Fairy Hole Cave — Weardale

by D. M. H. Jones

“The wettest, muddiest, vilest, most miserable cave it has ever been my misfortune to enter.” Such is a characteristic comment on Fairy Hole, and certainly a more ineptname than ” Fairy Hole” could never have been chosen. However this stream passage, running through a 67 foot bed of limestone, has a certain claim to fame if not to beauty. It is already the longest single passage in Britain, and its furthest depths still offer scope for further exploration. For those wanting an arduous day’s caving it stands, I am told, second only to Mossdale.

The cave lies in Weardale, between Eastgate and Westgate, on the south side of the valley. Its entrance at O.S. 1,150 ; grid reference 944374, is the smallest of several holes lying in a hollow thirty feet above the source of the Ludwell Burn. Local inhabitants apparently explored its lower reaches over 100 years ago, but since then its entrance has been partially blocked. An account of first excavations and explorations can be found in the Fell and Rock Journal No. 49, Vol. XVII, ” The Blind White Trout of Weardale” by D. H. Maling.

The cave is one long passage either in the stream or following its line. Off-shoots are small and with one or two exceptions run for no more than a few yards, yet it is surprising how many obstacles make route finding difficult and progress arduous. The entrance is a short belly crawl with a puddle for your stomach. It leads to an antechamber from which a 20 foot slide down a chimney brings you to the stream. After a few yards the passage opens into a chamber with a 14 foot waterfall at its end. I am not sure of the depth of the pool beneath this, (having so far managed to avoid falling in). An underwater ledge skirts the right side of the pool and so the wall is best hugged closely. You now have to reach the top of the waterfall. For the lazy and the confident the wall to its right may be climbed diagonally upwards and to the left. For the more energetic and those who fear a wetting there is a narrow passage leading upwards in the right wall of the chamber which, after suitable contortions, leads above the waterfall.

The water over the next section of passage is deep. You traverse ten feet above its murky depths on ample calcite ledges.

The walls are close together ; one hand can rest on each wall. Sometimes one walks on one side, sometimes on the other, sometimes one straddles. Odd obstacles disrupt the steady progress; a wide stride across a side passage, a five foot step up, a six foot drop down. The passage, as in the whole of its course, twists and bends but keeps its main direction. Two pools block progress ; pools with vertical walls disappearing into dark and deep looking water. These on closer acquaintance prove to be no more than knee deep. An enjoyable traverse on good stalagmite holds can be made round the left side of the first pool. This saves a vertical pull up on poor holds, made awkward by the vast weight of water in one’s clothes. The second pool can be traversed on its right wall. But this is quite a delicate procedure and many, including myself, find it quicker to submit to ordeal by water. Indeed from this point it is possible to travel the whole time in the water. This is quicker and easier, but less interesting, and, needless to say, wetter. The upper route, again on limestone ledges, may be followed for a further 70 yards, but as this point, 210 yards in, descent into the water can no longer be avoided. The early, cleaner, drier, and more interesting section of the cave is over.

The next section is a wade along the water passage, punctuated by numerous small rocks to trip over, and several large obstacles to climb over or duck under. The walls are a thick layer of mud which covers everyone from helmet to boots. It has an abrasive quality which wreaks havoc with ungloved hands. Only the hair remains really clean and dry, and offers a suitable surface on which to wipe muddy hands ! The water is sometimes ankle deep, usually knee deep, occasionally deeper. These levels refer to times when the stream is low. High stream levels, or saturated subsoil and threat of rain make long expeditions inadvisable. Rainfall causes a rapid rise in water level. In the lower part of the cave this will probably not be serious ; the wade out may be acutely uncomfortable but there is at least air to breathe and room to swim. Even the ” Duck ” further into the cave may be circumvented (by a route 10 feet upstream in the left wall). But water levels in the upper part of the cave show that the crawl passages may become completely filled with water. Even the Choir (a higher chamber) may be partially submerged, and attempts to camp in this region are most inadvisable.

At 470 yards in, there is an inscription scrawled on the left hand wall : “June 8, 1844, J. D. Muschamp ” with more names on the opposite wall. Thus far we presume the early explorers reached, and certainly the further reaches of the cave were quite impenetrated before the recent wave of exploration. At 650 yards in, you walk into the Boulder Chamber, 30 feet across, more or less circular and needless to say a mass of boulders.

The stream is reached again by slipping down through a small hole in the far left hand part of the chamber, a manoeuvre which entails squatting in the water for one brief but unpleasant moment. From here there lies ahead a long steady wade with few obstacles to interrupt progress. Such long wades seem terribly dull on the way in, but a great relief on the way out. For when you’re tired it is change that is unpleasant ; be it descent from dry rocks to cold water or the hauling of a wet body over awkwardly placed boulders. All that you desire is to be able to wade onwards monotonously, drinking only of dry bed or bacon and eggs. This long steady wade has one notable feature, a point where roof nearly touches water. Now there is a foot of air space ; first time through there was only six inches. It was a little unnerving to squat on one’s haunches, throw one’s head back, and with nose in air edge under the constriction. But the roof was only low for two feet ; the pleasure of watching one’s companions negotiating ” The Duck ” proved more than ample compensation.

This is a region in which it is common to see white trout— although they have been seen in most regions of the cave. Several inches long, and apparently blind, these fish are rare in Britain, and had not previously been caught ot studied closely. However, J. Newrick knocked one out with a detonator explosion, and managed to collect the stunned fish as it floated downstream. It was duly despatched (alive) to the British Museum.

From 1,300 yards a series of petty obstacles begin toobstruct the way ; awkward lumps of stone to climb over, a narrow squeeze round a rockfall, steps up, slides down, the odd deep pool. But deep pools in Fairy Hole just aren’t what they used to be. In ” the good old days ” a deep pool was arm-pit depth (or nearly) ! But time and sand have filled most of them up, and ” Ashworth’s Swim,” a pool originally thought to need swimming, but on third exploration, when someone fell into it, found to be only chest deep, is now completely silted up.

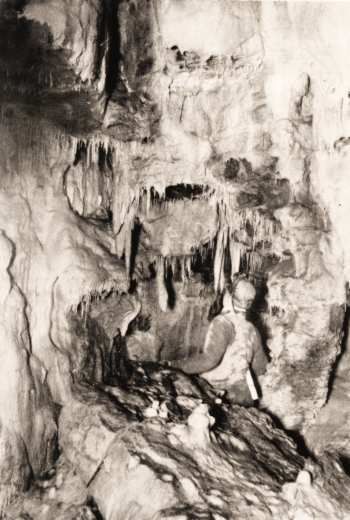

At 1,790 yards you reach the Vein chamber. Here the passage is completely blocked by boulders. This small chamber lies above these and you have to climb vertically upwards and squeeze through a hole to reach it. A small mineral vein crosses its low roof. From the roof hang the first large collection of straws to be found in Fairy Hole. Some are now broken off, others spoilt by mud ; nevertheless many remain and it is a pleasing sight.

Though there are several routes out of the Vein chamber only one is advisable. An upper passageway leads to the second Coral Gallery — now out of bounds in order to preserve these fine formations. The first Coral Gallery lies further downstream, a little way before Ashworth’s swim. In spite of frequent visits to the Vein chamber, I still find myself about to crawl along the wrong passage or to descend the wrong slope. It is quite surprising how often one manages to lose one’s way in a cave where by and large there is only one route. For instance the route back through the Duck is not the apex of the pool of water but slightly back along the right hand wall. One duck is bad enough ; to fumble around trying several in succession is no fun. And so, by trial and perhaps error, your reach the water again and continue wading upstream. After a while a choice of two narrow fissures presents itself — both mercifully widened by the passage of many bodies. Then more wading, past “Corbel’s Waders Pool” — once deep, now shallower ; so called because the French speleologist Jean Corbel came to grief in enormous waders in this pool. These superb objects had kept out water in many continental caves, in Fairy Hole they met their Waterloo! Forty yards on another rockfall necessitates a vertical climb upwards between two massive boulders, followed by a slide down a pleasantly nobbly slab. More wading still, round corners where the water reaches higher and higher for longer and longer — groin, then middle, but when the stream is low, no deeper. Various small unremarkable obstacles punctuate this watery journey, then at 2,425 yards there is again a choice of two narrow parallel fissures. At the downstream end of this a sizable tributary stream joins the main passage. This becomes comparatively small after 100 yards, but with more exploration and with digging and blasting might well provide a short cut into the cave.

At 2,490 yards a large rockfall completely blocks the passage. You must climb up a chimney which lies between the face of the rockfall and the roof from which it has been separated. You soon peer into a sandy chamber above the fall, but it is not so easy to squeeze your body over the lip and into this chamber, indeed unless you adopt the correct prodecure you are apt to writhe and struggle there for some time. The secret is to keep in the farthest corner of the chimney until as high as possible, and only then to traverse right to the widest point of the chimney. Grave Chamber is small and sandy and pleasant, and it needs to be. You cross to the far right hand corner of the chamber on to a slab, and roll off its edge into a 6 foot long grave. Then follows an extremely tight stomach crawl. By dint of manipulating one shoulder under a prominent bulge, by kicking and squirming, by disentangling the rim of your helmet from one knob and your torch wire from another, you attain a comparatively spacious crawl. This ends in a doorway looking through into another boulder chamber. Across this chamber and down to the stream again—this is the last stretch of stream wading for some time. After another 210 yards, 2,735 yards into the cave, one reaches the Choir.

The Choir is perhaps the most interesting chamber in the cave. It is long and low, and large areas of its roof are covered with delicate straws. Its floor is almost completely covered with sand which gives it a soft friendly character. Along one side a row of stalagmites stick upwards through the sand like surpliced choirboys in a pew. An excellent spot for lunch.

A short crawl through a passage which at one time contained numerous straws, leads to the Vestry — another boulder chamber. At its far side the stream passage continues, but its roof soon descends to water level and further progress is blocked. Fortunately an upper passage leaves the Vestry above the stream passage. This, the Via Dolorosa, is sandy and dry, and guaranteed to warm any person cold from water wading. Progress varies from “monkey run” to “leopard crawl.” Sometimes the floor is smooth, but more often strewn with boulders which manage to tear to shreds all but the strongest boiler suits. An oxbow loops off to the left, both entrances of which are more prominent than the main passage. At the furthermost entrance boulders reduce the route onwards to a letter-box slit. The original explorers swung back down this oxbow and discovered a fine new chamber which turned out to be the Vestry ! After the letter-box slit the crawl becomes particularly devilish ; Easegill’s “Poetic Justice” is “prose” by comparison. After 150 yards of total crawling a small chamber gives access to the stream again. But another syphon blocks progress and the upper passage has to be followed. This chamber, 2,950 yards into the cave, is the furthest point so far surveyed. Fifty yards more crawling brings you to another fall blocking the passage. At this point the passage is only 2-4 feet wide, but the exploring party managed to spend two hours finding a route through. This was due to three levels of passages. (1) The passage you have just come along ; (2) a sandy crawl ten feet lower down ; (3) the stream six feet below this. The key to the problem lies in the sandy crawl which you reach by a simple climb down a chimney. In a forward direction it is narrow and ends in an impassable boulder block. However, just before reaching this a very unlikely upward sloping crawl strikes sharply to the right. A sharp left bend and a few more feet bring one through the fall into a wider passage. The same point can be reached by a squirm through the boulders in the floor of the upper passage, a route not to be recommended. On no account follow the much more hopeful looking end of the crawl passage going back downstream.

A twenty yard stoop brings one to the Sarcophagus. This is so far the largest chamber in the cave, It has the length of the Choir, the height (at least) of the Vestry, and is wider than anything else. The stream winds its way beneath the boulder floor—accessible at two points in the cavern. The chamber is shaped like an H. One enters by the bottom right limb ; the stream passage leaves by the bottom left limb. In the top right limb a sandy funnel leads up to a crawl passage. The top left limb is the longest, its boulder floor mounting up towards the roof. Near its apex there is a very beautiful, very concentrated group of straws — worthy of the Upper reaches of Lancaster Hole. Beyond this, a small opening leads down into a spacious sandy passage which soon descends further to the stream. The stream passage here is most accommodating ; wide, no deep pools, no obstacles, you forge ahead at great speed. For four hundred yards you maintain progress which would soon bring you to the upper limit of the cave, but alas, this progress is stopped quite suddenly ; the roof sweeps down to water level — to drought water level.

So far, this is the furthest point reached in the cave, and indeed it has only been examined once. Fresh eyes may detect fresh lines of attack, but at the moment the picture is not cheerful. To the right of the syphon, at waist level a hole, which must be one of the muddiest in a very muddy cave, leads to a channel of water about 2\ feet wide. The water depth is uncertain — by sounding it seemed about eight feet. By straddling along crumbling mud ledges it is possible to look beyond a dilation to a point where die channel becomes a narrow slit. This reaches its maximum width of eighteen inches for only one foot above water level. A strong draught is present and may come from a fissure above one’s head — a fissure which would not be easy to climb. No other signs of a route over or under the syphon have been seen.

And what of the crawl passage leading from the right limb of the Sarcophagus. It was hoped that it might provide a more arduous but surer route to the far side of the syphon. It too is blocked — by a rockfall — about three hundred yards from the cavern. Nor would it seem to follow the line of the cave at all. According to one hurried series of compass readings, it runs at right angles to, then doubles back on, the line of the cave. Numerous oxbows provide further scope for exploration, but don’t seem very hopeful. So another subsidiary passage must be found, or else the syphon or channel braved. Epic swims are not popular with five hours hard caving both before and after.

This description gives some idea of the cave, considered as one long continuous trip. It does not properly portray the cave as it actually unfolded itself to its explorers—in little bits, and to parties of different size, strength and composition, chipping away fresh sections of the unknown passage :—

The Northumberland Mountaineering Club excavating the entrance.

Newrick and Maling descending to the stream and reaching the first pool.

Chapman, Butcher and Conn exploring the first and second pools, discovering their depth by jumping in, and pushing onwards towards the Boulder Chamber.

A large rambling expedition, a few of whom reached the Boulder Chamber : the first hesitant explorations beyond—the Chapmans and Jones turned back by the first pool of any depth at all.

Fawcett, Ridley and Jones covering the long, easy plod in water, negotiating the Duck, and being turned back by the rockfall beyond.

Newrick and Myers negotiating this rockfall and exploring the first Coral Gallery in the roof beyond, while Riley and1 Ashworth pressed on below over numerous small obstacles to Ashworth’s Swim.

Newrick, Heys and Myers crossing Ashworth’s Swim, reaching the Vein Chamber, and exploring the second Coral Gallery above the stream beyond.

Fawcett and Jones squeezing through the first fissure, floating across Corbel’s Waders Pool (then unnamed) on a rapidly leaking lilo and pushing onwards to a point just short of Grave Chamber.

Newrick, Chapman and Jones enjoying perhaps the most exciting day’s exploration forcing a route through the Grave Chamber and tight crawl, and discovering the Choir and Vestry.

Railton, Little, Corbel and Newrick discovering the syphon beyond, digging to lower the water level, then exploring the beginning of the Via Dolorosa.

Newrick, Keegan, Huntrod and Jones exploring the next section of the Via Dolorosa, taking a wrong turning and rediscovering the Vestry.

C. Brindle, Holden, Bradshaw and Myers finding the way on through the narrowest part of the crawl which Bradshaw pushed as far as the descent to the stream.

Chapman and Jones adding 70 yards the following day.

Sherratt, Fawcett and Jones worming their way through the four foot wide rockfall, at one point all three becoming stuck in different tight squeezes simultaneously, and being rewarded by the Sarcophagus.

Sherratt, Belshaw and Jones stopped short by the syphon, sounding the channel with an ice-pick on the end of a nylon rope, and having equal lack of success in the upper sandy passage.

And parallel with these explorations the survey work carried out by Myers, Heys and Newrick.

So much for Fairy Hole from its downstream end. The water which causes so much discomfort to the caver disappears underground 2 miles 360 yards away from its point of emergence, at grid reference 926343. Of this distance 1 mile 600 yards as the crow flies has already been covered below ground. Several attempts have been made to force an entrance in this upper region, but so far all have met with failure. By diverting the stream, Newrick and Hilton were able to descend along its course for a few yards. It soon became an impassable bedding plane. A lead mine, unworked for 100 years, enters the hillside 500 yards away. It is believed that its workings sweep across the line of the cave. Two days’ digging forced an entrance. Driven in shale, with a limestone roof, rotten pit props, and a major rockfall one hundred yards in, this route is best left alone. A vertical fissure close to the sink has been enlarged by blasting and leads to a horizontal fissure which needs a similar treatment. Again it is doubtful whether even this would force an entrance.

So we are left with several “possibles” but no “probables.” It is unthinkable that with such a large part of the route explored, it should not eventually be forced through in its entirety. The stream passage at the furthest point is still of large size, and should remain passable for a long way when once the syphon is negotiated. Indeed it has been suggested that since the large chambers are so deep in the cave, the original stream must have entered the ground much further away, and once we reach the present water inlet a dry cave will stretch onwards!

The geological and natural history side of Fairy Hole, together with a detailed account of the exploratory journeys, is being covered by J. Myers in an article to be published in the Northern Pennine Club Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1. In the same Journal, J. Newrick is writing a full account of the white trout. Here I should like to acknowledge the debt I owe to both these for their help in compiling this article.

Permission for entry to the cave, which is on private property, should be obtained from the President of the Durham Cave Club, J. A. Newrick, High Whitestones, Ireshopeburn, via Bishop Auckland, and will normally be witheld during lambing time.