South Georgia

by G. B. Spenceley

One writer has described South Georgia as like the top ten thousand feet of the Alps set in a stormy sea. And that is how it seemed to us that morning as we stood by the ice encrusted rigging and watched the early sun light up the mountains of this fabulous island. In the half light we could see fifty or sixty miles of glaciers, snowfields, and now at their crest tinged brilliant orange, high peaks, all but one unclimbed, all but a few unnamed, rising seemingly straight out of the ice mottled sea.

South Georgia, not really so very far south, but, unlike Cape Horn in the same latitude, lying within the Antarctic Convergence is an important centre for whaling and sealing. Sheltered in the deep inlets of uJe north coast are three whaling stations. One might expect that on an island where there is so much activity there would be little work left for explorers. But of the hinterland, distant only a few miles from these isolated pockets of industry, nothing was known, even the coastline was only incompletely and imperfectly charted.

Duncan Carse had led two previous expeditions to South Georgia and in spite of a climate as difficult as any in the world, ten months’ sledging had been sufficient to map two-thirds of the island. Our task was to complete the job.

We were an eight man party, Duncan Carse being the leader. Second in command was Dr. Keith Warburton. We had two surveyors, Capt. Tony Bomford and Stan Paterson. Louis Baume, Tom Price and John Cunningham reinforced the climbing element. I was the photographer.

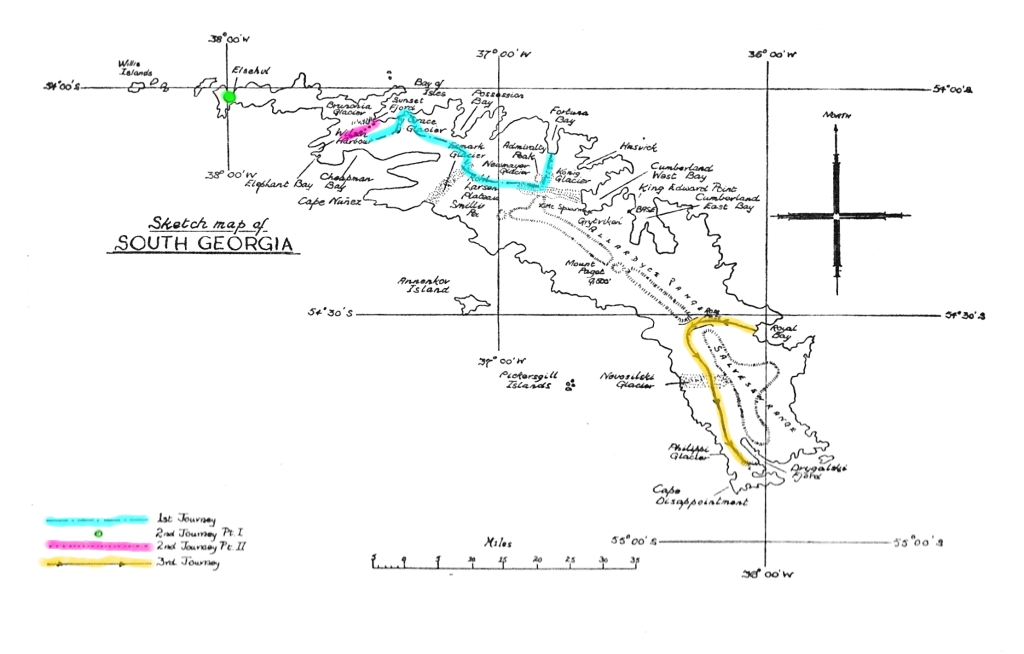

Immediately after my return we departed on the first 60 day journey. After a boisterous passage we were landed with our three sledges and 3,000 lbs. of stores at Fortuna Bay. We were to travel by a known route to the Kohl-Larsen Plateau, an elevated snowfield in the centre of the island and just to the north-west of the main Allardyce Range. From the Plateau we hoped to discover and follow a route more or less along the central watershed of the island until a junction could be made with the country already surveyed at the head of the Brunonia Glacier.

Sledges were manhauled, an exhausting and painfully slow method of travel. But in South Georgia where distances are not great, where much time must be spent at one camp for purposes of reconnaissance and survey, and more time spent waiting for good weather, the use of dogs would hardly be economical.

The first day of travel we had gained from our camp on the beach little over a mile in distance and perhaps 500 feet in height. Fortunately on few days was our effort so little rewarded. Once established on the glacier and on a surface hard frozen we had made better progress, sometimes putting a distance of twelve miles between camps. But such days were exceptional. Rarely were we on a level surface and when mounting to a col sledges had to be relayed. If in an hour one made one a and half miles it was good travelling, and on unbroken snowfields and glaciers interminably long, in a landscape to which nothing gave scale, sledge hauling became not a little tedious and the order to make camp most welcome.

We sledged up the Konig and the Neumeyer Glaciers. On the latter we camped below the 4,000 foot face of Mt. Spaarman, a face no less steep and almost as high as the Brenva Face of Mont Blanc. It was impressive country.

Ten days after landing at Fortuna Bay we established Camp VIII on the Kohl-Larsen Plateau where the work of exploration and survey was to begin. More than anywhere else the landscape here had a Polar aspect. It was an extensive and elevated snowfield surrounded on all sides by mountains icy and austere. We were camped on the plateau a week and on all but one day the weather was perfect, cold indeed, but Alpine in character, brilliant days of sun above an unbroken sea of cloud. It was a fine setting for the opening scenes of the Expedition’s work, but later we were to see it in another mood, for the Kohl-Larsen Plateau was also the stage on which was played the dramatic close of the enterprise.

We took full advantage of the kindly weather. Every morning we were called at 3.0 a.m. and after a breakfast of porridge and cocoa, cooked and eaten by candlelight, we set out on skis in parties of two or three, either heavily laden with theodolite and tripod to a survey station or on a reconnaissance with only a light rucksack. Every day first ascents were made and every day, from peak or col, we viewed country unseen before.

The mountains were not high and perforce for survey purpose, we selected for ascent the lower and least difficult peaks. Mount Paget, the highest peak in the island, is only 9,500 feet, and there was little that exceeded 6,000 feet in height that we could see from the Plateau. But the worth of mountains is not measured in feet. These peaks had the form and individuality of the best in the Alps, and if the climb of an Alpine peak is measured from the hut, they had the height too. But they are not to be climbed in the same slightly casual fashion of an Alpine peak. Many would call for the greatest mountaineering skill, not a few might prove, if not unchmbable, certainly unjustifiable. These southern mountains carry in summer a winter garb where ice hangs at an impossible angle, and no one can overestimate the severity and danger of the weather in South Georgia. Where there is a greater cold to consider and frequent storms, unheralded and prolonged, liable to come with dramatic suddenness from any direction, where winds come in gusts of exceptional force and may blow without respite for many days, then no margin of safety can be wide enough and the line of retreat never too secure.

Had Stan Paterson worn his goggles when using the theodolite we should not have climbed Spaarman. But he did not do so and when the surveying from the plateau was complete, Stan, his eyes hidden behind plastered goggles, was lying in the tent in the agony of snowblindness. Baume stayed behind to minister to his needs while the rest of us moved camp seven miles to the west. In the evening Keith Warburton and I skied back to the patient.

We returned not in our sledge tracks but on a route more direct and on a glacier unknown. We skied by peaks like fancy cakes all icing sugar and whipped cream, over miles of level snowfield where distance lost all meaning, to our col, reached steeply at the edge of a giant windscoop guarding a slender rock tower rich brown in the evening light. Far below were the two tiny dots of our camp and rising majestically beyond, Mount Spaarman. Now with no surveying we had hopes of gaining its top and so making the first major ascent.

It blew hard the next day, but the day following was all for which we could have wished. Travelling in a slight arc to avoid a section heavily crevassed we skied to the foot of a couloir. To our right, separated from us by a rock ridge and another arm of the snowfield was the peak the surveyors called ‘ Dimple.’ Cunningham, Baume and I had earlier made the first ascent as amateur surveyors, taking with us the lightweight theodolite. We had not been able to take the instrument very far : the ridge was too narrow to set up and the summit itself, gained by a steep slope of dangerous snow, proved to be a cornice of the utmost delicacy overhanging on its far side an appalling void, and barely safe as a restricted stance for one man.

The ascent of Spaarman presented no great difficulties : a couloir followed by a long undulating ridge led us to the summit. But had we reached the top ? Beyond was a second summit, perhaps no higher—we hoped not as high—but separated from us by a deep cleft and an arete narrow, twisted and tortuous. It was really a rock arete, guarded by many gendarmes but clothed in ice so thick that nothing of its structure could be seen. From its base rose abruptly a 200 foot tower encrusted in pillars of vertical ice. If that is the true summit then Spaarman will long remain unclimbed.

The next day we joined the others at Camp IX and settled down to three days of blizzard. We were to experience weather more typical of South Georgia. Rarely now did we enjoy two consecutive days of fine weather and almost half our time was to be spent lying up in conditions that made either travel or survey impossible. Yet we travelled in all but the worst weather and seized every opportunity of going to a survey station. Often before the day had shown its hand, we had dug out theodolite and tripod, un-lashed rope and iceaxes and set off on skis for some neighbouring peak, hurrying to beat the onset of cloud, only a few hours later to return disappointed, anxiously searching for tracks fast disappearing in a fury of wind and snow. Often on a morning full of promise, we broke camp, only shortly afterwards to be forced to halt, and after struggling in the rising wind with billowing tents, again seek refuge in our fabric homes.

On October 27th we were travelling across the narrow isthmus between King Haakon Bay and Possession Bay. It was into the former that Shackleton had brought the James Caird after his perilous open boat journey from Elephant Island and he must have crossed this isthmus. By a strange accident we were to follow in reverse his route more precisely than we had intended.

We were travelling in low mist. At the foot of a steep slope we left the three sledges and skied up into the sun. Directly ahead was the col for which we were aiming. We returned and taking one sledge at a time laboriously hauled two of them up on to the sunny snowfield. We would make camp here and there was time enough left for a climb. We ran down for the other sledge.

It was some time before we realised what had happened. We came to the bottom of the slope and were again in the cloud. Without thinking we walked past the area of trampled snow and chocolate wrappings peering forward for the sledge. It was not there. Anxiously we hurried forward ; then we saw them. Two parallel tracks veering away from the others, disappearing into the mist down the glacier, lonely sledge tracks unaccompanied by ski or foot marks. Somehow set in motion, the sledge had gone and with it two of our tents, all our Primus stoves and all but one of our sleeping bags. The glacier, the same one up which Shackleton had toiled, descended to a maze of crevasses and ended abruptly in an ice cliff falling into the sea. It seemed that the sledge and its load must be a total loss and with its loss, not only was there a situation fraught with hazard and hardship, but we were face’d with the effectual end of the expedition.

Such were our thoughts as we despondently followed the tracks, as sad and gloomy now with the bleak prospects as a short time ago we had been gay with the promise of a good climb. Not until we had dropped below the mist did we have a glimmer of hope. The sledge by a miracle had kept to the side of the glacier. There were crevasses here too, but fewer in number and smaller. For about three miles we followed the tracks until they led to a slope, more of ice than snow, and very steep. At the bottom was the moraine and there, mounted high on its side, its load widely scattered, was the sledge. It rested but a few yards from the site of Shackleton’s “Peggotty Camp.”

I did not expect always to enjoy sledging any more than I expect to enjoy every moment of an Alpine holiday or any moment of a very hard rock climb. I was pleasantly surprised. There was sometimes a degree of discomfort, but no hardship. There were periods too of monotony, but the scenery, when we could see it, was full of variety and the weather, more varied than the scenery, gave not only an element of uncertainty to any day, but the contrast between complete relaxation and idleness and hectic and prolonged endeavour.

Even in bad weather our camps were for the most part comfortable. The tents were effectively sealed against wind and snow and our only enemy was condensation. Irritating rather than uncomfortable were lying-up days in high wind when the flapping fabric caused internal draughts that made us forget our books and unwritten diary and burrow deep into our bags. Such was the noise that conversation was impossible and lighting the Primus was wasteful of matches, Meta and temper.

We lived in sturdy two man tents whose simply laid out interior became through long days of lying up the scene most familiar to our eyes. Once installed in our sleeping bags we were not in the least cramped and without undue discomfort we could devote the hours of enforced leisure to reading and writing. Thus ensconced and protected we travelled far from the stormy snowfields of South Georgia immersed in the great literary masters. And so the days passed pleasantly by.

But there came times when our peace was broken and our little sanctuary of learned and lofty thought was invaded by the insidious intrusion of snow trespassing upon our treasured space. I do not mean that it entered the tent I mean the snow outside that fell and drifted and built itself up in banks around us, mounting ever higher and consolidating in solid walls so that the sides of the tent collapsed and the ridge sagged.

This invasion was never deeper and more prolonged than at Camp XII. For seven days it snowed almost without ceasing. The level of the snow rose until it was nearly four feet above the level of the ground sheet and close to the apex of the forward poles—the space inside grew limited. The centre of the tents hung down under its increasing load, dividing the tent into two compartments. With outstretched legs pinned down, restricted of movement, in hollows moulded to their shape, we sat, huddled close together in a small triangle of space. We were free now from the hammering drift and the flapping fabric, inside the tent it was strangely quiet. The wind could do its worst. We felt safe and snug in our little hole.

High mountain ridges with unsledgeable cols cut across our route. One such ridge took tjs five days to turn and we did so only by descending to the beach. But the warmth and colour of the seashore was a refreshing change from the barren, hostile wastes in which we had so long been living. We killed and flensed a young seal whose meat gave a welcome change of diet, and collected a store of red yolked penguin eggs, Our camp there was a pleasant place, noisy with the cry of the tern and the Antarctic skua.

Three days later we were fully returned to the turmoil of wind and drift. We made Camp XVIII on the lee side of a steep col at the head of the Glacier. It was a bad site. Our tents had so far stood well up to the threat of the wind, but here we were to be exposed not only to a wind uncommonly strong, but a wind that came down from the col above in gusts of unequalled force. We estimated dieir velocity at no knots.

The hurricane blew for sixty hours. From the first we reahsed the danger. There was little sleep for anyone ; the noise, the hammering of the drift and the constant lashing of frenzied fabric might not have prevented sleep—we were familiar with such disturbance—but anxiety was now added to our discomfort and we felt compelled to brace the poles with our backs and with outstretched arms ease the tortured cloth.

In the early hours of the second morning Duncan Carse’s tent was ripped open and a few hours later a second tent became untenable. With both surviving tents now sheltering their maximum number we were without a margin of safety. In preparation for an emergency move we sat booted and in wind-proofs, our sleeping bags rolled into rucksacks. And so we sat through the second day and the third night and the worst hours of the blizzard, cold and cramped, fearful for the fate of our tent ; four silent shivering shapes, vaguely outlined in the occasional glow of a pipe. There was a strange macabre atmosphere about the scene.

But by first light we could discern a reduction in the frequency of the gusts. By 8.0 a.m. it had so far lessened that we were able to leave the tents and we moved down the glacier away from this malevolent spot. We repaired the tents, struggled into the wet sleeping bags and fell into a long sleep of exhaustion.

Now with two tents weakened and time running short we modified our plans. Only four men went forward to complete the junction with the known country to the north-west. But crossing the col, an arduous backpack, was a task in which we all shared. Of course by the time all the loads were up it was again snowing and blowing. Quickly we wished the others luck, ran down to the glacier and on skis raced along our fast disappearing tracks.

The next few days provided the wettest camping I remember. This was only partly due to the fact that Louis Baume had spilled on to my sleeping bag a full pot of Pemmican. The greatest measure of its cause was the profoundly disturbing practice which changing winds reluctantly forced upon us, of swinging tents. Our tents were wedge shaped to point tail to wind. In view of recent experience we could afford to take no risk. When the wind changed so had we to change the direction of our tents.

When we returned from the backpack the wind had changed to the north and for forty minutes we struggled with tents perversely ungovernable before we could claim their shelter. Twice the next day we repeated the performance. It was devilishly annoying. Cursing we struggled into wet windproofs and crawled out into a torrent of wind and drift. Sledge boxes were passed out. Other figures emerged, bent against the wind. Only one man could be spared for digging ; the rest of us hung on to the tent. Sledge boxes were put in new positions ready to place on the flap. Holding tightly to each pole and to the sides, ready to fall on to the billowing cloth should the wind take control we shuffled round pivoting on one tail guy left embedded. When both tents were again secure, bringing with us much snow, but too cold to bother, we crawled thankfully back into the chaos inside. After a few hours we were out again doing the same thing.

Ten days later the two parties were again reunited and we started the long trek home. Space does not permit me to give details of these events, of the weekend of lavish hospitality we enjoyed as guests of the Norwegian Whaling Station on our return, or anything but the briefest account of our other journeys.

On December 13 th two four-man parties were landed at Sunset Fjord and at Elsehul. Carse, Paterson, Price and I were on the latter.

Elsehul at the extreme north-west end of the island enjoys a climate less severe than the remainder of the island. There was little snow, much vegetation and an abundance of fearless wild life. For four weeks we camped close to the shore in a situation and scenery that reminded me much of Loch Scavaig. It was a static camp and although the weather permitted only limited climbing and survey we thoroughly enjoyed living in this nature lover’s paradise.

We were sledging again on our third journey. Landed at Royal Bay we crossed the Ross Pass and entered the unexplored country to the south of the Salvesen Range. An excellent sledging route was found rising at one point to over 4,000 feet it took us through the finest country we had yet seen. The surveying went well but unfortunately bad weather and lack of time permitted only one major ascent, an unnamed peak of 7,200 feet.

On February 22nd we made Camp XIV at the head of the Philippi Glacier. We were only one day’s march from Drygalski Fjord where we were to be picked up. But here wc suffered a setback. We were entombed in our tents for eight days while it blew almost without interruption at hurricane force. Fortunately the wind was constant and there were none of the dangerous gusts that were so damaging on the Grace Glacier, but the abrading action of the icy drift on the suffering ventile was such as almost to wear through sections of the fabric. It had been our intention to be transported direct to a landing on the south coast but now we must return to base for repairs.

On March 1st we sledged down the glacier. It was a perfect day. The mountains fell in great cliffs of rock or ice nearly 8,000 feet to the sea. It must be amongst the finest coastal scenery in the world. Far below drifting among the ice debris in the black waters of Drygalski Fjord, patiently waiting for our appearance, was the sealer Diaz.

The last journey was quite abortive. Unable now to land on the south coast we were to travel again to the Kohl-Larsen Plateau where by crossing a high col we could reach the glaciers and snowfields that descend to the south of the main Allardyce Range. It was our earnest hope that we should be able to complete the season’s work by making an attack on Mount Paget. But we never reached the unknown country and we got no nearer to Paget than we had been before. Yet for five of us there was to be an experience that at least in retrospect, we should not have liked to miss.

There was now little snow cover on the lower glacier, the crevasses were open and after landing in West Cumberland Bay we had three days of arduous backpacking before we were established on sledgeable terrain. Camp VI was pitched on the Kohl-Larsen Plateau. We were on familiar ground.

March 14th dawned fine. We were out of tents by first light and while three set off for a trig, station, Carse, Warburton, Baume, Cunriingham and I moved camp across the Plateau. Soon after midday the wind freshened. A blanket of cloud was already sweeping up from the Neumeyer Glacier and filling up the Plateau, although as yet we were above it. We deemed it wiser to halt and pitch camp.

At 3.0 p.m. the others had not returned. We felt some anxiety, our tracks were rapidly drifting over. Accordingly we decided to go out and walk in line abreast on the line of their return. And so we left the tents, not imagining we should be away for long and neglecting to take with us those items of equipment essential to our safety.

With Carse in the centre of the line, holding the compass we staggered forward half against the wind. After thirty minutes we halted and waited, all the time the weather worsening and our line narrowing. It was evident we must go back while we still could. No longer now was the high ridge behind our camp visible.

Carefully we walked back on the reciprocal course, but a course in this wind was not easy to hold. After twenty minutes it was obvious we had overshot the tents. We turned and punched against the wind, but we could not keep it up for long. Eyes froze up and lungs filled with fine powder snow so that we gasped for breath. Backwards and forwards we went for two hours searching in a zig-zag pattern.

Short of finding camp our only safety lay to the north, back down the Neumeyer Glacier, but that was against the wind and was not to be thought of. Downwind was unexplored country and crevassed glaciers falling steeply from the Plateau. We had

no skis, no ice-axes, no rope, nothing to make travel safe. We had no food or spare clothing and we had left but one hour of daylight. The position was not a pleasant one.

Then Cunningham put a foot through into a crevasse. We peered down into black emptiness, but at one end it was shallow and friendly. A steep slope led to a platform beyond which the crevasse opened out and plunged into greater depths. Immensely relieved we sought its shelter. It was quiet and peaceful, our voices absorbed by the icy walls were hushed and the wind could only be heard now like the faint rumbling of distant artillery. We were lucky to find this refuge and our spirits were high.

We were for the moment safe, but there was little comfort. For ten hours we stood and shivered, vigorously stamping our feet, too cold to relax, not daring to sleep. We had little reason to believe dawn would bring relief. The recent eight day blizzard was vividly on our minds. When grey light filtered through the hole above and we looked anxiously out we found no visibility and the wind still blew with fearful force. But there was one vital change ; it blew now from the south.

We were worried for the others’ safety. They were better equipped for it but presumably, they too, were suffering similarly. Our physical condition was fast deteriorating and after a second night there might be little help that we could offer. It was decided then to get out and to risk the fight back to the coast and the safety of a Whaling Station. We knew the compass bearings and the wind would be at our backs.

Outside it seemed so impossible we wondered for the moment the wisdom of our move. But action was better than this soul destroying inactivity which so insidiously sapped our strength. We made rapid progress but by late morning we were again in trouble. Off course on the slopes of Spaarman which fall steeply on to the Neumeyer Glacier we had wandered into a mass of large crevasses. Gingerly we crawled over them where bridges could be found until the slope became too steep. Back we went, the worst moments of the whole episode, crawling, blinded and choked by drift, seeing only occasionally the feet of the man in front, fearful lest the slender link between us was severed. We could only struggle thus for a few minutes and when we found a shallow crevasse we got into it, resigned now to a second night.

But it would hold only three of the party and unexpectedly while searching for alternative shelter a way down was found.

Our hearts were immeasurably lightened. Only one further peril remained ; the maze of narrow but deep and thinly bridged crevasses that lay four miles down the glacier. We crossed them in a line diagonal to the fissures with arms tightly linked. At almost every step one or the other of us would go through. Only once did the chain break. Cunningham disappeared altogether, happily to wedge unhurt some twenty feet down. He was able to climb out.

That was the last of our trials. Only straightforward walking separated us from the food, comfort and safety of Husvick into which after thirty-six hours of almost continual effort the five exhausted explorers thankfully staggered.

There is little more to tell. While we visited base to equip ourselves for a return to the Plateau, Carse and Warburton, thanks to the co-operation of the Captain and Flying personnel of the whaling factory ship Southern Venturer, made a reconnaissance by helicopter. Coming down the glacier, hauling two sledges, were the missing men. They had found the tents and had suffered nothing worse than anxiety.

So ended our six months of endeavour and a wealth of experience. Virtually our work was completed. Explorers and surveyors will find now South Georgia is a poor field for their efforts. But for die mountaineer the work has hardly begun.