We Can’t All Be Explorers, But —

by W. Lacy

Standing on the deck of the “Erling Jarl” I glided across the Arctic Circle, but to all appearances I might have been within 20 miles of Glasgow. As a very young boy I had read of Nansen, Scott and Amundsen and had dreamt that one day I might visit the Arctic too. Forty years later that oft repeated dream had come true. But not on an expedition—-just a dash along the route real explorers had taken and back home within 30 days. Within an hour of crossing the line, however, the Svartisen glacier could be seen glistening in the morning sunlight, and shortly afterwards the ship stopped at Gronoy (Green Island). This is a surprising haven of peace and beauty amongst the seawashed rocks of the Norwegian coastline. The Svartisen is the largest glacier in Europe and produces a local area of high pressure, which in turn creates a belt of good weather, tall trees, long hours of summer sun, and a fine centre for walking and climbing amongst the neighbouring rocks and more distant icefield.

Midnight found me at Svolvaer in the Lofoten Islands. There I saw cod hanging out to dry, rock climbs starting from the harbourside, and a pale moon shining over the jagged peaks, houses, sheds, boats, and over all a strange peace in the reflected light of the midnight sun.

We then went oii through winding fjords to the Vestmann Islands and back to the coast of Norway and Tromso. For 130 years this town has been known as the Capital of the Arctic — 70 degrees North latitude with a population of 11,000, all busily engaged with ships, fish, seal hunting and furs. I stayed here a short while with Karl Lindrupsen, the Engineer Director of the Arctic Broadcasting Station. Being summer, he was not living in his house in the town but out in his cabin at the other side of the island. It was a peaceful yet fascinating time. A vase of antirrhinums was on the dining table and in my sleeping hut wallflowers were in ajar beside my bed — Spring and Midsummer together. At midnight Karl would say “Come, let’s go fishing” and we would go out in the motor boat. The tide would be running so fast in the middle of the fjord that it sounded like a rushing stream. Across on the other side lay the wreck of the Tirpitz. Back we came, wet and tired, and went to bed under a polar bear skin. There was a model farm on the island, but the only person I saw working it was a young pretty girl wearing only gum boots and a bikini, hoeing cabbages. Three thousand mink were squealing on an adjoining fur farm. Whilst walking in the town I met a Lapp and his wife in their best Sunday clothes, shopping. Later I was attracted to the quayside by most peculiar cries, and I found a sealer had just come in from the East Ice with 12 young polar bears aboard, three to six months old. The mother bears had been shot for their skins, and if the young ones had not been caught they would have died, as they stay with their mothers until two years old.

The Northern Lights Observatory is at Tromso. The Aurora Borealis occurs chiefly in that belt of the heavens between Tromso and Spitzbergen. The people of Spitzbergen strangely enough look south to see them.

I joined the ” Lyngen,” a small steamer which sails between Tromso and Spitzbergen. As we cast off, an old man was standing on the quay, waving and wishing us well, Helmar Hansen, Amundsen’s old dog driver, one of the few men alive who have stood both at the North and South Poles. In the Town Square behind, Amundsen, carved in granite, was pointing the way ahead. Very soon, the tail end of an Arctic gale was making life uneasy and not until we were in the lee of Bear Island did things become comfortable again. There we ran in towards the coast, stopped the engines, threw hand lines overboard and took on a supply of fish for the voyage. The line no sooner touched bottom than one began to haul in again. No art, just hard work with line cutting into the hand with the weight of the cod. It was between Bear Island and Spitzbergen that Amundsen was lost on his search by plane for General Nobile. Sharing the cabin with me was a Norwegian Meteorological Inspector who was paying an annual visit to the lonely posts set up along the coast of Spitzbergen. After a visit to one of these, he returned very annoyed, as he found that during a particular spell of bad weather, one of the men had failed to turn out to take the recordings, thus breaking a 20 years’ chart.

The ship entered Ice Fjord, Spitzbergen, and then sailed in calm water to the Coaling Station in Advent Fjord. Here the coal from the mines is stored throughout the winter and shipped to Norway during the summer months. We then moved to the quayside of Longyearbyen — Longyear City — the capital of Spitzbergen, the home of the Governor, and where there are 1,000 miners, 100 women and 30 families. The main street is a rutted track which leads two miles up a valley, ending at the foot of the Longyear Glacier. Three mining camps are spread along the valley, each half a mile from the other in case of fire, especially in winter, when there is no water. Just prior to my visit an avalanche of mud and rocks had crashed through the men’s large canteen hut in the lower camp, so in case of such disaster each camp has to be capable of supporting the men from the other two. Apart from the mining engineers, most of the miners are recruited on an 18 months’ contract. During that time they reckon to save sufficient to return to Norway, buy a house and marry. Only few do a second spell.

After a most interesting scramble on the Longyear glacier, where I found some fine specimens of fossilised leaves on its moraine, and on the way down, I happened to meet the chief electrical engineer and he suggested a bottle of beer might be welcome. He occupied a flat in one of the newer blocks which was most pleasantly furnished in modern Scandinavian style.

Coal mines exist in other parts of Spitzbergen. Some are manned by Russians at Grumantbyen and other places.

As we sailed from Longyear, the Governor and his wife came down to see us off. At Kap Linne we dropped David Atkinson, a member of the Oxford University Arctic Expedition. He was going to rejoin his companions on Prins Karls Porland after visiting the doctor at Longyear.

The ship turned North up the coast until we reached King’s Bay where, at Ny-Alesund, is the most northerly settlement in the world ; a coal mine, miners, radio station, doctor, children, two cows, two ponies, a railway engine, arctic foxes in the wood pile and delightful alpine flowers. There is also a stone monument on which is carved

AMUNDSEN

DEITRICKSON

ELLSWORTH

FEUCHT OMDAL

RIISERLARSEN

31 Mai 1935

to mark the first but unsuccessful attempt to fly over the Pole by plane, and an airship mooring mast from which the Norge set out to reach the North Pole with Amundsen and General Nobile aboard one year later. All these are set within a circle of intense grandeur of mountains, and glaciers, with ice floes drifting slowly by under a brilliant sky ; truly a scene to be ever remembered.

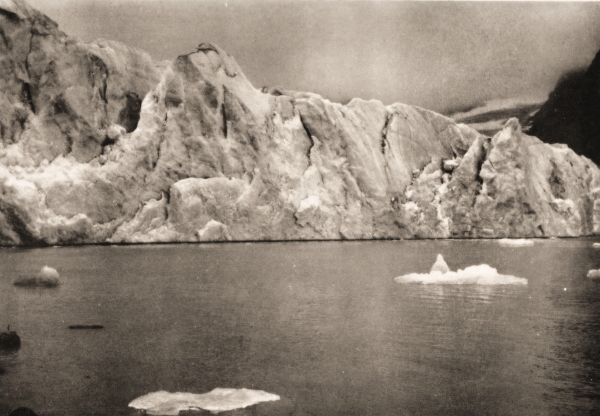

North again to Magdalena Bay surrounded by peaks and glaciers coming right down to the sea with their ice cliffs 100 to 300 feet high.

Onwards again to Dansköya and a safe anchorage between two islands at the north eastern corner of Spitzbergen. It was here in Smeerenburg Fjord that the Dutch built a whaling station in the seventeenth century which prospered until the middle of the eighteenth century, by which time all the whales were killed, 60,000 having been caught. The station was deserted, all now remaining being the graves of those who had once dared to venture there and who had stayed too long.

But in 1897 Andrée, the Swedish scientist, with two friends came to this place, made a camp, inflated his balloon and set off for the Pole. Nothing more was heard of them until their bodies were found on Kvitoya in 1930. Walter Wellman, an American, followed and built a camp close by Andree’s, but his balloon for one reason or another never got away and Wellman lived to return. Piles of timber and old iron filings are stacked around. It was from these filings gas was made to inflate the balloon. Rummaging around, I found two horse shoes and brought them home as mementoes.

From this point, 80 degrees North latitude, 600 miles from the North Pole, the “Lyngen” had to turn south. Rolling in a heavy swell, black smoke belched from the funnel and, trailing behind us, mingled with the ice glint in the sky.

So we left this strange land of musk oxen, reindeer, polar bears, mountains up to 5,000 feet high, glaciers, birds and flowers, seals, fishermen, miners and trappers — a land of summer sun and polar night.

And so you see, we can’t all be explorers, but—