, dirt and discomfort imaginable.

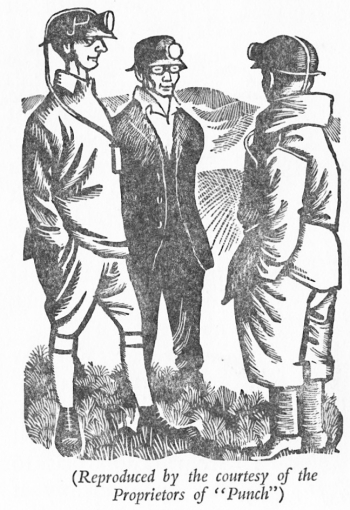

A word or two about pot-holes. A pot-hole is not to be confused with a cave. A cave is a hole in the side of a hill; a pot-hole is a hole, or a system of holes, in the ground. Most of the potholes are situated in the parts of the Pennines around Ingle-borough; they have delightful names, like Gaping Ghyll, Cowskull Pot, Jingling Pot and Boggarts’ Roaring Holes. They are descended by men of unusual calmness, amiability and muscular powers, equipped with ropes, rope-ladders, large boots with large nails, dungarees, and miners’ helmets bearing either electric or acetylene lights. A partial descent of Bar Pot was, however, accomplished lately by the writer, who lacks almost all these requisites. He owes the experience to the friendly invitation of the Y.R.C., and his life to their constant attention and support. Had he read, before going down, of the recent disastrous descent in the Pyrenees, he would have stayed resolutely above ground.

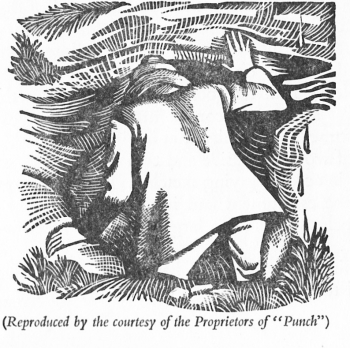

Bar Pot is a part of the Gaping Ghyll system. There are many such subsidiary means of access to the great main chamber of Gaping Ghyll, which can otherwise be reached only by lowering the sufferer down on a bosun’s chair through a waterfall. The writer, having gratefully accepted the Y.R.C.’s invitation, found himself standing at the bottom of a boulder-filled hollow in the moor above Clapham, Yorks. In front of him was a small mouse-hole at the foot of a limestone crag. Kindly hands placed a miner’s helmet on his head. The electric light in this particular helmet was very weak, so a further hght was slung round his neck. He then entered the mousehole feet first.

A cold wind blew strongly up the mousehole and cold water trickled steadily from its roof. It led down to a place where a man squatted by a narrow hole in the floor. He was waiting for the writer. He tied a rope round him and the writer stepped into the hole.

This hole is called a Loading Gauge. It serves to ensure that nobody with a waist measurement of more than forty inches can get into the hole at all. The writer is not in this category. He passed slowly through the hole, leaving his arms behind him.

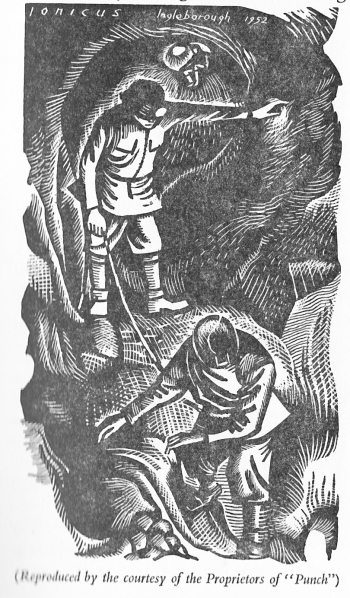

Below the hole his feet were waving about, knocking against rock walls but finding no manner of foothold. He sank till, looking down by his side, he could see a widening cleft below with an illuminated man wedged in it. The man advised the writer to place his right foot on an invisible ledge. The writer placed his foot on the ledge. It slipped off. This ledge moved upwards past the writer’s knee; but his left foot struck another.

The writer was now stationary, and supported, though insecurely, by one foot. It seemed a good place to stay, permanently if need be; but both the man peering through the Loading Gauge and the man wedged in mid-air advised him earnestly to proceed. Five feet or so below his feet a rope ladder issued from the rock. There were no handholds or footholds whatever between the writer and the ladder. He hstened patiently to a great deal of friendly advice, and at last decided to descend. The decision was reinforced by the sudden departure of his foot from its ledge.

After some confused passage of time the writer found himself grasping the upper part of the rope ladder, with his stomach wrapped round a rock and his legs waving in black space looking for a rung. The manner in which the descent from the Loading Gauge to the rope ladder was made is not fully known, but the technique used is believed to have been entirely new.

At the foot of the ladder the writer de-roped and descended a narrow and nubbly funnel, appreciably out of the vertical, for a hundred feet or so, till a great hole was reached. He was requested to crawl like a fly round the vertical side of this hole and through a tiny aperture in its far wall.

The aperture led to another chasm, obviously bottomless, and about twenty feet in diameter. Several men standing about the — edge of this chasm tied another rope round the writer’s middle and led him to the brink. Thirty-five feet down, they said, there is a ledge; step off there and have a rest before going down the next sixty feet.

The writer descended thirty-five feet to the ledge. His head-light was now completely extinct. The lamp round his neck warmly ihuminated the front of his jacket; a little tiny hght on the head of a man shone, sixty feet below. Otherwise all was darkness. Water dripped liberally upon him. If he stepped to the rear of the ledge the water became a torrent; if he stepped forwards he tended to fall off. He decided to continue the descent, and stepped back on to the ladder.

The ladder rotated smartly three times and deposited him on the ledge again.

The writer made nine unsuccessful attempts to get off the ledge on to the ladder and descend. The moment a downward step was taken the ladder bucked like a mule and shot him back on to the ledge. Distressed at the unhappy relations between himself and the ladder, he decided to reascend. Reaching the top of the chasm, he sat reflectively on a boulder, until he was at length moved to ascend to the Upper Air. In this he collaborated with the secretary, a man of immense strength, who hauled him bodily up the final pitch to the Loading Gauge.

As the writer was passing up the narrow cleft leading to the Loading Gauge, his remaining light, the one slung round his neck, was torn off by the circumjacent rock and flung into the depths. He finished the journey in complete darkness. His final discovery was that daylight has an overpowering and wholly delightful green smell. He had, he was told, spent four and a half hours below ground and been to a depth of about 200 feet. The pot goes down another one hundred and sixty.

Pot-holing, the writer decides, is an admirable sport for the young, strong, nerveless and elastic. It is also the only sport known to him in which one participant may remark to another, in complete seriousness. “Can I have a light from your hat? “